| Lightning Brigade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | February 1863 – November 1863 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Union Army |

| Type | Mounted Infantry |

| Size | Five regiments and one battery:

|

| Nickname(s) | Lightning Brigade Hatchet Brigade |

| Equipment | Spencer repeating rifle |

| Engagements | American Civil War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. John T. Wilder |

.tiff.jpg.webp)

The Lightning Brigade, also known as Wilder's Brigade or the Hatchet Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade from the American Civil War in the Union Army of the Cumberland from March 8, 1863, through November 1863. A novel unit for the U.S. Army, its regiments were nominally the 1st Brigade[4] of Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds' 4th Division of Thomas' XIV Corps. Operationally, they were detached from the division and served as a mobile mounted infantry to support any of the army's corps. Colonel John T. Wilder was its commander. As initially organized, the brigade had the following regiments:[5]

- 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry:[6] Col. Smith D. Atkins (after 10 July 1863)

- 98th Illinois Mounted Infantry:[7] Col. John J. Funkhouser (w), Lt. Col. Edward Kitchell

- 123rd Illinois Mounted Infantry:[8] Col. James Monroe

- 17th Indiana Mounted Infantry:[9][10] Maj. William T. Jones

- 72nd Indiana Mounted Infantry:[11][12] Col. Abram O. Miller

- 18th Independent Battery Indiana Light Artillery:[13][14] Capt. Eli Lilly

Formation

Throughout 1862, Major General William S. Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland were driven to distraction by Confederate cavalry and irregulars. Like many in the U.S. Army, they were coming to the realization of how hasty and in error the McClellan clique had been in resisting the raising of volunteer cavalry as seen by their own experience as well as McClellan's failure in the Peninsula Campaign. The federal government had already put out a call to the states in the summer of 1862 for cavalry regiments, but they were just recently being raised and were not yet active in sufficient numbers.[15]

Initial issue

In response to John Hunt Morgan's October 1862 raid, Rosecrans sent the brigade in pursuit. In an effort to move faster, the brigade mounted mule wagons. The brigade nearly caught Morgan, but when they entered the last Confederate bivouac, Morgan had escaped. In this effort, John T. Wilder served as the commander of the 17th Indiana, one of the component regiments in the brigade.

On 22 December 1862 in Gallatin, Tennessee, John T. Wilder took over command of the brigade which at that time consisted of the 92nd and 98th Illinois Infantry Regiments, the 17th, 72nd, and 75th Indiana Infantry Regiments, and the 18th Indiana Battery of Light Artillery.[16] His initial combat mission was to pursue another of Morgan's raids into Kentucky intended to sever the Army of the Cumberland's primary supply line. Lacking sufficient cavalry to screen his army as he moved south toward what would be the Battle of Stones River as part of the Stones River Campaign, Rosecrans again had to use infantry to chase off Morgan. Trying to speed their movement, these infantry units deployed partially by rail. Wilder also unsuccessfully tried to replicate the use of mule-drawn wagons with the addition of men mounting the mules pulling the wagons.[17] Unfortunately, they still traveled the majority of the pursuit on foot over unpaved roads. Despite the use of rail and wagons to speed up the pursuit, the mission was a failure with Morgan's command escaping at the Rolling Fork River.[18] The difference in speed between cavalry and infantry made the pursuit near impossible.

As a result of the failure, Rosecrans and his subordinates revisited the experiment with wagons from the October events and realized the solution to their problems was the early role of dragoons as mounted infantrymen.[19] Several times, Rosecrans wrote to the Union General-in-Chief Major General Henry Wager Halleck stating his desire to convert or establish units of mounted infantry and asking for authorization to purchase or issue enough tack to outfit 5,000 mounted infantry.[20] He believed that he needed to outfit all of his cavalry with repeating weapons. When he felt he was not being heard, he went over Halleck directly to War Secretary Edward M Stanton. In a dispatch from 2 February, he explained his reasons to Secretary Stanton:

Murfreesborough, Tenn., February 2, 1863—12 m.

Hon. E. M. Stanton: I telegraphed the General-in-Chief that two thousand carbines and revolving rifles were required to arm our cavalry. He replied as if he thought it a complaint. I telegraphed you also, to prevent misunderstanding. I speak for the country when I say that 2,000 effective cavalry will cost the support of near $4,000—say $5,000—per day. The power of these men will be doubled by good arms. Thus would be saved $5,000 per day. But this is the smallest part of our trouble. One rebel cavalryman takes on an average 3 of our infantry to watch our communications, while our progress is made slow and cautious. We command the forage of the country only by sending large train guards. It is of prime necessity in every point of view to master their cavalry. I propose to do this, first, by so arming our cavalry as to give it maximum strength; secondly, by having animals and saddles temporarily to mount infantry brigades for marches and enterprises. We have now 1,000 cavalrymen without horses, and 2,000 without arms. We don’t want revolvers so much as light revolving rifles. This matter is so clearly in my mind of paramount public interest that I blush to think it necessary to seem to apologize for it. I do hope the Government will have confidence enough in me to know I never have asked, and never will ask, anything to increase my personal command. Had this been understood when I went with Blenker’s division, this nation might have been spared millions of blood and treasure.

W. S. ROSECRANS, Major-General.[21]

This stepping out of the chain of command seemed to work as it drew a quick response from Halleck promising the "best arms" and "superior arms" as soon as they became available from the factories.[22] Of note, Halleck reminded Rosecrans that "you are not the only general who is urgently calling for more cavalry and more cavalry arms" and that "Grant, Sibley, Banks, Hunter, Foster, Dix, and Schenck" all wanted more "more cavalry."[23]

Conversion to mounted infantry

In Wilder, an innovative and creative man, Rosecrans found an eager acolyte for mounted infantry as a solution. On 16 February 1863, Rosecrans authorized Wilder to mount his brigade.[24] The regiments also voted on whether to convert to mounted infantry. All but the 75th Indiana voted to change to mounted infantry. The 123rd Illinois who had wanted to become mounted infantry transferred from the 1st Brigade of the 5th Division of XIV Corps to replace them.[25] Through February 1863, Wilder obtained around a thousand mules to mount his command, not from the government but scavenged from the countryside. Due to the obstinacy of the mules, horses were frequently seized from local stocks in Tennessee as contraband and replaced the mules. Wilder boasted that it did “not cost the Government one dollar to mount my men.”[26]

In theory and in practice, the brigade would use their mounts to travel rapidly to contact, but upon engagement, the soldiers would fight dismounted. Due to this speed of deployment, the unit earned the nickname, "The Lightning Brigade", and it would prove the validity of its conversion in the campaign in the Western theater. They were also sometimes known as the "Hatchet Brigade" because they received long-handled hatchets to carry instead of cavalry sabers.

