Louth Park Abbey was a Cistercian abbey in Lincolnshire, England. It was founded in 1139 by the Bishop Alexander of Lincoln as a daughter-house of Fountains Abbey, Yorkshire.[1]

Founding

The founder originally offered the monks a site on the Isle of Haverholme, but they were unhappy with the agricultural potential, and it was given to the order of Gilbert of Sempringham, who settled there in 1139.[2] Alexander of Lincoln then gave the Cistercians a site within his own park at Louth instead.[2] The original abbey charter was transcribed into Priory Book of Alvingham and reads, in part:

Alexander, by the grace of God, bishop to all his successors sendeth greetings... I, by the counsaile of my clergie and assent of my whole chapter of the churche of Saynte Marie at Linkholne, am disposed to found an abbey of mookes of St, Marie, of the Fountaynes, accordinge to the order of the blessed St. Benedict and custoomes of (Cistercians) in my woode, namely, in my Parke on the south syde of my towne called Lowthe, which parke I have graunted wholie and free from all terrene service..."[2]

The first monks to settle at the abbey site were headed by Abbot Gervase of Louth.[2]

Abbey and grounds

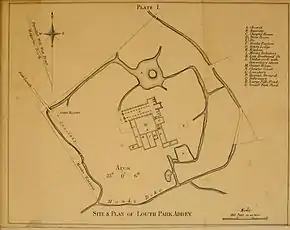

The abbey was situated on an elevated area of ground, of around 23 acres, south of the River Lud.[3] The river was used by the abbey to turn the wheel of the grain mill that had been given to them by Alexander of Lincoln 'to ever more to possess', but was too distant for general water needs, or to supply their fishponds.[2] To solve this, the monks dug a ditch to bring water from the springs of Ashwell and St. Helen's at Louth to the abbey grounds.[4] The ditch reached the abbey from the east and then divided into east and west channels around its edges, effectively forming a moat.[2] The western channel circled around northwards and rejoined the main channel. To the east, the water was sent into two fishponds, one 'of great size', was still full of water, and stocked with fish, in the late 1800s.[2] Now known as 'Monks' Dyke', although substantially altered, the main ditch from the Louth springs still survives today.[4]

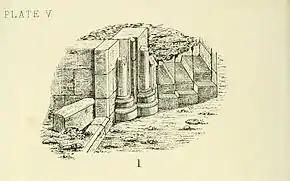

The earliest abbey buildings, built by the monks after the foundation, were plain and unadorned, as preferred by the Cistercians, in the Transitional Norman style.[2] Fragments of decorative stone sculptures, incorporated from the abbey ruins into a 17th-century garden folly in Louth, have been dated to between 1140 and 1160,[5] while an arch, now part of a nearby church, and believed to have been part of the abbey, also dates to a similar period.[6] Building at the east side of the Cloister Court, including a Chapter-house and Calefactory, were built around 1246, during the time of Abbot Richard of Dunholm,[2] who raised the house "from dust and ashes".[7]

By 1291, the abbey housed 66 monks and 91 conversi, or lay brothers.[2] During the Black Death of the 1340s 'many monks' died, including the Abbot Dom Walter de Louth, who was succeeded by Dom Richard de Lincoln on the day of his death.[8]

A plan drawn up in 1873 from historic records and site visits suggests that at its most developed the abbey included a church, sacristy, chapter house, store rooms, monk's parlour, Abbot's lodge, kitchen, monk's refectory, Lay brother's refectory, undercroft with dormitory above, guest house, cloister court and lavatory as one complex, with a separate infirmary building and gate house. In the grounds, in addition to the two fish ponds, was a burial ground.[3]

The internal length of the church at the abbey was 256 ft by 6 ft making it 70 ft longer than the nearby church of St. James Church at Louth, and the nave, was 61 feet wide, only 11 feet less than Lincoln Cathedral.[3] Its walls were 7 foot wide and constructed from Lincoln stone, sandstone and chalk.[3]

The le Vavasour manor

In the early 1340s, the 'depressed condition' of the abbey led to Edward III taking it over and appointing Thomas Wake to manage it until all debts had been discharged.[7] Around this time, the Abbot, Walter de Louth, was summoned to Cockerington by Sir Henry le Vavasour, who was in failing health, to hear his confession.[9] Le Vavasour, 'either spontaneously, or under pressure from the Abbot', agreed to leave the abbey his Cockerington manor.[9] But this endowment, 'instead of proving a relief to the monks in their embarrassments, only brought about further litigation'[7] and was remembered in the abbey chronicles as an event that led the Abbot to endure 'great harassment' before he died.[8]

