The Lordship of Batiscan[1] was located on, and included 1/2 lieue of frontage along, the north shore of the St. Lawrence River (between the mouth of the Batisan and Champlain Rivers, in the current administrative area the Mauricie) in the province of Quebec, Canada. It was 20 lieues deep. Granted in 1639 to the Jesuits, colonization of the manor began in 1666, after an initial allotments were added to the census in 1665.) The northern boundary of the Lordship was past the source of the Saint-Maurice River. It was the deepest in the seigneurial system of New France. The Lordship of Batiscan became the most populous governed area of the Three Rivers by the end of the 17th Century.

In the 17th century, intensive colonization of the Lordship focused on the lowlands south of the Saint-Narcisse moraine, especially between 1665 and 1674, when the Jesuits approve 79 concessions. In the 18th century, the colonization effort involved two major phases: from 1705 to 1724 and from 1740 to 1760. Colonization north into pioneer zones north of the Saint-Narcisse moraine because lots below the moraine were fully settled. Today this area is included in Saint-Stanislas, Mauricie, Quebec whose civil registers opened in 1787. In the middle of the 18th century (the end of French rule), the Lordship of Batiscan ceased to exist and its population was included in the manors north of Lake Saint-Pierre or those of Lordship Yamachiche and Lordship of Rivière-du-Loup.

History

Concession to Jacques de la Ferté in 1636

On 15 January 1636, the Company of New France granted to Mr. Jacques de la Ferté, Abbot of St. Mary Magdalene of Châteaudun, himself a member of the company, a "fief and lordship of ten lieues in width (approximately 32.48 kilometres (20.18 mi)) along the shore of the St. Lawrence River, by twenty "lieues" (about 64.96 kilometres (40.36 mi)) north from the River. The territory included nearly all the land between the River Trois-Rivières and Batiscan River. The depth of this concession was unclear. The act of 1639 conceded to the Jesuits a part of this large territory to establish the Lordship of Batiscan.

Grant to the Jesuits in 1639

The territory of the Lordship of Batiscan was granted to Jesuits by a deed dated 13 March 1639 by their protector in France, Sir Jacques de la Ferté priest, counsellor, almoner Meeting of Roy, Abbot of St. Magdalene of Châteaudun, cantor and canon of the Sainte Chapelle du Palais Royal in Paris".[2]

This concession contract signed before Hervé Bergeron and Hyerosme Cousin, notaries of Chatelet in Paris, stated "an area of land that is from the Batiscan River to the Champlain River, quarter of a lieue[3] in confined or fourth "lieues" in the beyond ... to enjoy full stronghold faith and homage, high, middle and low justice ... and when the said piece of land will be cultivated will be required to give the Fathers said Mr. Abbot and his heirs a silver cross value of sixty soil tournaments and twenty years for recognition without Fathers can qu'iceux Estre received his faith and homage to the said fief if deus the said Lord, since he can not do that there is nobody in this country to meet for the said Sieur de la Madeleine ... "

Already established in Trois-Rivières since 1634, the Jesuits were familiar with the territory of Lower Batiscanie (especially along the river), including the site of Champlain where they met the Amerindians who had settled there. Obtaining the grant of such a lordship, the Jesuits' goal was to convert the [[Aboriginal peoples in Canada]|First Nations people]].

Busy with their apostolic mission at Trois-Rivières, fearing Iroquois attacks, and lacking resources, the Jesuits delayed the operation of the Lordship of Batiscan. In 1651, they opened up the Lordship of Cap-de-la-Madeleine which was populated quickly, being close to Trois-Rivières. The Jesuits claimed to be entitled to exploit the north bank of the river between the Rivers of Trois-Rivières and Batiscan. However, their right to the territory of the future Lordship of Champlain was returned to the king by decree in 1663, having not yet been exploited.

Given the handover in 1663 of part of their land rights, concessions, and many small fiefdoms on the north bank of the river, the Jesuits found themselves at risk of losing their right to use the Lordship of Batiscan. Under these circumstances, the Jesuits mandated Bishop Francois Malherbe to officially take possession of the manor of Batiscan, by signing a deed with the notary Laurent Portal, a tax attorney for the Jesuits, to Cap-de-la-Madeleine, and marking the territory.

