| Mugulü 木骨閭 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tribal chief | |||||||

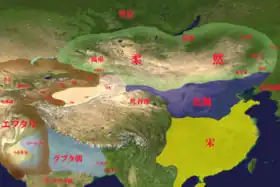

Map representing rourans well to the north, located at the epicenter of the eastern steppe, in comparison to other states in its vicinity, with its area of influence extremely west and east, bordering the northern Wei state (北魏), appearing under the bluish color. | |||||||

| Tribal chief of the Rouran tribe | |||||||

| Reign | 330–? or 308–316 | ||||||

| Coronation | 330 or 308, Hetulin | ||||||

| Predecessor | Chiefdom established | ||||||

| Successor | Yujiulü Cheluhui | ||||||

| Born | 3rd century, before 277 | ||||||

| Died | 4th century, 316 or after 330 | ||||||

| Issue | |||||||

| |||||||

| Clan | Yujiulü clan | ||||||

| Dynasty | Rouran tribe | ||||||

| Religion | Tengrism | ||||||

| Occupation | Dai soldier, Xianbei slave (former and uncertain) | ||||||

| Ethnicity | Proto-Mongol | ||||||

| Cause of death | Unknown | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 木骨閭 (trad.) 木骨闾 (simp.) | ||||||

| |||||||

Mugulü (Chinese: 木骨閭; pinyin: Mùgǔlǘ) was a legendary warrior and chieftain in the Mongolian Plateau during the period when it was under the rule of tribes and peoples originating from the fragmentation of the failed and crumbling Xianbei confederation. The term "Mongol" is a likely derivation from his name.[1]

Biography

Mugulü was likely born before AD 277, at the end of Tuoba Liwei's reign.[2][3]

Little is known about his childhood. His date and place of birth, and the names of his parents or those of his consorts, are not disclosed in Book of Wei.[4]

He served in the Xianbei army under the leadership of the Tuoba tribal chief, Tuoba Yilu (295–316) of Dai. Possibly a legendary figure, he was a fugitive slave according to Chinese sources, however one researcher thinks that this is questionable and assumes that Chinese authors frequently ascribed lowly origins to the Northern nomads, as a way of emphasizing their barbarity.[5] According to Barbara West, Mugulü believe to have been a slave of the Xianbei.[6]

Youth

According to Chinese chronicles, Mugulü was a slave of unknown origin who was captured and enslaved by a Tuoba raider cavalryman[2] during the reign of chief Liwei (220-277)[2][7] of the Tuoba, a Xianbei clan[8][9][10][11] most likely of Proto-Mongolic origin.[12] The anecdote of his enslaved status has been rejected by modern scholars as "a typical insertion by the Chinese historians intended to show the low birth and barbarian nature of the northern nomads."[5]

Mugulü's career and his escape through the Gobi

According to the Book of Wei, after either having matured (being 30 or older) or because of his strength,[13] Mugulü was emancipated and became a warrior in the Tuoba Xianbei cavalry, under the leadership of Tuoba Yilu of Dai (307–316).[14] However, he tarried past the deadline and was sentenced to death by beheading.[15] He vanished and hid in the Gobi desert,[16][17] but then gathered a hundred or more other escapees.[18] They sought refuge under a neighboring tribe of Tiele people[16][17] called Hetulin (紇突隣).[19][20][21][22]

It is not known when Mugulü died; sources say 316 AD.[23]

Family and succession

When Mugulü died, his son Yujiulü Cheluhui acquired his own tribal horde and either Cheluhui was or his tribe called themselves Rouran.[24][25] Cheluhui's government was marked by [nomadism and peace,[26] but they remained subjects to the Xianbei Tuobas.[27][24]

His descendants and successors were:[28]

- Yujiulü Cheluhui, son

- Yujiulü Tunugui, grandson

- Yujiulü Bati, great-grandson

- Yujiulü Disuyuan, great-great-grandson

Personal name

According to the Chinese chronicles, the Xianbei (Sianbi) master called the captive Mugulü, a Xianbei word glossed as "bald-headed" (首禿)[29] possibly owing to his appearance, his hairline starting at his eyebrow's level,[30][31] and because he did not remember his name and surname.[32] This was reconstructed as Mongolic Muqur (Mukhur) or Muquli (Mukhuli) presumably "round, smooth" by Japanese researcher Shiratori Kurakichi.[33][34] Alexander Vovin instead proposes that Mùgúlǘ (木骨閭), in reconstructed Middle Chinese *muwk-kwot-ljo, transcribed Tuoba Xianbei *moqo-lo ~ muqo-lo 'bald head', which is analysable as 'one [who/]which has cut off/fallen off [hair]' and cognate with Mongolic lexical items like Mongolian: Мухар (Written Mongolian moɣutur ~ moqutur 'blunt, hornless, bald tail' (cf. Chinese gloss as 禿尾 'bald tail'), moqu-ɣar, Middle Mongol muqular 'hornless', moqo-dag 'blunt'; all of those are from Proto-Mongolic *muqu 'to be cut off, break off, fall off', which in turn would produce the semantic variation 'blunt ~ hornless ~ hairless ~ bald').[35]

Clan name

According to the Book of Wei, the dynasty founded by Mugulü's descendants was called Yujiulü, which sounds superficially like Mugulü, and thus the Yujiulü clan (郁久閭氏, reconstructed Middle Chinese: ʔjuk kjǝu ljwo[36]) emerged.[37][38] Róna-Tas suggests that Yujiulü rendered *ugur(i) > Uğur, a secondary form of Oğur.;[39] Peter B. Golden additionally proposes connection with Turkic uğurluğ "feasible, opportune", later "auspicious fortunate" or oğrï "thief", an etymology more suited to the dynasty's founder's activities; additionally Yujiulü may be comparable to Middle Mongolian uğuli "owl" (> Khalkha ууль uul'), as personal names based on bird names are common in Mongolic.[40]

See also

Succession

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Г. Сүхбаатар (1992). "Монгол Нирун улс" [Mongol Nirun (Rouran) state]. Монголын эртний түүх судлал, III боть [Historiography of Ancient Mongolia, Volume III] (in Mongolian). Vol. 3. pp. 330–550.

