The Liber selectarum cantionum (RISM A/I S 2804, RISM B/I 15204, VD16 S 5851, vdm 18) is a collection of motets which was printed in Augsburg in the workshop of Sigmund Grimm and Markus Wirsung in 1520. Its full title is Liber selectarum cantionum quas vulgo mutetas appellant sex quinque et quatuor vocum which means translated into English: "Book of selected songs, commonly called motets, for six, five, and four voices". The print is dedicated to the cardinal and prince-archbishop of Salzburg Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg. The epilogue was penned by the humanist Konrad Peutinger. Ludwig Senfl selected the compositions, prepared them for printing, and possibly also assisted as a proofreader.

Introduction

The Liber selectarum cantionum is the first motet anthology printed north of the Alps. It is subject of research by musicology, print studies, and art history mainly due to three extraordinary features:

- The impressive dimensions of 44.5 cm × 28.5 cm (c. 17.5″ × 11″) are an extreme exception for a print of mensural music in the 16th century.

- The types used for the notes are the biggest every produced for mensural music and seemingly were never used again.

- Some of the copies contain a full-page woodcut of a coat of arms employing seven colors including gold which is deemed one of the most elaborate of the entire 16th century.

These qualities were so innovative that they elevated the capabilities of the printing technology to a new level.[1]: 32

There are 20 extant copies of the Liber selectarum cantionum which is an exceedingly high number for a music print of this century. Additionally, there exists a fragment in the British Museum in London which consists of a single sheet of paper displaying the colored coat of arms on one page and the first half of the dedicatory letter on the other. It was bound into a print of Wiguleus Hund's Metropolis Salisburgensis that had been produced in Ingolstadt in the year 1582.[1]: 29

Social background

Several individuals were connected to the Liber selectarum cantionum and also among these people themselves connections have been established both directly and indirectly.

Since at least 1507 Grimm had been working in Augsburg as a physician and a pharmacist.[2] In the year 1513 he married Magdalena Welser.[3] This marriage had two important consequences. On the one hand, he advanced to the upper class since he gained access to the Herrenstube ("chamber of Lords") of Augsburg, the closed circle of the city's elite. On the other hand, a significant link arose because Magdalena Welser was a second cousin to Margarete Welser, the wife of Konrad Peutinger.[4] Therefore, Grimm and Peutinger were distantly related. Peutinger was one of the most reputable and influential figures of renaissance-humanism in Upper Germany. He participated in the city politics of Augsburg and supported emperor Maximilian I as a Kaiserlicher Rat ("imperial council"). He aided the family business of the Welsers by advising them in legal matters.[5]: 923 He was a keen proponent of book printing which he especially fostered in Augsburg.[6] By means of his advocacy several print projects of the Holy Roman Emperor were undertaken there.[7]

A crucial hub for the forging of new contacts was the Sodalitas litteraria Augustana which was founded in 1500 by Peutinger. This Augsburg-based society aimed at bringing together fellow humanists, exchanging ideas, and putting these into practice.[8] One of its members was Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg to whom the Liber selectarum cantionum was dedicated.[9] A number of printers from Augsburg also belonged to the association. Among those were Grimm and Wirsung.[10] It was probably due to both the family relationship as well as the Sodalitas which connected Peutinger to both of the printers that led him to write the epilogue for the music book.

Wirsung had been working as a pharmacist in Augsburg (similarly to Grimm) since 1496 but the principal source of his considerable income came from his main occupation as a long-distance merchant. Since at least 1502 he also engaged in bookselling.[11] In 1501 Wirsung married a second time. Like in his first marriage the bride, Agathe Sulzer, came from an affluent merchant family. As a result, Wirsung, too, was granted access to the Augsburg Herrenstube and he officially joined the local upper class.[5]: 933 One of the children born from this marriage was Christoph Wirsung.[12]

Grimm and Wirsung had been being friends for years when Grimm founded a print shop in 1517 which Wirsung joined in the same year as an equal partner.[13] In contrast to Grimm, the business was only a sideline activity for Wirsung. He could, however, provide the financial assets necessary for establishing and sustaining a printing office. The range of their prints was characterized by the highest standards and the attempts to produce innovative works. Both of these qualities apply to the Liber selectarum cantionum. For the woodcut of this print and others Grimm and Wirsung repeatedly hired an artist known by the Notname "Master of Petrarca" (German: Petrarcameister) from 1518 to 1522 whose identity has not yet been determined more precisely.[14]

Lang was a native from Augsburg and was born into an impoverished patrician family.[15] He was distantly related to Wirsung since the great-great-grandfather of his wife was simultaneously Lang's great-grandfather. Although Lang was a clergyman his actual legacy lies in his role as Maximilian's I "right hand" which made him the second-most powerful man in the empire.[16] He and Peutinger knew each other well, not only because of their memberships in the Sodalitas litteraria Augustana.[17] Physical evidence for this is for example the dedication of Peutinger's Sermones convivales from 1504 to Lang.

