| Necrotizing pneumonia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious disease, respirology |

Necrotizing pneumonia (NP), also known as cavitary pneumonia or cavitatory necrosis, is a rare but severe complication of lung parenchymal infection.[1][2][3] In necrotizing pneumonia, there is a substantial liquefaction following death of the lung tissue, which may lead to gangrene formation in the lung.[4][5] In most cases patients with NP have fever, cough and bad breath, and those with more indolent infections have weight loss.[6] Often patients clinically present with acute respiratory failure.[6] The most common pathogens responsible for NP are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae.[7] Diagnosis is usually done by chest imaging, e.g. chest X-ray, CT scan. Among these CT scan is the most sensitive test which shows loss of lung architecture and multiple small thin walled cavities.[3] Often cultures from bronchoalveolar lavage and blood may be done for identification of the causative organism(s).[8] It is primarily managed by supportive care along with appropriate antibiotics.[8] However, if patient develops severe complications like sepsis or fails to medical therapy, surgical resection is a reasonable option for saving life.[6][8]

History

NP in adults was first described in the 1940s, whereas in children it was reported later in 1994.[3] Necrotizing pneumonia is an ancient disease which was once a leading cause of death in both adults and children.[9] Its clinical features were presumably first outlined by Hippocrates.[9] Later, in 1826, René Laennec described these features in a more detailed fashion in his seminal work De l’auscultation médiate ou Traité du Diagnostic des Maladies des Poumon et du Coeur (A treatise on the diseases of the chest, and on mediate auscultation).[9][10] Although availability of appropriate antibiotics had made NP a rare disease, over the last two decades it has emerged as a severe complication of childhood pneumonia.[1]

Causative organisms

The most common pathogens responsible for NP are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae.[7] Other pathogens which are less likely to cause NP are bacteria like Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus anginosus group, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Streptococcus pyogenes, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, anaerobes like Fusobacterium nucleatum and Bacteroides fragilis; fungi like Aspergillus sp. and Histoplasma capsulatum; viruses like Influenza and Adenovirus.[7][3][9]

Children

Apart from Streptococcus pneumoniae (also known as Pneumococcus), several other organisms have appeared to cause necrotizing pneumonia in children since 2002.[1] Most of the aforementioned organisms have been reported to be associated with childhood NP, except that, K. pneumoniae is not a common cause in children.[3] However, Pneumococci and S. aureus are frequently responsible for it.[3] Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) covering serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F was introduced in the USA in 2000.[11][12] Consequently, non-PCV7 serotypes like 3, 5, 7F 19A emerged as new threats. Of this, serotypes 3 and 19A were particularly associated with NP.[3] In 2010 PCV7 was replaced by a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13). PCV13 includes all PCV7 serotypes plus six additional serotypes (1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F & 19A).[12] Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) producing S. aureus strains are oftentimes responsible for life-threatening necrotizing pneumonia in previously healthy children and young adults.[13] These PVL-producing strains are frequently methicillin resistant (MRSA).[3] In developing countries with high rates of HIV infection, Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the common cause of NP in children.[7]

Adults

Adults are more commonly affected by community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus, S. pneumoniae and K. pneumoniae. Gram-negative organisms like K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa are usually associated with pulmonary gangrene.[7]

Predisposing risk factors

Adults

Necrotizing pneumonia typically occurs in adult males who have coexisting health problems like diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, and corticosteroid therapy.[2] Other risk factors may include smoking, gastrectomy, history of substance use disorder or HIV/AIDS.[7]

Children

On the contrary, in most of the cases children of both sexes are affected equally.[3] Furthermore, it is unlikely that affected children have any underlying co-morbidities, but if any, asthma is the most common chronic disorder followed by recurrent otitis media.[3][1]

Relationship with viral infection

Group A streptococcus such as S. pyogenes, often preceded by varicella infection, may cause severe invasive infections and complicated childhood pneumonia.[2] Influenza virus infection substantially increases the risk of developing necrotizing pneumonia in children mostly by PVL-producing S. aureus followed by S. pneumoniae.[7] In the United States it is observed that NP has increased following influenza owing to the emergence of MRSA strain USA300 infections.[14]

