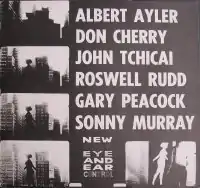

| New York Eye and Ear Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 1965 | |||

| Recorded | July 17, 1964 | |||

| Genre | Free jazz | |||

| Length | 43:19 | |||

| Label | ESP-Disk | |||

| Albert Ayler chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings | |

| The Rolling Stone Jazz Record Guide | |

New York Eye and Ear Control is an album of group improvisations recorded in July 1964 by an augmented version of Albert Ayler's group to provide the soundtrack for Michael Snow's film of the same name.[4]

Background

New York Eye and Ear Control came about when artist, musician, and filmmaker Michael Snow received a commission from a Toronto-based organization called Ten Centuries Concerts for a film employing jazz.[5] Snow had recently attended and enjoyed a concert by saxophonist Albert Ayler[5] (he recalled "I was completely knocked out"[6]), and had been making his studio on Chambers Street in lower Manhattan available to musicians such as Roswell Rudd, Archie Shepp, Paul Bley, and Milford Graves for rehearsals.[7] He decided to hire Ayler and his quartet (which at the time included trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Gary Peacock, and drummer Sunny Murray, and which had recently recorded the albums Prophecy and (without Cherry) Spiritual Unity), along with trombonist Rudd and saxophonist John Tchicai, to make a recording, stating that he "wanted to buy a half an hour of music."[5]

Snow recalled that he had certain stipulations going into the session: "I didn't want any previously played compositions, and I wanted it to be as much ensemble improvisations as could be with no solos."[5] He also stated: "As I was being involved with so-called free jazz, I was always surprised at how everybody was still bookending, as in all of previous jazz where you play a tune, play your variations, then play the tune again. I kept feeling that I didn't want that, and particularly what I had in mind for the film, I definitely didn't want it. I wanted it as pure free improvisation as I could get."[8] According to Snow, "They accepted and they performed this way... in my opinion, this is one reason for which the music is so great."[6] He later called the ensemble "one of the greatest jazz groups ever."[9] (In his 1966 essay "Around about New York Eye and Ear Control," Snow summarized his thoughts regarding the music: "Song form finally unusable, strict rhythm finally unusable in 'Jazz.' It goes 'ahead' where it has to... Surprise! Demand for Song and Dance so natural there can be 'new' Songs, 'new' Rhythm, 'new' Dances. A very pleasant surprise."[10])

The recording session took place on July 17, 1964 at the loft of poet Paul Haines, who was Snow's neighbor and who also set up and operated the recording equipment.[11][12] Roswell Rudd recalled that Snow "didn't say anything. He said just go ahead and play and when he got the time he needed, he took that and made a movie with it. In other words made the movie from an improvised jam session rather than make the movie and fit the soundtrack to it. He made a soundtrack and then went out and shot a movie. I don't know how many people have ever done that."[12] (The album liner notes confirm this, stating "The music was recorded prior to the production of the film."[13])

Snow's film uses the motif of what he called the "Walking Woman," a silhouette based on the image of Carla Bley.[14] Snow stated: "In my films I've tried to give the sound a more pure and equal position in relation to the picture."[6] "I was hoping for an uninterrupted stream of energy against which I was going to place the almost completely static shots of the two-dimensional Walking Woman figure, either negative or positive. The picture was edited with no reference to what sound episode might accompany it. It is an attempt to make a simultaneity of 'eye' with 'ear.' And the music was created to be a movie sound track, not to just be 'music.'"[15]

Regarding his choice of a title, Snow also said:

It's like the music is a particular kind of experience, and the film is something quite different that you see simultaneously. That's why the title, New York Eye and Ear Control: it was actually being able to hear the music and being able to see the picture without the music saying, This image is sad, or this image is happy — which is a way that movie music is always used. I really wanted it to be possible that you could hear them. So, they're very, very different. It's as if the image part of it is very classical and static. In fact, most of the motion is in the music actually. So, they're kind of counterpointing and being in their own worlds, but happening simultaneously.[16]

The film was premiered later that year in Toronto.[15] Snow recalled: "I was surprised to see people getting up and leaving very early in the projection of the film."[15] At a later showing in New York, "The audience catcalled, booed, whistled, and threw paper at the screen. The film ended, and surprisingly, there was also some strong applause. Two people in the audience jumped up and ran to the booth where I was standing with the projectionist. They were very excited and said, 'That was wonderful. Who did that?' I said that I was the maker of the film, and we had a short conversation, and they introduced themselves: Andy Warhol and Gerard Malanga."[15] According to Snow, Bernard Stollman, founder of ESP-Disk, heard about the film and approached him about releasing the music on an album. Snow stated: "the idea came up after the film had been made and been shown and puzzled everyone... [Stollman] asked me whether I'd be interested, and actually I had very mixed feelings about it, because it was precisely made to be used in conjunction with the images that I made. I was making a film with this music, and to separate the two, I really had to argue myself into it. Which seems a bit strange, I suppose, but the intention was to use it in a certain way with certain kinds of images."[17]

