Manuel Rodríguez Lozano | |

|---|---|

Rodríguez Lozano c. 1928 | |

| Born | December 4, 1896 |

| Died | March 27, 1971 (aged 74) |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Known for | painting |

| Movement | Mexican muralism |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

Manuel Rodríguez Lozano (December 4, 1896 – March 27, 1971) was a Mexican painter, known for his “melancholy” depiction of Mexico rather than the more dominant political or festive one of the Mexican muralism movement. This is especially true of his “white stage” which is marked by cold colors and tragic scenes focusing on human figures which are skeletal or ghost-like. His work influenced Mexican films such as La perla.

Life

Manuel Rodríguez Lozano was born in Mexico City, with his birth year placed between 1894 and 1897.[1][2][3] He was from a wealthy family, the son of Manuel Z. Rodríguez and Sara Lozano, who were interested in art and music and entertained visitors such as poet Amado Nervo.[3]

When he was eleven, he enlisted in the military service and took examinations to enter the diplomatic corps. However, he eventually abandoned both.[2][3] He then began to paint on his own in 1910,[2][4] moving on to attend the Academy of San Carlos under teachers such as Germán Gedovius and Alfredo Ramos Martínez. However, he left the school after a short time for unknown reasons.[3]

In 1913, Rodríguez Lozano married Carmen Mondragón, later known as Nahui Ollín. The two met at a dance and she became smitten with him. At first he was not interested but her father, General Manuel Mondragón, was a powerful man politically, and this changed the artist’s mind.[2][4] However, shortly after the marriage, General Mondragón was involved in the Decena tragica and the assassination of Francisco I. Madero, which forced the entire family into exile into Europe for eight years.[2][3][4] At first the couple lived in Paris, but with the outbreak of World War I, the family moved to Spain.[3] His time in Europe, especially Paris, put him in touch with avant garde artists such as Matisse, Braque and Picasso as well as writers such as André Salmon, Jean Cassou and Andre Lothe, who influenced his art.[2] However, his relationship with Nahui Ollín was problematic. She did not like his bohemian friends and accused him of being a homosexual. The couple had a child in 1914, but the infant died shortly after birth. Rodríguez Lozano stated that his wife smothered the child but her family denied it. The couple separated when Rodríguez Lozano returned to Mexico in 1921.[3][4]

In the early 1920s, Rodríguez Lozano had an amorous relationship with Abraham Ángel, who was also his student. Ángel died in 1924 from a cocaine overdose, which may have been intentionally suicidal.[2][4]

In 1928, he began a relationship with Antonieta Rivas Mercado. She was in love with him, ignoring his relationships with men. She did much for his career but the two never became sexual. She committed suicide in 1931.[2][4][5] The deaths of his child, Ángel, and Rivas Mercado, along with his incarceration in 1940, left scars and made his art darker.[6]

Rodríguez Lozano died in Mexico City on March 27, 1971, from heart failure. He was buried at the Panteón de Dolores in Mexico City.[3][7]

Career

After Rodríguez Lozano returned from Europe to Mexico in 1921, he exhibited his work at the Department of Fine Arts and in San Carlos.[2] The following year, out of necessity, he accepted a position as a drawing teacher for elementary schools, introducing a technique developed by Adolfo Best Maugard .[2][3]

In 1923, Roberto Montenegro introduced Manuel to Francisco Sergio Iturbe, who became his patron and protector.[3]

During the early 1920s, he began to teach two students, Abraham Ángel and Julio Castellanos, as well as promote their artwork.[3] In 1925, the three traveled to Argentina to present at the Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes. The three then traveled to Paris to exhibit at the Cercle Paris Amirique Latine.[2][3][7] Along with these two he had two other important students, Tebo and Nefero.[1]

In 1928, he began a relationship with Antonieta Rivas Mercado, the daughter of a prominent architect. The two founded the Ulises Theater, the headquarters for the Contemporáneos group and an important meeting place for artists and intellectuals such as Salvador Novo, Isabela Corona and Celestino Gorostiza. The organization not only put on plays for which Rodríguez did set design, it also edited and published books such as Dama de corazones by Xavier Villaurrutia and Los hombres que disperse la danza by Andrés Henestrosa. At the request of Carlos Chavez, Rodríguez Lozano convinced Antonieta to help form council to found a Mexican symphony orchestra, and he founded El ballet de la paloma azul.[2][3][7]

From 1932 to 1933, he painted Los tableros de la muerte, commissioned by Iturbe, and in 1935 he finished Il Verdaccio, one of his most important works.[3]

In 1940, Rodríguez Lozano was appointed as the director of the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, and then invited artists such as Diego Rivera, Antonio M. Ruíz, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Luis Ortiz Monasterio and Jesús Guerrero Galván to work with the school.[2][3] As director, he founded the magazines Artes Plásticas and promoted meetings outside his house which was attended by artists and intellectuals such as Alfonso Reyes, Dolores del Río, Rodolfo Usigli and Nelson Rockefeller as a center of intellectual life in Mexico City.[3] However, there were internal political struggles and his tenure was ended with an accusation of theft against him. The school received a request to lend engravings by Albrecht Dürer and Guido Reno for the 400th anniversary of the founding of the Colegio de San Nicolás in Michoacán. Rodríguez Lozano requested the works but then they disappeared and he was held responsible for the theft, imprisoned in Lecumberri prison .[3][8] During his time in prison he painted a mural and worked on materials that were later published in a book. After four months he was released and renounced everything he had before. The engraving reappeared without explanations in 1966.[3][7]