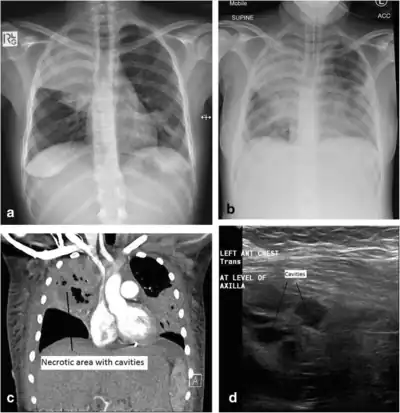

Additional imaging

a) Initial plain chest radiograph showing a dense right upper zone airspace opacity and lingula airspace changes, consistent with multi-focal pneumonia. The following images were performed 24 h later. b) Plain chest radiograph with the patient intubated and ventilated revealing cavitation in the right mid to upper zones, pleural effusion and more general airspace changes bilaterally. c) Computed tomography (CT) scan, coronal view, demonstrating non-enhancing area (necrotic) thin-walled cavities within the right upper lobe and lingula. d) Lung ultrasonographic image displaying thin-walled cavities in the lingula region of the left lung. This requires further clarification.[note 1]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Text was copied from this source, which is available under Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sawicki, G. S.; Lu, F. L.; Valim, C.; Cleveland, R. H.; Colin, A. A. (2008-03-05). "Necrotising pneumonia is an increasingly detected complication of pneumonia in children". European Respiratory Journal. 31 (6): 1285–1291. doi:10.1183/09031936.00099807. ISSN 0903-1936. PMID 18216055.

- 1 2 3 Tsai, Yueh-Feng; Ku, Yee-Huang (2012). "Necrotizing pneumonia". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 18 (3): 246–252. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283521022. ISSN 1070-5287. PMID 22388585.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Masters, I. Brent; Isles, Alan F.; Grimwood, Keith (July 25, 2017). "Necrotizing pneumonia: an emerging problem in children?". Pneumonia. 9 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s41479-017-0035-0. ISSN 2200-6133. PMC 5525269. PMID 28770121.

- ↑ Scotta, Marcelo C.; Marostica, Paulo J.C.; Stein, Renato T. (2019). "Pneumonia in Children". Kendig's Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children. Elsevier. p. 435.e4. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-44887-1.00025-0. ISBN 978-0-323-44887-1. S2CID 81700501.

- ↑ Widysanto, Allen; Liem, Maranatha; Puspita, Karina Dian; Pradhana, Cindy Meidy Leony (2020). "Management of necrotizing pneumonia with bronchopleural fistula caused by multidrug‐resistant Acinetobacter baumannii". Respirology Case Reports. 8 (8): e00662. doi:10.1002/rcr2.662. PMC 7507560. PMID 32999723.

- 1 2 3 Reimel, Beth Ann; Krishnadasen, Baiya; Cuschieri, Joseph; Klein, Matthew B; Gross, Joel; Karmy-Jones, Riyad (January 1, 2000). "Surgical management of acute necrotizing lung infections". Canadian Respiratory Journal. 13 (7): 369–373. doi:10.1155/2006/760390. PMC 2683290. PMID 17036090.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Krutikov, Maria; Rahman, Ananna; Tiberi, Simon (2019). "Necrotizing pneumonia (aetiology, clinical features and management)". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 25 (3): 225–232. doi:10.1097/mcp.0000000000000571. ISSN 1070-5287. PMID 30844921. S2CID 73507080.

- 1 2 3 Chatha, Neela; Fortin, Dalilah; Bosma, Karen J (February 19, 2021). "Management of necrotizing pneumonia and pulmonary gangrene: A case series and review of the literature". Canadian Respiratory Journal. 21 (4): 239–245. doi:10.1155/2014/864159. PMC 4173892. PMID 24791253.

- 1 2 3 4 Spencer, David A.; Thomas, Matthew F. (September 1, 2014). "Necrotising pneumonia in children". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 15 (3): 240–245. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2013.10.001. ISSN 1526-0542. PMID 24268096. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ↑ "National Library of Medicine". Digital Collections. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ↑ Benedictis, Fernando M de; Kerem, Eitan; Chang, Anne B; Colin, Andrew A; Zar, Heather J; Bush, Andrew (September 12, 2020). "Complicated pneumonia in children". The Lancet. 396 (10253): 786–798. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31550-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 32919518. S2CID 221590241. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- 1 2 Kaur, Ravinder; Casey, Janet R.; Pichichero, Michael E. (February 21, 2021). "Emerging Streptococcus pneumoniae Strains Colonizing the Nasopharynx in Children after 13-Valent (PCV13) Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccination in Comparison to the 7-Valent (PCV7) Era, 2006-2015". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 35 (8): 901–6. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000001206. PMC 4948952. PMID 27420806.

- ↑ Gillet, Yves; Issartel, Bertrand; Vanhems, Philippe; Fournet, Jean-Christophe; Lina, Gerard; Bes, Michèle; Vandenesch, François; Piémont, Yves; Brousse, Nicole; Floret, Daniel; Etienne, Jerome (March 2, 2002). "Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients". The Lancet. 359 (9308): 753–759. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07877-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 11888586. S2CID 20400336. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ↑ Tenover FC, Goering RV (2009). "Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300: origin and epidemiology". J Antimicrob Chemother. 64 (3): 441–6. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp241. PMID 19608582.