| |||

| Identifiers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI |

| ||

| ChEMBL | |||

| DrugBank | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

The latrunculins are a family of natural products and toxins produced by certain sponges, including genus Latrunculia and Negombata, whence the name is derived. It binds actin monomers near the nucleotide binding cleft with 1:1 stoichiometry and prevents them from polymerizing. Administered in vivo, this effect results in disruption of the actin filaments of the cytoskeleton, and allows visualization of the corresponding changes made to the cellular processes. This property is similar to that of cytochalasin, but has a narrow effective concentration range.[1] Latrunculin has been used to great effect in the discovery of cadherin distribution regulation and has potential medical applications.[2] Latrunculin A, a type of the toxin, was found to be able to make reversible morphological changes to mammalian cells by disrupting the actin network.[3]

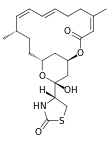

Latrunculin A:

| Molecular Formula: | C22H31NO5S[4] |

|---|---|

| Molecular Weight: | 421.552 g/mol[4] |

Target and functions

Gelsolin - Latrunculin A causes end- blocking; this protein binds to the barbed sides of the actin filaments which accelerates nucleation. This calcium-regulated protein also plays a role in assembly and disassembly of cilia[4] which plays a crucial role in handedness.

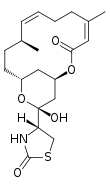

Latrunculin B:

| Molecular Formula: | C20H29NO5S[5] |

| Molecular Weight: | 395.514 g/mol |

Target and Function

Actin- Latrunculin B makes up the structure of the actin fibers.

Protein spire homolog 2- needed for cell division, vesicle transport within the actin filament and is essential for the formation of the cleavage formation during cell division.[6]

History

Latrunculin is a toxin that is produced by sponges. The red-coloured Latrunculia magnifica Keller is an abundant sponge in the gulf of Eilat and the gulf of Suez[7] in the red sea, where it lives at a depth of 6–30 meters.[8] The toxin was discovered around 1970. Researchers observed that the red-coloured sponges, Latrunculia magnifica Keller, were never damaged or eaten by fishes, while others were. Furthermore, when researchers squeezed the sponges in the sea, they observed that a red fluid came out. Fishes nearby immediately fled the surrounding area when the sponge secreted the fluid. These were the first indications that these sponges produced a toxin. Later this hypothesis was confirmed by squeezing the sponge in an aquarium with fish, whereupon the fish showed a loss of balance and severe bleeding, dying within only 4–6 minutes.[8] Similar effects were observed when the toxin was injected in mice.

Latrunculin makes up to 0.35% of the dry weight of the sponge.[7] There are two main forms of the toxin, A and B. Latrunculin A is only present in sponges which live in the gulf of Suez while latrunculin B only exist in sponges in the gulf of Eilat. Why this is the case is still under investigation.[7]

Structure

There are several isomers of latrunculin, A, B, C, D, G, H, M, S and T. The most common structures are latrunculin A and B. Their formulas are respectively C22H31NO5S and C20H29NO5S. The macrolactone ring on top that contains double bonds is a structural feature of the latrunculin molecules. The side chain contains an acylthiazolidinone substitute. Besides these natural occurring forms, scientist have made synthetic forms with different toxic strengths. Figure 2 shows some of these forms with their relative ability to disrupt microfilament activity. Semisynthetic forms that contained N-alkylated derivates were inactive.[9]

Mechanism of action

Latrunculin A and latrunculin B affect polymerization of actin. Latrunculin binds actin monomers near the nucleotide binding cleft with 1:1 stoichiometry and prevents them from polymerizing.[1] The nucleotide monomers are prevented from dissociation from the nucleotide binding cleft, thus preventing polymerizing.[10]

Experimental evidence shows that latruculin-A is biologically active in the solvent DMSO, but not in aqueous solutions, as demonstrated in cell culture and in brain tissue[11] probably due to cellular permeation.