Only four days following the Liber selectarum cantionum Grimm and Wirsung published another work dedicated to Lang: La Celestina. This is a translation of an originally Spanish drama into German with the title Ain Hipsche Tragedia. The book was translated by Christoph Wirsung, Markus Wirsung's son, on the basis of an Italian version. In the dedicatory letter Christoph Wirsung reminds Lang multiple times of their family ties. Lang probably received the drama and the motet anthology at about or exactly the same time.

When Maximilian I passed away his will did not specify how his successor, Charles V, was to deal with the court staff. This also concerned the imperial court chapel (German: Hofkapelle) of which Ludwig Senfl was a member. Since Charles already had a chapel of his own at his disposal at his court in Spain, all of Maximilan's former singers feared losing their employment. It is not entirely clear where they resided in the wake of Maximilian's burial but it is presumed that a large number of them—including Senfl—left for Augsburg. It is likely that he began working at the Liber selectarum cantionum for Grimm and Wirsung during this time.

While Lang's status under Charles, too, was still unclear, Leonhard von Keutschach, prince-archbishop of Salzburg, died on June 7, 1519. Lang had been determined as his successor already in 1512. The riches of the archbishopric offered him the possibility to institute a courtly life that could approximate that of the emperor. On September 25, 1519, Lang was consecrated as a bishop and thereby became both the spiritual as well as the secular head of Salzburg.[18] Soon he founded a chapel which was meant to suffice the highest aspirations. To this end he attempted to move former musicians of Maximilian to his own court which in all likelihood included Senfl. The music in the Liber selectarum cantionum seems to have been chosen very deliberately as it is taken from the former imperial chapel. It was their level of professionalism that Lang sought to emulate.[19]

On October 28, 1520, the Liber selectarum cantionum was published, printed in the workshop of Grimm and Wirsung with a dedication to Lang, an epilogue by Peutinger and music, compiled and prepared for printing by Senfl.

Client

It is still unclear who initiated the project of the Liber selectarum cantionum. Related to this is the question what intentions were pursued by printing the book. There have, however, been posited a few theories trying to elucidate this subject.

According to the first theory emperor Maximilian I commissioned the book and it was merely his unexpected death that dragged the endeavor into a crisis. Instead of abandoning the project, Grimm and Wirsung adapted everything to Lang as a dedicatee. A re-dedication of this kind was neither unique nor questionable in the 16th century.

Maximilian's enthusiasm for the technology of printing speak in favor of this theory. In his plan of 130 future books that were to exalt him and the House of Hapsburg he also listed a music book.[20] One might also cite the seemingly unprofitable nature of the Liber selectarum cantionum which has been pointed out in reference to the imperial prints as well. If Grimm and Wirsung had been securely employed it would not have mattered to them if the book made a financial loss. Another feature shared with the imperial prints is the aesthetic since the book appears rather medieval even though the newest methods in printmaking were utilized. Furthermore, some of the imperial prints exist in two versions—one plainer and one more luxurious. In accordance with this differentiation, the Gebetbuch and the Theuerdank were printed on parchment and paper.[21] There is a similar traditional distinction of two versions of the Liber selectarum cantionum (see "Contents"). Finally, the colored woodcut can be used as an argument in favor of Maximilian as it is the only German woodcut of the 16th century which employs gold but is the only one not directly associated with the Hapsburgs.[1]: 32, 39

A different, yet more unlikely, possibility is that Senfl himself was the investor behind the book. A large amount of financial assets were necessary for a print of this magnitude which Senfl wouldn't have been able to raise. He would feature prominently in the paratexts (the foreword and the afterword) while he is mentioned rather briefly in actuality. In addition to this, he did not pursue employment in Salzburg but instead moved to Munich to serve at the court of William IV, Duke of Bavaria.[22]

