The Lordship of Denbigh was a marcher lordship in North Wales created by Edward I in 1284 and granted to the Earl of Lincoln. It was centred on the borough of Denbigh and Denbigh Castle. The lordship was held successively by several of England's most prominent aristocratic families in the 14th and 15th centuries. Title to the lordship was disputed for much of the second half of the 14th century between two powerful noble families: the Mortimer Earls of March and the Montagu Earls of Salisbury. Eventually, the lordship returned to the crown when Edward, Duke of York, who had inherited the lordship through his grandmother, acceded to the throne in 1461 as Edward IV. In 1563, Elizabeth I revived the lordship and granted it to her favourite Lord Robert Dudley, later becoming the Earl of Leicester. Leicester mortgaged it to raise money and the lordship was finally returned to the crown when Elizabeth redeemed the mortgage in 1592/3.

The crown disposed of much of the lordship's lands over the following centuries. Although the lordship still technically exists, with the monarch as its holder, its remaining lands, chiefly common land (for example, on Denbigh moors), are vested in the Crown Estate. The Crown Estate also conducts the annual Lordship of Denbigh Estray Court which continues to exercise a historic jurisdiction over the area's stray sheep.

Origins

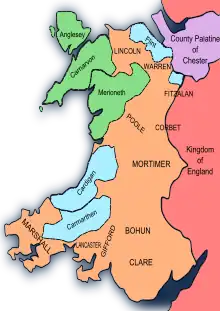

Prior to the creation of the lordship of Denbigh in 1284, the territory of the lordship was part of the Principality of Gwynedd. Since the Norman invasion in the 11th century, Wales had been divided between the native Welsh principalities and lordships in the north and centre of the country, and the Marcher lordships of Anglo-Norman origin in the south and south-east.

The Marcher lords exercised effectively independent power in their territories and had only a nominal feudal allegiance to the king of England. During the 13th century, the Welsh princes of Gwynedd, taking the title Prince of Wales, had built up their power to such an extent that the English king, Edward I, launched a war of conquest of north Wales between 1277 and 1283.

Following the final defeat of the last Prince of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, in 1282, Edward I distributed the territories of the former principality between himself and his supporters. The majority of the territory became a personal fief of the crown and, in 1301, was granted to his son, the future Edward II, as a revived Principality of Wales. The rest was granted to nobles that had supported him in the conquest. In 1284, Edward granted the cantreds of Rhos and Rhufuniog and the commote of Dinmael to Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln as the lordship of Denbigh.[1] The Earl was one of the closest counsellors of Edward I and had played a leading role in the campaigns in Wales of 1277 and 1282.[2]

History

Marcher lordship

As a marcher lordship, the lordship of Denbigh was not a part of the Kingdom of England and was a de facto independent territory, subject to feudal allegiance to the crown. As with the other marcher lordships created by Edward I in North Wales, it was, in fact, held as a tenant-in-chief of the Principality of Wales rather than directly from the king.[3] The administration was conducted by a steward who presided over a Curia Baronis and the territory was divided for administrative purposes into the five commotes of Ceinmerch, Isaled, Uwchaled, Isdulas, and Uwchdulas.[4] The Curia Baronis, with two Courts Leet, had wide jurisdiction over all criminal and civil matters.[4]

Following the grant of the lordship to him, the Earl of Lincoln founded the borough of Denbigh and constructed Denbigh Castle as the centre of the lordship.[2] He also began a programme of moving the native Welsh out of key areas and giving their land to English settlers.[5] Several discrete English communities were formed within the lordship, concentrated in the two commotes of Ceinmerch and Isaled, where, by 1334, 10,000 acres were occupied by the settlers.[5]

The Earl of Lincoln died in 1311, leaving his daughter, Alice, as his sole heir. The lordship therefore passed to Alice's husband, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, but returned to the crown after Thomas was executed in 1322 for leading a revolt against Edward II.[6] The lordship then came into the hands of Edward II's favourite, Hugh Despenser.[7] Following Despenser's fall from power in 1326, it was granted to the powerful Earl of March, Roger Mortimer who, in turn, forfeited it for treason in 1330.[7] In 1331, Edward III granted it to William Montagu, 1st Earl of Salisbury as a reward for his assistance in overthrowing Mortimer.[7] To make good his title to the lordship, Montagu had to pay substantial compensation to Lancaster's widow and the Despenser family.[7] In 1354, Mortimer's grandson succeeded, in a court case against Montagu's son, in having the lordship returned to his family.[7] The basis of the decision was that the Montagus did not have lawful title to the lordship following the reversal of the 1330 attainder of Mortimer's grandfather.[7] The Montagus refused to accept the decision and continued to fight, unsuccessfully, for the return of the lordship until at least 1397.[7] The contest between the Montagus and the Mortimers over the lordship of Denbigh became one of the most celebrated aristocratic land disputes of the 14th century.[8]

From the Mortimer Earls of March the lordship passed in 1425 to Richard, Duke of York, the Yorkist claimant to the crown during the Wars of the Roses.[6] Richard inherited it, through his mother, Anne Mortimer, when the last Mortimer Earl of March died.[6] On Richard's death in 1460, his son, Edward of York, inherited the lordship and his father's claim to the throne. When he became king in 1461, as Edward IV, the lordship of Denbigh was united with the crown.[6]