Le Vavasour wanted to move to the abbey, in the interests of his health, possibly on the recommendation of his physician.[9] The Abbot agreed and sent a covered cart to collect him, later stating that le Vavasour was 'fit enough to walk to his chamber and demand constant attention'.[9] Deeds for the endowment were, nonetheless, drawn up, with representatives of both parties involved in ensuring the interests of abbey, and le Vavasour's wishes, were met.[9] This included a provision for le Vavasour's wife Constance to receive 100 marks per annum and, after her death, for her and le Vavasour's son to receive 20 marks per annum for his lifetime.[9] Le Vavasour also required the abbey to admit ten more monks to the monastery, and celebrate divine service for his soul for evermore.[7] Countermeasures were also included in the document in the case of the family objecting to the endowment or 'bad faith' on the part of the abbey.[9]

Le Vavasour's health declined and, on the day before his death, he appointed John de Brinkhill, and others, as executors of the endowment deed.[7] His wife, Constance, was present at the signing of the document, but was not aware of its contents, which she assumed were 'to her advantage'.[7] By the time the endowment was revealed the monks had taken possession of Cockerington manor, and Constance began a series of public claims about the validity of the gift,[10] including that her husband had not been 'of sound mind', or even deceased,[9] when he was said to have affixed his seal to the deed.[7] Her claims were examined at an inquisition, where an important witness was le Vavasour's servant Alice, who testified that not only was Constance present in the room but that she had handed her husband the seal.[9][10] The inquisition eventually found deed valid and the abbey maintained possession of the manor.[7]

At the end of the decade the Black Death reached the abbey, and 'many of the monks of Louth Park died', including the Abbot, Dom Walter of Louth.[8] He was buried beside Sir Henry le Vavasour, in front of the high altar of the abbey church.[8]

Endowments and extortions

The endowment received several benefactions, notably from Ralph, Earl of Chester, Hugh and Lambert de Scotney, and Hugh of Bayeux. William of Frieston, Hugh of Scotney, Gilbert of Ormsby, Eudo of Gilbert and Ivo of Strubby, were some of those recorded as having given the abbey lands in Tetney, Elkington, Aby and Messingham, in a charter of confirmation of the order's possessions granted by Henry III in 1224, and confirmed by Edward III in 1336.[2]

Towards the end of the 12th century one of the endowments made to the abbey of land outside Lincolnshire reveals their skill as ironworkers.[2] Sir Water de Abbetoft gave the monks some his woods at Birley, in Brampton, Derbyshire, with rights to ironstone, and beech and elm for fuel, a bloomery, or iron smelting furnace, and a forge.[2][11]

King John is recorded as having stayed the night, on 18 January 1201, while on a tour of Lincolnshire.[12] During his brief reign from 6 April 1199 until his death in 1216, he's said to have extorted 1,680 marks (£1,120) from the abbey.[7]

Dissolution and later history

The abbey's fortunes declined and there were only ten monks with Abbot George Walker when it was dissolved in the Act of Suppression on 8 September 1536.[2][7] The Abbot was given a pension and the monks had £4. 6s. 8d. to divide between them, and an additional 20 shillings each to purchase secular clothes.[7] One of the monks, William Moreland, alias Borroby,[13] or Borrowby, later recalled that, at first, 'they lived for a while as near as they might to their old monastery', only venturing out to attend church in Louth or talk with one another.[7] Moreland was having breakfast with his fellow former monk Robert Hert when they heard the alarm that signalled the start of the Lincolnshire Rising.[7] Moreland joined the protestors and was later put to death as a traitor.[7]

The abbey site was initially granted to Thomas Burgh, 1st Baron Burgh, for his lifetime, but was transferred to Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, two years later, in gratitude, by Henry VIII, for Suffolk's part in repressing the Lincolnshire Rising, which began at St. James Church in Louth in October 1536.[2] Elizabeth I gave the park to Sir Henry Stanley, and his wife Margaret, around 1570.[14]

In 1643, Sir Charles Bolles, a resident of Louth, raised a 'hastily-got-up soldiery' for the Royalist cause in the English Civil War. Fighting took place in, and around the town and, at its end 'Three strangers, being souldgeres, was slain at a skirmish at Lowth, and was buryed'.[15] Human remains, found during archaeological visits to the abbey during the late 1800s,[16] in 'a little space surrounded by a ditch' were believed to date from the Civil War as two cannonballs, from that era, were found with the bodies.[3]

Ruins and relics

A 1726 engraving, The North East View of Louth Park Abbey near Louth in the County of Lincoln, by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, shows the remains of a number of stone walls standing.[17] A similar view is presented in an engraving of the abbey ruins from 1770 in Robert S. Bayley's Notitiæ Ludæ, Or Notices of Louth.[18]