There are two plausible ways in which Grimm and Wirsung might have initiated the printing project. The first resembles the theory mentioned above. After Maximilian I had died, they took matters into their own hands using their own funds. According to the other possibility they began printing the book in order to gain Lang's favor and/or to sell the copies in the conventional manner. One argument for this theory is La Celestina. Its dedication was meant to flatter Lang like the one found in the music book. It is definitely possible that they strove to become his "personal" printers at his new court. The proposition that the prints were meant to be sold is supported by entries in the copies of Jáchymov and Berlin. Within these, prices were recorded for the purchase (and binding) of the books. However, they do not prove that indeed all of the prints were sold. In regard to this theory it must also be noted that Grimm and Wirsung hardly could have expected to turn a profit with this kind of a book. The expenses for the production of the large note types were considerable. The choice of music, too, was inappropriate since it could have been performed only by highly professional singer ensembles whose demand was low because they could supply themselves with handwritten copies.

Another highly unlikely theory is that the Sodalitas litteraria Augustana was behind the print. Peutinger himself showed no interest at all in music.[23] Besides that, the aid of the Sodalitas usually was of an intellectual nature, not financial.[24] Moreover, they focused on ancient literature, not contemporary music.

As per the last theory Lang himself commissioned the print. According to this thesis the Liber selectarum cantionum was a prestige project. Its copies would have been gifted in gratitude to his loyal followers in order to demonstrate his power to them. This proposition, though, is contradicted by the entries of the owners of the books. None of them are verifiably linked to Lang.[25]

Contents

The following table offers an overview of the contents of the Liber selectarum cantionum:

- Title page

- Black-and-white coat of arms or index

- Index or colored coat of arms

- Two pages of the dedicatory letter including printing privileges

- Eight motets for six voices:

- Optime divino date munere pastor by Heinrich Isaac

- Praeter rerum seriem by Josquin Desprez

- Virgo prudentissima by Isaac

- O virgo prudentissima by Josquin

- Anima mea liquefacta est by Anonymous

- Benedicta es celorum regina by Josquin

- Pater de celis deus by Pierre de la Rue

- Sancte Pater divumque decus by Senfl

- Two separator pages

- Eight motets for five voices:

- Miserere mei deus by Josquin

- Inviolata integra by Josquin

- Salve crux arbor vitae by Jacob Obrecht

- Lectio actuum apostolorum by Anonymous (actually: Viardot)

- Stabat mater dolorosa by Josquin

- Missus est Gabriel angelus by Jean Mouton

- Anima mea liquefacta est by Anonymous

- Gaude Maria virgo by Senfl

- Two separator pages

- Eight motets for four voices:

- Ave sanctissima Maria by Isaac

- De profundis clamavi ad te by Josquin (actually: Nicolas Champion)

- Prophetarum maxime by Isaac

- Deus in adiutorium meum by Anonymous (actually: Nicolas Champion?)

- O Maria mater Christi by Isaac

- Discubuit Hiesus et discipuli by Senfl

- Usquequo domine by Senfl

- Beati omnes qui timent dominum by Senfl

- Epilogue addressed to the reader by Konrad Peutinger

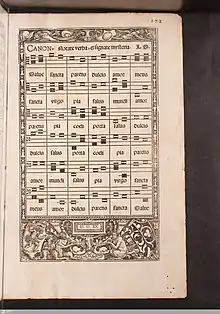

- Riddle canon Salve sancta parens by Senfl

Traditionally a distinction is made between a plainer and a more luxurious version of the print by taking a closer look at the first four pages exclusively. Their sequence is slightly different in each version. In the more valuable one it is: title page—index—(colored) woodcut—first page of the dedication. In the simpler version it is this instead: title page—(black-and-white) woodcut—index—first page of the dedication.

The first page states the title of the book while having the words arranged in a triangular shape. The only difference in the two versions pertains solely to the first letter which in the more luxurious copies is slightly larger than the rest of the letters.

.jpg.webp)

The woodcuts depict Lang's coat of arms with a quartered shield. The upper right and the lower left features Lang's personal coat of arms; the upper left and the lower right shows the coat of arms of the Salzburg archbishopric. It is surrounded by a cross signifying a papal legate and a red cardinal's hat which can be identified by the ten tassels hanging down at each side. In the simpler version only black has been used. In contrast, it is the colored woodcut which constitutes the luxuriousness of the more ostentatious copies. Matching several woodblocks on top of each other was a tremendously difficult feat. While six colors were printed in the usual way, the seventh color needed a different approach. Instead an adhesive was "printed" which served as a basis for gold leaf. Only in the late 19th century the complexity of this woodcut would be surpassed in the German-speaking lands.[1]: 24 The colored woodcut especially seems to have sparked considerable interest because it has been cut out of some of the copies.