When actin is impaired due to latrunculin, Shiga toxins have a better chance of infiltrating the intestinal epithelial monolayer in E. coli, which may cause a higher chance of generating gastrointestinal illnesses.[12]

It seems that actin monomers are more sensitive to bind latrunculin A than to bind Latrunculin B.[13] In other words, latrunculin A is a more potent toxin. Latrunculin B is inactivated faster than latrunculin A.[14]

The prevention of polymerizing of the actin filaments causes reversible changes in the morphology of mammalian cells.[15] Lantranculin interferes with the structure of the cytoskeleton in rats.[16]

After latrunculin B exposure, mouse fibroblasts grow bigger and PtK2 kidney cells from a potoroo stem produced long, branched extensions.[17] The extensions seem to be an accumulation of actin monomers.

Metabolism

Yeast cells in absence of the proteins osh3 or osh5 demonstrated hypersensitivity to latrunculin B.[18] The osh proteins are homologous to OSBP generated enzymes that appear in mammals, indicating that these might play a role in the toxicokinetics of latrunculins.

Yeast mutants that are resistant to latrunculin show a mutation, D157E, that initiates a hydrogen bond with latrunculin.[10] Other yeast mutants adjust the binding site, thus making it resistant to latrunculin.

No research has been done to figure out how the biotransformation of latrunculin works in eukaryotic cells. However, research suggests that it is the unaltered form of latrunculin that causes toxic effects.[3]

Toxicity

As latrunculin inhibits actin polymerization and actomyosin contractile ability, exposure to latrunculin may result in cellular relaxation, expansion of drainage tissues and decreased outflow resistance in e.g. the trabecular meshwork.

Plant

Latrunculin B causes marked and dose-dependent reductions in pollen germination frequency and pollen tube growth rate.[19]

Adding latrunculin B to solutions of pollen F-actin produced a rapid decrease in the total amount of polymer, the extent of depolymerization increasing with the concentrations of the toxic. The concentration of latrunculin B required for half-maximal inhibition of pollen germination is 40 to 50 nM, whereas pollen tube extension is much more sensitive, requiring only 5 to 7 nM LATB for half-maximal inhibition. The disruption of germination and pollen tube growth by latrunculin B is partially reversible at low concentrations. (<30 nM).[19]

Animal

Squeezing Latrunculia magnifica into aquarium with fishes causes their almost immediate agitation, followed by hemorrhage, loss of balance and death in 4–6 minutes.[20]

Latrunculin A has been used as acrosome reaction inhibitor of guinea pig in laboratory conditions.[21]

Human

Lat-A-induces reduction of actomyosin contractility. This is associated with trabecular meshwork porous expansion without evidence of reduced structural extracellular matrix protein expression or cellular viability.[22] In high doses, latrunculin can induce acute cell injury and programmed cell death through activating the caspase-3/7 pathway.[20]

Lethal doses

TDLO - Lowest Published Toxic Dose

LD50 – median Lethal Dose[23]

| Indicator | Species | Dose |

| Oral TDLO | Man | 1,14 ml/kg, 650 mg/kg |

| Oral LD50 | Rat | 7,06 mg/kg |

| Oral LD50 | Mouse | 3,45 g/kg, 10,5 ml/kg |

| Oral LD50 | Rabbit | 6,30 mg/kg |

| Inhalation LC50 | Rat | 6h: 5,900 mg/m3

10h: 20,000 ppm |

| Inhalation LCLO | Mouse | 7h: 29,300 ppm |

| Inhalation TCLO | Human | 20m: 2,500 mg/m3

30m: 1,800 ppm |

| Irritation eyes | Rabbit | 24h: 500 mg |

| Irritation skin | Rabbit | 24h: 20 mg |

Applications

In nature, latrunculins are used by the sponges themselves as a defense mechanism, and for the same purpose are also sequestered by certain nudibranchs.[24]

Latrunculins are produced for fundamental research and have potential medical applications as latrunculins and their derivatives show antiangionic, antiproliferative, antimicrobial and antimetastatic activities.[2]

Defense mechanism

Like many other sessile organisms, sponges are rich of secondary metabolites with toxic properties and most of them, including Latrunculin, have a defense role against predators, competitors and epibionts.[25]

