| Lagunaria | |

|---|---|

| |

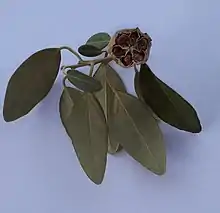

| Leaves and fruit of Lagunaria patersonia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Subfamily: | Bombacoideae |

| Genus: | Lagunaria (DC.) Rchb. |

| Species | |

|

See text. | |

Lagunaria is a genus in the family Malvaceae. It is an Australian plant which is native to Lord Howe Island, Norfolk Island and parts of coastal Queensland.[1] It has been introduced to many parts of the world. The genus was named for its resemblance to the earlier genus Laguna Cav., which was named in honour of Andrés Laguna, a Spanish botanist and a physician to Pope Julius III.[2]

As of April 2021, Plants of the World Online accepts two species:[3]

- Lagunaria patersonia (Andrews) G.Don

- Lagunaria queenslandica Craven

Description

General

The tree can grow to be 10 - 15 metres tall,[4] and one and a half metres in diameter.[2] It is considered to be hardwood.[5]

Vegetative

Trunk

The trunk is straight and made of a soft, fibrous timber.[2]

Leaves

The leaves are evergreen, though they change with age.[6][7] They are a dark green colour in the earlier stages of their development, with the undersides possessing a scale like quality and are of a silver colour.[2] Both sides become a pale green colour as they age and the scaley underside becomes smooth.[2] They have an elliptical shape and become narrower as the plant starts to flower.[8] They are eight centimetres in length and three and a half centimetres in width on average.[9]

Petioles

The petiole contains multiple large internal ducts which are filled with a staining material which is secreted during cellular fixation.[1]

Extrafloral nectaries

Extrafloral nectaries are located on the underside of the petioles of younger leaves.[1] Unlike many species with extrafloral nectaries, there is no differentiated, structural secretory tissue denoting the location of the nectary region. Instead, the areas that possess secretory tissue can be seen in the density of the indumentum (a covering of fine hairs) at specific areas.[1] Areas that possess a nectary have shield-shaped trichomes (fine hairs) that are grouped closely together.[1] The nectar is produced by multicellular, glandular trichomes that arise between the shield-shaped trichomes. The non-nectary areas adjacent to the nectaries have fewer hairs that are more widely spread apart.[1]

Reproductive

Flowers

The flower fades from a deep pink colour to a white and pale pink as it ages.[7][10] It is similar in appearance to a hibiscus.[7] It has a diameter ranging from 1.5 to 3 inches.[7] Each flower normally has 3–5 petals.[11]

The flower grows from a short, thick pedicel in the axil of the leaf.[2] It blooms in the summertime,[2] between the months of October and February.[9]

The calyx have four to five lobes which are derived from the connate sepals.[7]

The petals bloom in a clockwise and/or counter clockwise direction.[11] While each flower has five petals when it is in bud, it is not uncommon for only three to four of the petals to bloom.[11]

The epicalyx is made of three to five large segments which are joined at the base.[2] These form a protective layer over the flower when it is in bud.[7][10] These segments detach as the flower develops.[11] The lower four-fifths of the sepals length are fused from the start of their development.[11] As the flower grows, the sepals unite at their apex.[11] The flower gradually opens to full bloom at irregular times. The petal aestivation is contorted, spiralling in either a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction.[11]

The petals and androecial tube are almost of identical length.[11] The androecial tube ends in three to five short sterile teeth.[11]

There are usually two filaments present.[11] These are located either very closely to each other, joined at the base or for the majority of its length.[11]

The Pollen grains measure 45–50 µm in size. They are of a sphere-like shape, and is colporate with apertures that combine around small pores and gooves. Its aperture number is 22–45.[12]

Inflorescence

The inflorescence is lightly covered in a rough scurfy texture.[2] There are three to five bracteoles that are joined in a wide, short-lobed cup.[2]

Androecium

The five-sided androecium ring wall is divided into five sections that alternate with the sepals.[11]

The androecium tube contains ten vascular bundles, each separated into pairs of two.[11] Each pair of vascular bundles stems from the base of one of the five petals that make up the flower.[11] The pair located further from the androecium centre can often form a bundle that is in the shape of a U.[11] Below the lowest filaments, a small section of each androecial sector stems into the base of the stamens.[11] The stamen is a golden colour, with the anther comprising much of its length.[7] It bears numerous filaments on the outside below the five crenate summit.[2] The stamens are positioned between the rows of each androecial sector.[11] Above this, the vascular bundles branch off until each stamen contains one vascular bundle.[11]

Gynoecium

The ovary has five cells and has several ovules in each cell.[2][10] The style is clavate at the top (club-shaped), with five radiating stigmatic lobes which are of a white, cream colour.[7]

