Manuel Torres | |

|---|---|

| 1st Colombian Chargé d'affaires to the United States | |

| In office June 19, 1822 – July 15, 1822 | |

| President | Simón Bolívar |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | José María Salazar |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 1762 Córdoba, Bourbon Spain |

| Died | (aged 59) Hamilton Village, Philadelphia, U.S. |

| Resting place | St. Mary's Church 39°56′44″N 75°08′54″W / 39.94563°N 75.14838°W |

| Signature | |

Manuel de Trujillo y Torres (November 1762 – July 15, 1822) was a Colombian publicist and diplomat. He is best known for being received as the first ambassador of Colombia by U.S. President James Monroe on June 19, 1822. This act represented the first U.S. recognition of a former Spanish colony's independence.

Born in Spain, he lived as a young adult in the colony of New Granada (present-day Colombia). After being implicated in a conspiracy against the monarchy he fled in 1794, arriving in the United States in 1796. From Philadelphia he spent the rest of his life advocating for independence of the Spanish colonies in the Americas. Working closely with newspaper editor William Duane he produced English- and Spanish-language articles, pamphlets and books.

During the Spanish American wars of independence he was a central figure in directing the work of revolutionary agents in North America, who frequently visited his home. In 1819 Torres was appointed a diplomat for Venezuela, which that year united with New Granada to form Gran Colombia. As chargé d'affaires he negotiated significant weapons purchases but failed to obtain public loans. Having laid the groundwork for the diplomatic recognition of Colombia, he died less than a month after achieving this goal. Though largely unknown today, he is remembered as an early proponent of Pan-Americanism.

Early life

Manuel Torres was born in the Spanish region of Córdoba in early November 1762.[lower-roman 1] His mother's family was from the city of Córdoba while his father's side was probably from nearby Baena. He was descended from the minor nobility on both sides of his family, a class with social stature but not necessarily wealth.[1]

In the spring of 1776 the young Torres sailed to Cuba with his maternal uncle Antonio Caballero y Góngora, who was consecrated there as bishop of Mérida in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (modern Mexico). Torres would later attribute his republican ideals to his uncle, a man of the Enlightenment who was an extensive collector of books, art, and coins. After Caballero y Góngora was promoted to archbishop of Santa Fé de Bogotá the family arrived in New Granada (modern Colombia) on June 29, 1778.[2]

At age 17 Torres began working for the secretariat of the Viceroyalty and for the royal treasury. In the following seven years he learned finance and was able to observe the political and social conflicts in New Grenada, including the Revolt of the Comuneros. This was also the time of the American Revolution, which Spain joined against Great Britain. Caballero y Góngora became viceroy in 1782 and ruled as a liberal modernizer.[3]

Torres went to France in early 1785 to study at the École Royale Militaire at Sorèze, where he spent about a year and half learning military science and mathematics. As lieutenant of engineers (Spanish: teniente de ingenerios) he probably aided Colonel Domingo Esquiaqui's survey and helped reorganize the colonial garrisons.[4] On presentation by the archbishop-viceroy, Torres was gifted land near Santa Marta by Charles IV and established a successful plantation, which he named San Carlos.[lower-roman 2] Torres married and at San Carlos had a daughter.[5][6]

He became involved with political liberals of Bogotá's criollo class (i.e., native New Granadians of European descent), joining a secret club led by Antonio Nariño where radical ideas were discussed freely. When in 1794 Nariño and other club members were implicated in a conspiracy against the Crown, Torres fled New Granada without his family. He first went to Curaçao, and in 1796 to Philadelphia,[7] then the capital of the United States.[8]

Arrival in Philadelphia

Spanish Americans heading north tended to go to Philadelphia, Baltimore or (French-controlled) New Orleans, centers of commercial relations with the colonies. Philadelphia in particular was a symbol of republican ideals, which may have attracted Torres. Its trade with the Spanish colonies was significant and the American Philosophical Society was the first learned society in the U.S. to nominate Spanish American members.[9] At St. Mary's Church he joined a cosmopolitan community of Roman Catholics, including many from Spanish and French America.[10]

Quick to make American contacts, Torres became close friends with William Duane, who became editor of the Philadelphia newspaper Aurora in 1798. The editor continually published Torres' views on Spanish American independence in the paper, whose contents would be copied by others. Torres translated Spanish pamphlets for Duane, and sometimes translated Duane's editorials to Spanish.[11] In Spanish America the purpose of this literature was to praise the United States as an example of independent representative government to be emulated; in the United States it was to increase support for the independence movements.[12]

Initially Torres was quite wealthy and received remittances from his wife, which helped him make important social connections. However, he had his money invested in risky merchant ventures; on one occasion he lost $40,000, on another $70,000—thus he was forced to live more modestly in later years.[13]