The sponges themselves are not damaged by latrunculin. As a measure against self-toxination, they keep the latrunculin in membrane-bound vacuoles, that also function as secretory and storage vesicles. These vacuoles are free of actin and prevent the latrunculin from entering the cytosol where it would damage actin.[25] After production in the choanocytes, the latrunculin is transferred via the archeocytes to the vulnerable areas of the sponges where defense is needed, such as injured or regenerating sites.[25]

Sequestering by nudibranchs

Sea slugs of the genus Chromodoris sequester different toxics from the sponges that they eat as defensive metabolites, including latrunculin. They selectively transfer and store latrunculin in the sites of the mantle that are most exposed to potential predators.[24] It is thought that the digestive system of the nudibranchs plays an important role in the detoxification.[24]

In 2015, the discovery that five closely related sea slugs of the genus Chromodoris all use latrunculin as defense, indicates that the toxic might be used via Müllerian mimicry.[24]

Research

Latrunculins are used for fundamental research like cytoskeleton studies. Many functions of actin have been determined by using latrunculins to block actin polymerization followed by examining the effects on the cell. Using this method, the importance of actin for the polarized localization of proteins, polarized exocytosis and the maintenance of cell polarity have been shown.[26]

In the field of Neuroscience, latrunculin has been used to demonstrate the role of actin in regulating voltage-gated ion channels in different nerve cells,[27] showing that latrunculin treatment can alter the electrical activity of nerve cells.[27][28] Latrunculin shows a dose-dependent inhibition of K+ currents and acute application can induce the firing of multiple action potentials , which could underlie a mechanism of defense via nociceptors.[28] In addition, latrunculin-A was used to demonstrate the role of dentritic spine neck shrinkage for the induction of synaptic plasticity.[11]

Medical applications

Latrunculin A and B and derivatives have potential as novel chemotherapeutic agents.[2][29] The potential use of latrunculin as growth inhibitors of tumor cells has already been investigated for certain forms of gastric cancer,[20] metastatic breast cancer[29] and prostate tumors.[30] In lower doses, latrunculin can be used to decrease disaggregation and cell migration, thereby preventing invasive activities of tumor cells.[30] In higher doses, latrunculin can induce acute cell injury and programmed cell death through activating the caspase-3/7 pathway, and thus be used to kill tumor cells.[20] Latrunculin A and its 17-O-[N-(benzyl)carbamate ( suppress hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation in T47D breast tumor cells.[30]

Latrunculin also is a potential therapeutic for ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Latrunculin A and B are shown to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton of the trabecular meshwork that is important for regulating humor outflow resistance and thereby intraocular pressure.[31][32] By cellular relaxation and loosened cell-cell junctions, latrunculin can increase humor outflow facility. The first human trial of lantruculin B as treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma showed significantly lower intraocular pressure in patients.[32]

References

- 1 2 Braet F, De Zanger R, Jans D, Spector I, Wisse E (September 1996). "Microfilament-disrupting agent latrunculin A induces and increased number of fenestrae in rat liver sinusoidal endothelial cells: comparison with cytochalasin B". Hepatology. 24 (3): 627–35. doi:10.1002/hep.510240327. PMID 8781335. S2CID 30443511.

- 1 2 3 El Sayed KA, Youssef DT, Marchetti D (February 2006). "Bioactive natural and semisynthetic latrunculins". Journal of Natural Products. 69 (2): 219–23. doi:10.1021/np050372r. PMID 16499319.

- 1 2 Coué M, Brenner SL, Spector I, Korn ED (March 1987). "Inhibition of actin polymerization by latrunculin A". FEBS Letters. 213 (2): 316–8. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(87)81513-2. PMID 3556584.

- 1 2 3 Pubchem. "Latrunculin A". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ Pubchem. "Latrunculin A". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ Pubchem. "Latrunculin A". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- 1 2 3 Groweiss A, Shmueli U, Kashman Y (1983-10-01). "Marine toxins of Latrunculia magnifica". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 48 (20): 3512–3516. doi:10.1021/jo00168a028.

