Maurice Rossel (1916 or 1917 – after 1997) was a Swiss doctor and International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) official during the Holocaust. He is best known for visiting Theresienstadt concentration camp on 23 June 1944; he erroneously reported that Theresienstadt was the final destination for Jewish deportees and that their lives were "almost normal". His report, which is considered "emblematic of the failure of the ICRC" during the Holocaust, undermined the credibility of the more accurate Vrba-Wetzler Report and misled the ICRC about the Final Solution. Rossel later visited Auschwitz concentration camp. In 1979, he was interviewed by Claude Lanzmann; based on this footage, the 1997 film A Visitor from the Living (fr) was produced.

Early life

Information on Rossel's biography is limited. He was born in 1916 or 1917. He was born in Tramelan, a village in the French speaking part of the Canton of Bern. Until his retirement in the early 1980 decade he was a very appreciated generalist in his home village. [lower-alpha 1] His background was typical of International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) representatives at the time, as he was a young man, a Swiss Army officer, a doctor, and a Protestant. He later said that his main motivation to join the Red Cross was to avoid a posting to the Swiss border guard.[1]

ICRC career

Between 12 April 1944 and 1 January 1945, Rossel was based in Berlin, a posting he obtained because of his fluent German. During this period, Rossel participated in seventeen missions, each time visiting several prisoner of war camps. Four of these missions were to camps in the Sudetenland, which, along with his good relationship with Dr. Roland Marti, the head of the Berlin Red Cross delegation, may have influenced his selection for the Theresienstadt visit, despite his inexperience.[1] According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, his visits to camps in Upper Silesia put him into contact with prisoners who were aware of the gassing of prisoners at Auschwitz concentration camp, but Rossel later said that he had no knowledge of that.[3]

Theresienstadt visit

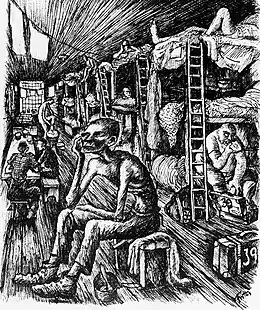

In 1943, the ICRC came under increasing pressure from Jewish organizations and the Czechoslovak government-in-exile to intervene in favor of Jews, in light of accumulating reports of the extermination of Jews by the Nazi regime.[lower-alpha 2] In an attempt to preserve its credibility and preeminence as a humanitarian organization, the ICRC requested to visit Theresienstadt concentration camp in November 1943.[4] The visit was also part of a larger program of verification that packages sent by the ICRC to concentration camp prisoners were not being diverted by the German military.[5][lower-alpha 3] It is unclear to what extent the ICRC valued making an accurate report on Theresienstadt,[5] given that it had access to independent information confirming that prisoners were transported to Auschwitz and murdered there.[lower-alpha 4] The Danish government also pressured the Nazis to allow a visit, because of the Danish Jews who had been deported there in late 1943.[9] Theresienstadt, a hybrid concentration camp and ghetto, was used as a temporary holding camp for Jews whose final destination was extermination camps, especially Auschwitz. During the camp's existence, 33,000 prisoners died of starvation and illness.[10] The camp had been prepared for the visit by deporting 7,500 of its inhabitants to Auschwitz in order to ease overcrowding. Other prisoners had been forced to work on construction projects to superficially "beautify" the ghetto, including changing all the street names and building a fake school and other sham institutions that never operated. On the day of the visit, war veterans and other disabled Jews were forbidden from going out onto the streets.[11]