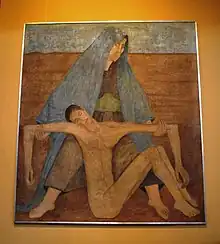

During his career, the artist created two murals. The first was while he was in Lecumberri, called Piedad en el desierto, notable as the start of his “white” stage of artistic production. This work was later moved to the Palacio de Bellas Artes and restored in 1967.[3] In 1945 he painted the mural El holocaust, in Iturbe’s house, now the Isabel la Católica building.[3][8] For just these two murals some critics have stated that he should be considered among the best of Mexico’s muralists.[1][9]

In 1948, he was invited by the University of Paris and the Musée de l'Homme to exhibit at the Musée de l'Orangerie.[3]

He stopped painting in the 1950s although there is a portrait of Alfonso Reyes from 1960.[8] In 1960, he published an anthology of his essay as Pensamiento y pintura.[2][7]

The National Museum of Mexican Art has thirty of his paintings.[2]

Rodríguez Lozano’s work was recognized with a retrospective as part of Mexico City’s 1968 Summer Olympics,[3] as well as another posthumously in 2011 at the Museo Nacional de Arte. In 2011, a book titled Manuel Rodríguez Lozano. Pensamiento y pintura 1922-1958 was published, based on the work by the artist.[8] He was a member of the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana.[10]

Artistry

Rodríguez Lozano began his career at the time that Mexican muralism was being established as the main artistic movement in the country. José Vasconcelos invited the artist to participate in the government projects being sponsored but the Rodríguez Lozano refused because he did not believe that art should be used for political messages.[7][9] His depictions of subjects did not follow the movement either, preferring more poetic interpretations, and for much of his career did not heavily rely on Mexican archetypes, believing that his work was “Mexican” no matter what.[2][7] His work does show some influence from European art movements, from the time he spent on the continent, especially from the work of Giorgio de Chirico and Pablo Picasso. However he does not follow any of these trends faithfully either, leading his work to be characterized as Cubist and Surrealist .[4][8] While this led to rejection of work by contemporary art critic Luis Cardoza y Aragón, later critics such as Raquel Tibol and Berta Taracena have been more positive, both noting that his work depicted a melancholy Mexico rather than a festive one.[8] While his subject matter was generally related to life in Mexico, especially its suffering, he also did a number of portraits such as those of Jaime Torres Bodet, Daniel Cosío Villegas and Rodolfo Usigli, with one done of Antonieta Rivas Mercado after her death.[6]

Rodríguez Lozano’s work is divided into three distinct periods. The first focused on Mexican archetypes and lasted from 1922 to 1934. These figures were often life-sized or monumental, with solid and thick forms focusing on folkloric content with embellished realism. These compositions are simplistic, with restricted but rich color to evoke nostalgia, but without being purely decorative.[2][3] The second stage is called the monumental stage, lasting from 1935 to 1939. These works depicted everyday life in Mexico, with exaggerated proportions and gigantic figures for poetic effect. These figures included prostitutes, laborers, and people of poor neighborhoods. Some are nudes and some seem to look off into the horizon. Towards the end of this period, his colors become paler.[3] Although he began some of the tendencies earlier, his last stage, known as the “white stage” is marked by the creation of the mural Piedad en el desierto while the artist was imprisoned in Lecumberri. In this stage, colors pale to cold lilacs, blues, grays and light pinks, revolving around white with the only dark and profound colors appearing in night skies.[2][3] Scenes here are tragic, with dramatic expressions of anguish, desolation and desperation, expressing both misery and grandeur.[3][7][9] Works still focus on human figures, but these evolve from robust to elongated, sublime and almost skeletal or ghost-like, with forms styled to their fundamentals.[2][3] Often these figures are androgynous or mix elements of male and female.[8] Mexican archetypal elements still appear, such as the use of the rebozo to indicate pain and suffering. This use later influenced cinema productions such as the film La perla by Emilio Fernández.[9] During this stage Rodríguez produced over thirty paintings and two murals, lasting until he retired from painting in the mid 1950s.[2][3]

References

- 1 2 3 Fabienne Bradu (November 2011). "Manuel Rodríguez Lozano y Antonieta Rivas Mercado ¿Qué se ama cuando se ama?". Nueva Época (in Spanish). Mexico City: UNAM. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Guillermo Tovar de Teresa (1996). Repertory of Artists in Mexico: Plastic and Decorative Arts. Vol. III. Mexico City: Grupo Financiero Bancomer. p. 198. ISBN 968-6258-56-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Vision de México y sus Artistas (in Spanish and English). Vol. I. Mexico City: Qualitas. 2001. pp. 136–139. ISBN 968-5005-58-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Braulio Peralta (July 30, 2011). "Las tres muertes de Rodríguez Lozano" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Milenio. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ↑ Pável Granados (September 24, 2011). "Manuel Rodríguez Lozano en el MUNAL" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Siempre! magazine. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- 1 2 Adrián Figueroa. "Muestra el Munal 118 obras de Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, un artista "dolorosamente templado"" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Crónica. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tesoros del Registro Civil Salón de la Plástica Mexicana [Treasures of the Civil Registry Salón de la Plástica Mexicana] (in Spanish). Mexico: Government of Mexico City and CONACULTA. 2012. pp. 197–198.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Judith Amador Tello (August 25, 2011). "Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, el pintor del dolor del pueblo" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Proceso magazine. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Judith Amador Tello (October 11, 2011). "El mural escondido de Rodríguez Lozano" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Proceso magazine. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Lista de miembros". Salón de la Plástica Mexicana. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.