This is a list of Mississippian sites. The Mississippian culture was a mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, inland-Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1500 CE, varying regionally.[1] Its core area, along the Mississippi River and its major tributaries, stretched from sites such as Cahokia in modern Illinois, the largest of all the Mississippian sites, to Mound Bottom in Tennessee, to the Winterville site in the state of Mississippi. The typical form were earthwork platform mounds, with flat tops, often the sites for temples or elite residences. Other mounds were built in conical or ridge-top forms. The culture reached peoples in settlements across the continent: Temple mound complexes were constructed also in areas ranging from Aztalan in Wisconsin to Crystal River in Florida, and from Fort Ancient, now in Ohio, to Spiro in Oklahoma. Mississippian cultural influences extended as far north and west as modern North Dakota.[2]

| Site | Image | State | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adams site | Kentucky | Located near Hickman in Fulton County, Kentucky, it consists of a 7.25-hectare (17.9-acre) village area built over the remains of a Late Woodland village with a central group of platform mounds around a central plaza and another smaller plaza area to the southwest of the largest mound, occupied during the Medley(1100 to 1300 CE) and Jackson(1300 to 1500 CE) Phases of the local chronology.[3] | |

| Adamson Mounds Site | South Carolina | Located near Camden, Kershaw County, South Carolina. It is a prehistoric Native American village site containing one large platform mound, a smaller mound, possibly a third still smaller mound, and a burial area. Lamar, Irene, or Pee Dee and dates between 1400 and 1700 CE.[4] | |

| Angel Mounds |  |

Indiana | A chiefdom in southern Indiana near Evansville. The large complex along the Ohio River had thirteen mounds and a population estimated at 1,000. It was the center of associated settlements. |

| Annis Mound and Village Site |  |

Kentucky | A Middle Mississippian single mound and village site located on the bank of the Green River in Butler County, Kentucky, several miles northeast of present-day Morgantown in the Big Bend region.[5] |

| Ashworth Archaeological Site |  |

Indiana | An archaeological site of the Caborn-Welborn variant of the Mississippian culture. |

| Avery site | Georgia | A multi-mound and village site, now destroyed, located in Troup County, Georgia east of the Chattahoochee River.[6] | |

| Aztalan State Park |  |

Wisconsin | A small Mississippian chiefdom in Wisconsin, the northern edge of the greater Mississippian culture. The village had one mound. |

| Battle Mound Site | Arkansas | Located in Lafayette County, Arkansas in the Great Bend region of the Red River basin, it has the largest mound of the Caddoan Mississippian culture | |

| Beasley Mounds Site | Tennessee | Also known as the Dixon Springs Mound Site, located at the confluence of Dixon Creek and the Cumberland River, near the unincorporated community of Dixon Springs in Smith County, Tennessee. More examples of Mississippian stone statuary have been found at this site than any other in the Middle Tennessee area.[7] | |

| Beaverdam Creek Archaeological Site | Georgia | A single mound and village site, now inundated by the Richard B. Russell Reservoir in Elbert County, Georgia, located approximately 0.8 km from the creek's confluence with the Savannah River. Abandoned sometime after 1300 CE.[8] | |

| Belcher Mound Site | Louisiana | A Caddoan Mississippian site located in Caddo Parish, Louisiana[9] in the Red River Valley 20 miles north of Shreveport[10] and about one-half mile east of the town of Belcher, Louisiana.[11] | |

| Bell Field Mound Site | Georgia | A South Appalachian Mississippian single mound site located on the western bank of the Coosawattee River below the Coosawatee's junction with Talking Rock Creek. The site, along with the Sixtoe Mound and Little Egypt sites, were destroyed by the construction of Carters Dam in the 1970s.[12] | |

| Bottle Creek Indian Mounds |  |

Alabama | An island in the Mobile–Tensaw River Delta in Baldwin County, Alabama, containing 18 platform mounds, constructed by the Pensacola culture between 1250 and 1550 CE.[13] |

| Boyd Mounds Site |  |

Mississippi | A site from the Late Woodland and later Mississippian culture located in Madison County, Mississippi near Ridgeland. It is located at mile 106.9 on the old Natchez Trace, now the Natchez Trace Parkway.[14] |

| Brentwood Library Site | Tennessee | Also known as the Jarman Farm Site, it is a village and associated burial area located in Brentwood, Tennessee. It was occupied during the Thurston Phase of the local chronology, and artifacts from the site have been radiocarbon dated to 1298 to 1465 CE.[15] | |

| Brick Church Mound and Village Site | Tennessee | A multi-mound palisaded village site located in Nashville in Davidson County, Tennessee[16] | |