As well as mounting the command for faster deployment, Wilder felt that muzzle-loaded rifles were too difficult to use traveling on horseback. Like Rosecrans, he also believed that the superiority of repeating rifles were worth their price in return for the great increase in firepower. The repeating rifles also had the standoff range similar to the standard infantry Lorenzes, Springfields, and Enfields in use by the Army of the Cumberland. He felt the repeating and breech loading carbines in use by the Federal cavalry lacked the accuracy at long range that his brigade would need.[27]

While Rosecrans looked at the regiment's five-shot Colt revolving rifle that would equip other units in the Army of the Cumberland (particularly seeing action with the 21st Ohio Volunteer Infantry Union forces at Snodgrass Hill during the Battle of Chickamauga), Wilder was initially opting for the Henry repeating rifle as the proper weapon to arm his brigade. In early March, Wilder arranged a proposal for New Haven Arms Company (which later became famous as Winchester Repeating Arms) to supply his brigade with the sixteen-shot Henry if the soldiers paid for the weapons out of pocket. He had received backing from banks in Indiana on loans to be signed by each soldier and cosigned by Wilder. New Haven could not come to an agreement with Wilder despite the financing.[28][29]

After attending a promotional demonstration by Christopher Spencer for the Army of the Cumberland of his Spencer repeating rifle, Wilder proposed the Henry arrangement to Spencer. Spencer agreed and got the Ordnance Department to send a shipment to the Army of the Cumberland.[30] The majority of the shipment armed all men of the brigade.

The brigade's new weapon used a seven rimfire-cartridge tubular magazine that came through the butt. This rifle's increase in firepower would quickly make it one of the most effective weapons in the Civil War. With new mounts and new weapons, the brigade worked out new tactics. Alongside the Army of the Cumberland's other mounted infantry units, Wilder developed new training and tactics through May and June 1863.[31] By the middle of the latter month, the brigade's soldiers had realized the advantages the breech-loading repeating rifle held over the muzzleloader, and they exuded confidence in themselves, their leaders, their new tactics, and their treasured new weapons.[32]

Conflicting visions

In his 2002 thesis, Harbison illustrates the disconnect between Rosecrans' and Wilder's expectations.[33] Rosecrans appears to have envisioned a mounted rifle organization similar to those in the U.S. Army. These units were armed with rifles and fought on foot (with the rifle giving them a greater range of lethality) yet still performed the traditional cavalry roles of scouting enemy weaknesses and location, security of the flanks or rear the parent command, countering enemy cavalry, countering enemy infantry attacks, being a mobile reserve, inflicting the coup de grace to a faltering enemy, covering one's own retreat, and pursuit of a retreating foe. As such, when the carbines of the regular cavalry became rifled, these units were converted to Dragoons and eventually cavalry. Wilder saw the organization as an infantry formation with the basic roles of attack and defense. In fact, to preclude them being mistaken for cavalry, Wilder had the brigade remove the yellow cloth tapes from the outseam of the standard riding trousers which had been issued from the quartermasters.[34][lower-roman 1][35] Wilder stressed to his regiments that the mounts were a means of moving faster and that they were infantry. As such none of the training involved scouting and screening.

Tullahoma Campaign

Hoover's Gap

On June 23, 1863, Rosecrans deployed forces to feign an attack on Shelbyville while massing forces against Braxton Bragg's right.[36] His troops moved out toward Liberty, Bellbuckle, and Hoover's Gaps through the Highland Rim (near Beechgrove, Tennessee).[37] On June 24 in pouring rain that would persist for 17 days (Union soldiers spread the humorous rumor during the campaign that the name Tullahoma was a combination of the Greek words "tulla", meaning "mud", and "homa", meaning "more mud".)[38][39] Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's men, spearheaded by Colonel John T. Wilder's "Lightning Brigade",[40] made for Hoover's Gap. The brigade showed the advantage of their speed despite the weather by reaching the gap nearly 9 miles ahead of Thomas's main body.Despite orders from the divisional commander, General Joseph J. Reynolds to fall back to his infantry, which was still six miles away, Wilder decided to take and hold the position.[41]

The command surprised Confederate Colonel J. Russell Butler's 1st (3rd) Kentucky Cavalry Regiment at the entrance of the gap.[42][43][lower-roman 2] After skirmishing briefly and withdrawing under pressure, the rebels were unable to reach the gap before the better-fed horses of the Lightning Brigade. The Kentuckians fell apart as a unit and, unluckily for the Confederates, failed in their cavalry mission to provide intelligence of the Union movement to their higher headquarters. Although Wilder's main infantry support was well behind his mounted brigade and his division commander Major General Joseph J. Reynolds had directed him to fall back to the main force after contact, he determined to continue pushing through to seize and hold the Gap before the Confederate reinforcements could prevent him. The brigade drove the 1st Kentucky through the entire seven mile length of Hoover's Gap. At the other end, they were met with artillery fire and found out that the brigade and its one battery were outnumbered four-to-one.[44][29] The brigade had met Brig. Gen. William B. Bate's brigade of Maj. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart's division.

Wilder entrenched on the hills south of the gap and determined to hold this extremely advanced position.[45] Bate's brigade, supported by Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson's brigade and some artillery, assaulted Wilder's position, but was driven back by the concentrated fire of the Spencers, losing 146 killed and wounded (almost a quarter of his force) to Wilder's 61. Due to the heavy volume of fire he received from the brigade, Bate initially thought he was outnumbered five-to-one.[46]

Colonel James Connolly, commander of the 123rd Illinois, wrote:

As soon as the enemy opened on us with their artillery we dismounted and formed line of battle on a hill just at the south entrance to the "Gap," and our battery of light artillery was opened on them, a courier was dispatched to the rear to hurry up reinforcements, our horses were sent back some distance out of the way of bursting shells, our regiment was assigned to support the battery, the other three regiments were properly disposed, and not a moment too soon, for these preparations were scarcely completed when the enemy opened on us a terrific fire of shot and shell from five different points, and their masses of infantry, with flags flying, moved out of the woods on our right in splendid style; there were three or four times our number already in sight and still others came pouring out of the woods beyond. Our regiment lay on the hill side in mud and water, the rain pouring down in torrents, while each shell screamed so close to us as to make it seem that the next would tear us to pieces. Presently the enemy got near enough to us to make a charge on our battery, and on they came; our men are on their feet in an instant and a terrible fire from the "Spencers" causes the advancing regiment to reel and its colors fall to the ground, but in an instant their colors are up again and on they come, thinking to reach the battery before our guns can be reloaded, but they "reckoned without their host," they didn't know we had the "Spencers," and their charging yell was answered by another terrible volley, and another and another without cessation, until the poor regiment was literally cut to pieces, and but few men of that 20th Tennessee that attempted the charge will ever charge again. During all the rest of the fight at "Hoover's Gap" they never again attempted to take that battery. After the charge they moved four regiments around to our right and attempted to get in our rear, but they were met by two of our regiments posted in the woods, and in five minutes were driven back in the greatest disorder, with a loss of 250 killed and wounded.[47]

After a long day of combat at 1900, the brigade's morale was uplifted by the arrival of a fresh battery at the gallop, which meant the XIV Corps were close behind. A half hour later, the Corps' main infantry units arrived to secure the position against any further assaults. The corps commander, General Thomas, shook Wilder's hand and told him, "You have saved the lives of a thousand men by your gallant conduct today. I didn't expect to get to this gap for three days."[48] Rosecrans also arrived on the scene. Rather than reprimand Wilder for disobeying orders, he congratulated him for doing so, telling him it would have cost thousands of lives to take the position if he had abandoned it.[49]

