Mapuche medicine is the system of medical treatment historically used by the Mapuche people of southern Chile. It is essentially magical-religious in nature, believing disease to be caused by supernatural factors such as spells and curable by treatments based on rituals, thermal waters and herbs. Knowledge of medicinal herbs is one of the best-known elements of Mapuche medicine and is still used today.[1][2]

One of the most striking aspects of historical Mapuche medicine was the use of surgery as a treatment, which was developed to treat wounds and traumas suffered in the frequent battles between tribes. Fractures and dislocations of bones were treated by immobilising and covering the limbs with pastes and ointments made of medicinal herbs.[3] As in Europe, the practice of the bloodletting was also commonplace and used as a treatment for many conditions. In Mapuche culture, it was done by making small cuts with a very sharp stone called a "guincubue" to draw blood, then covering the cut with an astringent or herbal mix. Bloodletting was also used by parents on children to make them lighter, more agile and more capable of working and fighting, as it was thought that their blood was salty and heavy.[3]

Hygiene was very important in Mapuche life. They were very clean and tidy, bathing every day in nearby streams or rivers, regardless of weather conditions. The bark of the Quillaja tree, which is very common in the local area, was used as soap (and is still used today in some commercial beauty products).[2]

Historical context

The Mapuche people came about as the result of the mingling of two cultures: the Moluche people, from what today is Argentina's Pampa, with the indigenous inhabitants of the region between the Toltén and Bío Bío rivers in Chile. The Mapuche had no written language and their knowledge was transmitted orally. Most of their traditions and culture, including their medical knowledge, were documented for the first time by the European conquistadors.[4]

Different kind of healers

There were three main categories of doctors or healers in Mapuche medicine: the vileus, the ampiver and the machis.[3]

- Vileus:

- These were methodical doctors who believed that disease was caused by insects and worms. They worked to cure epidemic disease among the Mapuche which mainly arose after the arrival of the Spanish.

- Ampiver:

- These were empirical doctors with procedures based on observation, who used simple remedies and techniques. They knew how to take the blood pressure and make basic diagnoses. Their treatments were based mainly on the use of medicinal herbs.

- Lawentuchefe:

- They have great knowledge of healing through herbs and plants. They use this knowledge to help restore health when people suffer from different illnesses. The Lawentuchefe are not shamans and sometimes are confused with the Machi, but the Lawentuchefe do not have mystical knowledge. Their function is limited to herbalism and its applications to heal sickness. The state of the native forests have put the Lawentuchefes in a hard place because of the loss of the medical flora (lawen). This is also producing the loss of the Lawentuchefes in the communities.

- The machi (Mapuche shaman) was a combination of a priest and a healer. Mapuche people visited the machi only after other healers had been unable to cure their condition. They had rudimentary knowledge of human anatomy and, though unable to form a diagnosis based on disparate symptoms such as vomiting, fever or cramps, they were able to treat some monosymptomatic diseases like scabies, sciatica or gout with good results. They had a deep understanding of the benefits of hot springs and advised patients on which water source to help their illness. They successfully carried out minor surgery on fractures and small tumours and also had knowledge of medicinal plants, knowing specifically which plant, and which specific part of that plant, should be used to take best advantage of their medicinal qualities.

If a patient did not recover from any of these methods, the last resort was the performance of a magic ritual called "Machitún". Machis also served as advisors and oracles for their community.

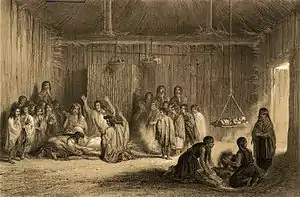

- Machitún

If a machi had tried all conventional treatments without success a machitún ceremony would be tried, where the machi communicates with the spiritual world in order to find a diagnosis and a cure. For the machitún, the machi places a bunch of laurel leaves with some canelo tree leaves in the centre in the corner of a small hut called a ruka [es:ruca |(ruca)], and prepares a goat for sacrifice there. Women sang mournful songs while the machi spread tobacco smoke through the room and got ready to sacrifice the animal. The goat's heart was cut out and placed it in the canelo leaves, and then the machi simulated penetrating the patient's abdomen in a search of the "magic poison". Finally, the machi played the cultrún and fell in a trance where the spirits would tell him how to treat the patient.[3] On occasion, the three kinds of doctors would meet to solve a problem in a meeting called a "Thauman".[3] Apart from the three kinds of doctors previously mentioned, there were two further kinds of surgeons. The cupove was a pathologist who would examine corpses to determine the disease and cause of death and the gutave was a surgeon expert at treating wounds, ulcers and many kinds of wounds.

Mapuche medicine today

There are several government programs today which aim to integrate traditional mapuche medicine with Western medicine. They look to incorporate the cultural aspects of Mapuche medicine into modern Western techniques and in this way facilitate bringing modern techniques into Mapuche communities. Examples include the "Programa de Salud Mapuche" (Mapuche Health Program) and the "Mesa Local (PROMAP)" (PROMAP Local Board). The latter aims specifically to incorporate Mapuche views on health and environmental issues into its work.[5]

References

- ↑ Mapuche herbal medicine {English} subtitles, Living Atlas Chile, retrieved December 07, 2013

- 1 2 {Spanish} Zúñiga S. Algunos aspectos de las costumbres y reseña del cuidado del niño entre los antiguos araucanos. Ars Médica. Revista de Estudios Médicos Humanísticos 2001; 141-150, retrieved December 5, 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cruz-Coke, Ricardo. Historia de la medicina chilena. Primera edición. Santiago de Chile: Andrés Bello, 1995, retrieved December 05, 2013

- ↑ Latcham, E. Ricardo. La organización social y creencias religiosas de los antiguos araucanos. Publicaciones del Museo de Etnología y Antropología de Chile. Tomo III. Imprenta Cervantes, Santiago, 1924

- ↑ Ministerio de salud de Chile redsalud.gov.cl , retrieved December 07, 2013