Merger with the Crown and revival

Although it became merged with the crown in 1461, it retained its identity as a Lordship outside of the Kingdom of England until, as with the rest of Wales, it was effectively incorporated into the kingdom by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542. The Laws in Wales Acts ended the special position of the Marcher Lords and effectively abolished their independent jurisdictions. However, the baronial courts were allowed to maintain significant rights in respect of tenurial disputes between the tenants and the lordship.[4] This and its corporate identity gave the lordship significance even after 1542.[9]

In 1563, Elizabeth I granted the lordship to her favourite Lord Robert Dudley, who later became the Earl of Leicester.[9] The grant claimed that Denbigh was given to him,

in as large and ample a manner...as was used when it was a lordship marcher with as large wardes as council [sic] learned could devise.[9]

Although the Laws in Wales Acts had not been modified – and the claim to have the same rights as a Marcher Lordship could not therefore be legally possible – Leicester had such political power that he could make this a reality in practice.[9] Leicester's administration of the lordship aroused violent hostility from the residents. After putting down a "rebellion" of the townspeople of Denbigh, Leicester sought to reconcile them by building the first Town Hall together with a Market Hall, and began the construction of a chapel.[10]

In 1585, Leicester mortgaged the lordship to a group of London merchants for £15,000.[11] On his death, with the debt unpaid, the Queen redeemed the mortgage and the Lordship returned to the crown in 1592/3.[11]

In 1696,[12] William III briefly made a grant of the lordship of Denbigh, to the Earl of Portland.[6] The inhabitants of Denbigh objected to this so strongly that they petitioned Parliament and had the grant rescinded.[6]

Over time, the crown sold off much of the original territory of the lordship, particularly during the reign of Charles I and, also during the Commonwealth period.[13]

Modern vestiges of the lordship

The lordship of Denbigh remains in existence, with the monarch as its Lord of the Manor.[14] As is the case with all crown land, the remaining lands of the lordship are vested in and managed by the Crown Estate. The Crown Estate in Denbighshire now comprises exclusively common land, together with the coastline,[15] and includes areas of the lordship such as parts of the Denbigh Moors (known in Welsh as Mynydd Hiraethog).[16]

Additionally, there is a Lordship of Denbigh "Estray Court".[14] According to a 2011 report on the Crown Estate in Wales published by the National Assembly for Wales:

In Denbigh The Crown Estate supports an annual Estray Court. Once a year, usually a Saturday in July, an Estray Court convenes allowing commoners the opportunity to claim their lost sheep. Successful claims entail the payment of a nominal "fine", imposed by the Court, which then sanctions the return of the sheep. Animals which are not claimed, or in respect of which claims are rejected, are auctioned by way of conclusion to the proceedings.[15]

When the last of the manorial courts were proposed to be abolished in 1977, the Estray Court was one of a handful that were maintained.[17] In proposing the legislation to abolish these local courts, Lord Elwyn-Jones, the then Lord Chancellor, told Parliament that "the Estray Court for the Lordship of Denbigh ... is a very useful court, and it would be quite wrong to abolish it".[14]

Lords of Denbigh

- Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln, 1284–1311

- Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 1311–1322, in right of his wife Alice de Lacy

- Hugh le Despenser, 1st Earl of Winchester, 1322–1326

- Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, 1327–1330

- William Montagu, 1st Earl of Salisbury, 1331–1344

- William Montagu, 2nd Earl of Salisbury, 1344–1354

- Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March, 1354–1360

- Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March, 1360–1381

- Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, 1381–1398

- Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, 1398–1425

- Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, 1425–1460

- Edward of York, 4th Duke of York, later Edward IV 1460–1461

- merged with the crown following Edward IV's accession 1461–1563

- Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, 1563–1588

- reverted to the crown, 1588/1592-1696

- William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland, 1696

- reverted to the crown, from 1696

References

- ↑ Michael Prestwich (1992). Edward I. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-7083-1076-2. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- 1 2 Thomas Jones Pierce (1959). "LACY (DE), of Halton". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ↑ Michael Prestwich (1992). Edward I. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-7083-1076-2. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 Adams, Simon (2002). Leicester and the Court: Essays on Elizabethan Politics. p. 294. ISBN 978-0719053252. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 Diane M. Korngiebel (2003). "Forty acres and a mule: the mechanics of English settlement in North-east Wales after the edwardian conquest". Haskins Society Journal. 14: 99–100. ISBN 9781843831167. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lewis, Samuel (1849). 'Denbigh – Denbighshire', A Topographical Dictionary of Wales. pp. 288–304. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bothwell, J. S. (2001). The Age of Edward III. pp. 49–50. ISBN 9781903153062. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Chris Given-Wilson (1987). The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages: The Fourteenth-Century Political Community. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-0710204912. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Adams, Simon (2002). Leicester and the Court: Essays on Elizabethan Politics. p. 295. ISBN 978-0719053252. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ "The History of Denbigh". Information Britain. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- 1 2 Adams, Simon (2002). Leicester and the Court: Essays on Elizabethan Politics. p. 296. ISBN 978-0719053252. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Williams, John (1836). Ancient & modern Denbigh: a descriptive history of the castle, borough . p. 257. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Sir Owen Morgan Edwards (1896). "The Lordship of Denbigh in 1649–50". Wales: A National Magazine for the English Speaking Parts of Wales. 3: 34. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Statement by the Lord Chancellor in Parliament". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 2 May 1977. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- 1 2 "The Crown Estate in Wales, pp.15–16" (PDF). National Assembly of Wales. 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "An Environmental Strategy and Action Plan for the Hiraethog Area, p.7" (PDF). Conwy County Borough Council. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "section 23(1)(a)(i), Administration of Justice Act, 1977". National Archives. Retrieved 9 July 2012.