On June 25, Bate and Johnson renewed their attempts to drive the Union men out of Hoover's Gap but failed against the Lightning Brigade now with its parent division and corps. Rosecrans brought the forward movement of the Army of the Cumberland to a halt as the roads had become quagmires. Bragg took no effective action to counter Rosecrans because his cavalry commanders were not relaying intelligence to him reliably—Forrest was not informing of the weak nature of the Union right flank attack and Wheeler failed to report the movement of Crittenden's corps through Bradyville and toward Bragg's rear.[50]

As the Lighting Brigade and the 5th Division held at Hoover's Gap, Bragg soon came to realize the threat of Thomas. Meanwhile, Rosecrans shifted his forces to reinforce Thomas at the gap.[51] Unfortunately for Bragg, infrequent direct communication with William J. Hardee, his corps commander who commanded Stewart left an ignorance of Bragg's campaign strategy. That ignorance coupled with a low opinion of his commander's intellect, led Hardee to do what "he deemed best for saving an army whose commander was an idiot."[52] That course was to order his battered troops under Stewart at Hoover's Gap to retreat towards Wartrace. His retreat served to only make Thomas's breakout more effective, leaving Bragg with his right flank gone. To keep his army together, he had to order Polk and Hardee to withdraw to Tullahoma on June 27.[53]

The raid

The Lightning Brigade reached Manchester at 8 a.m. on June 27, and the remainder of the division occupied the town by noon. On June 28, the brigade left on a raid to damage the railroad infrastructure in Bragg's rear, heading south toward Decherd, a small town on the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. The rain-swollen Elk River proved a significant obstacle, but they disassembled a nearby mill and constructed a raft to float their howitzers across. They defeated a small garrison of Confederates in Decherd, tore up 300 yards of track and a burned the railroad depot filled with Confederate rations. The next morning they rode into the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains, reaching the town of Sewanee where they destroyed a branch rail line. Although pursued by a larger Confederate force, the Lightning Brigade was back in Manchester by noon, June 30. They had not lost a single man on their raid.[54]

The effectiveness of the brigade led to an operational detachment from the division command while maintaining an administrative link to Reynold's division. Operationally, the brigade would act independently as a mobile reserve for the army.

With his corps commanders unnerved by the Lightning Brigade's raid, at 3 p.m. on June 30, Bragg issued orders for a nighttime withdrawal from fortifications in Tullahoma across the Elk River. By leaving before the Union assault, Bragg gave up an opportunity to inflict potentially serious damage on the Army of the Cumberland.[55] Initially positioned below the Elk River, Hardee and Polk felt they should retreat farther south, to the town of Cowan. In turn, their loss of nerve passed to Bragg who deemed Cowan indefensible on July 2. Without consulting his corps commanders, on July 3 Bragg ordered a retreat to Chattanooga. The army crossed the Tennessee River on July 4; a cavalry pursuit under Phil Sheridan was not successful in trapping the rear guard of Bragg's army before they crossed the river. All the Confederate units had encamped near Lookout Mountain by July 7.[56]

Chickamauga Campaign

Use of mounted infantry was developing and would see further development through the Chickamauga Campaign. While Wilder's brigade was the only mounted infantry unit of its size, several other regiments had converted to mounted infantry. Some had just been mounted while others had also received Spencer rifles, like the 39th Indiana, others had received Henrys, Colt Revolver rifles or Spencer carbines.[57] Because it was a full brigade, and especially after the addition of a fifth regiment, the 92nd Illinois, the Lightning Brigade found itself operating as an independent corps-level, or even army-level, asset. While remaining administratively under the control of Reynolds' 4th Division in Thomas' XIV Corps, Wilder frequently received tasking from corps commanders, and even Rosecrans himself.[58]

Second Battle of Chattanooga

(August 21 – September 8, 1863)

Having driven Confederate forces from middle Tennessee, the Army of the Cumberland paused to refit and replenish their units. Rosecrans did not immediately pursue Bragg and "give the finishing blow to the rebellion" as Stanton urged. He paused to regroup and study the difficult choices of pursuit into mountainous regions. Rosecrans tried to continue his war of maneuver and get around Bragg's flank to threaten his rear and force him to abandon Chattanooga vice taking it in a pitched battle.[59]

On August 16, 1863, Rosecrans launched his campaign to take Chattanooga, Tennessee. The Lighting Brigade (now with an added regiment the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry as of 10 July) played a crucial role in this campaign.[60][61] He sent the Lightning Brigade to General Crittenden's XXI Corps to conduct deception operations along the bank north of the Tennessee River Chattanooga. In company with William B. Hazen's infantry, George D. Wagner's, and Robert H. G. Minty's cavalry brigade, their mission was to sprint ahead of Crittenden's Corps to the Tennessee River, and visibly show its presence to the Confederate cavalry screening the south bank. The remainder of the corps would spread out across the Cumberland Plateau heading north of Chattanooga, while the Rosecrans' other two corps crossed the river below Chattanooga and Bragg.[62] Once the other corps were safely across the river, the XXI Corps would fall in behind them leaving the four brigades to keep Bragg focused across the river to the north bank. The four brigades would patrol the river, make as much noise as possible, and feign river crossing operations north of the city. That was what Bragg feared most, a crossing north of Chattanooga.

Wilder's brigade moved out from its headquarters on 16 August, ascending the Plateau and camping that night at Sewanee, near the University of the South. The brigade and Minty's cavalrymen led the advance. Those two brigades would move quickly to reach the river while Hazen and Wagner would make their best speed to follow.[63] The 92nd and its companions quickly worked their way towards the Tennessee River, through Dunlap, reaching Poe's Tavern,[64][lower-roman 3] to the northeast of Chattanoogas Ridge on August 20. The steep slopes of the Cumberland Plateau and Walden's Ridge were difficult terrain, and there was a dearth of forage, but the two brigades still made good time in their advance.[63]

At dawn on 21 August, the command moved to the Tennessee to begin their deception. Wilder and Minty divided the north bank between their brigades. The 92nd and its brigade mates covered southern side, from city to Sale Creek, and Minty's men from there north to the mouth of the Hiawassee River. Wagner and Hazen's brigades, traveling afoot were still crossing the mountains. Once they arrived, they would join the force already there to keep Bragg distracted.[65]

On arrival, Wilder and Minty divided the north bank between the brigades. The Lightning Brigade would cover from opposite the city to Sale Creek about eleven miles upstream. Minty would cover the sector further upstream. The idea was to keep the Rebels watching to the north and east. Wilder further divided his sector sending the 92nd and 98th Illinois with a section of the 18th Indiana Light Artillery (Capt. Eli Lilly's battery), ten miles up the Tennessee toward Minty to the ferry at Harrison's Landing. He kept the 123rd Illinois, 17th and 72nd Indiana with the rest of Lilly's Battery opposite the city.

Rosecrans had ordered the brigade to shell Chattanooga from the north bank of the Tennessee River to divert attention away from the flanking columns sent southwest of the city. Moving cautiously at first, scouts approached the river to appraise the state and location of Confederate forces. The men in the brigade opposite the city found some Confederate soldiers on the north bank, ignorant of the Union force approaching with the 123d Illinois capturing forty prisoners and a ferry. At Harrison's Landing, the 92nd and 98th Illimois found no meaningful forces save a single gun in a small fort on the south bank that was quickly destroyed by the accompanying section of Lilly's Battery.

