Leopold Forstner (2 November 1878 in Bad Leonfelden, Upper Austria – 5 November 1936 in Stockerau[1][2]) was an artist who was part of the Viennese Secession movement, working in the Jugendstil style, focusing particularly on the mosaic as a form.[3][4][5]

Biography

Forstner was the only son of Franz Forstner, a carpenter, and his wife Anna. He completed his primary education in Leonfelden, before completing his education in Linz. Through his uncle Anton Forstner he was able to be released from an apprenticeship in glass painting and mosaic installation in Innsbruck and instead studied at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna.[6] There, he studied under Karl Karger and Koloman Moser.[7] Moser would go on to mentor Forstner. After the end of his studies in Vienna, Forstner would go on to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, under Ludwig von Herterich.

Although his studies in Munich ran from 1902 to 1903, Forstner had begun to work as an artist, painter and illustrator from 1901. In 1906 he founded the "Wiener Mosaikwerkstätte", and two years later he was given a trade licence to produce glass mosaics.[8] He presented work at the 1908 Wiener Kunstschau, organised by Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffman.[9] He also presented work at the Spring showings of the Hagenbund, a Viennese art collective.

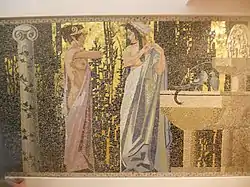

Originally Forstner's mosaics were in the traditional Venetian or Florentine technique and style, he became famous for his mixed media and tile mosaics, for example the Klimt frieze in the Palais Stoclet.[10][11][12] As well as his own designs, Forstner collaborated with many important artists of the time, for example Klimt, Otto Wagner, Otto Schönthal and Emil Hoppe.

Between 1908 and the outbreak of the First World War he produced his most successful work, and expanded his workshop. In 1911, he married his wife, Stephanie (née Stöger), and together they had two children, Georg (born 1912) and Karl (born 1913).

In 1912 he became a member of the Bund Österreichischer Künstler, and with the architect Cesar Poppovits and the painter Alfred Basel, he founded the Wiener Friedhofskunst. That year, the success and popularity of his work enabled him to build his own glass kiln. In 1913 he became an associate member of the Society of Austrian Architects.

During the First World War, he was a Collection Officer in Albania and Macedonia.[13] After the war, he moved to Stockerau, the home town of his wife. There he established two new premises but was forced to sell both.

Due to the poor economic conditions in Austria after the First World War, Forstner worked more as an all-round artist rather than focusing solely on mosaics. He worked on several War Memorials, as an architect and landscape designer and, from 1929 to 1936 as the art master at Hollabrunn Gymnasium. A road in Hollabrunn is named for him.[2]

Major works

- Glass window for the Austrian Postal Savings Bank Building (1904–1906)

- Memorial for Mozart at the Mozart House, Linz (1906)

- Venetian-style mosaic of St George and St Hubert, shown at the 1908 Wiener Kunstschau.

- Apse mosaic in parish church of Ebelsberg (near Linz), which features a relief by Wilhelm Bormann (1908).[4]

- Mosaic of "Spring" in the Grand Hotel Wiesler in Graz.[14]

- Mosaic of the coat of arms of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy for the 1910 Wiener Jagdaustellung, together with Györgyfaloy.

- Windows and wall mosaics of the side chapel and a representation of the Four Evangelists in the dome of the Karl-Borromäus-Kirche in the Zentralfriedhof (1911).[15]

- Mosaic friezes at Stoclet Palace, working to Klimt's designs (1909–1911)[12]

- Windows (to the design of Koloman Moser) and high altar mosaic (to the designs of Carl Ederer, Remigius Geyling and Rudolf Jettmar) for the Kirche am Steinhof (1906–1912)[11][16]

- Mosaics in the entrance hall of the Dianabades (1914).

- Mosaic of St. George for the church tower of Stockerau, 1914–1916. (The mosaic was removed in 1937 but restored in 1989. It now resides in chapel of Stockerau Hospital.)

- Dragoon war memorial, Stockerau (1926)

- New design for the city park of Stockerau (1928)

- Memorial for the fallen of the First World War, Stockerau Gymnasium (1930)

- Glassmaker for the St. Gertrude Window in the parish church of Währing.

References

- ↑ "Neues "Kulturviertel" am Leonfeldner Stadtplatz". www.nachrichten.at. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- 1 2 Fürnkranz, Herbert (7 October 1989). "Street Names in Hollabrunn" (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ Borchhardt-Birbaumer, Brigitte. "Viel besser als Bassena – Wiener Zeitung Online". Kunst - Wiener Zeitung Online. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- 1 2 "Ein Kenner des Jugendstils zeigt die Schätze der Stadt aus der Epoche". www.nachrichten.at. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ↑ Mrazek, Wilhelm (1981). "Leopold Forstner": ein Maler und Material-Künstler des Wiener Jugendstils. Belvedere. ISBN 9783900175221.

- ↑ Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, Volumes 29-33. 1985.

- ↑ Baroni, Daniele; Moser, Kolo; D'Auria, Antonio (1986). Kolo Moser: Graphic Artist and Designer. Rizzoli. p. 44. ISBN 9780847806676.

- ↑ Murr, Beate (2014). ""I knew right from the start that the whole thing would be damned expensive" – Gustav Klimt's Cartoons for the Stoclet Frieze: Their Creation, Execution, and Conservation, Part II". Restaurator. International Journal for the Preservation of Library and Archival Material. 35 (1). doi:10.1515/res-2014-0003. S2CID 96570529.

- ↑ "Vienna gallery recreates 1908 Austrian art exhibit – USATODAY.com". usatoday30.usatoday.com. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ↑ "Palais Stoclet ist Weltkulturerbe". www.oe24.at. 2009-06-27. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- 1 2 Beller, Steven (2006). A Concise History of Austria. Cambridge University Press. pp. 173. ISBN 9780521478861.

- 1 2 Rogoyska, Jane; Bade, Patrick (2012). Best of Gustav Klimt. Parkstone International. p. 127. ISBN 9781780427294.

- ↑ Nachrichten, Salzburger (11 April 2016). "Schloss Artstetten stellt Künstler Leopold Forstner vor". www.salzburg.com. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ↑ "The Graz is greener in Austria | The National". www.thenational.ae. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ↑ Hollein, Hans; Cooke, Catherine (1986). Vienna dream and reality: a celebration of the Hollein installations for the exhibition 'Traum und Wirklichkeit Wien 1870–1930' in the Künstlerhaus Vienna, Volume 55. AD Editions. p. 8.

- ↑ Schwab, Liselotte (2010). Hommage an eine ermordete Kaiserin: die Elisabeth-Kapelle in der Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Jubil"umskirche in Wien II., Mexikoplatz. Diplomica Verlag. ISBN 9783836690157.