| Merseytram | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Locale | Merseyside |

| Transit type | Tram |

| Number of lines | 3 |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | Cancelled |

| Operator(s) | Merseytravel |

Merseytram was a proposed light rail system for Merseyside, England. Originally proposed in 2001, forming part of the Merseyside Local Transport Plan, it was to consist of three lines, connecting the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley with central Liverpool. The project was postponed due to funding problems before eventually being formally closed down by Merseytravel in October 2013.[1]

Planned services

City Centre Loop

The hub of the Merseytram system was to be a loop around Liverpool city centre. Designed to be constructed in two stages (simultaneous with Line One and Line Two), the loop would have covered major transport hubs (Liverpool Lime Street, for mainline services; Moorfields for the Merseyrail network; Paradise Street Interchange for city bus services; and the Pier Head for Mersey Ferry services). Other destinations included the Kings Dock Arena & Conference Centre, the main shopping centre (including the Liverpool One retail development) and tourist attractions such as St George's Hall, Tate Liverpool, the Albert Dock and the World Museum and Walker Art Gallery.

Line One

Line One was to leave the City Centre Loop at Monument Place and head in a north east direction along London Road and via the Royal Liverpool University Hospital to West Derby Road and out to West Derby and Croxteth, terminating at Kirkby; a distance of some 11 miles (18 km).

Line Two

Line Two, which was intended to open in 2008, would leave the city centre loop at Lime Street and head east to Prescot and Whiston, via Paradise Street, Knotty Ash and Page Moss.

Line Three

Line Three would have terminated at Liverpool John Lennon Airport via Liverpool South Parkway and may have used some running alongside the Edge Hill to Runcorn line.

History

19th Century

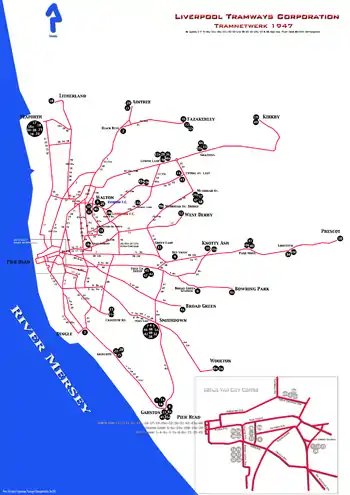

Liverpool had an extensive tram network in the early-20th century, which was one of the most advanced in the UK. The network included large sections of reserved track in the centre reservations and side reservations of the dual carriageway system that was developed by Liverpool City Engineer, John Brodie. Brodie understood that ordinary railway sleeper track was less expensive than road tram track and thereby justified the increased width of the new roads. The reservations also allowed trams to by-pass road congestion.

20th Century

After World War II, trams fell out of favour and Liverpool City Council voted to scrap the system in 1957. The controversial decision was made by the casting vote of the mayor – a protocol requirement in the event of a hung vote.

During the 1960s and 1970s, public transport development in Liverpool concentrated on integration and expansion of the dispersed urban rail lines into a complete rapid transit network with bored tunnels and stations in the centre serving a large part of the city and Merseyside. The resulting metro-like network was called Merseyrail. One of the main proposals was the creation of an Outer Rail Loop by the electrification of a former passenger route through the eastern suburbs, a six platform underground interchange station at Broad Green, and using existing lines in the west of the city. This proposal was unsuccessful due to financial problems and political opposition. The eastern section of the Outer Loop was not built leaving the eastern districts of the city unserved.

In the mid 1990s, a new proposal was formulated to serve the eastern suburbs remote from the rail network. This was known as MRT, the Mersey Rapid Transit and would have consisted of articulated electric trolley buses using an electronic guidance system. The proposed route was from the City Centre to Page Moss via Mount Pleasant.

The scheme was rejected at public inquiry - one of the reasons given being the reopening of pedestrianised routes in the city centre to road vehicles. In response, Merseytravel proposed the Merseytram three line system.