Next, opposite the city, Wilder brought forward Captain Lilly with his remaining two section and set them up on high ground about one half mile from the river. His first targets his artillery attacked were the Dunbar and Paint Rock, two steamers docked at the Chattanooga Wharf. They were quickly sunk. Wilder ordered Lilly to begin shelling the town. The shells caught many soldiers and civilians in town in church observing a day of prayer and fasting. The bombardment created a great deal of consternation amongst the Confederates.[66]

The three regiments and Lilly's men began shifting positions back and forth to keep the Rebels in the city confused. The 92nd and 98th, after securing the ferry at Harrison's Landing, began trying to keep the Confederates on the opposite bank distracted. When Wagner and Hazen's brigades arrived on August 29, some of Hazen's dismounted infantry joined the 92nd and 98th at Harrison's landing to aid in the misdirection.[67] The deception operation included the 92nd and its compatriots faking boat construction by hammering, sawing, and tossing bits of lumber into the river at Harrison's Landing so that it would float downstream to Chattanooga.[68] The whole brigade also began a nightly ritual of building numerous campfires to imitate the look of numerous regimental camps.[69] The whole operation also benefited from the fact that the local population north of the river in Eastern Tennessee on the Cumberland Plateau was strongly Unionist which meant that any Rebels operating there would be quickly reported back to the Army of the Cumberland; in light of this Bragg and no cavalry screen patrolling that could see through the deception.

Continuing periodically over the next two weeks, the shelling and movements within sight of Confederate lookouts on the south bank helped keep Bragg's attention to the northeast while the bulk of Rosecrans's army crossed the Tennessee River well west and south of Chattanooga. The diversion was successful, with Bragg concentrating his army east of Chattanooga. On the morning of September 5, the rest of the Wilder and Minty were themselves tricked when Bragg's forces faked preparations to cross the river to the north side to attack.[70] They quickly concentrated their forces to contest the crossing, but by the next day, they had figured out that it was a ruse to fix them in one place.[71][72]

When Bragg learned on September 8 that the Union army was in force southwest of the city, he had already decided to abandon the city (Rosecran's goal) and was planning to withdraw to a more defensible position further south. He sped up his withdrawal and marched his Army of Tennessee into Georgia.[73] Bragg's army marched down the LaFayette Road and camped in the city of LaFayette.[66] Wilder did not pursue the retreating enemy because that was a cavalry role, but he did pass on reports from local inhabitants to Rosecrans deceived him into believing Bragg was fleeing in chaos to Dalton or Rome, Georgia.[74]

On September 9, the brigade received orders to cross the river at Friar's Island, two miles downstream from Harrison's Landing, and enter Chattanooga.[72] The river crossing and movement to Chattanooga occupied the 9th and 10th.[75][76]

Skirmish at Ringgold

(September 11–12, 1863)

As Rosecrans moved his forces south and west, the heavily wooded and hilly terrain soon had 60 miles of separation between his three making mutual support nearly impossible. It gradually dawned on him that Bragg's Army was neither demoralized nor in disarray. It was not defeated. Bragg attacked General James S. Negley's isolated division of the Union XIV Corps, commanded by George H. Thomas, before Rosecrans could concentrate the rest of his army across Chickamauga Creek near Davis' Cross Roads. Negley retreated and met up with the rest of the XIV Corps. Thomas confirmed to Rosecrans that the rebels were not falling back as they had previously believed but instead seemed to be massing for an imminent attack. Concerned about mutual support, Thomas and McCook made plans to shift their corps closer together to the north.[77]

Meanwhile, on 11 September, the Lightning Brigade, attached to Crittenden's[78] advanced from Lee and Gordon's Mill to Ringgold, GA. There it skirmished with and defeated Col. John S. Scott's brigade of John Pegram's Division of Forrest's Cavalry Corps and then drove off Confederate reinforcements. It returned to the mill by nightfall. The following morning, it was again ordered to advance to Ringgold. Four miles short of the town, it again ran into elements of Pegram's Division. After dispersing these units, Wilder found that Strahl's Brigade of Cheatham's Division of Polk's Corps had cut the brigade's route back to the mill. Although the Lightning Brigade was surrounded, the rebels unsure of its identity, size, and strength, did not press home an attack.[79][80]

At nightfall, the Wilder deceived the Confederates by spreading campfires over a large area to make the Confederates believe his force was much larger. He formed four of his regiments and the battery into a defensive perimeter and had the fifth, the 72nd Indiana look for an escape route. After successfully locating an exit, the brigade withdrew back to XXI Corps without the loss of a man.[81] As they rode away at dawn, they heard the rebels attacking their former encampment.[82]

Chickamauga

(September 19–20, 1863)

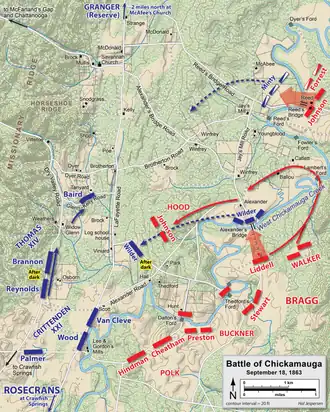

First encounter

Realizing that part of his force had narrowly escaped a Confederate trap, Rosecrans abandoned his plans for a pursuit and began to concentrate his scattered forces near Stevens Gap.[83] For the next four days, both armies attempted to improve their dispositions. Rosecrans continued to concentrate his forces, intending to withdraw as a single body to Chattanooga. By September 17, the three Union corps were now much less vulnerable to individual defeat. Reinforced with two divisions arriving from Virginia under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, and a division from Mississippi under Brig. Gen. Bushrod R. Johnson, Bragg decided to move his army northward on the morning of 18th and advance toward Chattanooga, forcing Rosecrans's army to fight or to withdraw. If Rosecrans fought, he risked being driven back into McLemore's Cove.[84]

The Lightning Brigade was sent to defend Alexander's Bridge over the Chickamauga on 17 September. The 92nd Illinois detached to protect the army's line of communication back to Chattanooga. The next day, 18 September, the Lightning Brigade blocked the crossing against the approach of W.H.T. Walker's Corps. Armed with Spencer repeating rifles and Capt. Lilly's four guns of the 18th Indiana Battery, the brigade held off a brigade of Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell's division,[85][86] which suffered 105 casualties against Wilder's superior firepower. Walker moved his men downstream a mile to Lambert's Ford, an unguarded crossing, and was able to cross around 1630, considerably behind schedule. Wilder, concerned about his left flank after Minty's loss of Reed's Bridge, withdrew the brigade to a new blocking position near the Viniard farm.[87][88] By dark, Bushrod Johnson's division had halted in front of Wilder's position. Walker had crossed the creek, but his troops were well scattered along the road behind Johnson.[89][90][91]

The first day

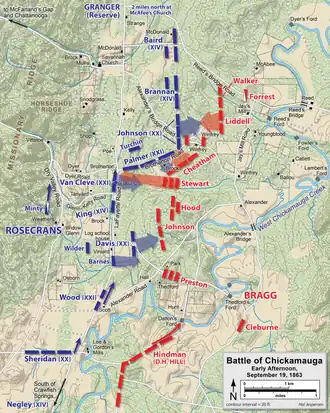

Although Bragg had achieved some degree of surprise, he failed to exploit it strongly. Rosecrans, observing the dust raised by the marching Confederates in the morning, anticipated Bragg's plan. He ordered Thomas and McCook to Crittenden's support, and while the Confederates were crossing the creek, Thomas began to arrive in Crittenden's rear area.[92][91][93]

Through the morning to midday of 19 September, the Lightning Brigade held its position as a reserve near Viniard farm slightly uphill and behind the main line. as the battle began. As the battle progressed, the front developed in a north south direction just west of Chickamauga Creek. Viniard farm was just right of the Union Center held by Maj. Gen. Alexander McDowell McCook's XX Corps.