Fruit

The fruit of the tree presents as a brown globular capsule measuring two centimetres in diameter on average.[9] The capsules contain five valves that are arranged loculicidally (splitting between each locule).[2] It is filled with seeds that are smooth, thick and kidney-shaped.[2][10] The inner wall is lined with white, barbed hairs that cause irritation to the skin when come in to contact with.[13]

Taxonomy

Taxonomic history

Lagunaria was first discovered by Colonel W. Paterson, who first sent seeds to England while stationed on Norfolk Island in 1792.[2] Paterson was only an amateur botanist, the manuscript of flora he compiled during his time there being evidence of this.[14] Paterson was on Norfolk Island between the 4th of November 1791 and the 9th of March 1793.[14]

Reichenbach was established as the authority of the genus in 1828,[1][8] as seen in the genus' full name, Lagunaria (DC.) Rchb.[15] There was controversy of the authority of the genus for a time as many attributions were misakenly to George Don.[8] It was originally categorised as being a part of the genus Hibiscus, based on a description by De Candolle in 1824.[16][8] In 1828, Reichenbach recognised it as a separate genus and recategorized it to reflect this.[8]

Species

It was originally believed to be monotypic, and was divided in to two subspecies in 1990 by P.S. Green, with L. Patersonia being from Norfolk Island and L.patersonia subsp. bracteata from Queensland.[8] In 2006 they were recognise to be two distinct species by the names of L. patersonia and L.queenslandica respectively by L.A Craven.[1] Some of the features used to distinguish the two include:

- The bracteoles do not persist at the time of flowering in Patersonia.[8]

- The leaves of Patersonia are thicker and with a more prominent white pigmented, tomentose underside.[8]

- The length of the style and the subsequent degree to which it protrudes from the flower is greater in Queenslandica.[1]

- Queenslandica has shorter petals and staminal column.[1]

- Patersonia often occurs in rainforest/swamp areas and Queenslandica is more often found in non-rainforest areas including coastlines and rivers.[1]

Phylogeny

Early categorisations of Lagunaria placed it somewhere between the sub-families Bombacoideae and Malvoideae. Phylogenetic analysis has now determined it to be a part of Malvoideae.[1]

Lagunaria is polytypic with two known species. It was able to be identified as diverging earlier in this tribe's phylogenetic tree due to it producing copious amounts of endosperm.[16]

It was previously believed to be a part of the tribe Hibisceae, however testing has revealed this is not the case.[1] It instead forms a robust clade with the Australian genus Howittia which is also a associated with other Malvoideae tribes/genera.[17] These discoveries were made in an experiment which used two chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) sequences. These sequences were a coding region (ndhF) and a non-coding region (The rpl16 intron).[16] Further cpDNA testing revealed that both Lagunaria and Howittia contain two copies of the nuclear rpb2 gene.[17]

Nomenclature

Botanical names

The accepted botanical name for the genus Lagunaria is Lagunaria (DC.) Rchb.[18] Synonyms for this name include:

Colloquial names

On Norfolk Island, Lagunaria it is commonly known as the White Oak.[14] It is also known as:

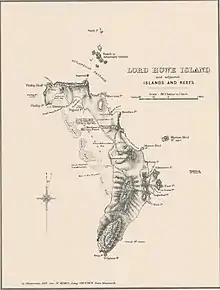

Distribution and habitat

Lagunaria is endemic to Norfolk Island, Lord Howe Island, Queensland.[1]

It tends to thrive in conditions that are humid and wet, and so has been introduced to many tropical locations around the world.[22]

It is often considered to be a pest because due to the injurious nature of the seed pods and its competition with native vegetation.[7]

It is widely cultivated throughout Australia, and can be found around the coast of New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania, Western Australia, South Australia and Victoria.[15]

It can be found in many parts of the world in areas with a warm tropical environment. Some of places it can be found are compiled below.

| Africa | New Zealand | North America | South America | Europe |

| Ethiopia[23] | Auckland[15] | Louisiana[19] | Chile[24] | Malta[20][13] |

| Kenya[25] | Nelson[15][7] | Hawaii[7] | Italy[26] | |

| Libya[25] | Napier[15] | Lake Charles[19] | ||

| Egypt[12] | Hibiscus Coast[15] | Albany[19] | ||

| Motueka[15] | California[7][23] | |||

| Wellington[7] | Costa Rica[7] | |||

| Northern New Zealand[23] | Floria[7] |

Ecology

_(8600292294).jpg.webp)

Lagunaria is fed upon by Hibiscus Harlequin Bug.[27] The females are known to deposit their eggs around the bases of the stems.[28] The insects feed on the leaves, flowers fruit and seeds and suck the sap from the stems.[28][29] They rarely cause significant damage to the plant.[29]

The cricket Dictyonemobius, colloquially known as the striped island dwarf cricket,[30] is known to appear around the roots and leaf litter of Lagunaria during the night.[31]