On 22 June 1944, Rossel left Berlin with Eigil Juel Hennigsen, head of the Danish Ministry of Health, and Frants Hvass, director general of the Danish Foreign Ministry.[11][12] The foreigners were chaperoned by several senior Schutzstaffel (SS) officials, most of them dressed in civilian clothes.[13][lower-alpha 5] The next day, they spent eight hours inside Theresienstadt, led on a predetermined path.[14][11] The visitors were only allowed to speak with Danish Jews and selected representatives, including Paul Eppstein, head of the Council of Elders.[9] Driven in a limousine by an SS officer posing as his driver,[15] Eppstein was forced to describe Theresienstadt as "a normal country town" of which he was "mayor",[9][16] and to give the visitors fabricated statistical data on the camp.[9] Rossel and the other representatives accepted the SS restrictions and made no attempt to investigate further, for example by investigating the stables, basements, and other unsuitable dwellings where most Theresienstadt prisoners were forced to live, or by asking questions of detainees.[12][17] Signs that Theresienstadt was not what the SS wanted to make it seem included a bruise underneath Eppstein's eye from when he had been beaten by Karl Rahm, the commandant of the camp, a few days earlier. During a brief opportunity to speak with Rossel alone, Eppstein tried to tip him off about the true situation. When asked about the ultimate fate of the prisoners, Eppstein said that there was "no way out" for them.[9][18] After the visit, the three foreigners were invited to dine with the Higher SS and Police Leader for the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Karl Hermann Frank.[14]

Rossel's report

All three visitors wrote reports, although as a condition of the visit, agreed not to distribute them. While the Hennigsen and Hvass reports "did not uncover the Nazi lies", they expressed sympathy for the Jews. Rossel's report was noted for its uncritical acceptance of Nazi propaganda.[lower-alpha 7] He stated that Jews were not deported from Theresienstadt; in fact, 68,000 people had already been deported and most murdered. Rossel also said that the camp was a town whose inhabitants had "the freedom to organise their administration as they see fit".[11][19] Rossel claimed that the residents were adequately nourished, and even better fed than non-Jews in the Protectorate.[22][lower-alpha 8] He wrote that the inhabitants were fashionably dressed and that their health was "carefully looked after"; life in the "town" was "almost normal".[24][25] It has been noted that he described the inhabitants of the ghetto as "Israelites" (French: Israélites) instead of "Jews" (French: Juifs).[2][26] Echoing Nazi propaganda which depicted a Judeo-Bolshevist conspiracy, Rossel described the ghetto as a "communist society" and Eppstein as a "Little Stalin".[16] At the end of his report, Rossel casts doubt on the Final Solution:

Our report will change nobody's opinion. Everyone is free to condemn the Reich's attitude toward the solution of the Jewish problem. However, if this report could contribute in some small measure to dispel the mystery surrounding the Theresienstadt ghetto we shall be satisfied.

— Rossel's report[27]

It is unclear what Rossel's true impressions of Theresienstadt were; he said that he was expected to file a factual report, not speculate about what the Nazis might be hiding from him.[3][28] Some authors have suggested that Rossel knew that the tour of Theresienstadt was a sham, but others disagree. Rossel took 36 photographs during his visit, attaching sixteen to his report. All but one were taken outside, and most portrayed festive scenes staged by the SS, such as the picture of children playing (above). It appears that Rossel was not allowed to photograph hospitals, sanitary installations, or work sites. According to Swiss historians Sébastien Farré and Yan Schubert, the photographs were viewed by the ICRC as neutral statements of fact, even though they were in fact highly staged, not accurately representing the daily life of Theresienstadt prisoners.[29] The ICRC did not release the report from its archives until 1992.[30]

Auschwitz visit

.jpg.webp)

According to Rossel, it was forbidden both by the Nazi regime and the Red Cross to visit Auschwitz. Nevertheless, Rossel became the first Swiss person to visit the camp and spoke to the commandant of Auschwitz I.[3][31] According to Czech historian Miroslav Kárný, the visit was on 29 September 1944, when more than 1,000 Theresienstadt prisoners were gassed and cremated at the nearby Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Rossel said that he did not notice any sign of mass murder.[25] The ICRC states that the visit took place two days earlier, on 27 September.[32] He later said that he did not see much of the camp, but did observe emaciated prisoners (Muselmänner) whose appearance greatly shocked him.[33]

Impact and assessment

Rossel's report is considered so important to the study of Theresienstadt and the Holocaust in the Czech lands that the full text was published in the first edition of Terezínské studie a dokumenty, an academic journal sponsored by the Terezín Initiative.[34]