At around 2 p.m., the Johnson's division (Hood's corps) forced Union Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis's two brigade division of the XX corps back across the LaFayette Road. Johnson to continue the advance with two brigades in line and one in reserve. On the right, Col. John Fulton's brigade routed King's brigade and linked up with Bate at Brotherton field. On the left, Crittenden sent the Lighting Brigade from its reserve position forward to assist Davis.[94]

As he advanced, Wilder saw a column of Brig. Gen. John Fulton's Brigade trying to Flank one of Davis' batteries. He sent the 123rd Illinois (Col. Monroe) and 72nd Indiana (Col. Miller) who promptly broke them and drove them off.[95] Soon, he noticed Brig. Gen. John Gregg's brigade moving through the woods on his left . He quick-marched Miller and Monroe back in line and all four regiments moved forward facing the woods across the fields at the Glenn House. The brigade opened an enfilading fire on the left flank of the dense mass of Rebel as they moved out of the woods into the open ground. There, they stopped the Rebels, and drove them back with heavy losses.[93] Gregg was seriously wounded and Johnson's division's advance halted. The brigade also repulsed Brig. Gen. Evander McNair's brigade, called up from the rear.[96] After the Confederates withdrew from the woods, the Lightning Brigade returned to its reserve position upslope behind XX Corps.[97]

As the battle continued, Hood's Corps pushed the Union line back north to the Viniard house with elements of the XXI Corps attacked by Hood's corps on the brigade's left. Davis' division was pushed back to the brigade's right where Sheridan's division pushed forward only to be stopped by Hood's onslaught. His units were pushed behind the brigade's line.[98] Hood's Corps advanced so close to Rosecrans's new headquarters at the Glenn Cabin leading to a significant risk of a Federal rout in this part of the line. At this point, once again, the Lighting Brigade's was sent to prevent a breakthrough. Reversing their position near the house to face right instead of left, they let Rebels advance so that their right flank was within 150 yards of their own position. The superior firepower from their Spencers enfiladed the right flank and drove the column to seek cover in a drainage ditch that ran parallel to the main battle line, but perpendicular to the Lightning Brigade's line. This galling fire was added to by the deadly effectiveness of Lilly's battery raking the ditch with canister.[99] Eventually, they sent the Confederate column into retreat out of range of their Spencers and Lilly's canister.[100]

At 5 p.m., the 92nd Illinois, who had been hotly engaged themselves further north, rejoined the brigade and took position on the slope to the left.[97]

The second day

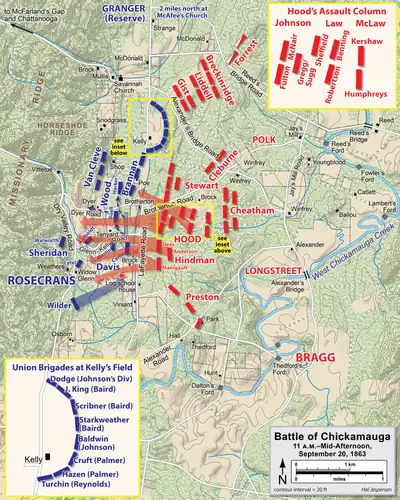

At dawn, on September 20, Rosecrans personally ordered the brigade to take position west across Dry Valley Road on the crest of the east slope of Missionary Ridge at the right end of XX Corps and to report to Maj. Gen. McCook.

Starting about 0930 on 20 September, the battle resumed primarily to the left (north) of the brigade. The 39th Indiana had been detached Willich's 1st Brigade from Johnson's Second Division of McCook's XX Corps and was acting as an independent mounted infantry army-level asset. At 09:30, Rosecrans ordered them to report to Wilder. When they arrived fifteen minutes later, the brigade now had approximately 2000 troops armed with Spencer rifles.[101]

Bragg soon ordered his entire line to advance. By 1100, Longstreet had assembled a column of 10,000 men to attack the Union center.[102] The attack succeeded aided by a gap left by a rearranged Union line.

As the attack rapidly turned into a Union rout in the center around 1300, the Lightning brigade was ordered to counterattack against Brig. Gen. Arthur Manigault's brigade of Hood's Division from its reserve position. It launched a strong advance with its superior firepower, driving the enemy around and through what became known as "Bloody Pond". The rush of the Lightning Brigade surprised the advancing gray columns. With Lilly's guns and the Indiana and Illinois regiments' Spencers sweeping the field, they stopped the Confederates cold.[26] The melting Rebel formations drew the brigade into counterattack, with Wilder's men routing one enemy regiment, the 34th Alabama, and forcing the 28th Alabama to fall back as well as freezing their division's forward movement. In short order, the brigade had seen off Manigault's brigade, driven back Hood's division, and taken 200 prisoners.[101] The Rebels attacked the brigade four more times yet never closed within 50 yards before breaking and fleeing under the heavy firepower.[103] Having blunted the Confederate advance, Wilder planned to capitalize on this success by attacking the flank of Hood's column. His plan was to attack through Hood on Longstreet's left flank and on to Thomas.[104]

The opportunity was lost when Wilder had to see to Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana who proclaimed that the battle was lost and demanded to be escorted to Chattanooga.[105] Some controversy exists on whether Dana ordered Wilder to not make the attack, but retreat. In the time that Wilder took to arrange a small detachment to escort him back to safety, the opportunity for a successful attack was lost and he ordered his men to withdraw to the west.[106][107][108]

The brigade remained cut off on the other side of Dyer Road south of Thomas's final position on Horseshoe Ridge. At 1630, Wilder received the order to retreat to Chattanooga. After nightfall, the brigade mounted and withdrew. As they fell back, they collected the details from the 92nd Illinois and set a screening line across Dyer Road as it passed through the gap from the hill to the mountain with the Vittetoe house in its center. They kept the road open and the rebels at a distance overnight during Thomas' retreat from Snodgrass Hill.[109]

Through the battle, the brigade had performed exceedingly well making good use of their Spencers. They were one of the few units south of Horseshoe Ridge that did not panic and retreat but successfully attacked. At dawn, once they realized no more of the troops on Snodgrass Hill would be coming up the road, the brigade departed the field intact and in good order.[110]

Reorganization and disestablishment

On September 21, Rosecrans's army withdrew to the city of Chattanooga and took advantage of previous Confederate works to erect strong defensive positions. However, the supply lines into Chattanooga were at risk, and the Confederates soon occupied the surrounding heights and laid siege upon the Union forces. The brigade was tasked with patrolling and scouting to the west of the city down the Tennessee, to counter Wheeler's cavalry. From this point on, the regiments of the brigade were used frequently in the cavalry roles of scouting and screening.[111]

The Union forces were quickly reorganized. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was appointed commander of the newly created Military Division of the Mississippi, bringing all of the territory from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River (and much of the state of Arkansas) under a single commander for the first time. On 19 October, Grant relieved the demoralized Rosecrans. He selected Thomas to command the Army of the Cumberland.