Three years after Torres' arrival, a "Spaniard in Philadelphia" wrote the pamphlet Reflexiones sobre el comercio de España con sus colonias en tiempo de guerra (released in English as Observations on the Commerce of Spain with her Colonies, in Time of War). The author, probably Torres, criticizes Spanish colonialism. In particular, Spain monopolized trade with the colonies to their detriment: during wartime the mother country could not supply the colonies with essential goods, and in peacetime the prices were too high. The author's solution is to implement a system of free trade in the Americas.[14] The pamphlet was reprinted in London by William Tatham.[15]

Torres' residence increased the attraction of Philadelphia for Spanish American revolutionaries. Torres probably met Francisco de Miranda (also exiled after a failed conspiracy) in 1805, shortly before Miranda's failed expedition to the Captaincy General of Venezuela, and he met with Simón Bolívar in 1806. The Spanish minister to the United States, Carlos Martínez de Irujo,[lower-roman 3] reported Torres' activity to his superiors.[16]

Coordinating revolutionaries

During the instability caused by Napoleon Bonaparte's conquest of Spain—the Peninsular War—the people of the colonies followed the model of Peninsular Spanish provinces by organizing juntas to govern in the absence of central rule. Advocates of independence, who called themselves Patriots, argued that sovereignty reverted to the people when there was no monarch. They clashed with the Royalists, who supported the authority of the Crown. Starting in 1810 the Patriot juntas successively declared independence, and Torres was their natural point of contact in the United States.[17]

Brokered weapons shipments

Although President James Madison's administration officially recognized no governments on either side, Patriot agents were permitted to seek weapons in the U.S., and American ports became bases for privateering. Torres acted as an intermediary between the newly arrived agents and influential Americans, such as introducing Juan Vicente Bolívar (Simón's brother) to wealthy banker Stephen Girard. Juan Vicente successfully purchased weapons for Venezuela, but was lost at sea on his return journey in 1811.[18]

Together with Telésforo de Orea from Venezuela, and Diego de Saavedra and Juan Pedro de Aguirre from Buenos Aires, Torres brokered a plan to purchase 20,000 muskets and bayonets from the U.S. government. Girard agreed to finance the plan on the joint credit of Buenos Aires and Venezuela, but Secretary of State James Monroe blocked it by refusing to reply. Saavedra and Aguirre managed to ship only 1,000 muskets to Buenos Aires, but by the end of 1811 Torres had helped Orea supply Venezuela with about 24,000 weapons. New purchasers continued to arrive, and the supplies were an important contribution while the revolutionaries were suffering many defeats.[19]

The new Spanish minister, Luís de Onís, covertly attempted to disrupt the weapons shipments. He became aware of the plan to purchase from the U.S. arsenal due to being informed by a postman. Onís reported on these subversive activities and his agents harassed suspected revolutionaries like Torres. Francisco Sarmiento and Miguel Cabral de Noroña, two associates of Onís, attempted to assassinate Torres in 1814—apparently on the minister's orders.[20] Due to his aid for the revolution, Torres' estate in Royalist-controlled New Granada was confiscated after his wife and daughter died.[21]

Public writing

Running out of money during this period, Torres sustained himself in part by teaching. With Louis Hargous he wrote an adaptation for both English- and Spanish-teaching of Nicolas Gouïn Dufief's Nature Displayed in Her Mode of Teaching Language to Man. The lengthy book's title page styles Torres and Hargous as "professors of general grammar"; in the introduction they argue the importance to Americans of studying Spanish literature.[22] Influential revised editions by Mariano Velázquez de la Cadena were published in New York (1825) and London (1826).[23]

Soon after Nature Displayed followed the 1812 pamphlet Manual de un Republicano para el uso de un Pueblo libre ("A Republican's Manual for the Use of a Free People"), which Torres probably wrote. Structured as a dialog, the anonymous pamphlet offers a defense of the U.S. system of government based on the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and argues it should be a model for Spanish America. The contents suggest the author is "a conservative partisan of Jeffersonian democracy".[24]

Besides Duane's Aurora, Torres sent news and opinion to Baptis Irvine's Baltimore Whig and New York Columbian, Jonathan Elliot's City of Washington Gazette, and Hezekiah Niles' Baltimore Weekly Register. He acquainted himself with notables such as Congressman Henry Clay, lawyer Henry Marie Brackenridge, Baltimore Postmaster John Stuart Skinner, Judge Theodorick Bland and Patent Office head William Thornton. Especially the support of Clay, who became a champion of Spanish American independence in Congress, permitted him to lobby many influential officials.[25]

Economic proposals

Torres' lobbying included domestic affairs; in February 1815, near the end of War of 1812 that had preoccupied the American public, he wrote two letters to President Madison describing a proposal for fiscal and financial reform.[27] This included an equal and direct tax on all property, which Torres considered more just; ultimately he calculated a $1 million budget surplus under his scheme and suggested gradual elimination of the national debt. In his December 5 message to Congress, Madison did propose two ideas that Torres had favored: the establishment of a second Bank of the United States and utilizing it to create a uniform national currency.[28]