There are two versions of the index as well. The headings differ slightly but the listing of the motets stays the same. The puzzle canon at the end of the book is omitted. While the simple version employs simple letters only, there are also ligatures (combinations of single letters), scribal abbreviations, and letters encircled in counters in the more luxurious version.

The dedicatory letter to Lang consists of two pages. Like before, two versions exist of the first page. In the plainer version the text following the salutation begins with a simple C-initial while the letter is enclosed by floral elements in the more luxurious version. Independently from the aforementioned traditionally distinguished two versions there are also two versions of the second page of the dedication. One of them explicitly identifies Senfl as Swiss. It is unclear if and why the printers removed or specifically added his place of origin. Also, this page marks the beginning of the foliation, i. e. every right page is numbered from here on forward.

In the dedication the printers Grimm and Wirsung address themselves to Lang. It is written in Latin at the highest stylistic level. Following the commendation of music they stress that only Lang deserves a work like the Liber selectarum cantionum. He may find pleasure in the book and show his benevolence towards them. Underneath the dedication the printing privileges of the pope and the emperor are disclosed: "Sub privilegio summi Pontificis et Caesaris". They protected Grimm and Wirsung from reprinters who would have been able to imitate and sell the Liber selectarum cantionum at a lower price by skipping the substantial effort of compiling the musical works and preparing them for printing.

24 motets follow suit. They are divided into three sections for six, five, and four voices, each containing eight motets. In the headline at the beginning of each work the name of the composer was added to whom Senfl ascribed the motet. It is most likely that part of Senfl's purview was the selection of the compositions. All of the motets were written only a few years prior and thus were relatively new. Half of them are explicitly addressed to the Virgin Mary or allow for a mariological interpretation which is owed to the widespread Marian devotion of the time. Josquin and Isaac were the most important influences on Senfl which is probably why they contributed the most motets to the book. As an expression of his reverence he positioned their compositions at the beginnings of the three segments. He placed his own works at the ends. This results in a slight contradiction as this both portrays him as humble as well as sets him up as the climax of this genre.[26]

On the second to last printed page Konrad Peutinger's Latin epilogue is reproduced serving as a kind of counterweight to the dedication. Peutinger's addressee is the reader of the book. He praises Grimm and Wirsung, Senfl, and the elaborateness of the print, especially the large note types. The letter is dated with the words "v. kal's Nove[m]bris. Anno salutis. M.D.XX." which translates to October 28, 1520.

At the end of the book a full-page black-and-white woodcut was printed. At the bottom the coats of arms of Grimm and Wirsung are displayed. The bulk of the page, however, is taken up by Senfl's riddle canon Salve sancta parens. Notes and syllables are entered into a grid of 6 × 6 squares. At the top an intentionally cryptic instruction in Latin was printed. Translated it reads: "Take note of the words and make the mystery apparent." There was entertainment to be found in having to try several ways of deciphering the message until the right solution was discovered. The canon may have been influenced by occultism of the renaissance. According to its teachings one could gain the favor of the sun with a grid of this size (and other activities) making them successful and invincible. It seems the intention was to wish Lang good fortune through magic.[27][28]

Printing process

The entire title page and the headlines of the index were printed with an Antiqua type set which was deemed inappropriate for liturgical prints.[29] There is no explicitly stated intention for the Liber selectarum cantionum to be used during mass but the motets are unambiguously of a religious nature. The aim of using the Antiqua typeface seems to have been to make the book appear more humanistic and scholarly. For the bulk of the print, however, a Rotunda script was employed which was especially popular in Augsburg and was thought to be noblest of all lettering styles.[30] Thus, its goal was to make the print seem more refined. In the index both type faces were combined which results in an elegant transition from one to the other.

For the motets Grimm and Wirsung utilized a process called double impression. First, the staffs alone were printed and only in the second step notes, clefs, the text, and other possibly needed elements followed suit. This type of technology was still relatively new at the time. The first print of mensural music using moveable types (named Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A) was created in 1501 in the workshop of Ottaviano Petrucci.

