A nabob /ˈneɪbɒb/ is a conspicuously wealthy man deriving his fortune in the east, especially in India during the 18th century with the privately held East India Company.[1]

Etymology

Nabob is an Anglo-Indian term that came to English from Urdu, possibly from Hindustani nawāb/navāb,[2] borrowed into English during British colonial rule in India.[3] It is possible this was via the intermediate Portuguese nababo, the Portuguese having preceded the British in India.[4]

The word entered colloquial usage in England from 1612. Native Europeans used nabob to refer to those who returned from India after having made a fortune there.[5][6]

In late 19th century San Francisco, rapid urbanization led to an exclusive enclave of the rich and famous on the west coast who built large mansions in the Nob Hill neighborhood. This included prominent tycoons such as Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University and other members of The Big Four who were known as nabobs, which was shortened to nob, giving the area its eventual name.[7]

The term was used by William Safire in a speech written for United States Vice President Spiro Agnew in 1970, which received heavy media coverage. Agnew, increasingly identified with his attacks on critics of the Nixon administration, described these opponents as "nattering nabobs of negativism".[8][9]

History

The English use of nabob was for a person who became rapidly wealthy in a foreign country, typically India, and returned home with considerable power and influence.[10] In England, the name was applied to men who made fortunes working for the East India Company and, on their return home, used the wealth to purchase seats in Parliament.[11][12]

A common fear was that these individuals – the nabobs, their agents, and those who took their bribes – would use their wealth and influence to corrupt Parliament. The collapse of the Company's finances in 1772 due to bad administration, both in India and Britain, aroused public indignation towards the Company's activities and the behaviour of the Company's employees.[11] Samuel Foote gave a satirical look at those men who had enriched themselves through the East India Company in his 1772 play, The Nabob.

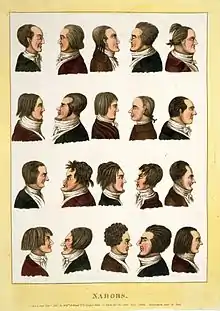

Nabobs became immensely popular figures within satirical culture in Britain, often depicted as lazy and materialistic, as well as a lack of temperance when regarding economic affairs in India. Nabobs typically came from middle-class backgrounds and tended to be of Caledonian origin, often being seen as low born social climbers.[13] Nabobs were often seen as challenging traditional values of middle-class British masculinity, as their weak moral grounds projected an effeminate symbol of a virtuous British culture. During the late 18th century, Britain was already struggling to define itself within its own imperial system—one that exposed cultural issues as well as growing the nation financially and socially. By taming the indulgent, uncultivated Nabob, and reintegrating both its character and wealth into sophisticated British society, the empire could reassert their vision of masculinity as well as push the image of an ethically upright middle class.[14] Beliefs that Nabobs, which typically worked as merchants and traders, had overstepped the unspoken socio-economic boundary through the surplus of riches in Asia quickly circulated. Nabobs quickly became weak-minded figures that had given in to the sensual temptation of colonial India that so many generations before them had been successful in resisting. Additionally, ideas of the Nabob’s unfettered opulence and aspiration to rise to governmental positions by unjustly purchasing Parliament seats were condensed into a satirical character.[15]

Often seen as traitorous, Nabobs indulged in Indian culture, with many learning the native languages, consuming native foods, and dressing themselves in native attire. However, Nabobs never sought to adopt the Mughal practices of late 18th century India. Rather, the goal was to appeal to Mughal authority in order to succeed in the line of power. When wearing native garments, the appeal was one of wearing a costume, not a piece of everyday garb, reflecting the need to reconcile British aesthetics with the politics needs of Nabob work.[1] Nabobs were also criticized for their lack of traditional domestic marriage, as many would go on to marry Indian women and father Indian children. These women, also called bibis, were typically of wealthy Muslim origin, and would go on to run a mixed culture household with elements from both Indian and British society. Nabobs were known to have multiple bibis, though this was not true of every case. As a result, many Nabobs were seen as rejecting traditional British values and culture and falling prey to the overwhelming opulence of South Asia, a belief that would only worsen as their governmental role evolved.[16]