The same year, Torres authored An Exposition of the Commerce of Spanish America; with some Observations upon its Importance to the United States.[29] This work, published in 1816, was the first inter-American handbook. Torres plays on Anglo-American rivalry by arguing for the importance of establishing American over British commercial interests in this critical region, just as revolutionary agents in Britain suggested the opposite.[30] Applying political economy, he observes that a country with a negative balance of trade—like the United States—needs a source of gold and silver specie—like South America—to stabilize its currency and economy. The political commentary is interwoven with practical advice to merchants, followed by conversion tables between currencies and units of measure.[31]

He momentarily returned to economics in April 1818. Through Clay, Torres suggested to Congress that he had discovered a new way to make revenue collection and spending more efficient, which he would reveal in detail if he was promised a share of the government's savings. The preliminary proposal was referred to the House Committee on Ways and Means, which declined to examine it for being too complex.[32]

Philadelphia junta

By 1816, Spanish American propagandists had solidified American public opinion in favor of the Patriots. However, the propaganda victories did not translate into practical success: the Royalists reconquered New Granada and Venezuela by May 1816. Pedro José Gual, who had come to the United States to represent those governments, instead worked with Torres on a plan to liberate New Spain. They were joined by a number of other agents to form a "junta" of their own, which included Orea, Mariano Montilla, José Rafael Revenga, Juan Germán Roscio from Venezuela, Miguel Santamaría from Mexico, as well as Vicente Pazos from Buenos Aires.[33]

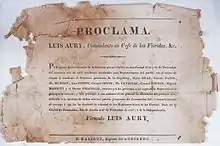

This Philadelphia junta surrounding Torres conspired in mid-1816 to invade a New Spanish port using ships commanded by French privateer Louis Aury. This plan failed because Aury's fleet was reduced to seven ships, making it unable to capture any major port. But the plotters were able to organize a force under the recently arrived General Francisco Xavier Mina (despite the obstructions of José Alvarez de Toledo, an acquaintance of Torres who was actually spying for Onís). The operation was funded by a group of merchants from Baltimore, where Torres traveled to oversee it. The exiled priest Servando Teresa de Mier had traveled to the U.S. with Mina, and became a good friend of Torres. He brought to Mexico with him two copies of Torres' Exposition and one of the Manual de un Republicano. The expedition sailed September 1816, but in just over a year Mina was captured and shot.[34]

Another of the agents to join the junta was Lino de Clemente, who in 1816 came to the United States as Venezuelan chargé d'affaires (a diplomat of the lowest rank). Torres became his secretary in Philadelphia. Clemente was one of the men who signed Gregor MacGregor's commission to seize Amelia Island off the coast of Florida, what became a political scandal known as the Amelia Island affair. All who had been involved became intolerable to Monroe.[35]

The Philadelphia junta effectively disbanded because of the event, which Simón Bolívar disavowed. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams refused any further communication with Clemente. Although Torres participated, he had discreetly avoided public involvement. (Privately he derided "Don Quixote" Aguirre and Pazos.)[36] In October 1818, Bolívar thus instructed Clemente to return home and to transfer his duties as chargé d'affaires to Torres.[37]

Diplomat for Colombia

Torres' appointment coincided with a turn in the wars of independence. Where before the situation had been dire, the Patriot forces under Bolívar began a campaign to liberate New Granada and achieved a famous victory at the Battle of Boyacá. When Torres received his diplomatic credentials he was authorized "to do in the United States everything possible to put an immediate end to the conflict in which the patriots of Venezuela are now engaged for their independence and liberty." Venezuela and New Granada united on December 17, 1819, to form the Republic of Colombia (a union called Gran Colombia by historians).[38]

Francisco Antonio Zea was first appointed Colombia's envoy to the United States but never went there; Torres was authorized to take over his duties on May 15, 1820, and thus formally empowered to negotiate for the republic. He would try to secure its independence by three methods: by purchasing weapons and other military supplies, by obtaining a loan, and by obtaining diplomatic recognition of its government.[39]

Weapons purchases

With the help of Samuel Douglas Forsyth, an American citizen sent from Venezuela by Bolívar, Torres was instructed to procure thirty thousand muskets on credit. This sum was not realistically available from private sources, in part due to the Panic of 1819. Torres did make substantial deals, especially with Philadelphia merchant Jacob Idler, who represented a network of business associates.[40]

In one such contract, signed April 4, 1819, Idler promised a total of $63,071.50 of supplies, including 4,023 muskets and 50 quintals[lower-roman 4] of gunpowder. After delivery Colombia was obliged to make payment in gold, silver or the tobacco produce of the Barinas province. More agreements on this model followed as merchants gained confidence with the news of successive Patriot victories. From December 1819 to April 1820 negotiated contracts worth $108,842.80 (equivalent to $3,156,000 in 2022[41]) and in the summer, Torres made a deal for the Colombian navy.[42]

Although Torres repeatedly wrote to his superiors about the great importance of maintaining Colombia's credit among American merchants, the government failed to make payment as agreed. In spite of this Torres was able to negotiate continued shipments, even with merchants who had unpaid claims.[43] After independence, such claims became a significant problem of U.S. relations with South America; Idler's estate would litigate them up to the end of the century. Nevertheless, Torres obtained from Idler 11,571 muskets, and other supplies such as shoes and uniforms. They arrived in Venezuela in 1820–1821 aboard the Wilmot and Endymion.[44]