It is remarkably difficult to gauge what the print run amounted to since only few reliable figures are known for comparable projects. Furthermore, it is unknown how many printing presses Grimm and Wirsung possessed, how many workers they employed, and how long exactly the period was during which the Liber selectarum cantionum was printed. The print run may have been below 500 copies of which only a small part included the colored woodcut.[31]

In the 16th century several methods were available to deal with mistakes in the print. In the case of the Liber selectarum cantionum the workers started printing copies of one particular sheet which comprised four pages. While they continued with this task an expert took one of the finished sheets and examined it for flaws. If he noticed any mistakes the presses were stopped, the forme was corrected, and then the printing carried on again. This is aptly called a stop-press correction. The earlier and thus defective sheets were neither discarded nor corrected by hand. Instead they were incorporated into the books as they were. After the printing had finished the sheets were compiled quasi-randomly. Therefore, some copies of the Liber selectarum cantionum have earlier, erroneous sheets in one place and later, corrected ones at a different part of the book.

By comparing all extant copies it becomes clear that two styles of correction predominated. Folios 1–24 exhibit alterations on every page, the differences are numerous, and there are both substantial as well as purely aesthetic changes. Starting on folio 25 up until the end of the motets (folio 271r), there are pages which exist only in one version, there are far fewer alterations, and these modifications are substantial only. The motivation behind this change of style remains in the dark. It stands to reason that one proofreader—possibly Senfl himself—inspected the first pages and from folio 25 onward a different person took on the job.

If there are several versions of one single page, in most of the cases there are no more than two. In rarer instances three or even four versions exist. Several changes address obvious mistakes, e. g. typos of words or wrongly positioned custodes. Other variants cannot as easily be determined to be correct or wrong at a first glance. Yet by identifying clear errors and by comparing all copies one can also arrange these differences in temporal order. In this respect it is especially useful to keep the fact in mind that a sheet was always proofread as a whole. Thus, if there is an obvious mistake on one page, the variants on all other pages of the same sheet must be considered wrong as well.

The comparison of all copies reveals that there isn't just a more luxurious and a plainer version of the Liber selectarum cantionum. By not examining the first four pages exclusively but the entire book, one will find that no extant copy is identical any other. Based on the printing stage alone, every copy proves to be unique.

Later alterations

A multitude of changes were applied to the copies after the printing process in a strict sense.

One of the most obvious signs of later interference are the book covers because no two of them are alike. Many of them date back to the first owners. This allows for the deduction that the Liber selectarum cantionum was handed over in an unbound state as it was common among book merchants in the 16th century.[32] In most cases books were bound close to the owner's residence. By doing so it was commonplace to place an empty sheet of paper before and after the printed part. These sheets are called endpapers. In many copies owners have entered their names on the front endpaper (occasionally also at the end or on the printed pages). In most cases these people are historically identifiable and can be ranked among the social elite. Yet they were not wealthy or influential enough to have a chapel of their own. This shows that the motivation to purchase a copy was not to supply a singer ensemble with music. Rather it was the extraordinary features of the printed that were mentioned at the beginning that attracted them. This hypothesis is supported by the large array of print corrections since Grimm and Wirsung neither corrected the erroneous pages nor did they add an errata list at the end of the book. This suggests that practicality was only of secondary importance to both them and the buyers. The names do not stand in any relation to Lang which argues against the theory that he may have commissioned the print. A few of the named people even were actively promoting Protestantism. Lang surely would not have given them this book as a gift.

By looking at other inscriptions and stamps one can detect a trend concerning the history of owners (provenance). A man of the upper class bought a copy which remained for some time in the family until someone gifted it to a clerical institution. During the course of secularization its possessions were handed over to the state and thereby the copy was given to a public library. In recent times some of these have digitized their copy and made it publicly available on the internet.

While most of the entries by the owners are rather succinct there are two notable exceptions. In the Regensburg copy two pages of a handwritten foreword were added. It is a dedication by Stephan Consul addressing the Regensburg senate in 1560. He was working on a translation of the New Testament with Primus Truber. If the senators were willing to continue to support him they would share God's reward with him. Similarly, two handwritten pages of a dedication were supplemented in the copy of Jáchymov. In Latin poems Matthias Gucchianus gifts the book to Dr. Wolfgang Gortelerus whose musical skills are lauded.