| Bussell Island | Tennessee | An island at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River in Loudon County, Tennessee, believed to have been the location "Coste," visited by Hernando de Soto and his expedition in 1540. Designated as 40LD17. Mounds and burials were found here. | |

| Caddoan Mounds State Historic Site | Texas | Also known as the George C. Davis Site (41CE19), a Caddoan Mississippian site located in Cherokee County, Texas 26 miles west of Nacogdoches, Texas on Texas State Highway 21, near its intersection with U.S. Route 69 in the Piney Woods region of east Texas | |

| Cahokia |  |

Illinois | Near East St. Louis, Illinois, Cahokia was the largest and most influential of the Mississippian culture centers and the largest Pre-Columbian settlement north of Mexico. Discoveries found at the massive site, which still has numerous mounds, include the largest Pre-Columbian earthwork in the Americas (Monks Mound), evidence of copper working (Mound 34), astronomy (Cahokia Woodhenge), and ritual retainer burials (Mound 72). |

| Campbell Archeological Site |  |

Missouri | The Campbell Archeological Site ( 23 PM 5), is a site in Southeastern Missouri occupied by the Late Mississippian Period Nodena phase from 1350 to 1541 CE. |

| Carcajou Point site | Wisconsin | The Carcajou Point site (47JE2, aka the Carcajou site, Carcajou village or White Crow's village) is located in Jefferson County, Wisconsin, on Lake Koshkonong. It is a multi-component site with prehistoric Upper Mississippian Oneota and Historic components. | |

| Castalian Springs Mound Site |  |

Tennessee | In Castalian Springs, Tennessee, the site was once home to a substantial Mississippian-period (1000-1400 CE) village with 12 known mounds at the site. |

| Chauga Mound | South Carolina | A South Appalachian Mississippian single mound and village site located on the northern bank of the Tugaloo River, 1,200 feet (370 m) north of the mouth of the Chauga River in Oconee County, South Carolina, now inundated by Lake Hartwell.[17] Historic Cherokee were the last occupants of the village, dated to the early eighteenth century.[17] | |

| Chucalissa Indian Village |  |

Tennessee | The site is a Walls phase Mississippian site dating to the 15th century, now located within the city of Memphis in West Tennessee. It was occupied, abandoned, and reoccupied several times throughout its history, spanning from 1000 to 1550 CE. |

| Citico (Hamilton County, Tennessee) | Tennessee | In the Coosa confederacy, the site of a large Mississippian mound dating back to the 15th century, located in the city of Chattanooga on Citico Creek. The town was occupied, abandoned and reoccupied several times throughout its history, spanning from 1000 (Muscogee) to 1778 CE (Cherokee). | |

| Cloverdale archaeological site | Missouri | An important archaeological site near St. Joseph, Missouri. It is located at the mouth of a small valley that opens into the Missouri River. It was occupied by Kansas City Hopewell (ca. 100 to 500 CE) peoples and later by Mississippian-influenced Steed-Kisker peoples (ca. 1200 CE). Because of the many Cahokia-style projectile points found at the site, it is believed to have been a trade partner or outpost of the much larger Cahokia polity.[18] | |

| Crystal River Archaeological State Park | Florida | [2] | |

| Denmark Mound Group | Tennessee | Mound and village site on a low bluff overlooking Big Black Creek, a tributary of the Hatchie River near Denmark in Madison County, Tennessee. Features include a village with over 70 structures, 2 rectangular platform mounds, and a small conical burial mound, as well as possible evidence of a surrounding palisade.[19] | |

| Dickson Mounds |  |

Illinois | A settlement site and burial mound complex near Lewistown, Illinois in Fulton County on a low bluff overlooking the Illinois River. The site is named in honor of chiropractor Don Dickson, who began excavating it in 1927 and opened a private museum that formerly operated on the site.[20] |

| Dyar site | Georgia | A single mound and village site located in Greene County, Georgia, inhabited almost continuously from 1100 to 1600 CE and now submerged under Lake Oconee.[21] | |

| Eaker site |  |

Mississippi | The site is the largest and most intact Late Mississippian Nodena phase village site within the Central Mississippi Valley.[22] |

| Emerald Mound and Village Site |  |

Illinois | A Middle Mississippian period archaeological site located near Lebanon, Illinois. The platform mound is the second-largest Pre-Columbian earthwork in Illinois, after Monk's Mound at Cahokia. |

| Emerald Mound site |  |

Mississippi | A Plaquemine Mississippian-period archaeological site located on the Natchez Trace Parkway near Stanton, Mississippi. The site dates from the period between 1200 and 1730 CE. The platform mound is the second-largest Pre-Columbian earthwork in the country, after Monk's Mound at Cahokia |