According to Kárný, Rossel's report, particularly his insistence that Jews were not deported from Theresienstadt, had the effect of diminishing the credibility of the Vrba-Wetzler Report. Written by two Auschwitz escapees, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, the latter report accurately described the fate of Jews deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz—most were murdered.[19] Rossel's statement that Jews were not deported from Theresienstadt caused the ICRC to cancel a planned visit to the Theresienstadt family camp at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, to which Heinrich Himmler had already given his permission. Kárný and Israeli historian Otto Dov Kulka draw a direct connection between the report and the liquidation of the family camp in July, in which 6,500 people were murdered.[16][19][34] Rossel sent his photographs to Eberhard von Thadden, an official in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In a press conference, von Thadden showed copies of the photographs in an attempt to disprove reports on the Holocaust.[19]

The Red Cross' response to the Holocaust has been the subject of significant controversy and criticism.[lower-alpha 9] The choice of the young and inexperienced Rossel for the Theresienstadt visit has been interpreted as indicative of his organization's indifference to the "Jewish problem". His report has been described as "emblematic of the failure of the ICRC" to advocate for Jews during the Holocaust.[35][lower-alpha 10] Survivors accused the Red Cross representatives of seeing only what they wanted to see. One wrote that "a serious commission which really wanted to investigate our living conditions.... would have gone independently into the stables and attics".[17] However, an April 1945 report on Theresienstadt by a Red Cross delegation led by Otto Lehner was described as "even more unconscionable".[19]

A Visitor from the Living

In 1979, Claude Lanzmann interviewed Rossel as part of his Shoah documentary project. Instead of asking Rossel's permission and scheduling an interview, Lanzmann showed up on Rossel's doorstep with a film crew, intending to "[tease] out the structure of self-deception that Rossel has constructed in order to be able to live with himself".[39] In the interview, Rossel discusses both the Theresienstadt and Auschwitz visits. He blames the inaccuracy of his report on the Jews, who did not attempt to pass notes or covertly advise him that the visit was a sham. Rossel states that he therefore had no choice but to report what the SS allowed him to see.[2][3]

Lanzmann provides facts about the camp and the deceptive tactics used by the Germans, stating that the Jews were unable to tell the truth because they lived in fear of deportation to extermination camps.[3][2] Despite being informed about the true nature of the camp, Rossel did not express regret or embarrassment over the report. When asked if he stood behind his findings, Rossel answered that he did.[2][40] Pressed by Lanzmann, Rossel stated that he remembered the color of the Auschwitz commandant's eyes (blue) but nothing about Paul Eppstein.[39] Professor Brad Prager identified a sense of disconnection and othering between Rossel and the Jewish prisoners, which may have led to Rossel's inability to notice nonverbal cues that belied the SS' deception.[33] In 1997, Lanzmann contacted Rossel again for permission to use the interview in a documentary about the Red Cross visit, titled A Visitor from the Living (French: Un vivant qui passe). Rossel expressed concern that the interview portrayed him in a negative light.[2]

Later life

After World War II, Rossel left the Red Cross and tried to bury his wartime memories, not even telling his own children what he had seen.[3] Later in his life, he was reported to spend half of each year alone in the mountains.[41] In 1997, he was reported to be in poor health due to palsy.[2]

References

Notes

- ↑ The date of birth was calculated based on the information provided by Farré and Schubert, who cited his age as 27 in 1944.[1] Clines cited his age as 60 in 1979, meaning he could have been born in 1918 or 1919.[2]

- ↑ See The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland and Witold's Report.