- 1 2 Kashman V, Groweiss A, Shmueli U (January 1980). "Latrunculin, a new 2-thiazolidinone macrolide from the marine sponge". Tetrahedron Letters. 21 (37): 3629–3632. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(80)80255-3.

- ↑ Maier ME (May 2015). "Design and synthesis of analogues of natural products". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 13 (19): 5302–43. doi:10.1039/C5OB00169B. PMID 25829247.

- 1 2 Morton WM, Ayscough KR, McLaughlin PJ (June 2000). "Latrunculin alters the actin-monomer subunit interface to prevent polymerization". Nature Cell Biology. 2 (6): 376–8. doi:10.1038/35014075. hdl:1842/757. PMID 10854330. S2CID 1803612.

- 1 2 Tazerart S, Mitchell DE, Miranda-Rottmann S, Araya R (August 2020). "A spike-timing-dependent plasticity rule for dendritic spines". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4276. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4276T. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17861-7. PMC 7449969. PMID 32848151.

- ↑ Maluykova I, Gutsal O, Laiko M, Kane A, Donowitz M, Kovbasnjuk O (June 2008). "Latrunculin B facilitates Shiga toxin 1 transcellular transcytosis across T84 intestinal epithelial cells". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1782 (6): 370–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.01.010. PMC 2509583. PMID 18342638.

- ↑ Wakatsuki T, Schwab B, Thompson NC, Elson EL (March 2001). "Effects of cytochalasin D and latrunculin B on mechanical properties of cells". Journal of Cell Science. 114 (Pt 5): 1025–36. doi:10.1242/jcs.114.5.1025. PMID 11181185.

- ↑ Spector I, Shochet NR, Blasberger D, Kashman Y (1989). "Latrunculins--novel marine macrolides that disrupt microfilament organization and affect cell growth: I. Comparison with cytochalasin D". Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 13 (3): 127–44. doi:10.1002/cm.970130302. PMID 2776221.

- ↑ Pendleton A, Koffer A (January 2001). "Effects of latrunculin reveal requirements for the actin cytoskeleton during secretion from mast cells". Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 48 (1): 37–51. doi:10.1002/1097-0169(200101)48:1<37::aid-cm4>3.0.co;2-0. PMID 11124709.

- ↑ Yarmola EG, Somasundaram T, Boring TA, Spector I, Bubb MR (September 2000). "Actin-latrunculin A structure and function. Differential modulation of actin-binding protein function by latrunculin A". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (36): 28120–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.m004253200. PMID 10859320.

- ↑ Gronewold TM, Sasse F, Lünsdorf H, Reichenbach H (January 1999). "Effects of rhizopodin and latrunculin B on the morphology and on the actin cytoskeleton of mammalian cells". Cell and Tissue Research. 295 (1): 121–9. doi:10.1007/s004410051218. PMID 9931358. S2CID 20994479.

- ↑ Fairn GD, McMaster CR (January 2008). "Emerging roles of the oxysterol-binding protein family in metabolism, transport, and signaling". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (2): 228–36. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7325-2. PMID 17938859. S2CID 5753339.

- 1 2 Gibbon BC, Kovar DR, Staiger CJ (December 1999). "Latrunculin B has different effects on pollen germination and tube growth". The Plant Cell. 11 (12): 2349–63. doi:10.1105/tpc.11.12.2349. PMC 144132. PMID 10590163.

- 1 2 3 4 Konishi H, Kikuchi S, Ochiai T, Ikoma H, Kubota T, Ichikawa D, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Sakakura C, Sonoyama T, Kokuba Y, Sasaki H, Matsui T, Otsuji E (June 2009). "Latrunculin a has a strong anticancer effect in a peritoneal dissemination model of human gastric cancer in mice". Anticancer Research. 29 (6): 2091–7. PMID 19528469.