| Emmons Cemetery Site | Illinois | A Middle Mississippian culture site located in Kerton Township, Fulton County, Illinois, on the edge of a bluff overlooking the Illinois River to its east. The location was a used as a cemetery and several unique and rare items were found interred with the burials.[23] The burials were in several small burial mounds located on the lower slope. The cemetery area measures about 50 feet (15 m) square.[24] | |

| Etowah Indian Mounds |  |

Georgia | One of the major Mississippian chiefdoms, belonging to the South Appalachian Mississippian culture, located in northwestern Georgia, believed by some to be a long-standing antagonist of the Moundville polity. |

| Fewkes Group Archaeological Site |  |

Tennessee | Located in the city of Brentwood, in Williamson County, Tennessee. The 15-acre site consists of the remains of a Late Mississippian-culture mound complex and village roughly dating to 1050-1475 CE.[25] The site is on the western bank of the Little Harpeth River; it has five mounds, some used for burials; others, including the largest, were ceremonial platform mounds.[26] |

| Fort Walton Mound |  |

Florida | The Fort Walton Mound was built about 1300 CE by Fort Walton Culture. Located in Fort Walton Beach, Florida, in the Florida Panhandle. The intersection of State Road 85 and U.S. Route 98 is near the site. |

| Garden Creek site | North Carolina | Two Pisgah phase villages, occupied from 600 to 1200 CE, and three mounds (31Hw1-3) in Haywood County, North Carolina | |

| Grand Village of the Natchez |  |

Mississippi | The main village of the Natchez people, with three mounds. A Plaquemine Mississippian-period archaeological site used and maintained into historic times |

| Holly Bluff site |  |

Mississippi | Type site for the Lake George phase of the Plaquemine culture, on the southern margin of the Mississippian cultural advance down the Mississippi River, and on the northern edge of the Cole's Creek and Plaquemine cultures of the South. |

| Hoojah Branch Site | Georgia | A South Appalachian Mississippian single mound and village site located in Rabun County, Georgia, about one mile east of Dillard, Georgia in the Chattahoochee National Forest. | |

| Hovey Lake-Klein Archeological Site |  |

Indiana | A Caborn-Welborn site, located on the west bank of Hovey Lake, a backwater lake near the Ohio River close to its confluence with the Wabash River. The site was an extensive village, with occupation dating between 1400 and 1650 CE. |

| Jaketown Site |  |

Mississippi | A site with two mounds in Humphreys County, Mississippi, dating from roughly 1100 CE to 1500 CE, located along Mississippi Highway 7 approximately seven miles north of Belzoni. The largest platform mound at the site, Mound B, is 23 feet (7.0 m) in height with a base of 150 feet (46 m) by 200 feet (61 m). It has a projection on its eastern side that is thought to have been a ramp once used as a stairway. To its northeast is Mound C, another platform mound with a height of 15 feet (4.6 m).[27] |

| Jere Shine site | Alabama | A South Appalachian Mississippian culture multi-mound and village site located near the confluence of the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers in modern Montgomery County, Alabama, and likely occupied from 1400 to 1550 CE. In addition to its Mississippian-era Shine I-phase, it is the largest settlement associated with the Shine II-phase of the lower Tallapoosa River.[28] | |

| Joara |  |

North Carolina | The largest chiefdom in North Carolina at contact by Spanish Juan Pardo in 1566; also possibly the furthest northeastern Mississippian chiefdom center, near Morganton |

| Joe Bell site |  |

Georgia | A village site occupied during the local Duvall Phase and Bell Phases of the South Appalachian Mississippian period and located south of the mouth of the Apalachee River on the western bank of the Oconee River; it is now submerged under Lake Oconee.[29] |

| Jordan Mounds |  |

Louisiana | A multi-mound site (16 MO 1) in Morehouse Parish, Louisiana near Oak Ridge, Louisiana.[30] The site was constructed during the proto-historic period between 1540 and 1685.[31] |

| Kincaid Mounds State Historic Site |  |

Illinois | A major Mississippian mound center in southern Illinois, across the Ohio River from Paducah, Kentucky |

| King Archaeological Site |  |

Georgia | A 5 acres (0.020 km2) proto-historic Barnett Phase village located on the western bank of the Coosa River in Floyd County, Georgia. The site was a satellite village associated with the Nixon polity, remnants of the Coosa chiefdom encountered by de Soto in 1540. It was occupied during the mid to late 1500s.[32] |

| Lamar Mounds and Village Site | Georgia | Type site for the Lamar phase, this is located on the banks of the Ocmulgee River in a swamp in Bibb County, Georgia. It is a few miles to the southeast of Macon and the large Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, of which it is a unit. The national monument and historic district was created in 1936 and is run by the National Park Service.[33] Historians and archaeologists have theorized that the Lamar site may be the location of the main village of the Ichisi, recorded by the Hernando de Soto expedition in 1539.[34] | |