- 1 2 3 Weishu vol. 103 始神元之末,掠騎有得一奴 tr. "In the beginning of the end of the Shenyuan, a [Tuoba] raider cavalryman acquired a slave"

- ↑ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54-56.

- ↑ Weishu vol. 103 section "Ruru"

- 1 2 Kradin NN (2005). "From Tribal Confederation to Empire: The Evolution of the Rouran Society". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 58 (2): 159. doi:10.1556/AOrient.58.2005.2.3. JSTOR 23658732.

- ↑ West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 686-687. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

Yujiulu Mugulu, the grandfather of Yujiulu Shelun, who was the first to unite the various Rouran clans, is believed to have been a slave of the Xianbei...

- ↑ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 55.

- ↑ Wei Shou. Book of Wei. Vol. 1

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 60–65. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. - A.D. 907. p. 131.

- ↑ Tseng, Chin Yin (2012). The Making of the Tuoba Northern Wei: Constructing Material Cultural Expressions in the Northern Wei Pingcheng Period (398-494 CE) (PhD). University of Oxford. p. 1.

- ↑

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity", Early China. p. 20

- ↑ Weishu vol. 103. The phrase "木骨閭既壯" is translatable as literally "Mugulü, because of [his] robustness", or - figuratively - "Mugulü, because of [his] maturity"; cf. Liji "Quli I txt: "三十曰壯" tr: "When he is thirty, we say, 'He is at his maturity;'" by James Legge

- ↑ Weishu vol. 103 "免奴為騎卒。穆帝時" tr. "[he was] release[d] from slavery and made a cavalry soldier, during the time of Emperor Mu (of Dai)"

- ↑ Weishu vol. 103 "坐後期當斬"

- 1 2 依紇突隣部 諸本及北史卷九八蠕蠕傳「紇」作「純」。按本卷高車傳末即附有紇突隣部,卷二太祖紀登國五年五月及十二月、皇始二年二月見此部,都作「紇突隣」,「純」乃形近而訛,今改正。

- 1 2 Weishu 554, Vol. 103.

- ↑ Weishu vol. 103 "亡匿廣漠谿谷間, 逋逃得百餘人

- ↑ Weishu vol. 103, Ruru "依紇突隣部" tr. "[They] relied on the Hetulin tribe"

- ↑ The corresponding passage in Beishi vol. 98 Ruru reads "依純突鄰部" tr. "[They] relied on the Chuntulin tribe" or "[They] relied on the pure Tulin tribe"

- ↑ Both Weishu, Vol. 103, Gaoche and Beishi Vol. 98, Gaoche have "又有紇突隣" tr. "[There] were also the Hetulin tribe"

- ↑ Bozan 1962, p. 225.

- ↑ Lee 2015, pp. 51–52.

- 1 2 Pohl 2018, p. 33.

- ↑ Weishu Vol. 103 "木骨閭死,子車鹿會雄健,始有部眾,自號柔然" "Mugulü died; [his] son Cheluhui, virile and robust, began to gather the tribal multitude, [his/their] self-appellation Rouran"

- ↑ Weishu, vol. 103 "車鹿會既為部帥,歲貢馬畜、貂豽皮,冬則徙度漠南,夏則還居漠北。

- ↑ Weishu Vol. 103 "而役屬於國。" tr. "yet [Cheluhui/Rouran] [was/were] vassal(s) of (our) state.

- ↑ Grousset (1970), pp. 61, 585, n. 91.

- ↑ Weishu vol. 103 "其主字之曰木骨閭。「木骨閭」者,首禿也。"

- ↑ Weishu, "Vol. 103" "髮始齊眉 [...] 首禿也"

- ↑ Weishu Vol. 103 "髮始齊眉"

- ↑ vol. 103 "忘本姓名"

- ↑ 白鳥庫吉 1910; 内田吟風 1971: 218.

- ↑ Ginfu 1971, p. 218, note 4.

- ↑ Vovin, Alexander. 2007. "Once again on the Tabγač language", Mongolian Studies, XXIX: 200-202

- ↑ Golden, Peter B. (2018). "The Stateless Nomads of Central Eurasia". Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity. pp. 317–332. doi:10.1017/9781316146040.024. ISBN 9781316146040. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Weishu Vol. 103 txt. "木骨閭與郁久閭聲相近,故後子孫因以為氏。" tr. "Mugulü and Yujiulü sound similar; hence [Mugulü's] descendants later used as surname"

- ↑ Lee, Joo-Yup (2015-12-04). Qazaqlïq, or Ambitious Brigandage, and the Formation of the Qazaqs: State and Identity in Post-Mongol Central Eurasia. BRILL. p. 52. ISBN 9789004306493.

- ↑ Róna-Tas, András. (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the early Middle Ages : an introduction to early Hungarian history. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 9639116483. OCLC 654357432.

- ↑ Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 55.

Further reading

- Beishi vol. 98 section "Ruru"

- Weishu vol. 103