- ↑ The operation to send food to concentration camp prisoners was much smaller in scale and lower priority than relief for prisoners of war.[5]

- ↑ Information about Jews deported to Auschwitz from Theresienstadt was published in the Jewish Chronicle in February 1944.[6] News of the first liquidation of the Theresienstadt family camp was relayed by the Polish underground state to the Polish government-in-exile and the Red Cross. The report was published in the official newspaper of the government-in-exile in early June, before Rossel's visit.[7] The information was also confirmed by the Vrba-Wetzler Report around the same time as Rossel's visit.[8]

- ↑ SS-Standartenführer Erwin Weinmann, high-ranking SD (Sicherheitsdienst) official and Holocaust perpetrator, SS-Sturmbannführer Rolf Günther, the assistant of Adolf Eichmann in the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), Eberhard von Thadden, external liaison of the RSHA, a German Red Cross representative named von Heydekampf, and the commandant of the concentration camp, SS-Obersturmführer Karl Rahm. Additional hosts not mentioned in Rossel's report were Eichmann's adjutant, SS-Hauptsturmführer Ernst Möhs, SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Günther, and SS-Obersturmführer Gerhard Günnel. The high ranks of the German escorts indicate the importance of the visit, and the overall program of deception about the Holocaust, to the Nazi regime.[14]

- ↑ According to one of the surviving children in this photo, Paul Rabinowitsch (1930–2009) from Denmark, third from left, the date the photo was taken was the only day he was allowed to eat his fill while imprisoned at Theresienstadt.[20]

- ↑

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: "... Rossel's report met the German authorities' most optimistic expectations. Uncritically accepting SS efforts at subterfuge, Rossel described Theresienstadt as a "final camp" from which Jews were no longer deported..."[16]

- Livia Rothkirchen: "In contrast to those of the Danish delegates, Rossel's report was phrased in positive terms, falling in line with German propaganda."[21]

- Lucy Dawidowicz: "[Rossel's] acceptance of everything he had seen... and everything he had been told... was total and complacent. The report which he prepared for his superiors in the Red Cross was exactly what the Germans had hoped for... a totally uncritical, even approving affirmation of their propaganda."[22]

- ↑ Rossel based this claim on his photographs, especially of children, and cursory inspection of canteens that had been purpose-built for the Red Cross visit and not regularly used.[20] While some people at Theresienstadt were reasonably well fed, others were starving, or had already starved to death.[23]

- ↑ As early as May 1944, the ICRC was criticized for its indifference to Jewish suffering and death—criticism that intensified after the end of the war, when the full extent of the Holocaust became undeniable. One defense to these allegations is that the Red Cross was trying to preserve its reputation as a neutral and impartial organization by not interfering with what was viewed as a German internal matter. The Red Cross also considered its primary focus to be prisoners of war whose countries had signed the Geneva Convention.[28]

- ↑ It has been noted that a similar visit to Drancy by Jacques de Morsier in May 1944 produced a "glowing" report.[36] Like Theresienstadt, Drancy was used a transit camp where Jews were held in harsh conditions before being sent to Auschwitz.[37][38]

Citations

- 1 2 3 Farré & Schubert 2009, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Clines 1999.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Maurice Rossel – Red Cross 1996.

- ↑ Farré & Schubert 2009, pp. 69–70.

- 1 2 3 Farré 2012, p. 1390.

- ↑ Fleming 2014, p. 199.

- ↑ Fleming 2014, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ Fleming 2014, p. 216.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Theresienstadt: Red Cross Visit 2018.

- ↑ Theresienstadt 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Stránský 2011.

- 1 2 Brenner 2009, p. 223.

- ↑ Dawidowicz 1975, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 Farré & Schubert 2009, p. 71.

- ↑ Brenner 2009, p. 228.

- 1 2 3 4 Blodig & White 2012, p. 181.

- 1 2 Prager 2008, p. 188.

- ↑ Dawidowicz 1975, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schur 1997.

- 1 2 Brenner 2009, p. 225.

- ↑ Rothkirchen 2006, p. 258.

- 1 2 Dawidowicz 1975, p. 138.

- ↑ Hájková 2013, pp. 510–511.

- ↑ Dawidowicz 1975, p. 139.

- 1 2 Kárný 1994.

- ↑ Blodig & White 2012, p. 184.

- ↑ Rothkirchen 2006, p. 259.

- 1 2 Farré & Schubert 2009, p. 72.

- ↑ Farré & Schubert 2009, p. 79.