In February 1820, Torres came to Washington to purchase twenty thousand muskets from the U.S. government—a source that could fill what he could not obtain from private merchants. Monroe delayed by responding that the Constitution prevented him from selling weapons without the consent of Congress, but his cabinet considered a missive from Torres. This missive argued for the sale by emphasizing the common interests of the American republics against the European monarchies. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun and Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson were supportive, and Torres had estimated the House of Representatives was in his favor. However, Secretary of State Adams emphatically spoke against what he considered a violation of American neutrality, causing the cabinet to unanimously decline the request in a meeting on March 29.[45]

The next day Adams explained his feelings to Monroe:[46]

I felt some distrust of everything proposed and desired by these South American gentlemen. Mr. Torres and Mr. Forsyth had pursued a different system from that of Lino Clemente and Vicente Pazos. Instead of bullying and insulting, their course had been to soothe and coax. But their object was evidently the same. The proposal of Torres was that while professing neutrality we should furnish actual warlike aid to South America.

Despite this skepticism, Adams trusted Torres to inform him on Spanish American affairs, perhaps because Torres was also strongly supportive of the United States. Torres made six repeat visits to Adams through February 19, 1821, without success.[47]

Attempted borrowing

Recognizing the financial difficulty the Colombian government was in, Torres attempted to borrow money in the United States on its behalf. Aided by a letter of introduction from Henry Clay, in the fall of 1819 he proposed a $500,000 loan (equivalent to $13,626,000 in 2022[41]) to Langdon Cheves, president of the Second Bank of the United States. It would be repaid with Colombian bullion, which the Bank was severely short of, within 18 months. When the Bank stated it had no authority to lend to foreign governments, Torres restated his proposal as a purchase of bullion. He also contacted Adams, who said the government had no objection and left it to the Bank directors' judgment, and gained Cheves' support. Despite continued negotiation this loan was never finalized—let alone Bolívar's bolder proposal for the Bank to take on the entirety of Venezuela's national debt in exchange for the Santa Ana de Mariquita silver mine in New Granada. Colombia had poor credit, and Torres believed the distressed Bank was actually unable to make the loan.[48]

To improve Colombia's financial reputation Torres circulated several public memorials, and he continued to seek loans from other sources. Idler introduced him to Philip Contteau, the American agent of the Dutch merchant firm Mees, Boer and Moens. On April 8, 1820, Torres and Contteau negotiated a loan of $4 million ($115,971,000) at eight percent interest. Colombia would maintain a state monopoly on Barinas tobacco, and would give sole control of the tobacco to Mees, Boer and Moens until the proceeds had repaid the loan. These terms were sent to Colombia and Holland for approval.[49]

Torres was instructed to borrow as much as $20 million ($579,853,000), an impossible request.[50] He did hope to build on his success by borrowing an additional $1 million ($28,993,000) with participation from the U.S. government. He made the request to Adams during the winter of 1820–1821, and obtained support from Monroe and Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford. However, like the weapons purchase, this proposal failed due to Adams' commitment to neutrality.[51]

The loan in its original form was approved by the Colombian government, but before the Dutch lenders could agree to it Barinas was recaptured by the Royalists. Without the source of tobacco on which repayment depended, the bankers rejected the loan.[52]

Thus, Torres was ultimately unable to borrow any money for Colombia. Historian Charles Bowman assessed Torres as a talented negotiator with an "exceptional knowledge of high finance", who failed due to circumstances beyond his control.[53]

Influence in pamphleteering

In June 1821, Mier returned to Philadelphia after escaping imprisonment in Havana, and moved into Torres' house.[lower-roman 5] (Another Spanish American agent, Vicente Rocafuerte, was already living there.)[54] Connected through Freemasonry, Torres became a father figure to Mier, signing his letters Tata T. He gradually drew Mier away from constitutional monarchism and toward the republican model of the United States. In doing so Torres tried to provide a political-philosophical basis for Mier's radicalism.[55] The pair encouraged Colombia to send a diplomat to Mexico, hoping to counter the rising monarchism there.[56] When Mier published his Memoria politíco-instructiva as well as a new edition of Bartolomé de Las Casas' Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, Torres paid the costs.[57]

Torres, Mier and Rocafuerte worked together to publish numerous articles over the next few months. The nature of their cooperation is disputed. Historian José de Onís mentions that "some Spanish American critics assert that Torres' works are generally regarded as having been written by Mier and Vicente Rocafuerte. This would be hard to verify."[58] But Charles Bowman gives the opposite interpretation: "It is likely that several of the works generally attributed to either Mier or Rocafuerte were actually from Torres' pen."[56]