In October, the Army of the Cumberland reorganized. In this shuffle, the Lightning Brigade was gradually shifted into the cavalry of the army.[112] The 98th Illinois and the 17th Indiana were assigned to the 2nd Brigade of the 2nd Division of the Cavalry Corps. The 123rd Illinois and the 75th Indiana were transferred to the 3rd Brigade of the 2nd Division of the Cavalry Corps. The 92nd Illinois was used as an army asset with its companies serving as supply line security and command escorts.[113]

See also

Notes/References/Sources

Notes

- ↑ Brewer, Harbison, and Maurice are three well-written theses inre the Lightning Brigade. Additionally, Brewer and Harbison bring a trained military eye to their analyses of operations involving the Lightning brigade. All three use a lot of the same original sources as this Wiki article.

- ↑ This was the regiment originally recruited by Lincoln's brother -in-law, Benjamin H Helm, who would soon fall to mortal wounds at Chickamauga

- ↑ The tavern, built in 1819, was home to Hamilton County's first courthouse and government seat.

References

- ↑ Adj. Gen Indiana.Report, Vol. 2, p. 145–157.

- ↑ Adj. Gen Indiana.Report, Vol. 2, p. 665–673.

- ↑ Adj. Gen Indiana.Report, Vol. 3, p. 431–432.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/1, p. 483.

- ↑ Atkins (1907); Baumgartner (1997); Dyer (1908).

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1085; Reunion Association (1875), p. 22.

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1088.

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1098.

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1125; Regimental Association (1913), p. 47.

- ↑ Adj. Gen Indiana.Report, Vol. 4, p. 344–371.

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1145; McGee (1882), p. 13, 20-26.

- ↑ Adj. Gen Indiana.Report, Vol. 6, p. 163–181.

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1116; Rowell (1975), p. 15.

- ↑ Adj. Gen Indiana.Report, Vol. 7, p. 754–757.

- ↑ Lamers (1961), p. 34, 46, 50; Starr (1985), p. 82.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 20/1, p. 179Organization of the ... Army of the Cumberland, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, U.S. Army, Commanding, December 26, 1862-January 5, 1863, pp.174-182

- ↑ Living History (2020).

- ↑ Baumgartner (1997), p. 15; Duke (1906), p. 71.

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1089.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 20/2, p. 326,Rosecrans to Halleck, 14 January 1863

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, p. 34,Rosecrans to Stanton, 2 February 1863

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, p. 38,Halleck to Rosecrans, 3 February 1863

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, p. 37-38,Halleck to Rosecrans, 3 February 1863

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, p. 74,Special Orders No. 44, 16 February 1863

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/1, p. 457-461,Wilder Report (1st Bde, 4th Div. XIV Corps), 11 July 1863

- 1 2 Garrison, Graham, Parke Pierson, and Dana B. Shoaf (March 2003) “LIGHTNING AT Chickamauga.” America’s Civil War V.16 No.1, p. 53.

- ↑ Baumann (1989), p. 224.

- ↑ Jordan, Hubert (July 1997) “Colonel John Wilder’s Lightning Brigade Prevented Total Disaster.” America’s Civil War V.16 No.1, p. 44.

- 1 2 Leigh, Phil (December 25, 2012) "Colonel Wilder's Lightning Brigade," The New York Times, p. 1.

- ↑ Korn (1985), p. 21; Williams (1935).

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1125; Reece (1900), p. 538.

- ↑ Stuntz, Margaret L. (July 1997) “Lightning Strike at the Gap.” America’s Civil War, p. 56.

- ↑ Harbison (2002), p. 92-93.

- ↑ Brewer (1991), p. 78; Harbison (2002), p. 93; Maurice (2016), p. 37.

- ↑ Stuntz, Margaret L. (July 1997) “Lightning Strike at the Gap.” America’s Civil War, p. 56.

- ↑ Frisby (2000), p. 420.

- ↑ Sunderland (1969), p. 74.

- ↑ Eicher, McPherson, & McPherson (2001), p. 496.

- ↑ Korn (1985), p. 29.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/1, p. 413,Report No. 3, Organization of troops in Department of the Cumberland, 30 June 1863

- ↑ Kennedy (1998), p. 225; Williams (1935), p. 182.

- ↑ NPS Hoover's Gap.

- ↑ Smith (2005), p. 191-194.

- ↑ Connolly (1863), p. 1.

- ↑ Kennedy (1998), p. 225.

- ↑ Williams (1935), p. 183.

- ↑ Connolly (1863), p. 1; Connolly (1959), p. 29.

- ↑ Connelly (1971), p. 126–27; Korn (1985), p. 24–26; Woodworth (1998), p. 21–24.

- ↑ Cozzens (1992), p. 27; Leigh, Phil (December 25, 2012) "Colonel Wilder's Lightning Brigade," The New York Times, p. 1.

- ↑ Connelly (1971), p. 126; Korn (1985), p. 28; Woodworth (1998), p. 28–30.

- ↑ Connelly (1971), p. 127–28; Korn (1985), p. 28; Woodworth (1998), p. 31–33.

- ↑ Connelly (1971), p. 126; McWhiney (1991), p. 337; Woodworth (1998), p. 33.

- ↑ Connelly (1971), p. 128–29; Connolly (1959), p. 150; Woodworth (1998), p. 34.

- ↑ Woodworth (1998), p. 36–38.

- ↑ Connelly (1971), p. 130–32; Hallock (1991), p. 125-140; Lamers (1961), p. 284–285; Korn (1985), p. 30; Woodworth (1998), p. 38–40.

- ↑ Connelly (1971), p. 133; Lamers (1961), p. 285–288; Woodworth (1998), p. 40-42.

- ↑ Sunderland (1984), p. 11.

- ↑ Harbison (2002), p. 92.

- ↑ Woodworth (1998), p. 53-54.

- ↑ Dyer (1908), p. 1085.

- ↑ Stuntz, Margaret L. (July 1997) “Lightning Strike at the Gap.” America’s Civil War, p. 57.

- ↑ Baumgartner (1997), p. 245.

- 1 2 Atkins (1909), p. 6.

- ↑ Harbison (2002), p. 53.

- ↑ Harbison (2002), p. 53-54; Woodworth (1998), p. 54.

- 1 2 NPS Chickamauga.

- ↑ Baumgartner (1997), p. 245-246.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/1, p. 446.

- ↑ Reunion Association (1875), p. 99-100.

- ↑ Reunion Association (1875), p. 103.

- ↑ Maurice (2016), p. 16.

- 1 2 U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/1, p. 425.

- ↑ Martin (2011), p. 268-274.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/3, p. 164-165, 365.

- ↑ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Dec 2006, p. 46–50.

- ↑ Kennedy (1998); Williams (1936), p. 25-27.