In two copies scribes wrote down notes of their prices. The Berlin copy records a price of two and a half guilder for the purchase of the book and three quarters of a guilder for its binding. The Jáchymov copy documents an expense of two guilder for buying the book. This proves that a part of the copies—possibly all of them—were up for sale.[33]

In the motet section most errors were left uncorrected. But there are some entries suggesting that the copies were actually used in a practical sense. In some of the motets numbers were added next to ligatures (combination of notes) denoting their values. Occasionally there are handwritten corrections of the notes or the text. These do not necessarily match the later/corrected versions printed in the workshop of Grimm and Wirsung. Alterations of this sort might be called selective while there are only few interventions on a larger scale. In the Tübingen copy a scribe added an optional voice to Josquin's Miserere mei deus. Because of the new conception regarding the Virgin Mary in Protestantism someone adapted texts in the copies of Fulda and Cambridge (Massachusetts) so that Mary is not worshipped directly any longer.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Giselbrecht, Elisabeth; Upper, Elizabeth (2012). Gasch, Stefan; Tröster, Sonja; Lodes, Birgit (eds.). Glittering Woodcuts and Moveable Music. Decoding the Elaborate Printing Techniques, Purpose, and Patronage of the Liber Selectarum Cantionum. Wiener Forum für ältere Musikgeschichte. Tutzing: Hans Schneider Verlag. ISBN 978-3862960323.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Reske, Christoph (2007). Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet. Auf der Grundlage des gleichnamigen Werkes von Josef Benzing. Beiträge zum Buch- und Bibliothekswesen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 33.

- ↑ Künast, Hans-Jörg (1997). "Getruckt zu Augspurg". Buchdruck und Buchhandel in Augsburg zwischen 1468 und 1555. Studia Augustana. Augsburger Forschungen zur europäischen Kulturgeschichte. Tübingen: Niemeyer Verlag. pp. 43, footnote 45. ISBN 978-3-484-16508-3.

- ↑ Geffcken, Peter (2002). Häberlein, Mark; Burkhardt, Johannes (eds.). Die Welser und ihr Handel 1246-1496. Colloquia Augustana. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. p. 164. ISBN 978-3-05-003412-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 Geffcken, Peter (1998). Grünsteudel, Günther (ed.). Welser (2nd ed.). Augsburg: Perlach-Verlag. ISBN 3-922769-28-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Künast, Hans-Jörg (1997). "Getruckt zu Augspurg". Buchdruck und Buchhandel in Augsburg zwischen 1468 und 1555. Studia Augustana. Augsburger Forschungen zur europäischen Kulturgeschichte. Tübingen: Niemeyer Verlag. p. 99. ISBN 978-3-484-16508-3.

- ↑ Bellot, Josef (1967). "Conrad Peutinger und die literarisch-künstlerischen Publikationen Kaiser Maximilians". Philobiblon. 11: 171–189.

- ↑ Hägele, Günter (1998). Grünsteudel, Günther (ed.). Sodalitas Litteraria Augustana (2 ed.). Augsburg: Perlach-Verlag. p. 821. ISBN 3-922769-28-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Bator, Angelika (2004). "Der Chorbuchdruck Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520). Ein drucktechnischer Vergleich der Exemplare aus Augsburg, München und Stuttgart". Musik in Bayern. Halbjahresschrift der Gesellschaft für Bayerische Musikgeschichte e.V. 67: 13.

- ↑ Hägele, Günter (1998). Grünsteudel, Günther (ed.). Sodalitas Litteraria Augustana (2 ed.). Augsburg: Perlach-Verlag. p. 822. ISBN 3-922769-28-4.

- ↑ Gustavson, Royston (2002). Finscher, Ludwig (ed.). Grimm & Wirsung. Vol. 8 (2 ed.). Kassel: Bärenreiter-Verlag. p. 43.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Reinhard, Wolfgang, ed. (1996). Augsburger Eliten des 16. Jahrhunderts. Prosopographie wirtschaftlicher und politischer Führungsgruppen 1500–1620. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. p. 974. ISBN 3-05-002861-0.

- ↑ Gustavson, Royston (2002). Finscher, Ludwig (ed.). Grimm & Wirsung. Vol. 8. Kassel: Bärenreiter-Verlag. p. 43.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Ott, Norbert (1997). Gier, Helmut; Janota, Johannes (eds.). Frühe Augsburger Buchillustration. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-3-447-03624-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Hintermaier, Ernst (1993). Hintermaier, Ernst (ed.). Erzbischof Matthäus Lang – Ein Mäzen der Musik im Dienste Kaiser Maximilians I. Musiker und Musikpflege am Salzburger Fürstenhof von 1519 bis 1540. Salzburg: Selke Verlag. p. 29. ISBN 978-3-901353-00-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Friedhuber, Inge (1973). Novotny, Alexander; Pickl, Othmar (eds.). Kaiser Maximilian I. und die Bemühungen Matthäus Langs um das Erzbistum Salzburg. Graz: Historisches Institut der Universität Graz. p. 123.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Eder OSB, Petrus (1993). Hintermaier, Ernst (ed.). Die Gebildeten im Salzburg der beginnenden Reformation. Salzburg: Selke Verlag. pp. 234, fn. 77. ISBN 978-3-901353-00-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Sallaberger, Johann (1997). Kardinal Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg (1468–1540). Staatsmann und Kirchenfürst im Zeitalter von Renaissance, Reformation und Bauernkriegen. Salzburg: Verlag Anton Pustet. pp. 17, 87, 207. ISBN 978-3-7025-0353-6.