Said deed is a reminder of the concession contract of 13 March 1639 granted the Jesuits and further defines the territory of the manor. The author of the act says "have carried on said place with Mr. Saule (sic) Boivin which, in our presence, surveyed the said lands and around ycelles cut large trees and bounded by other trees large cross made along iceux with axes ... And towards Brother Malherbe, made several good acts of possession, pulling weeds and throwing stones, and finally a true possessor accustomed to. And that and everything above it required that we act we granted him to serve him and argue and reason ... Guillaume de La Rue and Adrien Guillot, two citizens of Cape Town, were witnesses to the act.[4]

In Lower Canada, the seigneurial system was abolished on 18 December 1854.

Lordship of Champlain

The Lordship of Champlain, related to the west to the Lordship of Batiscan, was granted on 8 August 1664 and the new lord was Pézard La Touche. He immediately erected a stately mansion located on the tip of the mouth of the Champlain River. He also built a small chapel to serve several settler families already established in the area. The Lord of the designated "Latouche Champlain" land, Estienne Pezard, was assigned the rights in 1664 on two areas and 34 blocks of land grants in 1664 and 1665.[5]

Earthquake of 1663

According to reports of the earthquake of 5 February 1663, Native American and some French were living in the Lordship of Batiscan. This earthquake could significantly alter the relief in the Batiscanie, Quebec including the disappearance of waterfalls on the Batiscan River, the emergence of new rocks, the flattening of some mountains, and major cracks in the ground.[6]

The archives of the Lordship of Batiscan 1677–1823 are preserved in the archives of Montreal Central Library and Archives Fund of the Lordship of Batiscan 1677–1823 (P220) – Library and Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ)[7]

Concessions of lands to the habitants

Valley of Saint-Laurent

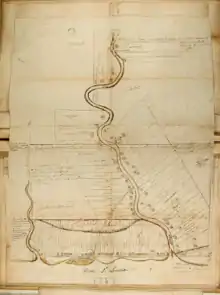

In 1665, the Jesuits distributed the first plots of land in Batiscan in a row along the St. Lawrence River, between the Champlain and Batiscan Rivers. From March 1666 to May 1667, seventy concessions were allocated to pioneers in a row along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River. At the end of the 17th century, land concessions were granted to pioneers along the eastern side of the Batiscan River. Sometimes the land was assigned or occupied informally occupied by pioneers without a notarial contract, a situation that was normalized a few years later with an official contract. Several concessions were awarded to ex-soldiers who were exempt from the usual obligations owed to Jesuit lords.[8]

Then lots were granted on the banks of the Champlain River, the Rivière à la Lime and finally in the upper valley of the Rivière à Veillet (Veillet River). With the expansion of colonization, the authorities opened other rows for the colonization, moving away from rivers. In the Lordship of Batiscan, three areas suitable for agriculture were: the valley near the river, the upper valley of the Rivière à Veillet and northern moraine.

A hamlet was formed around the mouth of the Rivière à Veillet which became the 19th century village of Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan. In 1723, the steward Michel Bégon de la Picardière signed an order authorizing the construction of a church in Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan on a piece of land belonging to Jean Veillet, a unique ancestor of all Veillet/te of America.[9]

Saint-Narcisse Morraine[10] (east-west)

Settlement to the north occurred on the Laurentian Mountains, which is a line of mountains stretching from east to west, parallel to the St. Lawrence River, usually between 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) and 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from the shore and the Saint-Narcisse great moraine. This moraine covers the current parishes of Saint-Narcisse, Saint-Prosper-de-Champlain and continues eastward into the Portneuf RCM. The area of the moraine is generally unsuitable for agriculture, but trees, including the maple, were able to be logged. The Batiscan River winds through the moraine and waterfalls impede navigation and require long portages. To the east of the Batiscan River, colonization was prevented by the Lac à la Tortue bog,[11] a large area of swamps and bogs located in the Mauricie region, with a total of area of 66 square kilometres.

Sector Rivière des Envies (Cravings River)

Forced to move north due to lack of available lots, new pioneers left the St. Lawrence Valley, the valley of the Rivière à la Lime and the upper valley of the Rivière à Veillet. They crossed the moraine by portaging to settle in the new area known as Rivière des Envies. The lots were granted successively to the north from the moraine by the Lords. In 1743, ten concessions were granted by the Lords to the Rivière des Envies.