- ↑ Cozzens (1992), p. 65–75.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/1, p. 445-491,Wilder Report (1st Bde, 4th Div. XIV Corps), 10 November 1863

- ↑ Jordan, Hubert (July 1997) “Colonel John Wilder’s Lightning Brigade Prevented Total Disaster.” America’s Civil War V.16 No.1, p. 1.

- ↑ Maurice (2016), p. 21.

- ↑ Sunderland (1969), p. 145.

- ↑ Baumgartner (1997), p. 164-180; Sunderland (1984), p. 62-63.

- ↑ Lamers (1961), p. 313; Robertson, Blue & Gray, Jun 2006, p. 48-51.

- ↑ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Jan 2006.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/2, p. 251Report of Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell, C.S. Army, commanding division, October 10, 1863, pp.251-255

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/1, p. 449-453,Report of Col. Abram O. Miller, 72nd Indiana Infantry, commanding, 1st Brigade (Mounted Infantry), 28 September 1863

- ↑ Cozzens (1992), p. 198; Tucker (1961), p. 112–17; Woodworth (1998), p. 83.

- ↑ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Jun 2007, p. 44–45.

- ↑ Cozzens (1992), p. 199–200; Esposito (1962), p. 112; Kennedy (1998), p. 230.

- ↑ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Oct 2007, p. 44–45.

- 1 2 Eicher, McPherson, & McPherson (2001), p. 581.

- ↑ Esposito (1962), p. 112; Lamers (1961), p. 322; Tucker (1961), p. 118; Woodworth (1998), p. 85.

- 1 2 Robertson, Blue & Gray, Dec 2006, p. 43-45.

- ↑ Eicher, McPherson, & McPherson (2001), p. 582–583.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/1, p. 447,Report of Col. J. T. Wilder Report (1st Bde, 4th Div. XIV Corps), 10 November 1863

- ↑ Cozzens (1992), p. 196, 199–200, 214; Korn (1985), p. 48; Tucker (1961), p. 166, 172–73; Woodworth (1998), p. 92.

- 1 2 U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/1, p. 451-452,Report of Col. Abram O. Miller, 72nd Indiana Infantry, commanding, 1st Brigade (Mounted Infantry), 28 September 1863

- ↑ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Jun 2007, p. 47-51.

- ↑ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 30/1, p. 448,Report of Col. J. T. Wilder Report (1st Bde, 4th Div. XIV Corps), 10 November 1863

- ↑ Cozzens (1992), p. 218–24, 259–62; Korn (1985), p. 48; Lamers (1961), p. 331; Tucker (1961), p. 170–72, 174; Woodworth (1998), p. 93.

- 1 2 Johnson & Buel, The Tide Shifts Battles and Leader, vol. III (1887), p. 658-659n.

- ↑ Robertson (2010), p. 125.

- ↑ Johnson & Buel, The Tide Shifts Battles and Leader, vol. III (1887), p. 659n.

- ↑ Maurice (2016), p. 78.

- ↑ Woodworth (1998), p. 119.

- ↑ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Oct 2007, p. 46-49.

- ↑ Eicher, McPherson, & McPherson (2001), p. 589.

- ↑ Cozzens (1992), p. 376–90, 392–96; Lamers (1961), p. 352; Tucker (1961), p. 288–99, 315–17; Woodworth (1998), p. 118–19.

- ↑ Baumgartner (1997), p. 65, 67-68, 299; Sunderland (1984), p. 90; Woodworth (1998), p. 144; Williams (1935), p. 191-192.

- ↑ Williams (1935), p. 192-193.

- ↑ Williams (1935), p. 194-197.

- ↑ Starr (1985), p. 340-342.

- ↑ Sunderland (1984), p. 200.

Sources

- Atkins, Smith Dykins (1907). "Chickamauga : Useless, Disastrous Battle". Woman's Relief Corps, G.A.R. Talk Mendota, IL February 22, 1907 (PDF). Grand Army of the Republic. p. 24. OCLC 906602437. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Atkins, Smith Dykins (1909), "Remarks at Wilder's Brigade Reunion", Wilder's Brigade Reunion Effingham, IL: Sept. 17, 1909, Reunion Association, Ninety-Second Illinois, p. 12, OCLC 35004612

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Baumgartner, Richard A. (1997). Blue Lightning: Wilder's Mounted Brigade in the Battle of Chickamauga. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-1-885033-35-2. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Baumann, Ken (1989). Arming the Suckers, 1861-1865: A Compilation of Illinois Civil War Weapons. Dayton, OH: Morningside House. p. 237. OCLC 20662029.

- Brewer, Richard J, MAJ USA (1991). The Tullahoma Campaign: Operational Insights (PDF). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Theses 1991 (Thesis Submission ed.). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Defense Technical Information Center. p. 199. OCLC 832046917. DTIC_ADA240085. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Connolly, James A (1959). Paul M. Angle (ed.). Three Years in the Army of the Cumberland: The Letters and Diary of Major James A. Connolly. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780527190002. OCLC 906602437. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Connolly, James A (1863). "Primary Sources: The Road to Chickamauga". Washington, DC: American Battlefield Trust.

- Connelly, Thomas L (1971). Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee 1862–1865. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2738-8. OCLC 1147753151.

- Cozzens, Peter (1992). This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252065941. OCLC 53818141.

- Duke, Basil W. (1906). Morgan's Cavalry. New York, NY: Neale Pub. Co. OCLC 35812648.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Dyer, Frederick H (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. Des Moines, IA: Dyer Pub. Co. ASIN B01BUFJ76Q.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Eicher, David J.; McPherson, James M.; McPherson, James Alan (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-1846-9. OCLC 892938160.

- Esposito, Vincent J., Col. USA (1962). West Point Atlas of the Civil War. New York, NY: Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 5890637.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Frisby, Derek W. (2000). Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T. (eds.). Tullahoma Campaign. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Vol. IV. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9781576070666. OCLC 872478436.

- Garrison, Graham; Pierson, Parke; Shoaf, Dana B. (March 2003). "Lightning at Chickamauga". America's Civil War. Historynet LLC. 16 (1): 46–54. ISSN 1046-2899. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Hallock, Judith Lee (1991). Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Volume II (PDF). Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780585138978. OCLC 1013879782. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Harbison, Robert E, MAJ USA (2002). Wilder's Brigade in the Tullahoma and Chattanooga Campaigns of the American Civil War (PDF). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Theses 2002 (Thesis Submission ed.). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Defense Technical Information Center. p. 122. OCLC 834239097. DTIC_ADA406434. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Johnson, Robert Underwood; Buel, Clarence Clough (1887). Robert Underwood Johnson; Clarence Clough Buel (eds.). The Tide Shifts. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate officers: Based upon "The Century War Series". Vol. III. New York City: The Century Company. p. 778. OCLC 48764702.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jordan, Hubert (July 1997). "Battle of Chickamauga: Colonel John Wilder's Lightning Brigade Prevented Total Disaster". America's Civil War. Historynet LLC. 10 (3): 44–49. ISSN 1046-2899. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 9780395740125. OCLC 60231712.