In particular, Bowman believes a pamphlet bearing Mier's name, La América Española dividida en dos grande departamentos, Norte y Sur o sea Septentrional y Meridional, was actually Torres' work. Discussing political organization after the revolution, the author suggests a "Spanish America Divided in Two Grand Departments, North and South, or Septentrional and Meridional." Bowman bases this attribution on a moderation uncommon for Mier, and the use of statistics Mier would not have known. Torres' motive for publishing it under Mier's name would have been to avoid controversy and thus protect his influence with Adams.[59]

During this period Torres also became friends with Richard W. Meade, a Philadelphia merchant who had in 1820 returned from imprisonment in Spain. He had a claim against the Spanish government that the Adams–Onís Treaty required him to collect from the U.S. government instead. Meade was a pewholder of St. Mary's Church, like Torres. Through the diplomat, Mier and Meade began working together in a controversy surrounding the parish priest, William Hogan, who had been excommunicated. Torres did not get publicly involved in the battle of pamphlets; Mier left Philadelphia for Mexico in September 1821, traveling with a Colombian passport Torres had issued him.[60]

Diplomatic recognition

_-_Carta_IX_-_Guerras_de_independencia_en_Colombia%252C_1821-1823.jpg.webp)

On the same day the U.S. Senate voted to ratify the Adams–Onís Treaty, February 19, 1821, Torres met with Adams. The next day he formally requested the recognition of Colombia "as a free and independent nation, a sister republic". He expected that first the United States would take possession of the new territory, while in the meantime Colombia gained increasing military control over its own, and that recognition would soon follow.[61]

Torres suffered a three-month illness in late 1821 but on November 30 wrote to Adams reporting the latest developments in Colombia. He glorified its achievement of near-total military victory, the extent of its population and territory, and its potential for commerce:[62]

She also unites by prolonged canals, two oceans which nature has separated; and by her proximity to the United States and to Europe, appears to have been destined by the Author of Nature as the centre and empire of the human family.

The purpose of these boasts was to underscore the importance of the U.S. being the first to recognize its independence, to which Torres added warnings about the unstable politics of Mexico and Peru. The letter received significant publicity because of its extensive information and ambitious statement of Colombia's importance.[63]

President Monroe noted the success of Colombia and the other former colonies in his December 3 message to Congress, a signal that recognition was imminent. Torres wrote letters to Adams on December 30 and January 2 reporting Colombia's new constitution, a sign the republic was stable. He hoped to go to Washington to state the case for recognition in person, but was prevented by illness and poverty. The House of Representatives asked the administration on January 30 to report on the state of South America. Colombia's de facto independence as a republic, and the conclusion of Adams' treaty with Spain, encouraged the hesitant administration that the time was ripe for recognition. During this same period, the Colombian government was starting to see the prospect of recognition as hopeless.[64]

Torres' health declined intermittently over the winter; his weakening disposition was attributed to asthma and severe overwork.[65] "If I could move to a good climate where there were no books, paper, or pen and where I could speak of politics in a word, ... with my little garden and a horse to carry me about, perhaps I could convalesce", he wrote to Mier.[66] But in March, Monroe reported to the House that the Spanish American governments had "a claim to recognition by other powers which ought not to be resisted." The formerly reluctant Adams dismissed a protest by Spanish minister Joaquín de Anduaga by calling the recognition "the mere acknowledgment of existing facts". By May 4, the House and Senate had sent Monroe resolutions in support of recognition and an appropriation to put this into effect; this news was greatly celebrated in Colombia.[67] Pedro José Gual, now the Colombian secretary of state and foreign relations, wrote to Bolívar that Torres deserved sole credit for the achievement.[68]

The question remained when to send ministers and whom to recognize first. At this time, Torres was the only authorized agent in the United States for any of the Patriot governments.[69] It was Adams' suggestion that Torres should be received as chargé d'affaires immediately, with the United States reciprocating after other diplomats arrived; Monroe agreed to thus formalize his existing relationship with Torres. The chargé was invited on May 23 but delayed by his poor health. Nevertheless, he insisted on traveling to Washington.[70]

At 1 p.m. on June 19, Torres was received at the White House by Adams and Monroe. The weakened Torres told them of the importance of recognition to Colombia, and wept when the President said how satisfied he was for Torres to be received as its first representative. Indeed, he was the first representative from any Spanish American government. On leaving the short meeting, Torres gave Adams a print of the Colombian constitution.[71]

Before Torres departed Washington, Adams visited him on June 21; he promised Adams to work for equal tariffs on American and European goods in Colombia, and predicted José María Salazar would be sent to the U.S. as permanent diplomat. Adams published a satisfied announcement in the National Intelligencer.[72]

Death

In rapidly declining health, Torres returned to Hamiltonville, now in West Philadelphia, where that spring he had purchased a new home. Duane was with him when he died there at 2 p.m. on July 15, 1822, at age 59.[73]

On July 17, the funeral procession began from Meade's house, which was joined by Commodore Daniels of the Colombian navy and prominent citizens. The procession went to St. Mary's, where the requiem mass was held by Father Hogan and Torres was buried with military honors. Ships in the harbor held their flags at half-mast. [74] This highly unusual display of honor was not only because Torres was well-liked, but also because he was the first foreign diplomat to die in the United States.[75] An obituary named him "the Franklin of South America".[76]