| Letchworth Mounds |  |

Florida | A Fort Walton Culture Florida State Park located approximately six miles west of Monticello, a half mile south of U.S. 90, in northwestern Florida. It contains the state's tallest ceremonial mound (46 feet), estimated to have been built 1100 to 1800 years ago. |

| Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park |  |

Florida | The site is one of the most important sites in Florida, a former chiefdom and ceremonial center of the Fort Walton Culture. The complex originally included six mounds, a constructed plaza, and numerous individual village residences. Located in the Florida Panhandle, it is in northern Tallahassee, on the south shore of Lake Jackson. |

| Liddell Archeological Site |  |

Alabama | Located in Wilcox County, Alabama, it covers 50 acres (20 ha) and shows evidence of human occupation from 9000 BCE to 1800 CE. It is best known for its Mississippian artifacts from the Burial Urn Culture period. The Liddell, Stroud, and Hall families donated the site to Auburn University after its discovery.[35] |

| Little Egypt site | Georgia | Located in Murray County, Georgia, near the junction of the Coosawattee River and Talking Rock Creek. It was destroyed in 1972 during construction of the dam of Carters Lake. It was situated in a flood plain between the Ridge and Valley, and Piedmont sections of the state.[36] | |

| Long Swamp Site | Georgia | Located in Cherokee County, Georgia on the north shore of the Etowah River. St Rt 372 passes by here. The site consists of a South Appalachian Mississippian village with a palisade and a platform mound.[37] | |

| Mandeville site | Georgia | A multi-mound and village site located in Clay County, Georgia and now submerged under Walter F. George Lake, which is a part of the Chattahoochee River basin. Occupied during the Middle Woodland period by Early Swift Creek culture, and later by peoples of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture.[38] | |

| Mangum Mound Site | Mississippi | A Plaquemine site in Claiborne County, Mississippi, located at milepost 45.7 on the Natchez Trace Parkway. An avian-themed, repoussé Mississippian copper plate was discovered there in 1936.[39] | |

| Marshall Site | Kentucky | An Early Mississippian site located near Bardwell in Carlisle County, Kentucky, on a bluff spur overlooking the Mississippi River floodplain. It was occupied from about 900 to about 1300 CE during the James Bayou Phase of the local chronology; it was abandoned sometime during the succeeding Dorena Phase.[40] The large village site has evidence of once having had a platform mound and other earthworks.[41] | |

| Menard–Hodges site | Arkansas | In Arkansas, it includes two large mounds as well as several house mounds, possibly the Province of Anilco encountered in 1540 by the Hernando de Soto Entrada.[42] | |

| Mitchell Archaeological Site | South Dakota | A site in Davison County, South Dakota, near Mitchell, South Dakota. Mitchell Site is the only reliably dated site (c. 1000 CE) pertaining to the Lower James River Phase (Initial Variant) of the migration of late Mississippian culture to the Middle Missouri Valley. It is distinctive for its evidence relating mortuary practices to other intra-site practices. | |

| Mound Bottom |  |

Tennessee | The complex in Cheatham County, Tennessee consists of ceremonial and burial mounds, a central plaza, and habitation areas, built between 950 and 1300 CE. |

| Moundville Archaeological Site |  |

Alabama | Ranked with Cahokia as one of the two most important sites at the core of the classic Mississippian culture,[43] it is located near Tuscaloosa, Alabama. |

| Murphy Mound Archeological Site |  |

Missouri | The Murphy Mound Archeological Site ( 23-PM-43 ), is an archaeological site in Southeastern Missouri occupied from 1350 to 1541 CE. |

| Nacoochee Mound |  |

Georgia | An earthen mound on the banks of the Chattahoochee River in White County, in the northeast part of the state of Georgia. The junction of Georgia Highways 17 and 75 is near here. |

| Nikwasi | North Carolina | A South Appalachian Mississippian single mound and village site that was also the site of a historic Cherokee town of the same name, located along the Little Tennessee River. Present-day Franklin, North Carolina developed here and has protected the mound.[44] | |

| Nodena site |  |

Arkansas | Type site for a Late Mississippian Nodena phase, which dates from about 1400-1700 CE; believed by many archaeologists to be the province of Pacaha, visited by Hernando de Soto in 1542.[42] |

| Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park |  |

Georgia | The center of a South Appalachian Mississippian chiefdom, this 702 acres (2.84 km2) site near Macon, Georgia, has multiple ceremonial mounds, a burial mound, and defensive trenches remaining. It was also used by descendants who formed the historic the Muskogee-speaking Creek (also known as Muscogee) peoples and continued use of this site. |

