Manuel Alberti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Committee member of the Primera Junta | |

| In office 25 May 1810 – 11 January 1811 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 May 1763 Buenos Aires, Viceroyalty of Peru, Spanish Empire |

| Died | 31 January 1811 (aged 47) Buenos Aires, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Alma mater | National University of Córdoba |

| Occupation | Priest |

| Signature |  |

Manuel Máximiliano Alberti (28 May 1763 – 31 January 1811) was an Argentine priest from Buenos Aires when the city was part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He had a curacy at Maldonado, Uruguay during the British invasions of the River Plate, and returned to Buenos Aires in time to take part in the May Revolution of 1810. He was chosen as one of the seven members of the Primera Junta, considered the first national government of Argentina. He supported most of the proposals of Mariano Moreno and worked at the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres newspaper. The internal disputes of the Junta had a negative effect on his health, and he died of a heart attack in 1811.[1]

Biography

Early life

Manuel Alberti Marín was born in Buenos Aires on 28 May 1763 to Antonio Alberti and Juana Agustina Marín. He was baptized on the following 1 June at the Concepción parish; his godparents were Juan Javier Dogan and Isabel de Soria y Santa Cruz. He had three brothers, Isidoro, Manuel Silvestre and Félix, and three sisters, Casimira, Juana María and María Clotilde. The Alberti family became benefactor of the House of Spiritual Works of Buenos Aires by donating them a land plot so it could move its headquarters.[2]

He made his first studies at the Real Colegio de San Carlos in February 1777, graduating in philosophy, logic, physics and metaphysics. He studied with Hipólito Vieytes, and ended his secondary education on 17 February 1779. He moved to Córdoba the following year, to get university studies of theology at the National University of Córdoba. Despite a brief return to Buenos Aires during his second year because of health problems, he could finish all the syllabus. He got his doctorate in theology and physics on 16 July 1785. He got his degree at the Church of the Company from interim provost Fray Pedro Gaitán.[3]

He received the presbyterate in the first months of 1786, and was appointed for the Concepción parish, the same one where he was baptized. He also worked at the aforementioned House of Spiritual Works of Buenos Aires. He got the curacy of Magdalena on 12 September 1790, but resigned a year later because of health problems. He returned in 1793, and resigned definitively on 21 February 1794. After this, he moved to Maldonado. There are few historical records of his activities in those curacies.[4]

The territory was briefly captured by British forces when Britain invaded the River Plate during the Napoleonic Wars. Alberti provided medical aid to wounded Spanish soldiers and conducted Catholic funerals for military casualties; he also secretly wrote letters to nearby Spanish authorities containing details about the British military disposition in the city.[5] When his letters were discovered by the British occupational authorities, he was arrested and imprisoned. However, Alberti was subsequently released by British Army officer John Jaime Backhouse, who permitted a restoration of Catholic religious practices in the city under military escort.[6] The British would eventually be defeated by Spanish forces led by Santiago de Liniers and forced to surrender, resulting in them evacuating the region.

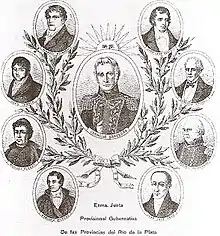

Primera Junta

He returned to Buenos Aires in 1808, and got the curacy of San Benito de Palermo. This was supposed to be a new jurisdiction split from the one of San Nicolás de Bari, but such change was never effected, so he was actually in charge of both.[6] He became involved with politics as well, joining the groups of Miguel de Azcuénaga and Nicolás Rodríguez Peña. Those groups sought to generate great political and social changes, and would lead to the May Revolution. He was selected to take part in the open cabildo celebrated on 22 May to decide the fate of Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros, as well as other twenty-seven ecclesiastics. He was among the nineteen that voted for the removal of the viceroy, supporting the proposal of Cornelio Saavedra.[6] He also supported Juan Nepomuceno Solá and Ramón Vieytes, who proposed the calling of deputies from the other cities of the viceroyalty.[7]

His brother Manuel Silvestre Alberti signed the popular petition formulated on 25 May that aimed to draft the composition of the Primera Junta that would replace Cisneros in power.[8] On that day Alberti moved to Azcuénaga's house and from it he observed the events in the plaza, along with many other patriots gathered there. He was there when he learned that he was chosen as a member of the new Junta.[8] The reasons of Alberti's inclusion in the Junta are unclear, as with all its members. A common accepted theory considers it to be a balance between Carlotists and Alzaguists,[9] and Alberti in particular may have been elected to serve as chaplain of the government.[10]