Duane and Meade were the executors of his estate.[77] Not yet aware of his death, the Colombian government appointed him consul-general and (as he had predicted) sent Salazar as envoy to succeed him.[78]

Legacy

Sources for Torres' life include his voluminous correspondence,[79] his published writing, newspaper articles, and Adams and Duane's memoirs. His long exile from Colombia has tended to obscure him in diplomatic history compared to his contemporaries;[80] indeed his grave site was forgotten until rediscovered by historian Charles Lyon Chandler in 1924.[81]

R. Dana Skinner called him "the first panamericanist" that year.[82] During the U.S. Sesquicentennial Exposition in 1926, a plaque was placed at St. Mary's that honors him as "the first Latin American diplomatic representative in the United States of America." It was a gift "from the government of Colombia and Philadelphian descendants of his friends", including Duane's great-great-grandson. The ceremony was attended by Colombian minister Enrique Olaya, who held him up as a model for cooperation of the peoples of the New World.[83]

Responding to an accusation by Spanish writer J. E. Casariego that Torres was a traitor to his native Spain, Nicolás García Samudio in 1941 called him a patriot, even the originator of the Monroe Doctrine[84]—though that specific claim has been met skeptically.[lower-roman 6] A 1946 article suggested Torres had not been given a large enough place in Colombian diplomatic histories, and likewise praised him as a "precursor of pan-Americanism".[85]

In the United States, Torres is given modest attention in general diplomatic histories,[86] but his importance is promoted by historians of Spanish American agents. In the judgment of José de Onís, Torres was "the most successful of all the Spanish American agents".[12] Charles H. Bowman Jr. wrote a master's thesis and a series of articles about Torres in the 1960s and 1970s. To celebrate the 150th anniversary of U.S.–Latin American relations in 1972, the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States held a session in Philadelphia because it was the home of Manuel Torres.[87]

However, Emily García documented that in 2016 Torres was obscure even to the archivists of St. Mary's, where the plaque still hangs. That he is mostly unknown today, despite being celebrated in his time and with the plaque, is for her illustrative that "Latinos inhabit a paradoxical position in the larger U.S. national imaginary."[88] Her book chapter analyzes him as the embodiment of a culture bridge that existed between Philadelphia and Spanish America: while he helped spread U.S. ideals to the south, he also brought Spanish influences to the north. This dual nature is characteristic of Torres' life and thinking.[89]

Works

- ——— (1799). Reflexiones sobre el comercio de España con sus colonias en tiempo de guerra [Observations on the Commerce of Spain with her Colonies, in Time of War] (anonymous pamphlet). Philadelphia. English translation 1800.[90]

- ———; Hargous, L. (1811). Dufief's Nature Displayed in Her Mode of Teaching Language to Man: or, A New and Infallible Method of Acquiring a Language, in the Shortest Time Possible, Deduced from the Analysis of the Human Mind, and Consequently Suited to Every Capacity (in English and Spanish). Philadelphia: T. & G. Palmer. hdl:2027/nyp.33433075921019.

- ——— (1812). Manual de un Republicano para el uso de un Pueblo libre [A Republican's Manual for the Use of a Free People] (anonymous pamphlet). Philadelphia: T. Palmer.

- ——— (1815). An Exposition of the Commerce of Spanish America; with some Observations upon its Importance to the United States. To which Are Added, a Correct Analysis of the Monies, Weights, and Measures of Spain, France, and the United States; and of the Weights and Measures of England: with Tables of their Reciprocal Reductions; and of the Exchange between the United States, England, France, Holland, Hamburg; and between England, Spain, France, and the Several States of the Union. Philadelphia: G. Palmer (published 1816). hdl:2027/hvd.hn3mpv.

Notes

- ↑ Some sources, including the plaque at St. Mary's, give 1764 instead. Bowman (1971b, p. 440 n. 5) derives the 1762 birthday from two letters Torres wrote Mier in 1821: on October 31 he said he was aged 58, on November 18 he said he was 59.

- ↑ Duane (1826, p. 609) described what he heard of the ruined plantation in 1823, suggesting what it used to be like:

I enquired; and learned there was not a vestige of a habitation: the forests which [Torres] had felled, and the gardens laid out and cultivated under his own eye, in which were collected and collecting all the riches of the botanical regions; the avenues of cotton trees and oranges, the groves of foreign firs on the lofty peaks, and the palms in the valleys, had lost their order and disposition[.]

- ↑ The seat of government moved to Washington in 1800, but the Spanish ministers continued to reside in Philadelphia.

- ↑ The quintal is 100 Spanish pounds, in modern units approximately 101.5 pounds (46.0 kg).

- ↑ Domínguez Michael (2004, p. 600) briefly mentions Torres having a wife and children with him, "su esposa Mariquita y sus hijos e hijas", but no other authors do.