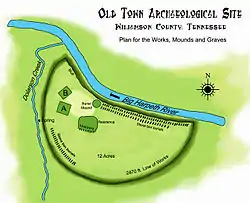

| Old Town Archaeological Site |  |

Tennessee | Village site along the Natchez Trace on the banks of the Harpeth River in Franklin, Tennessee. Occupancy dated from approximately 900 to 1450 CE. |

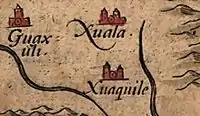

| Parkin Archeological State Park |  |

Arkansas | The type site for the Late Mississippian Parkin phase, believed by many archaeologists to be the province of Casqui visited by Hernando de Soto in 1542.[42] |

| Prather Site |  |

Indiana | Located on a loess-capped upland ridge 4.9 kilometres (3.0 mi) west of the Ohio River and 2.4 kilometres (1.5 mi) east of Silver Creek in the Falls of the Ohio region in Clark County, Indiana. It was the principal ceremonial center of the Prather Complex, the northeasternmost regional variant of the Middle Mississippian culture. It also bordered on several Upper Mississippian cultures, including the Fort Ancient peoples of Southern Indiana, Southern Ohio and Northeastern Kentucky.[45] |

| Punk Rock Shelter | Georgia | A rock shelter found in Putnam County, Georgia; it is now inundated by Lake Oconee. The only known site in the Oconee Valley that produced a large collection of vessels from the Lamar phase and Savannah Phase.[46] | |

| Rembert Mounds | Georgia | A South Appalachian Mississippian multi-mound and village site located in Elbert County, Georgia in the area that was submerged by Lake Strom Thurmond, created by damming of the Savannah River.[47] | |

| Riverview Mounds Archaeological Site | Tennessee | A Middle Mississippian multi-mound and village site located in Montgomery County, Tennessee, just south of Clarksville on the Cumberland River.[48] | |

| Rowlandton Mound Site |  |

Kentucky | Located in Paducah in McCracken County, Kentucky, on the edge of an old oxbow lake a little south of the Ohio River. Occupied from c. 1100 to c. 1350 CE, the 3-hectare (7.4-acre) site has a large platform mound and an associated village area.[49] |

| Sellars Indian Mound |  |

Tennessee | A single mound site located near Lebanon, Tennessee, occupied from about 1000 CE until 1300 CE |

| Shiloh Indian Mounds Site |  |

Tennessee | Shiloh Indian Mounds Site is an archaeological site of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture. Located beside the Tennessee River, it was inhabited from around 1000 CE until it was abandoned in approximately 1450 CE. After the Civil War, the Shiloh National Military Park was established around it.[50] Because it has been included within the national military park for so long, it has not been disturbed by modern farming. Remains of the original structures of wattle and daub are still visible as low rings or mounds. It is one of the few places in the eastern U.S. where such remains are visible.[51][52] |

| Sixtoe Mound | Georgia | A single mound and village site located in Murray County, Georgia; it was excavated by Arthur Randolph Kelly from 1962 to 1965 as a part of the Carters Dam salvage project conducted for the National Park Service by the University of Georgia. The site was inundated by a reservoir created by the dam.[53] | |

| Slack Farm | Kentucky | Slack Farm is a site of the Caborn-Welborn culture(a Late Mississippian variant) located near Uniontown, Kentucky, close to the confluence of the Wabash and Ohio rivers. The site included a single platform mound and an extensive village occupation, dating between 1400 and 1650 CE. | |

| Spiro Mounds |  |

Oklahoma | Located in eastern Oklahoma, this is a large complex with multiple mounds. It is one of the best-studied archaeological centers of Mississippian culture; a number of significant artifacts were recovered. But looters had previously attacked the mounds and stolen many artifacts. |

| Starr Village and Mound Group | Illinois | Located on a bluff overlooking Macoupin Creek southwest of Carlinville in Macoupin County, Illinois.[54] | |

| Sugarloaf Mound | Missouri | The sole remaining Mississippian platform mound in St. Louis, Missouri. The mound covers three city blocks, measures approximately 40 feet in height, 100 feet north–south and 75 feet east/west. | |

| Summerour Mound site | Georgia | A South Appalachian Mississippian single mound and village site located in Forsyth County, Georgia, formerly on a floodplain of the Chattahoochee River in northern Georgia but now submerged under Lake Lanier.[55] | |

| Swallow Bluff Island Mounds | Tennessee | The northernmost outpost of the Shiloh polity, located near Saltillo on an island in the Tennessee River in Hardin County, Tennessee. The site featured two platform mounds, a plaza, and a village area.[56] | |