In 1818, Thomas Espin designed the new town hall in Louth and was permitted to take the materials from the former building, in lieu of his fee, to construct his house The Priory, in the town.[19] He was also allowed to take 'sculptural fragments' from the abbey ruins, which he combined with other medieval stonework, to create a folly beside his garden lake.[5] One fragment is a Romananesque head with curled hair, an indication of a moustache and beard, possibly crowned with a diadem.[5] The others are capitals, the topmost member of a column (or pilaster), and are variously decorated, often with leaves of different kinds.[5]

In 1850, an arch was found in nearby field, and incorporated in St. Margaret's Church, Keddington, as part of the pipe organ chamber.[6] Featuring rolls, hollows and Dog-tooth decoration, and dating to the Early English Period of the 12th century, it is believed to have originally been part of the abbey.[6]

In 1873, the owner of the abbey site, Mr. W. Allison, 'disinterred' the ruins, finding the stone coffins of two former abbots buried in the chapter house and 'many other relics of great interest'.[20] The Louth Museum holds one of these 'Abbots' coffins',[21] theirs dating from a burial at the abbey in the 14th century.[22]

The third All Hallows' Church at Wold Newton was built in 1140 and survived until 1643.[23] In the 1880s, 'curious bases and capitals of columns' were found in the walls of the local manor house and, while possibly belonging to the third church, were also considered, because of 'their enormous proportions and design' to have come from the abbey.[23] They were last known to be in the garden at the manor house.[23] A heavy stone block, beneath a window, in St. Andrew's church, Stewton, is thought to be a keystone of a rib-vault from the ruins of either the abbey or Legbourne Priory.[24]

The surviving remains on the site today comprise extensive earthworks, and, of the church, the ruined north and south chancel walls, and the base of a nave pillar.[25] They are a Grade I listed building.[26]

References

- ↑ David M. Smith, ‘Alexander (d. 1148)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Venables, Edward (1873). "Louth Park Abbey". Reports and papers of the architectural and archaeological societies of the counties of Lincoln and Northampton. Lincoln: James Williamson. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Trollope, Edward (1873). "The Architectural remains of Louth Park Abbey". Reports and papers of the architectural and archaeological societies of the counties of Lincoln and Northampton. Lincoln: James Williamson. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- 1 2 Historic England. "Monks Dyke (354511)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Russo, Thomas E. (2008). "Priory Hotel, Louth, Lincolnshire". Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland. Department of Digital Humanities, King's College London. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Nikolaus Pevsner; John Harris; Nicholas Antram (January 1989). Lincolnshire. Yale University Press. pp. 410–411. ISBN 978-0-300-09620-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "The abbey of Louth Park". Houses of Cistercian monks. Victoria County History. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Rosemay Horrox (15 October 1994). The Black Death. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3498-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sandra Raban (1982). Mortmain Legislation and the English Church, 1279-1500. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-521-24233-2.

- 1 2 Janet Burton; Janet E. Burton; Julie Kerr (2011). The Cistercians in the Middle Ages. Boydell Press. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-1-84383-667-4.

- ↑ Maxwell Ayrton; Arnold Silcock (2003). Wrought Iron and Its Decorative Use. Courier Dover Publications. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-486-42326-5.

- ↑ Archaeologia Or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity. Soc. 1829. p. 131.

- ↑ Ecclesiastical History Society (1972). Schism, Heresy and Religious Protest: Papers Read at the Tenth Summer Meeting and the Eleventh Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society. CUP Archive. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-521-08486-4.

- ↑ Mary Saunders (1836). Lincolnshire in 1836: displayed in a series of engravings, with accompanying descriptions [by M. Saunders]. John Saunders. p. 151.

- ↑ Robert Slater Bayley (1834). Notitiæ Ludæ, Or Notices of Louth. [By Robert S. Bayley. With Plates.]. The Author. pp. 77–78.

- ↑ "AN OLD ABBEY". The Tablet. 13 February 1892. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "Engravings by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck. Buck's Views". Heaton's of Tisbury. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ Robert Slater BAYLEY (1834). Notitiæ Ludæ, Or Notices of Louth. [By Robert S. Bayley. With Plates.]. The Author. p. 134.

- ↑ "History". The Priory Hotel. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ The Church. The Hull Packet and East Riding Times (Hull, England), Friday, 27 June 1873; Issue 4616.

- ↑ "Ludalinks Gallery". Louth Museum. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "History is right on your doorstep". Grimsby Telegraph. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 Wright, William Maurice. "A Short History". Wold Newron Archives. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ Pevsner/Harris (1989) pp. 717–718.

- ↑ Historic England. "Louth Abbey (354511)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "LOUTH ABBEY RUINS (1063050)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

Further reading

- Venables, E.; Maddison, A. R., eds. (1891). Chronicon Abbatie de Parco Lude. Lincolnshire Record Society. Vol. 1. Horncastle: Lincolnshire Record Society.