Unlike the Manchester Metrolink, which used heavy rail lines and stations serving the towns around Manchester and street running in Manchester city centre, Merseytram was a stand-alone 100% street running network. Unable to build an underground rail in the city centre after the cancellation of the Picc-Vic tunnel scheme, Greater Manchester designed Metrolink as a mixture of commuter rail and street running trams where because of cost constraints tunnels could not be bored. Unlike Manchester, Liverpool has used and unused tunnels under its city centre. Metrolink acted as a fast commuter rail system on the outskirts and a street running tram in Manchester city centre. Merseytram did not use any Merseyrail track and branch off to disconnected parts of the city not served by rail. Neither did Merseytram use mothballed tunnels or trackbeds in the Liverpool area, of which the city has in abundance. The lack of integration with Merseyrail was criticized.[2]

Scheme development

The project was accepted by Secretary of State for Transport Alistair Darling in December 2002. After extensive public consultation, the contract to build the first two lines was initially awarded in late 2004, but problems with the tender bid with regards to the best value forced the cancellation of the contract and the reopening of the tender process. In April 2005, the M-Pact consortium of GrantRail and Laing O’Rourke was named as the preferred bidder.[3]

On 21 December 2004, the Merseytram Line 1 Transport and Works Act application was approved by Darling. The line was originally intended to start construction on 1 July 2005 for a 2007 opening. Plans called for it to use Bombardier Flexity Swift trams.

The tram network had formed part of a larger regeneration project in the areas in which it was intended to run, related to Liverpool's award of European Capital of Culture in 2008. In the event, the need to avoid extensive street works during 2008 led to half of the city centre loop being removed from the Line One scheme for delivery as part of the subsequent Line Two.

Rejection

Budget for the first stage of the project was set at £225 million, with the Government of the United Kingdom providing £170 million of the cost. However, by 2005 rising costs had led to a new requirement of £238 million against a cost of £325 million.

The Government had refused any additions to the initial amount and asked the two councils that would be supporting Line One (Liverpool City Council and Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council) to make an agreement not to seek additional funding from the government if the project ran over budget.

Although some attempts to meet this request were made, Under-Secretary of State for Transport Derek Twigg felt that the assurances of the two councils that any shortfall would be met by Merseytravel and a £24 million contingency fund were insufficient and cancelled the scheme on 29 November 2005.

Efforts at revival

At the beginning of 2008 fresh hopes of reviving the tram project were raised. Keolis who would have been operating the trams originally, confirmed they are still on board and in ongoing talks with Merseytravel.

From 1 October 2008 new health and safety regulations were applied to light rail (trams) as well as to heavy rail (trains) meaning that required safety levels became higher and more expensive.

On 18 April 2008 a new bid for funds was requested by the Department for Transport, now seemingly considerably keener on the idea of trams on Merseyside.[4] High hopes that the long-awaited project was finally back on track were raised even further with another announcement, a few days later, that the new business case for Line 1 was to be submitted to the DfT in the second half of 2008.

It was published by the local press in May 2008 that if Everton Football Club's relocation to Kirkby, just outside Liverpool, was granted planning permission, Merseytram would be more likely to go ahead.[5] However, in November 2009, Everton's proposed stadium at Kirkby was rejected.[6]

In November 2009 Merseytravel was given permission from local councils to seek new funding from the Department for Transport, making the £450 million project become back on track.[7]

Compulsory Purchase Order

On 8 August 2013 a campaign group was set up to bring together the individuals and businesses affected by the compulsory purchase order that was in place for a number of years. The compulsory purchase has now officially expired. The aim of the campaign group was to seek compensation from Merseytram for the loss caused by the compulsory purchase order.[8] A Freedom of Information request was also submitted to Merseytravel on 8 August 2013 with a view of obtaining the details of all land/building owners affected by the compulsory purchase order.[9]

Future

Merseytram was placed as a priority project within Merseytravel's transport plan for 2006–2011, and alignments were preserved within all current and approved projects along the Line 1 route. The rights to construction were due to expire in February 2010 if construction had not begun, but the Council controversially issued 800 compulsory purchase orders despite no funding being in place to commence construction. The Council also approved the site of a park and ride at Gillmoss, off the East Lancashire Road to keep the planning permission alive.[10] The park and ride site was viewed as interim use for bus-visiting football fans on match days. The project remained without government recognition as a regional transport priority, which prevented access to the Merseyside regional transport funding allocation budget of the Department for Transport.