- ↑ Sterling 2005, p. 28.

- ↑ Radio télévision suisse 1975.

- ↑ ICRC 2017.

- 1 2 Prager 2008, p. 190.

- 1 2 Kárný 1996.

- ↑ Farré & Schubert 2009, abstract.

- ↑ Farré & Schubert 2009, pp. 76, 80.

- ↑ Concentration Camps in France 2018.

- ↑ The Deportation of the Jews from France 2018.

- 1 2 Conlogue 2000.

- ↑ Prager 2008, p. 191.

- ↑ Simpson 2003, p. 100.

Print sources

- Blodig, Vojtěch; White, Joseph Robert (2012). Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Brenner, Hannelore (2009). The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope, and Survival in Theresienstadt. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780805242706.

- Dawidowicz, Lucy S. (1975). "Bleaching the Black Lie: The Case of Theresienstadt". Salmagundi (29): 125–140. JSTOR 40546857.

- Farré, Sébastien (31 December 2012). "The ICRC and the detainees in Nazi concentration camps (1942–1945)". International Committee of the Red Cross. 94 (888): 1381–1408. doi:10.1017/S1816383113000489. S2CID 146434201.

- Farré, Sébastien; Schubert, Yan (2009). "L'illusion de l'objectif" [The Illusion of the Objective]. Le Mouvement Social (in French). 227 (2): 65–83. doi:10.3917/lms.227.0065. S2CID 144792195.

- Fleming, Michael (2014). Auschwitz, the Allies and Censorship of the Holocaust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139917278.

- Hájková, Anna (2013). "Sexual Barter in Times of Genocide: Negotiating the Sexual Economy of the Theresienstadt Ghetto". Signs. 38 (3): 503–533. doi:10.1086/668607. S2CID 142859604.

- Kárný, Miroslav (1994). "Terezínský rodinný tábor v konečném řešení" [Theresienstadt family camp in the Final Solution]. In Brod, Toman; Kárný, Miroslav; Kárná, Margita (eds.). Terezínský rodinný tábor v Osvětimi-Birkenau: sborník z mezinárodní konference, Praha 7.-8. brězna 1994 [Theresienstadt family camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau: proceedings of the international conference, Prague 7–8 March 1994] (in Czech). Prague: Melantrich. ISBN 978-8070231937. OCLC 32002060.

- Kárný, Miroslav, ed. (1996). "Zpráva Maurice Rossela o prohlídce Terezína" [Maurice Rossel's report on the Theresienstadt tour]. Terezínské Studie a Dokumenty (in Czech): 188–206. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Prager, Brad (17 June 2008). "Interpreting the visible traces of Theresienstadt". Journal of Modern Jewish Studies. 7 (2): 175–194. doi:10.1080/14725880802124206. ISSN 1472-5886. S2CID 144375426.

- Rothkirchen, Livia (2006). The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: Facing the Holocaust. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803205024.

- Schur, Herbert (1997). "Review of Karny, Miroslav, ed., Terezinska pametni kniha". H-Net. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Simpson, John (2003). Simpson's World: Dispatches From The Front Lines. Miamax. ISBN 9781401300418.

- Sterling, Eric (2005). Life In The Ghettos During The Holocaust. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815608035.

Web sources

- Clines, Francis X. (24 June 1999). "A Holocaust Bloodhound Gently Tracks a Target". The New York Times. p. E00001. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Conlogue, Ray (6 November 2000). "Lest they forget, Shoah will remind them". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "The ICRC in WW II: The Holocaust". International Committee of the Red Cross. 15 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "Le CICR à Auschwitz". Radio télévision suisse (in French). 5 May 1975. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Stránský, Matěj (19 July 2011). "Embellishment and the visit of the International Committee of the Red Cross to Terezín". Terezín Initiative. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Maurice Rossel – Red Cross". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 1996. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Theresienstadt". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Theresienstadt: Red Cross Visit". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Concentration Camps in France". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "The Deportation of the Jews from France". Yad Vashem. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2018.