- Korn, Jerry (1985). The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 9780809448166. OCLC 34581283. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Lamers, William M. (1961). The Edge of Glory: A Biography of General William S. Rosecrans, U.S.A.. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World. ISBN 9780807123966. OCLC 906813341. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Leigh, Phil (December 25, 2012). "Colonel Wilder's Lightning Brigade". The New York Times.

- Martin, Samuel J. (2011). General Braxton Bragg, C.S.A. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 9780786459346. OCLC 617425048.

- Maurice, Eric (2016). "Send Forward Some Who Would Fight": How John T.Wilder and His "Lightning Brigade" of Mounted Infantry Changed Warfare (PDF). Graduate Thesis Collection. Indianapolis, IN: Butler University. p. 129. OCLC 959927116. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- McGee, Benjamin F., Sgt. of Co. I (1882). Jewell, William Ray, Lt. of Co. G (ed.). History of the 72d Indiana Volunteer Infantry of the Mounted Lightning Brigade (PDF) (1st ed.). LaFayette, IN: S. Vater & Co. p. 698. OCLC 35653923. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - McWhiney, Grady (1991). Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Volume I. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. hdl:2027/pst.000019424187. ISBN 9780817391850. OCLC 1013878393.

- Reece, J. N., Brig Gen, Adjutant General (1900). Seventy-Eighth Infantry Regiment (Three Year's Service) — One Hundred and Fifth Infantry Regiment (Three Year's Service). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois (1900-1902). Vol. V. Springfield, Ill.: Phillips Bros., State Printer. ISBN 9781333835699. OCLC 980498014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Regimental Association, Seventeenth Indiana (1913). Souvenir, the Seventeenth Indiana Regiment : a history from its organization to the end of the war, giving description of battles, etc., also list of the survivors (PDF). Elwood, IN: Seventeenth Indiana Regimental Association. p. 140. OCLC 3225723. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Reunion Association, Ninety-Second Illinois (1875). Ninety-Second Illinois Volunteers (PDF) (1st ed.). Freeport, IL: Journal Steam Publishing House and Book Bindery. p. 390. OCLC 5212169. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Robertson, William Glenn (2010). "Bull of the Woods? James Longstreet at Chickamauga". In Woodworth, Steven E. (ed.). The Chickamauga Campaign (Kindle). Civil War Campaigns in the West (2011 Kindle ed.). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780809385560. OCLC 649913237. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Robertson, William Glenn (January 2006). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Fall of Chattanooga". Blue & Gray Magazine. Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. XXIII (136). ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (June 2006). "The Chickamauga Campaign: McLemore's Cove - Bragg's Lost Opportunity". Blue & Gray Magazine. Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. XXIII (138). ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (December 2006). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Armies Collide". Blue & Gray Magazine. Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. XXIV (141). ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (June 2007). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Battle of Chickamauga, Day 1". Blue & Gray Magazine. Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. XXIV (144). ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (October 2007). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Battle of Chickamauga, Day 2". Blue & Gray Magazine. Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. XXV (146). ISSN 0741-2207.

- Rowell, John W. (1975). Yankee Artillerymen: Through the Civil War with Eli Lilly's Indiana Battery. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. p. 320. ISBN 9780870491719. OCLC 1254941.

- Smith, Derek (2005). The Gallant Dead : Union and Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811748728. OCLC 1022792759.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (1985). The War in the West, 1861–1865. The Union cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. III. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807112090. OCLC 769318010.

- Stuntz, Margaret L. (July 1997). "Lightning Strike at the Gap". America's Civil War. Historynet LLC. 10 (3): 50–57. ISSN 1046-2899. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Sunderland, Glenn W. (1969). Lightning at Hoover's Gap: the Story of Wilder's Brigade. London: Thomas Yoseloff. hdl:2027/pst.000024463898. ISBN 0498067955. OCLC 894765669.

- Sunderland, Glenn W. (1984). Wilder's Lightning Brigade and Its Spencer Repeaters. Washington, IL: Bookworks. ISBN 9996886417. OCLC 12549273.

- Terrell, William Henry Harrison, Adjutant General (1865). Roster of Officers [incl.] Indiana Regiments Sixth to Seventy-Fourth 1861-1865 (PDF). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana. Vol. II. Indianapolis, IN: W. R. Holloway, State Printer. pp. 145–157, 665–673. OCLC 558004259. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Terrell, William Henry Harrison, Adjutant General (1866). Roster of Officers [incl.] Indiana Light Batteries 1861-1865 (PDF). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana. Vol. III. Indianapolis, IN: Samuel R. Douglas, State Printer. pp. 431–432. OCLC 558004259. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Terrell, William Henry Harrison, Adjutant General (1866). Roster of Enlisted Men [incl.] Indiana Regiments Sixth to Twenty-Ninth 1861-1865 (PDF). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana. Vol. IV. Indianapolis, IN: Samuel R. Douglas, State Printer. pp. 344–371. OCLC 558004259. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Terrell, William Henry Harrison, Adjutant General (1866). Roster of Enlisted Men [incl.] Indiana Regiments Sixtieth to One Hundred and Tenth 1861-1865 (PDF). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana. Vol. VI. Indianapolis, IN: Samuel R. Douglas, State Printer. pp. 163–181. OCLC 558004259. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Terrell, William Henry Harrison, Adjutant General (1867). Roster of Enlisted Men [incl.] Indiana Light Batteries 1861-1865 (PDF). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana. Vol. VII. Indianapolis, IN: Samuel R. Douglas, State Printer. pp. 754–757. OCLC 558004259. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Tucker, Glenn (1961). Chickamauga: Bloody Battle in the West. Indianapolis, Ind.: Bobbs-Merrill Co. ISBN 978-1-78625-115-2. OCLC 933587418.

- U.S. War Department (1887). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. Nov. 1, 1862-Jan. 20, 1863. – Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XX-XXXII-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1887). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. Nov. 1, 1862-Jan. 20, 1863. – Correspondence, etc. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XX-XXXII-II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1889). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. Nov. 1, 1862-Jan. 20, 1863. – Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXIII-XXXV-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1889). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. January 21 – August 10, 1863. – Correspondence, etc. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXIII-XXXV-II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1899). Operations in Kentucky, Southwest Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Alabama, and North Georgia. August 11-October 19, 1863. – Part I Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXX-XLII-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1899). Operations in Kentucky, Southwest Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Alabama, and North Georgia. August 11-October 19, 1863. – Part II Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXX-XLII-II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1899). Operations in Kentucky, Southwest Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Alabama, and North Georgia. August 11-October 19, 1863. – Part III Union Correspondence, etc. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXX-XLII-III. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Williams, Samuel Cole (1936). General John T. Wilder, Commander of the Lightning Brigade (PDF) (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 105. OCLC 903240789. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- Williams, Samuel Cole (1935). "General John T. Wilder" (PDF). Indiana Magazine of History. Indiana University Department of History. 31 (3): 169–203. ISSN 0019-6673. JSTOR 27786743. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- Woodworth, Steven E. (1998). Six Armies in Tennessee: The Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9813-2. OCLC 50844494.

- U.S. National Park Service. "NPS Hoover's Gap Battle Description". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. National Park Service. "Chickamauga Battle Description". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "History of Wilder's Brigade". www.oocities.org/wildersbrigade. Wilder's Brigade Mounted Infantry Living History Society. April 30, 2020.