| Talley Mounds | Alabama | A Woodland and Mississippian settlement site on the banks of Valley Creek near present-day Bessemer, Alabama; it is thought to have supported a population of up to 1,000 inhabitants. It was occupied as early as 5000 years ago. Three earthwork mounds were constructed around 1100 CE by people of the Mississippian culture. The site was described in the 19th century and excavated in the 1930s. It has since been redeveloped.[57] | |

| Taskigi Mound |  |

Alabama | Also known as the Mound at Fort Toulouse – Fort Jackson Park (1EE1), this is a South Appalachian Mississippian culture palisaded mound and village site on a 40 feet (12 m) bluff between the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers. It is located at their confluence forming the Alabama River, near the present-day town of Wetumpka in Elmore County, Alabama.[58] |

| Tolu Site | Kentucky | A three-mound site near the unincorporated community of Tolu, Crittenden County, Kentucky. It was built and occupied by people of the Mississippian culture between 1200 and 1450 CE.[59] Tolu Site is part of the Angel Phase of the Mississippian period. | |

| Towosahgy State Historic Site |  |

Missouri | A Mississippian chiefdom in southeastern Missouri |

| Town Creek Indian Mound |  |

North Carolina | A South Appalachian Mississippian chiefdom in North Carolina, generally attributed to the historic Pee Dee people |

| Travellers Rest (Nashville, Tennessee) |  |

Tennessee | In 1799, Judge John Overton (1766–1833) built this two-story structure with four rooms on his plantation. Overton originally named his property "Golgotha" because of the numerous prehistoric skulls that were unearthed while the cellar of the house was dug. Overton changed the name of his plantation to Travellers Rest in the early 19th century to reflect the restorative effect of returning to his home after the long rides on horseback that he had to undertake as a circuit judge.[60] In the late 20th century, archaeologists identified the human remains found at the Overton plantation as burials associated with a large Mississippian village site. In 1996 when a modern barn structure was built on the property, 13 stone box coffins were discovered. These have also been dated to the Mississippian culture. |

| Turk Site | Kentucky | This multi-mound site is located near Bardwell in Carlisle County, Kentucky, on a bluff spur overlooking the Mississippi River floodplain. The 2.5-hectare (6.2-acre) site was occupied during the Dorena Phase (1100 to 1300 CE) and into the Medley Phase (1300-1500 CE) of the local chronology.[61] Its inhabitants may have come from the Marshall Site, which is located on the nearest adjacent bluff spur. The layout of the site is characteristically Mississippian, with a number of platform mounds surrounding a plaza.[62][41] | |

| Twin Mounds Site | Kentucky | Also known as the Nolan Site, it is located near Barlow in Ballard County, Kentucky, just north of the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. The site consists of two large platform mounds built around a central plaza, and a large, 2 metres (6.6 ft) thick midden area.[63] | |

| Ware Mounds and Village Site |  |

Illinois | Also known as the Running Lake Site(11U31), this is a village site with four platform mounds located west of Ware in Union County, Illinois.[64] |

| Welborn Village Archeological Site | Indiana | Also known as the Murphy's Landing Site, this is an archaeological site of the Caborn-Welborn culture. | |

| Wickliffe Mounds |  |

Kentucky | A chiefdom on a bluff top in the far western Kentucky town of Wickliffe |

| Wilbanks Site | Georgia | A Late South Appalachian Mississippian single mound and village site in Cherokee County, Georgia. It was located about midway between the present-day towns of Cartersville, Georgia to the west, and Canton, Georgia to the east on the south bank of the Etowah River. It was flooded and submerged by the creation of Lake Allatoona after construction of a dam on the river.[65] | |

| Winterville site |  |

Mississippi | The type site for the Winterville phase of the Plaquemine Mississippian culture. |

See also

References

- ↑ "Mississippian Period: Overview". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- 1 2 Waldman, Carl (2009). Atlas of the North American Indian. Facts on File. pp. 32. ISBN 978-0-8160-6858-6.

- ↑ Lewis, R. Barry (1996). "Chapter 5:Mississippian Farmers". Kentucky Archaeology. University Press of Kentucky. p. 142. ISBN 0-8131-1907-3.

- ↑ Robert L. Stephenson (March 1970). "Adamson Mounds Site" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ↑ Lewis, R. Barry (1996). "Chapter 5: Mississippian Farmers". Kentucky Archaeology. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 135–137. ISBN 0-8131-1907-3.