Reception

Critics have compared the album with key free jazz recordings such as Ornette Coleman's earlier Free Jazz and John Coltrane's subsequent Ascension. John Litweiler regards it favourably in comparison because of its "free motion of tempo (often slow, usually fast); of ensemble density (players enter and depart at will); of linear movement".[18] Ekkehard Jost places it in the same company and comments on "extraordinarily intensive give-and-take by the musicians" and "a breadth of variation and differentiation on all musical levels," calling it "one of Ayler's very best recordings."[19] Richard Brody wrote that the album is "superior to those performances in its freer, truly group-oriented format, with no specified soloists and accompanists," stating that "the riotous revelry joins the joy of New Orleans traditions to the urbane furies of the day."[20] All About Jazz reviewer Clifford Allen described New York Eye and Ear Control as "a valuable window into the music's early history as well as what might have happened outside record dates, more than one is usually privy to."[21] Playwright and director Richard Foreman described his reaction to the conjunction of the film and the music as follows: "Mike Snow postulates an eye that stares at surfaces with such intensity... the image itself seems to quiver, finally gives way under the pressure. A deceptive beginning-silent: a flat white form sharply cut to the silhouette of a walking woman, for no apparent reason propped against trees, rocks seashore. But slowly-under attack by time, light and an incredible growing music so aggressive it begins to bypass the ear and attack the eyes habits of seeing. Each time a cut wipes away this absurd idiogram-woman, she reappears – supported against the threat of the destructive eye by the S-O-U-N-D! – that insists on building a space in which objects can sustain themselves."[22]

Track listing

Personnel

- Albert Ayler - tenor saxophone

- Don Cherry - trumpet

- John Tchicai - alto saxophone

- Roswell Rudd - trombone

- Gary Peacock - bass

- Sunny Murray - drums

References

- ↑ https://www.allmusic.com/album/r23567

- ↑ Cook, Richard; Brian Morton (2008). The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings. The Penguin Guide to Jazz (9th ed.). London: Penguin. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-14-103401-0.

- ↑ Swenson, J., ed. (1985). The Rolling Stone Jazz Record Guide. USA: Random House/Rolling Stone. p. 16. ISBN 0-394-72643-X.

- ↑ Weiss, Jason (2012). Always in Trouble: An Oral History of ESP-Disk, the Most Outrageous Record Label in America. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 141–144.

- 1 2 3 4 Weiss, Jason (2012). Always in Trouble: An Oral History of ESP-Disk, the Most Outrageous Record Label in America. Wesleyan University Press. p. 141.

- 1 2 3 Tsangari, Athina Rachel (September 17, 1999). "Expanding Cinema: Avant-Garde Artist Michael Snow". austinchronicle.com. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Weiss, Jason (2012). Always in Trouble: An Oral History of ESP-Disk, the Most Outrageous Record Label in America. Wesleyan University Press. p. 143.

- ↑ Weiss, Jason (2012). Always in Trouble: An Oral History of ESP-Disk, the Most Outrageous Record Label in America. Wesleyan University Press. p. 142.

- ↑ Snow, Michael. "New York Eye And Ear Control". lux.org.uk. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Snow, Michael (1994). The Collected Writings of Michael Snow. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 24.

- ↑ Regan, Patrick. "New York Eye And Ear Control". ayler.co.uk. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- 1 2 Schwartz, Jeff. "Albert Ayler: His Life and Music: Chapter 2: 1963-64". Archived from the original on 2010-12-06. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ↑ "Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, John Tchicai, Roswell Rudd, Gary Peacock, Sonny Murray – New York Eye And Ear Control". discogs.com. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ↑ "New York Eye & Ear Control". espdisk.com. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Taubin, Amy (May 2020). "Infinite Spirit: Michael Snow". filmcomment.com. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Weiss, Jason (2012). Always in Trouble: An Oral History of ESP-Disk, the Most Outrageous Record Label in America. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Weiss, Jason (2012). Always in Trouble: An Oral History of ESP-Disk, the Most Outrageous Record Label in America. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Litweiler, John (1984). The Freedom Principle: Jazz After 1958. Da Capo.

- ↑ Jost, Ekkehard (1975). Free Jazz. Da Capo. pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Brody, Richard (August 12, 2008). "New Releases: Albert Ayler". newyorker.com. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Allen, Clifford (June 15, 2008). "Albert Ayler: New York Eye And Ear Control". allaboutjazz.com. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Foreman, Richard. "New York Eye And Ear Control". lux.org.uk. Retrieved July 30, 2020.