In 1781, the Jesuits erected a large mill near the mouth of the Rivière des Envies in Saint-Stanislas. At this point, the Rivière des Envies included waterfalls more gentle than those on the Batiscan River. In 1786, a chapel was built in Saint-Stanislas.

From the beginning of British rule, colonization extended gradually up the Rivière des Envies. In 1833 an early settler stood near Lake Kapibouska. A Catholic mission, Saint-Just-de-Kapibouska, was established in 1851, and became the nucleus of the future parish of Saint-Tite.

Going up the Batiscan River, colonization stopped at the edge of the Lordship of Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade or the Manitou Falls (located at the boundary between Saint-Adelphe and Saint-Stanislas). The seigneurial system ended in 1854. In the 1980s, colonization continued to the north along the Batiscan River after the registry of rows in the current area of the municipality of Saint-Adelphe, including St-Thomas, which is now in Sainte-Thècle.

Summary of colonization

From 1666 to 1759, 246 acts of concessions have been listed in the Lordship of Batiscan. In 1760, the settlement reached 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of the St. Lawrence River. The main periods of awarding concessions by the Lordship of Batiscan were:

| Periods | Number of concession | Percentage of concessions (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1665–1674 | 79 | 32.11% |

| 1675–1704 | 10 | 4.06% |

| 1705–1724 | 66 | 26.82% |

| 1725–1739 | 14 | 5.69% |

| 1740–1759 | 77 | 31.30% |

See also

- Batiscan

- Batiscan River

- Batiscanie

- Government of Trois-Rivières

- Jesuit missions in North America

- Les Chenaux Regional County Municipality

- Lordship of Champlain

- Lordship of Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade

- Pierre-Paul River

- Rivière des Chutes

- Rivière des Envies

- Saint-Narcisse

- Saint-Séverin

- Saint-Stanislas

- Saint-Tite

- Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan

- Seigneurial system of New France

- Veillet River

Notes and references

- ↑ Jarnoux, Phllipe (1986). "The Colonization of the Seigneurie de Batiscan in the 17th 18th Centuries: Space and Men" (PDF) (in English and French). Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ↑ Raymond Douville,La seigneurie de Batiscan : chronique des premières années (1636–1681) (The Lordship of Batiscan: Chronicle of the Early Years (1636–1681)), Éditions du Bien public, Trois-Rivières, p. 8.(in French)

- ↑ A "lieue" is a unit of length formerly used in Europe and America. A "lieue" was a unit of length equal to the distance that a man can go on foot in an hour. For example, the former lieue in Paris (before 1674) is 10,000 feet or 3.248 kilometres.

- ↑ Raymond Douville, La seigneurie de Batiscan : chronique des premières années (1636–1681) (The Lordship of Batiscan: Chronicle of the Early Years (1636–1681)), Éditions du Bien public, Trois-Rivières, p. 15.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Chartier, La grande distribution des terres de 1665 (The Mass Distribution of Land in 1665), Collection Société historique de Champlain inc., Les Éditions Histoire Québec, collaboration of MRC Les Chenaux. This book, which deals with the retail land in 1664 and 1665 paints a portrait of the life of each of the new settlers and the stronghold of the manor, situated and each of their lands.

- ↑ Raymond Douville, La seigneurie de Batiscan : chronique des premières années (1636–1681) (The Lordship of Batiscan: Chronicle of the Early Years (1636–1681)), Éditions du Bien public, Trois-Rivières, p. 11 à 13, chapter "Le tremblement de terre de 1663" (The earthquake in 1663).

- ↑ Fonds seigneurie de Batiscan – 1677–1823 (P220) – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ).

- ↑ Jacques F. Veillette, book Histoire et généalogie des familles Veillet/te d'Amérique(History and genealogy of families Veillet/te of America), 1988, published by the Association of Families Veillet/te, 771 pages, p. 71.

- ↑ Jacques F. Veillette, book Histoire et généalogie des familles Veillet/te d'Amérique (History and genealogy of families Veillet/te of America), 1988, published by the Association of Families Veillet/te, 771 pages, p. 90.

- ↑ Serge Occhietti (2010-02-03). "The Saint-Narcisse morainic complex and early Younger Dryas events on the southeastern margin of the Laurentide Ice Sheet". Erudit (in English and French). Géographie physique et Quaternaire. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ↑ "The Lac-à-la-Tortue Bog". Nature Conservancy of Canada. Retrieved 2023-10-28.