- ↑ Harold, Huscher (1972), The Avery Site : Archaeological Investigations in the West Point Dam Area: A Preliminary Report, vol. 1 of 2, Department of Sociology and Anthropology: University of Georgia

- ↑ Kevin E. Smith; James V. Miller (2009). Speaking with the Ancestors-Mississippian Stone Statuary of the Tennessee-Cumberland region. University of Alabama Press. pp. 53–67. ISBN 978-0-8173-5465-7.

- ↑ Anderson, David G. (1996). "Chiefly Cycling and Large-Scale Abandonments as Viewed from the Savannah River Basin". In John F. Scarry (ed.). Political Structure and Change in the Prehistoric Southeastern United States. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 150–191.

- ↑ "Locality information for Faunmap locality Belcher Mound, LA". Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ↑ "The Caddo Indians of Louisiana". Archived from the original on 2009-11-09. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ↑ "Historical-Belcher". Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ↑ Kelly, Arthur R, Explorations at Bell Field Mound and Village Seasons 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, University of Georgia Archaeology Laboratory Manuscript

- ↑ "Bottle Creek Site". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ↑ "Indian Mounds of Mississippi : Boyd Mounds Site". NPS.GOV.

- ↑ Lankford, George E.; Reilly, F. Kent; Garber, James F. (2011-01-15). Visualizing the Sacred: Cosmic Visions, Regionalism, and the Art of the Mississippian World. University of Texas Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-292-72308-5.

- ↑ Barker, Gary; Kuttruff, Carl (Summer 2010). Michael C. Moore (ed.). "A Summary of Exploratory and Salvage Archaeological Investigations at the Brick Church Pike Mound Site (40DV39), Davidson County, Tennessee" (PDF). Tennessee Archaeology (Editors Corner). Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology. 5 (1).

- 1 2 Hally, David J. (1998-08-01). "Chauga". In Gibbon, Guy; Kenneth M., Ames (eds.). Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-8153-0725-9.

- ↑ "Cloverdale Archaeological Site". Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ↑ Scott Hadley Jr. (2013). Multi-Staged Research at the Denmark Site, A Small Early-Middle Mississippian Town (Masters thesis). University of Memphis.

- ↑ "History". State of Illinois. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ↑ Smith, Marvin T. (1994). "Archaeological Investigations at the Dyar Site, 9GE5" (PDF). University of Georgia.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks Program-Eaker Site". Archived from the original on 2009-08-13. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ Parmalee, Paul W. (June 1967). "Additional noteworthy records of birds from archaeological sites" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 79 (2).

- ↑ Griffin, James B.; Morse, Dan F. (1961). "The Short Nosed God from the Emmons Site, Illinois". American Antiquity. Society for American Archaeology. 26 (4): 560. doi:10.2307/278753. JSTOR 278753. S2CID 163224869.

- ↑ Hutt, Sherry. "Notice of Inventory Completion: Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Division of Archaeology, Nashville, Tennessee". Federal Register. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ Warwick, Rick (2010). Historical Markers of Williamson County, Tennessee, Revised: A Pictorial Guide. Nashville, Tennessee: Panacea Press.

- ↑ "Jaketown Site". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M.; Carmen Chaves Tesser (1994). The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521-1704. Athens: University of Georgia Press. pp. 379–381. ISBN 978-0-8203-1473-0.

- ↑ Williams, John Mark. The Joe Bell Site: Seventeenth Century Lifeways on the Oconee River. Diss. U of Georgia, 1983

- ↑ Wes Helbling (2009-10-15). "A look at ancient Morehouse". Bastrop Daily Enterprise. Archived from the original on 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- ↑ Tristam R. Kidder (1992). "Excavations at the Jordan Site (16MO1) Morehouse Parish, Louisiana". Southeastern Archaeology. 11 (2): 109–131. JSTOR 40712974.

- ↑ Marvin T. Smith (2002-08-07). "Late Prehistoric/Early Historic Chiefdoms (ca. A.D. 1300-1850) : The Nature of Chiefdoms". New Georgia Encyclopedia. University of Georgia and Georgia Humanities Council.

- ↑ Williams, Mark (1999). "Lamar Revisited : 1996 Test Excavations at the Lamar Site" (PDF). Lamar Institute, University of Georgia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-12.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. pp. 157–162. ISBN 9780820318882.

- ↑ "Office of University Outreach Scholarship Grant Black Belt Environmental Science and Arts Program: 2005 Progress Report" (PDF). Auburn University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ Hally, David; Beverly Cooper; Janet Roth (1978), Archeological Investigation of the Little Egypt Site (9Mu102), Murray County, Georgia, 1969 Season, University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology Series

- ↑ "Long Swamp site reexamined". The Society for Georgia Archaeology. 2008-10-01. Archived from the original on 2014-09-03. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- ↑ John H. Blitz; Karl G. Lorenz (April 28, 2006). The Chattahoochee Chiefdoms. University Alabama Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8173-5277-6.