- ↑ Birkendorf, Rainer (1994). Der Codex Pernner. Quellenkundliche Studien zu einer Musikhandschrift des frühen 16. Jahrhunderts (Regensburg, Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek, Sammlung Proske, Ms. C 120). Collectanea musicologica. Vol. 1. Augsburg: Wißner. p. 172. ISBN 978-3-928898-27-0.

- ↑ Senn, Walter (1969). Maximilian und die Musik. Innsbruck: Land Tirol, Kulturreferat, Landhaus. p. 73. ISBN 3-902112-03-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Schmitz, Wolfgang (1998). Besch, Werner (ed.). Gegebenheiten deutschsprachiger Textüberlieferung vom Ausgang des Mittelalters bis zum 17. Jahrhundert. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft. Vol. 1 (2 ed.). Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 321. ISBN 978-3-11-011257-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Lodes, Birgit (2002). Finscher, Ludwig (ed.). Senfl. Vol. 15 (2 ed.). Kassel: Bärenreiter-Verlag. p. 571.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Künast, Hans-Jörg (2010). Lodes, Birgit (ed.). Buchdruck und -handel des 16. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachraum. Mit Anmerkungen zum Notendruck und Musikalienhandel. Wiener Forum für Ältere Musikgeschichte. Tutzing: Hans Schneider Verlag. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-3-86296-004-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Künast, Hans-Jörg (1997). "Getruckt zu Augspurg". Buchdruck und Buchhandel in Augsburg zwischen 1468 und 1555. Studia Augustana. Augsburger Forschungen zur europäischen Kulturgeschichte. Tübingen: Niemeyer Verlag. p. 71. ISBN 978-3-484-16508-3.

- ↑ Schiefelbein, Torge (2022). Same Same but Different. Die erhaltenen Exemplare des Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520). Wiener Forum für ältere Musikgeschichte (in German). Vienna, Austria: Hollitzer Verlag. p. 94. ISBN 978-3-99012-992-0.

- ↑ Schiefelbein, Torge (2022). Same Same but Different. Die erhaltenen Exemplare des Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520). Wiener Forum für ältere Musikgeschichte (in German). Vienna, Austria: Hollitzer Verlag. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-3-99012-992-0.

- ↑ Haberl, Dieter (2004). "'CANON. Notate verba, et signate mysteria' – Ludwig Senfls Rätselkanon Salve sancta parens, Augsburg 1520. Tradition – Auflösung – Deutung". Neues Musikwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch. 12.

- ↑ Lindmayr-Brandl, Andrea (2010). Laubhold, Lars E.; Walterskirchen, Gerhard (eds.). Ein Rätselkanon für den Salzburger Erzbischof Matthäus Lang: Ludwig Senfls 'Salve sancta parens'. Veröffentlichungen zur Salzburger Musikgeschichte. Munich: Strube Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89912-140-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Reske, Christoph (2003). Arnold, Klaus; Fuchs, Franz; Füssel, Stephan (eds.). Erhard Ratdolts Wirken in Venedig und Augsburg. Pirckheimer Jahrbuch für Renaissance- und Humanismusforschung. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 30. ISBN 978-3-447-09345-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Janota, Johannes (1997). Gier, Helmut; Janota, Johannes (eds.). Von der Handschrift zum Druck. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 136. ISBN 978-3-447-03624-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Schiefelbein, Torge (2022). Same Same but Different. Die erhaltenen Exemplare des Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520). Wiener Forum für ältere Musikgeschichte (in German). Vienna, Austria: Hollitzer Verlag. p. 185. ISBN 978-3-99012-992-0.

- ↑ Werfel, Silvia (1997). Gier, Helmut; Janota, Johannes (eds.). Einrichtung und Betrieb einer Druckerei in der Handpressenzeit (1460 bis 1820). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 97. ISBN 978-3-447-03624-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Schiefelbein, Torge (2022). Same Same but Different. Die erhaltenen Exemplare des Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520). Wiener Forum für ältere Musikgeschichte (in German). Vienna, Austria: Hollitzer Verlag. pp. 262, 285, 351. ISBN 978-3-99012-992-0.