- ↑ As articulated by Whitaker (1954, p. 27):

The argument is quite unconvincing, if only because there is no reason to believe that a foreign envoy (and an unrecognized one, at that) could have played any important part in persuading Adams and Monroe to adopt an idea which had been anticipated by many persons in the United States, including statesmen of the first rank, during the past decade.

Citations

- ↑ Bowman (1971b), pp. 416–417.

- ↑ Bowman (1971b), pp. 417–418.

- ↑ Bowman (1971b), pp. 423–424.

- ↑ Bowman (1971b), pp. 429–431.

- ↑ Duane (1826), p. 608.

- ↑ Bowman (1971b), pp. 435–437.

- ↑ 1797 is given by Onís (1952, p. 34); but for 1796 see Bemis (1939), p. 21; Hernández de Alba (1946), p. 368; Bowman (1970), p. 26.

- ↑ Bowman (1971b), pp. 434–439.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Warren (2004), pp. 344–347.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 Onís (1952), p. 34.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Morrison (1922), p. 84.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), p. 34.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), p. 39.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Vilar (2001), pp. 245–249.

- ↑ Onís (1952, p. 35) writes Torres' authorship "is possible"; Bowman (1970, pp. 41–42) writes he "probably" wrote it and infers Torres' Jeffersonianism.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), p. 43.

- ↑ Torres to Madison, February 11, 1815, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, James Madison Papers, hdl:loc.mss/mjm.17_0026_0028

; Torres to Madison, February 25, 1815, James Madison Papers, hdl:loc.mss/mjm.17_0157_0159

; Torres to Madison, February 25, 1815, James Madison Papers, hdl:loc.mss/mjm.17_0157_0159 .

. - ↑ Bowman (1971a), pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Onís (1952, pp. 34–35), refers to this book as two separate works.

- ↑ Blaufarb (2007), p. 759.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 42–44.

- ↑ Bowman (1971a), p. 109.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 44–48.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 48–49.

- ↑ "Debemos tener presente lo que expuso Mr. Clay acerca de la incapacidad del Dn. Quixote Aguirre, y aún de Pazos." Torres to Juan Germán Roscio, April 12, 1819, in Hernández de Alba (1946), p. 394.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Bowman (1968), p. 236.

- ↑ Hernández Delfino (2015), pp. 70–72.

- ↑ Bowman (1968), p. 237.

- 1 2 Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- ↑ Bowman (1968), pp. 237–240.

- ↑ Bowman (1968), pp. 240–242.

- ↑ Grummond (1954), p. 135.

- ↑ Bowman (1968), pp. 242–245.

- ↑ Adams (1874–1877), V, p. 51.

- ↑ Bowman (1968), pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Bowman (1971a), pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Bowman (1971a), p. 111.

- ↑ Bowman (1971a), p. 145.

- ↑ Bowman (1971a), pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Bowman (1971a), pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Bowman (1971a), p. 114.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 18.

- ↑ Domínguez Michael (2004), pp. 597–610.

- 1 2 Bowman (1969), p. 19.

- ↑ Vogeley (2011), p. 86.

- ↑ Onís (1952), p. 35.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 20–22; for more on this controversy see Warren (2004).

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 23.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 24–26.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 26–27; Bowman (1970), p. 53.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 30.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 27–29.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 29.

- ↑ Robertson (1915), p. 189.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 31.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 32.

- ↑ Bowman (1968), p. 245; Bowman (1970), p. 53.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 38.

- ↑ New York Evening Post, "The Franklin of South America", 1822, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Simon Gratz collection. For analysis of this comparison see Bowman (1969), pp. 33–34; García (2016), pp. 84–86

- ↑ Bowman (1976a), p. 111.

- ↑ Bowman (1969), p. 33.

- ↑ Much of it preserved in Colombian archives, see Bowman (1976b).

- ↑ Vilar (2001), p. 243 n. 7.

- ↑ Avenius (1967), p. 180.

- ↑ Skinner, R. Dana (1924). "Torres, the First Panamericanist". The Commonwealth. New York. Cited in García Samudio (1941, p. 484).

- ↑ "In Honor of the Patriot" (1926), pp. 950–953.

- ↑ García Samudio (1941, pp. 480–482), also citing the early argument by Chandler (1914, p. 517).

- ↑ Hernández de Alba (1946), p. 367.

- ↑ E.g., Robertson (1915), pp. 188–191; Bemis (1939), pp. 21–22, p. 83; Randall (1992), pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Jova (1983), p. 49.

- ↑ García (2016), p. 72.

- ↑ García (2016), pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Bowman (1970), p. 29 n. 23: "A copy of the Spanish edition with a manuscript note concerning typographical errors is to be found among the Duane pamphlets in the Library of Congress."

Bibliography

- Adams, John Quincy (1874–1877). Charles Francis Adams (ed.). Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, comprising portions of his diary from 1795 to 1848. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. OL 1535782W.

- Avenius, Sheldon H. Jr. (1967). "Charles Lyon Chandler: A Forgotten Man of Inter-American Cultural Relations". Journal of Inter-American Studies. 9 (2): 169–183. doi:10.2307/165091.