- ↑ Cotter, John L. (July 1952). "The Mangum Plate". American Antiquity. 18 (1): 65–68. doi:10.2307/276247. JSTOR 276247. S2CID 164178066.

- ↑ Lewis, R. Barry (1996). "Chapter 5:Mississippian Farmers". Kentucky Archaeology. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 128–130. ISBN 0-8131-1907-3.

- 1 2 Pollack, David (2008), "Chapter 6:Mississippi Period" (PDF), in David Pollack (ed.), The Archaeology of Kentucky: An update, Kentucky Heritage Council, pp. 614–615, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-17, retrieved 2010-10-29

- 1 2 3 Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820318882.

- ↑ "Southeastern Prehistory: Mississippian and Late Prehistoric Period". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ↑ Duncan, Barbara R.; Riggs, Brett H (2003). Cherokee Heritage Trails Guidebook. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 0-8078-5457-3.

- ↑ Munson, Cheryl Ann; McCullough, Robert G. "Topographic mapping and transect survey of the Prather Archaeological site (12-CL-4), Clark County, Indiana" (PDF). Indiana University-Bloomington.

- ↑ Williams, Mark. "Archaeological Investigations at the Punk Rock Shelter (9PM211)" (PDF). LAMAR Institute Publication 9. LAMAR Institute. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ↑ Caldwell, Joseph R. (1953), The Rembert Mounds, Elbert County, Georgia, Smithsonian Institution: Bureau of American Ethnology 154, pp. 303–20

- ↑ Deter-Wolf, Aaron. "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: RiverView Mounds Archaeological Site (40MT44), Montgomery County Tennessee". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ↑ Kriesa, Paul P. (1998). "Chronology in Western Kentucky". In O'Brien, Michael J.; Dunnell, Robert C. (eds.). Changing perspectives on the archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0909-8.

- ↑ Paul D. Welch (2005). Archaeology at Shiloh Indian Mounds, 1899-1999. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1481-1.

- ↑ "Shiloh Indian Mounds". Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ "Shiloh Indian Mounds - National Historic Landmark". Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ Williams, J. Mark. (1990). Lamar Archaeology: Mississippian Chiefdoms in the Deep South. University of Alabama Press.

- ↑ Conrad, Lawrence A. (2000-06-30). "The Middle Mississippian Cultures of the Central Illinois River Valley". In Emerson, Thomas E.; Lewis, R. Barry (eds.). Cahokia and the Hinterlands: Middle Mississippian Cultures of the Midwest. University of Illinois Press. pp. 90–100. ISBN 978-0-252-06878-2.

- ↑ Thomas J. Pluckhahn (Winter 1996). "Summerour Mound (9FO15) and Woodland Platform Mounds in the Southeastern United States". Southeastern Archaeology. 15 (2): 191–211. JSTOR 40713077.

- ↑ Welch, Paul D. (Summer 2004). Michael C. Moore (ed.). "Fieldwork at Swallow Bluff Island Mounds, Tennessee (40HR16) in 2003" (PDF). Tennessee Archaeology. Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology. 1 (1): 36–48.

- ↑ Cyrus Thomas (1894). 12th Annual Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1890-91. Government Printing Office. pp. 290–292.

- ↑ "Mound at Fort Toulouse – Fort Jackson Park". University of Alabama.

- ↑ Kevin E. Smith; James V. Miller (2009). Speaking with the Ancestors-Mississippian Stone Statuary of the Tennessee-Cumberland region. University of Alabama Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-8173-5465-7.

- ↑ "Travellers Rest – The 1799 Home of Judge John Overton". travellersrestplantation.org. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ Lewis, R. Barry (1996). "Chapter 2: The Western Kentucky border and the Cairo lowland". In McNutt, Charles H. (ed.). Prehistory of the Central Mississippi Valley. University of Alabama Press. pp. 67–70. ISBN 0-8173-0807-5.

- ↑ Lewis, R. Barry (1996). "Chapter 5:Mississippian Farmers". Kentucky Archaeology. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 128–130. ISBN 0-8131-1907-3.

- ↑ Pollack, David (2008), "Chapter 6:Mississippi Period" (PDF), in David Pollack (ed.), The Archaeology of Kentucky: An Update, Kentucky Heritage Council, p. 626, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-17, retrieved 2010-10-29

- ↑ Kevin E. Smith; James V. Miller (2009). Speaking with the Ancestors-Mississippian Stone Statuary of the Tennessee-Cumberland region. University of Alabama Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8173-5465-7.

- ↑ Sears, William H. (1958), The Wilbanks Site (9CK-5), Georgia. River Basin Survey Papers 12, Washington D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology, p. 138