In 2009, the then Minister of State for Transport Sadiq Khan, in the words of Liverpool Council leader Warren Bradley "virtually kills off Merseytram once and for all."[11] The Merseytram project was formally closed by the Merseyside Integrated Transport Authority in October 2013.[12]

In June 2019 the Liverpool Echo reported early plans for a similar light-rail or trackless electric system to connect the Lime Street area of central Liverpool to the Knowledge Quarter and Paddington Village, a route which currently suffers from poor public transport connection and traffic congestion.[13] Under the provisional name of the 'Lime Line', the route would be part of a scheme to redevelop the area around the Adelphi Hotel.

Criticism

The route of Line One has caused some controversy. The fact that it would terminate at Kirkby, already served by a fast and frequent Merseyrail service, had led it to be seen as duplicating an existing service. Merseytravel responded by pointing out that Line One would serve a completely different market – an argument accepted by the inspector at the subsequent public inquiry.

There were also fears that the tram by taking one side of a dual carriageway at West Derby Road, would increase congestion on an already busy road. Merseytravel argued that congestion would be more likely to occur without the tram project and that improved junction design would serve to maintain capacity. Again, this argument was accepted by the inspector.[14]

Liverpool City councillor Stuart Monkcom has been vociferous in his opposition to the tram scheme, highlighting poor financial performance of other tram networks: "In 2006, for example, Manchester's Altram accounts showed a loss of £8m due to overoptimistic passenger projections, while in the West Midlands the Midland Metro, also operated by Altram, showed losses of about £16m. Worst of all, down in London, Tramtrack Croydon Ltd recorded debts of £100m and was seeking financial restructuring in order to continue trading."[15]

In response, critics stated that these arguments failed to recognise that these systems were all operated on a not for profit basis by the relevant PTEs. Tramtrack Croydon Ltd was bought out by Transport for London for £98m in 2008, TfL, which always set the fares had been paying the company £4 million a year in compensation for the commercially unviable fares under a 1996 agreement[16] however it recognised operational savings could be made from owning the system directly.

Councillor Monkcom suggested expansion to Merseyrail or reconstruction of the Liverpool Overhead Railway as preferable schemes to Merseytram.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ "Merseytram Statement - October 2013". Merseytravel. 25 October 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ↑ "Merseytram Inspector's Report" (PDF). Merseytravel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2011.

- ↑ Merseytram ready to start Railway Gazette International 1 May 2005

- ↑ Weston, Alan (18 April 2008). "Merseytram plan funding hopes revived". Liverpool Daily Post. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008.

- ↑ "Everton Ground Move strengthens the case for the trams". Liverpool Echo. 5 May 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- ↑ Bartlett, David (25 November 2009). "Where now for Everton FC, after Government rejects Kirkby plan?". Liverpool Daily Post. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ↑ "Tram project to seek new funding". BBC News. 28 November 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ↑ "Merseytram Compulsary Purchase Order (CPO) – Calling All Land/Building Owners!". Wordpress. 8 August 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ↑ "Land/building owners affected by Merseytram CPO". WhatDoTheyKnow. 8 August 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ↑ Schofield, Ben (9 March 2010). "£120million injection into Manchester tram network gives 'boost' to Merseytram". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Bartlett, David (19 October 2009). "EXCLUSIVE: The letter from Government that "virtually kills off Merseytram"". Liverpool Daily Post Blog. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011.

- ↑ "Merseytram Future Policy Framework - Update" (PDF). Merseytravel. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ↑ Thorp, Liam (27 June 2019). "Liverpool could get new light rail system to link parts of the city centre". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ↑ "Merseytram Inspector's Report" (PDF). Merseytravel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011.

- 1 2 Bartlett, David (19 February 2010). "Guest blog: Liberal Democrat Stuart Monkcom on the Merseytram 'myths'". Liverpool Daily Post Blog. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ↑ "TfL announces plans to take over Tramlink services". Transport for London. 17 March 2008. Archived from the original on 12 April 2008.

External links

- "Merseyside tram system plan axed". BBC News. 29 November 2005.

- Waddington, Marc (2 August 2013). "Merseytram scheme finally reaches the end of the line". Liverpool Echo.