Further reading

In English

- Creighton Roberts, Kenneth (1965). The Music of Ludwig Senfl: A Critical Appraisal. With Vol II: Appendix D. The Liber Selectarum Cantionum of 1520 (A Complete Transcription). Dissertation University of Michigan.

- Giselbrecht, Elisabeth; Upper, Elizabeth (2012). Gasch, Stefan; Tröster, Sonja; Lodes, Birgit (eds.). Glittering Woodcuts and Moveable Music. Decoding the Elaborate Printing Techniques, Purpose, and Patronage of the Liber Selectarum Cantionum. Senfl-Studien I. Wiener Forum für ältere Musikgeschichte. Tutzing: Hans Schneider Verlag. ISBN 978-3862960323.

- Schlagel, Stephanie P. (2002). "The Liber selectarum cantionum and the 'German Josquin Renaissance'". The Journal of Musicology 19.

- Picker, Martin (1998). Staehelin, Martin (ed.). Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg: Grimm & Wirsung, 1520). A Neglected Monument of Renaissance Music and Music Printing. Gestalt und Entstehung musikalischer Quellen im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Wolfenbütteler Forschungen; Quellenstudien zur Musik der Renaissance. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447041188.

- Gasch, Stefan; Tröster, Sonja; Lodes, Birgit, eds. (2019). RISM 15204. Ludwig Senfl (c.1490–1543). A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works and Sources. 2. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers 2019. p. 156–157. ISBN 978-2503584799.

- Lindmayr-Brandl, Andrea (2010). "Magic Music in a Magic Square. Politics and Occultism in Ludwig Senfl's Riddle Canon Salve sancta parens". Tijdschrift van de koninklijke vereniging voor nederlandse muziekgeschiedenis LX-1.

In German

- Bator, Angelika (2004). "Der Chorbuchdruck Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520). Ein drucktechnischer Vergleich der Exemplare aus Augsburg, München und Stuttgart" [The choir book print Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520). A print-based comparison of the copies in Augsburg, Munich, and Stuttgart]. Musik in Bayern. Halbjahresschrift der Gesellschaft für Bayerische Musikgeschichte e.V. 67.

- Haberl, Dieter (2004). "'CANON. Notate verba, et signate mysteria' – Ludwig Senfls Rätselkanon Salve sancta parens, Augsburg 1520. Tradition – Auflösung – Deutung" ['CANON. Notate verba, et signate mysteria' – Ludwig Senfl's riddle canon Salve sancta parens, Augsburg 1520. Tradition – solution – interpretation]. In: Neues Musikwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch. Nr. 12, 2004, S. 9–52.

- Hintermaier, Ernst; Lindmayr, Andrea (1993); Hintermaier, Ernst (ed.). LIBER SELECTARVM CANTIONVM QVAS VVLGO MVTETAS APPELLANT SEX QVINQVE ET QVATVOR VOCVM. Salzburg zur Zeit des Paracelsus. Musiker, Gelehrte, Kirchenfürsten. Katalog zur 2. Sonderausstellung der Johann-Michael-Haydn-Gesellschaft in Zusammenarbeit mit der Erzabtei St. Peter "Musik in Salzburg zur Zeit des Paracelsus". Salzburg: Selke Verlag. ISBN 978-3901353000.

- Redeker, Raimund (1995). Lateinische Widmungsvorreden zu Meß- und Motettendrucken der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts [Latin dedicatory prologues in mass and motet prints in the first half of the 16th century]. Schriften zur Musikwissenschaft aus Münster. Eisenach: Verlag der Musikalienhandlung Karl Dietrich Wagner. p. 73–85. ISBN 978-3889790668.

- Schiefelbein, Torge (2022). Same Same but Different. Die erhaltenen Exemplare des Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520) [Same Same but Different. The extant copies of the Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520)]. Wiener Forum für ältere Musikgeschichte. Vienna, Austria: Hollitzer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-99012-992-0 (earlier online version).

External links

Digitized copies

- Copy of the der Austrian National Library in Vienna, Austria

- Copy of the Exposition of the Library of the Latin School in Jáchymov, Czech Republic (in Czech)

- Copy of the Bavarian State Library in Munich, Germany

- Copy of the State Library Regensburg, Germany

- Copy of the State Library of Württemberg, Germany (in German)

- One of the two copies of the British Library in London, UK

- Fragment of the British Museum in London, UK