| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

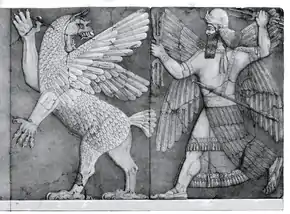

Chaos Monster and Sun God |

|

|

In Sumerian mythology, a me (𒈨; Sumerian: me; Akkadian: paršu) is one of the decrees of the divine that is foundational to Sumerian religious and social institutions, technologies, behaviors, mores, and human conditions that made Mesopotamian civilization possible. They are fundamental to the Sumerian understanding of the relationship between humanity and the gods.

Mythological origin and nature

The mes were originally collected by Enlil and then handed over to the guardianship of Enki, who was to broker them out to the various Sumerian centers, beginning with his own city of Eridu and continuing with Ur, Meluhha, and Dilmun. This is described in the poem, "Enki and the World Order" which also details how he parcels out responsibility for various crafts and natural phenomena to the lesser gods. Here the mes of various places are extolled but are not themselves clearly specified, and they seem to be distinct from the individual responsibilities of each divinity as they are mentioned in conjunction with specific places rather than gods.[1] After a considerable amount of self-glorification on the part of Enki, his daughter Inanna comes before him with a complaint that she has been given short shrift on her divine spheres of influence. Enki does his best to placate her by pointing out those she does in fact possess.[2]

There is no direct connection implied in the mythological cycle between this poem and that which is our main source of information on the mes, "Inanna and Enki: The Transfer of the Arts of Civilization from Eridu to Uruk", but once again Inanna's discontent is a theme. She is the tutelary deity of Uruk and desires to increase its influence and glory by bringing the mes to it from Eridu. She travels to Enki's Eridu shrine, the E-abzu, in her "boat of heaven", and asks the mes from him after he is drunk, whereupon he complies. After she departs with them, he comes to his senses and notices they are missing from their usual place, and on being informed what he did with them attempts to retrieve them. The attempt fails and Inanna triumphantly delivers them to Uruk.[3]

The Sumerian tablets never actually describe what any of the mes look like, but they are clearly represented by physical objects of some sort. Not only are they stored in a prominent location in the E-abzu, but Inanna is able to display them to the people of Uruk after she arrives with them in her boat. Some of them are indeed physical objects such as musical instruments, but many are technologies like "basket weaving" or abstractions like "victory". It is not clarified in the poem how such things can be stored, handled, or displayed.

Not all of the mes are admirable or desirable traits. Alongside functions like "heroship" and "victory" are "the destruction of cities", "falsehood", and "enmity". The Sumerians apparently considered such evils and sins an inevitable part of humanity's experience in life, divinely and inscrutably decreed, and not to be questioned.[4]

List of mes

Although more than one hundred mes appear to be mentioned in the latter myth, and the entire list is given four times, the tablets upon which it is found are so fragmentary that we have only a little over sixty of them. In the order given, they are:[5]

- ENship

- Godship

- The exalted and enduring crown

- The throne of kingship

- The exalted sceptre

- The royal insignia

- The exalted shrine

- Shepherdship

- Kingship

- Lasting ladyship

- "Divine lady" (a priestly office)

- Ishib (a priestly office)

- Lumah (a priestly office)

- Guda (a priestly office)

- Truth

- Descent into the nether world

- Ascent from the nether world

- Kurgarra (a eunuch, or, possibly, ancient equivalent to modern concepts of androgyne or transgender[6])

- Girbadara (a eunuch)

- Sagursag (a eunuch, entertainers related to the cult of Inanna[7])

- The battle-standard

- The flood

- Weapons (?)

- Sexual intercourse

- Prostitution

- Law (?)

- Libel (?)

- Art

- The cult chamber

- "hierodule of heaven"

- Gusilim (a musical instrument)

- Music

- Eldership

- Heroship

- Power

- Enmity

- Straightforwardness

- The destruction of cities

- Lamentation

- Rejoicing of the heart

- Falsehood

- Art of metalworking

- Scribeship

- Craft of the smith

- Craft of the leatherworker

- Craft of the builder

- Craft of the basket weaver

- Wisdom

- Attention

- Holy purification

- Fear

- Terror

- Strife

- Peace

- Weariness

- Victory

- Counsel

- The troubled heart

- Judgment

- Decision

- Lilis (a musical instrument)

- Ub (a musical instrument)

- Mesi (a musical instrument)

- Ala (a musical instrument)

References

Citations

- ↑ Kramer 1963, p. 122.

- ↑ Kramer 1963, pp. 171–173.

- ↑ Kramer 1963, pp. 160–162.

- ↑ Kramer 1963, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Kramer 1963, p. 116. Although they are numbered consecutively here, there is an unexplained jump in the numbering as Kramer gives it, with four items missing between "art of metalworking" and "scribeship". It presumably represents a place where it is clear in the texts that items occur, but are unintelligible.

- ↑ Meador 2001, p. 204.

- ↑ Meador 2001, p. 163.

Works cited

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45238-7.

- Meador, Betty De Shong (2001). Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.

Further reading

- Emelianov, Vladimir (2009). Shumerskij kalendarnyj ritual (kategorija ME i vesennije prazdniki) (Calendar ritual in Sumerian religion and culture (ME's and the Spring Festivals)). St.-Petersburg, Peterburgskoje vostokovedenje, Orientalia.

- Farber-Flügge, Gertrud (1973). Der Mythos "Inanna und Enki" unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Liste der me (The myth of "Inanna and Enki" under special consideration of the list of the me). PhD thesis, University of Munich, Faculty of Philosophy; Rome: Biblical Institute Press. Vol. 10 of Studia Pohl, Dissertationes scientificae de rebus orientis antiqui.

- Halloran, John A. (1999-08-11). "Sumerian Lexicon, version 3.0" (PDF). pp. 1, 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-01-20. Retrieved 2006-07-24.

External links

- The Sumerian Mythology FAQ

- Inana and Enki cuneiform source translation at ETCSL (The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, University of Oxford, England)