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg (April 1939). "Early Diplomatic Missions from Buenos Aires to the United States, 1811–1824" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. 49 (1): 11–101.

- Blaufarb, Rafe (June 2007). "The Western Question: The Geopolitics of Latin American Independence". American Historical Review. 112 (3): 742–763. doi:10.1086/ahr.112.3.742.

- Bowman, Charles H. Jr. (May 1968). "The Activities of Manuel Torres As Purchasing Agent, 1820–1821". Hispanic American Historical Review. 48 (2): 234–246. doi:10.2307/2510745.

- ——— (March 1969). "Manuel Torres in Philadelphia and the Recognition of Colombian Independence, 1821–1822". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 80 (1): 17–38. JSTOR 44210719.

- ——— (January 1970). "Manuel Torres, a Spanish American Patriot in Philadelphia, 1796–1822". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 94 (1): 26–53.

- ——— (June 1971a). "Financial Plans and Operations of Manuel Torres in Philadelphia". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 82 (2): 106–116. JSTOR 44210765.

- ——— (September 1971b). "Antonio Caballero y Góngora y Manuel Torres: La Cultura en la Nueva Granada". Boletín de Historia y Antigüedades (in Spanish). 58: 413–452.

- ———, ed. (December 1976a). "Correspondence of William Duane in Two Archives in Bogotá". Revista de Historia de América (82): 111–125. JSTOR 20139242.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ——— (December 1976b). "Calendar of Correspondence of Colombian Agents in the United States, 1816–1824". Revista de Historia de América (82): 139–157. JSTOR 20139244.

- Chandler, Charles Lyon (July 1914). "The Pan American Origin of the Monroe Doctrine". American Journal of International Law. 8 (3): 515–519. doi:10.2307/2187493.

- Domínguez Michael, Christopher (2004). Vida de Fray Servando (in Spanish). Mexico, D.F.: Ediciones Era.

- Duane, William (1826). A Visit to Colombia in the Years 1822 and 1823. Philadelphia: T.H. Palmer. OL 24760573M.

- García Samudio, Nicolás (1941). "La misíon de don Manuel Torres en Washington y los orígenes suramericanos de la doctrina Monroe". Boletín de Historia y Antigüedades (in Spanish). 28: 474–484.

- Grummond, Jane Lucas de (May 1954). "The Jacob Idler Claims Against Venezuela 1817–1890". Hispanic American Historical Review. 34 (2): 131–157. doi:10.2307/2509321.

- García, Emily (2016). "On the Borders of Independence: Manuel Torres and Spanish American Independence in Filadelphia". In Lazo, Rodrigo; Alemán, Jesse (eds.). The Latino Nineteenth Century: Archival Encounters in American Literary History. New York: New York University Press. pp. 71–88. ISBN 9781479855872.

- Hernández de Alba, Guillermo (December 1946). "Origen de la Doctrina Panamericana de la Confederacion: Don Manuel Torres, precursor del panamericanismo". Revista de Historia de América (in Spanish) (22): 367–398. JSTOR 20137520.

- Hernández Delfino, Carlos (2015). "Manuel Torres y las relaciones internacionales de Hispanoamérica". Boletín de la Academia Nacional de la Historia (in Spanish). 98 (391): 65–96.

- "In Honor of the Patriot, Don Manuel Torres". Bulletin of the Pan American Union. LX (10): 950–957. October 1926.

- Jova, Joseph J. (March–April 1983). "Art as a Tool of Diplomacy". Americas. 35 (2): 49.

- Morrison, A.J. (April 1922). "Colonel Tatham and Other Virginia Engineers". William and Mary Quarterly. Second Series. II (2): 81–84. doi:10.2307/1921435.

- Onís, José de (1952). The United States as Seen by Spanish American Writers (1776–1890). New York: Hispanic Institute in the United States. hdl:2027/uc1.b3626361.

- Randall, Stephen J. (1992). Colombia and the United States: Hegemony and Interdependence. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Robertson, William Spence (September 1915). "The First Legations of the United States in Latin America". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 2 (2): 183–212. doi:10.2307/1887061. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t79s1m699. JSTOR 1887061.

- Vilar, Mar (2001). "Un gramático anglista poco conocido: Manuel Torres, adaptador en 1811 en los Estados Unidos para la enseñanza del español a anglófonos del método 'Nature Displayed' de N.G. Dufief y colaborador de los lingüistas y lexicógrafos Hargous y Velázquez de la Cadena" (PDF). ES: Revista de Filología Inglesa (in Spanish). 23: 241–252.

- Vogeley, Nancy (2011). The Bookrunner: A History of Inter-American Relations—Print, Politics, and Commerce in the United States and Mexico, 1800–1830. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. JSTOR 41507683.

- Whitaker, Arthur P. (1954). The Western Hemisphere Idea: Its Rise and Decline. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Warren, Richard A. (October 2004). "Displaced 'Pan-Americans' and the Transformation of the Catholic Church of Philadelphia, 1789–1850". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 128 (4): 343–366.