Much of the criticism directed towards Nabobs was rooted in their leadership in Parliament. Following the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Nabobs began amassing considerable wealth, which they directed toward purchasing large estates, securing advantageous marriages, and purchasing seats in Parliament. Though Nabobs only held twelve seats in Parliament during 1761, this number soon rose to be near thirty by 1780.[13] Despite their control in the government, Nabobs were not a united front, rather, they remained apathetic towards political or economic decisions unless they pertained to Indian affairs. Instead, they used their power to further their financial agendas, often using their position to reassert pressure on the East India Company’s directors and shareholders. In Henry Thompson’s The Intrigues of a Nabob, published in 1780, he writes that the Nabob “can govern the Eastern world as he pleases” and “cares not at what expense he acquires his power.”[17] This reveals the malice that many British people held towards the elite of the East India Company. There was no part of the Nabob’s earnings or role in Parliament that was deemed to be righteous, instead perceived as being the outcome of fraud, greed and cruelty. Though malpractice and bribery were not uncommon occurrences prior to the Nabob’s role, British society regarded it as excessive and exaggerated.[13] Furthermore, complaints of Nabobs’ residences in England were common, as they would drive up housing prices and limit the resources of neighborhoods. Many Nabobs were so exceedingly wealthy that they could afford to purchase estates regardless of exorbitant costs, thus overriding economic factors of supply and demand that limited the rise of prices. These large estates typically required extensive staffing, resulting in shortages in the neighborhood.[13]

This perception of the pernicious influence wielded by nabobs in both social and political life led to increased scrutiny of the East India Company. A number of prominent Company men underwent inquiries and impeachments on charges of corruption and misrule in India.[11] Warren Hastings, first Governor-General of India, was impeached in 1788 and acquitted in 1795 after a seven-year-long trial. Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive, MP for Shrewsbury, was forced to defend himself against charges brought against him in the House of Commons.[5] Pitt's India Act of 1784 gave the British government effective control of the private company for the first time. The new policies were designed for an elite civil service career that minimized temptations for corruption.[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 Smylitopoulo, Christina (2012). "Portrait of a Nabob: Graphic Satire, Portraiture, and the Anglo-Indian in the Late Eighteenth Century" (PDF). Canadian Art Review. 37 (1).

- ↑ "nabob". oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

from Portuguese nababo or Spanish nabab, from Urdu; see also nawab

- ↑ The Slang dictionary, etymological, historical and anecdotal. London: Chatto and Windus. 1874. p. 233.

- ↑ "What did it mean to be nabobs? – Yoforia.com". Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- 1 2 "nabobical – Word Origin & History – nabob". dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

1612, "deputy governor in Mogul Empire," Anglo-Indian, from Hindi nabab, from Arabic nuwwab

- ↑ "nabob (governor)". Memidex.com. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

Etymology:Hindi nawāb, nabāb, from Arabic nuwwāb, plural of nā'ib, deputy, active...

- ↑ "Nob Hill - A Touch of Class". Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Nechtman, Tillman W. (2010). Nabobs: Empire and Identity in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-176353-0.

- ↑ Morrow, Lance (30 September 1996). "Naysayer to the nattering nabobs". Time. Archived from the original on 10 November 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ J. Albert Rorabacher (2016). Property, Land, Revenue, and Policy: The East India Company, C.1757–1825. Taylor & Francis. p. 236. ISBN 9781351997348.

- 1 2 3 "The East India Company and public opinion - Nabobs". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

see also right side Related Information – Did you know?

- ↑ "nawab, English nabob". britannica.com. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Lawson, Philip; Phillips, Jim (October 1984). ""Our Execrable Banditti": Perceptions of Nabobs in Mid-Eighteenth Century Britain". Albion. 16 (3): 225–241. doi:10.2307/4048755. ISSN 0095-1390.

- ↑ Gould, Marty (2011). Nineteenth century theatre and the Imperial encounter. Routledge advances in theatre and performance studies. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-88984-1.

- ↑ Smylitopoulos, Christina (2012). "Portrait of a Nabob: Graphic Satire, Portraiture, and the Anglo-Indian in the Late Eighteenth Century". RACAR: revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 37 (1): 10–25. ISSN 0315-9906.

- ↑ Sharma, Yoti Pandey (2019). "Sociability in Eighteenth-Century Colonial India: The Nabob, the Nabobian Kothi, and the Pursuit of Leisure". Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review. 31 (1): 7–24. ISSN 1050-2092.

- ↑ Thompson, Henry (1780). The Intrigues of a Nabob: Or, Bengal the Fittest Soil for the Growth of Lust, Injustice and Dishonesty. ISBN 978-0343197889.

- ↑ Tristram Hunt (2014). Cities of Empire: The British Colonies and the Creation of the Urban World. Henry Holt. p. 208. ISBN 9780805096002.