In the Junta, Alberti was aligned with most of the reformist proposals of Mariano Moreno, as well as Juan Larrea and Juan José Castelli.[11] He signed most of the rulings that shaped the new political system, such as those related to popular sovereignty, representative and republican principles, separation of powers, publicity of the government actions, freedom of speech and the bases of political federalism. However, he did not support the actions of the Junta that contradicted his religious formation, regardless of the context.[12] He refused to sign the death penalty for Santiago de Liniers, captured after the defeat of his counter-revolution. He signed the harsh commands given to Castelli for the first Upper Peru campaign, but noticing next to his signature that he made an exception with the articles involving capital punishment.[8] He was also concerned by the role of the church in the new political system and headed a dispute against the Cabildo about it. He considered that the Cabildo should not have any authority over the Junta in ecclesiastic topics, to prevent the former abuses of the absolutist governments.[13]

Manuel Alberti worked in journalism as well, at the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres newspaper created by the Junta. The ruling that created this newspaper gave Alberti the duty of selecting the news reports to publish. This duty was exclusive of Alberti and not shared with the other members of the Junta. Some historians also consider that Alberti may be the real author of the newspaper's editorials, as they were not signed and the style is not similar to other reports by Mariano Moreno, who is usually considered the author.[14]

The first conflict between Alberti and Moreno was caused by the arrival of Gregorio Funes, dean of Córdoba with similar ideas to those of Cornelio Saavedra, president of the Junta. Moreno was keeping an internal dispute with Saavedra, and expected Alberti to write against Funes. He did not, and Moreno made harsh comments about it.[15] Alberti would be further distanced from Moreno when the Junta voted for the incorporation of the deputies from other cities into the Junta. At first, both of them opposed the proposal, but Alberti ultimately voted accepting it,[8] stating that he did so just out of political convenience. The Primera Junta was thus turned into the Junta Grande. Mariano Moreno, left in a minority group, resigned.[15]

The inclusion of new deputies increased disputes within the Junta. He opposed both Saavedra and Funes, albeit in a more moderate manner than Moreno. Those fights affected his health, and he had a mild heart attack on 28 January 1811.[16] Fearing for his life, he wrote his will and received the Anointing of the Sick. Three days later he had another strong disagreement with Funes, and had another heart attack when he was returning to his house. He was buried in the cemetery of San Nicolás de Bari, as requested in his will.[16] The death certificate states that he had not been given last rites because his unanticipated death did not allow for time.[16] Alberti was the first member of the Primera Junta to die.[17]

Commemoration

All members of the Junta Grande assisted to Alberti's funeral, even his political enemy Gregorio Funes.[16] Domingo Matheu was the most affected one by his death, to the point of crying for it.[16] Alberti was replaced in the Junta by Nicolás Rodríguez Peña, a decided morenist. Saavedra and Funes did not like him, but with the social commotion generated by Alberti's death, they did not oppose his nomination.[16]

Alberti requested in his will to avoid pageantry or complex funerals, and bequeathed his properties (house, farm, furniture, slaves, clothing, books, etc.) to his siblings Juana María, Matilde, Casimira and Manuel Silvestre. His personal diaries are kept, but with some parts of them being lost due to poor keeping.[16] Still, his personal bibliography was used by historians to reconstruct his influences and ideological background. It included many works of theology, studies of the Bible, scholastic theologists and juridical studies. Alberti's remains were lost when the chapel was demolished to make way for an expansion of 9 de Julio Avenue.[16]

The government of Buenos Aires named a street in his honor in 1822. In 1910, during the Argentina Centennial, a statue of him was erected in Barrancas de Belgrano, a neighborhood at the north of Buenos Aires. The district of Manuel Alberti, in Buenos Aires Province, is also named after him.

See also

Bibliography

- Balmaceda, Daniel (2010). Historias de Corceles y de Acero. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3180-5.

- Luna, Félix (2003). La independencia argentina y americana (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Planeta. ISBN 950-49-1110-2.

- National Academy of History of Argentina (2010). Revolución en el Plata (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Emece. ISBN 978-950-04-3258-0.

References

- ↑ Durán, Juan Guillermo (August 2011). "Presbítero Manuel Maximiliano Alberti (1763–1811): párroco de San Nicolás de Bari y vocal de la Primera Junta. En el bicentenario de su muerte" (PDF). Revista Teología (in Spanish). Universidad Católica Argentina. XLVII (105): 193–210. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ↑ National... pp. 3031

- ↑ National... p. 31

- ↑ National... p. 32

- ↑ Balmaceda, p. 38

- 1 2 3 National... p. 33

- ↑ National... pp. 33–34

- 1 2 3 4 Balmaceda, p. 39

- ↑ Luna, p. 39

- ↑ National... pp. 34–35

- ↑ National... p. 35

- ↑ National... p. 36

- ↑ National... pp. 35–36

- ↑ National... pp. 36–37

- 1 2 National... p. 37

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Balmaceda, p. 40

- ↑ National... p. 38

External links

- Educar – Argentina (in Spanish)