- ↑ Roa-Espitia AL, Hernández-Rendón ER, Baltiérrez-Hoyos R, Muñoz-Gotera RJ, Cote-Vélez A, Jiménez I, González-Márquez H, Hernández-González EO (September 2016). "Focal adhesion kinase is required for actin polymerization and remodeling of the cytoskeleton during sperm capacitation". Biology Open. 5 (9): 1189–99. doi:10.1242/bio.017558. PMC 5051654. PMID 27402964.

- ↑ Spector I, Shochet NR, Kashman Y, Groweiss A (February 1983). "Latrunculins: novel marine toxins that disrupt microfilament organization in cultured cells". Science. 219 (4584): 493–5. Bibcode:1983Sci...219..493S. doi:10.1126/science.6681676. PMID 6681676.

- ↑ Cayman chemical (2017). "SAFETY DATA SHEET Latrunculin A" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 Cheney KL, White A, Mudianta IW, Winters AE, Quezada M, Capon RJ, Mollo E, Garson MJ (2016-01-20). "Choose Your Weaponry: Selective Storage of a Single Toxic Compound, Latrunculin A, by Closely Related Nudibranch Molluscs". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0145134. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1145134C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145134. PMC 4720420. PMID 26788920.

- 1 2 3 Gillor O, Carmeli S, Rahamim Y, Fishelson Z, Ilan M (May 2000). "Immunolocalization of the Toxin Latrunculin B within the Red Sea Sponge Negombata magnifica (Demospongiae, Latrunculiidae)". Marine Biotechnology. 2 (3): 213–23. doi:10.1007/s101260000026. PMID 10852799. S2CID 1759699.

- ↑ Ayscough KR, Stryker J, Pokala N, Sanders M, Crews P, Drubin DG (April 1997). "High rates of actin filament turnover in budding yeast and roles for actin in the establishment and maintenance of cell polarity were revealed using the actin inhibitor latrunculin-A". The Journal of Cell Biology. 137 (2): 399–416. doi:10.1083/jcb.137.2.399. PMC 2139767. PMID 9128251.

- 1 2 Schubert T, Akopian A (2004). "Actin filaments regulate voltage-gated ion channels in salamander retinal ganglion cells". Neuroscience. 125 (3): 583–90. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.02.009. PMID 15099672. S2CID 34541681.

- 1 2 Houssen WE, Jaspars M, Wease KN, Scott RH (January 2006). "Acute actions of marine toxin latrunculin A on the electrophysiological properties of cultured dorsal root ganglion neurones". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Toxicology & Pharmacology. 142 (1–2): 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.09.006. PMID 16280258.

- 1 2 Khanfar MA, Youssef DT, El Sayed KA (February 2010). "Semisynthetic latrunculin derivatives as inhibitors of metastatic breast cancer: biological evaluations, preliminary structure-activity relationship and molecular modeling studies". ChemMedChem. 5 (2): 274–85. doi:10.1002/cmdc.200900430. PMC 3529144. PMID 20043312.

- 1 2 3 Sayed KA, Khanfar MA, Shallal HM, Muralidharan A, Awate B, Youssef DT, Liu Y, Zhou YD, Nagle DG, Shah G (March 2008). "Latrunculin A and its C-17-O-carbamates inhibit prostate tumor cell invasion and HIF-1 activation in breast tumor cells". Journal of Natural Products. 71 (3): 396–402. doi:10.1021/np070587w. PMC 2930178. PMID 18298079.

- ↑ Gonzalez JM, Ko MK, Pouw A, Tan JC (February 2016). "Tissue-based multiphoton analysis of actomyosin and structural responses in human trabecular meshwork". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 21315. Bibcode:2016NatSR...621315G. doi:10.1038/srep21315. PMC 4756353. PMID 26883567.

- 1 2 Rasmussen CA, Kaufman PL, Ritch R, Haque R, Brazzell RK, Vittitow JL (September 2014). "Latrunculin B Reduces Intraocular Pressure in Human Ocular Hypertension and Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma". Translational Vision Science & Technology. 3 (5): 1. doi:10.1167/tvst.3.5.1. PMC 4164113. PMID 25237590.