Pests and diseases

In New Zealand around the Nelson and Wellington areas, Lagunaria suffers from a fungal pathogen called Puccinia plagianthi. It is usually associate with the plants Hoheria and Plagianthus. Lagunaria also suffers from Olive scale, a parasite that goes by Saissetia oleae, in New Zealand.[32]

Wilt disease in the form of the fungus Verticillium dahliae has spread to Lagunaria in the southern parts of Italy.[33]

Cultivation

Lagunaria has been cultivated in many greenhouses around the world due to the beauty of its flower.[34]

It has one known cultivar by the name of Lagunaria patersonia 'Royal Purple'.[19][7] It is known to be grown along the coast of California and throughout some of the inland valleys. It can also be found in Britain.[7]

It is used exclusively as an ornamental tree. It can be used as a flower display, hedge, coastal garden,[7] street or park tree,[6] just to name a few of its uses. Due to it being most commonly found on the coast, it effective a providing a wind-break and absorbing salt spray.[35]

It tends to thrive in locations that are well lit and have well-drained soil.[22][35] It is a hardy plant that can handle poor, dry soil, salt spray, wind and light frosts.[6]

It can be propagated by taking semi-ripe cutting in the summer time. It can also be grown from seed.[7]

Conservation

On Lord Howe Island, the Lagunaria Swamp Forest is listed as a critically endangered ecological community by the NSW Government under the Threatened Species Conservation Act (1995).[36] The swamp forest was originally restricted to five small areas on the island.[37] It was estimated to cover around six hectares on the island as it could only occur in the low-lands areas.[38] It is estimate around 95% of these areas were destroyed for settlement.[38][39] Some of these five specified areas have since been destroyed since this estimation.[36]

One of the major threats facing the ecological community was invasion by exotic weeds such as the cherry guava.[37] Other invasive species include ground asparagus and ehrharta erecta and tobacco bush. Other threats include wind exposure from lack of protective vegetation, cattle trampling and grazing, edge effects, alterations to water regimes and rodents.[36][40][39]

Restoration activities have been taking place since it was first listed as endangered in 2003. Some of the actions taken include habitat replanting and fencing off of remaining areas and previously occupied habitat. This has successfully reduced pressure from cattle grazing.[40] Other activities that have been done to assist Lagunaria include the removal of weeds from the swamp forest and the prevention of garden plants escaping into bushland areas.[36]

The restoration of this community is overseen by the ecological community management stream of the saving our species program.[41] None of the locations where the swamp forest exist are protected by the Lord Howe Island Board under the Lord Howe Island Permanent Park Preserve.[40]

Aboriginal Uses

Lagunaria was used by Aboriginal people as a source of fibre. From this they created fishing lines and nets, dilly bags, baskets, animal nets, string and rope.[34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Craven, L. A.; Miller, C.; White, R. G. (27 July 2006). "A New Name, and Notes on Extra-Floral Nectaries, in Lagunaria (Malvaceae, Malvoideae)". Blumea - Biodiversity, Evolution and Biogeography of Plants. 51 (2): 345–353. doi:10.3767/000651906X622283. ISSN 0006-5196.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Maiden, J. H. (Joseph Henry). "The Forest Flora of New South Wales". adc.library.usyd.edu.au. pp. 113–115. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ "Lagunaria (A.DC.) Rchb". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ↑ "The Lagunaria Page". Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ Mueller-Dombois, Dieter (2002). "Forest Vegetation across the Tropical Pacific: A Biogeographically Complex Region with Many Analogous Environments". Plant Ecology. 163 (2): 155–176. doi:10.1023/A:1020953707063. ISSN 1385-0237. JSTOR 20051320. S2CID 25434093.

- 1 2 3 Brascamp, Wilmien. "About Garden Design - Lagunaria patersonii". aboutgardendesign.com. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Hinsley, Stewart R. "The Lagunaria Page". Malcaveae Info.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Green, P. S. (1990). "Notes Relating to the Floras of Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands, III". Kew Bulletin. 45 (2): 235–255. doi:10.2307/4115682. ISSN 0075-5974. JSTOR 4115682.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Sallywood (Lagunaria patersonia)". www.lhimuseum.com. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Flora of Victoria". vicflora.rbg.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 von Balthazar, Maria; Alverson, William S.; Schönenberger, Jürg; Baum, David A. (2004). "Comparative Floral Development and Androecium Structure in Malvoideae (Malvaceae s.l.)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 165 (4): 445–473. doi:10.1086/386561. ISSN 1058-5893. JSTOR 10.1086/386561. S2CID 84446601.

- 1 2 Naggar, Salah M. El (6 April 2004). "Pollen Morphology of Egyptian Malvaceae: An Assessment of Taxonomic Value". Turkish Journal of Botany. 28 (1–2): 227–240. ISSN 1300-008X.

- 1 2 Borg, Joseph (2009). "Maltese Masterpiece". Historic Gardens Review (21): 26–29. ISSN 1461-0191. JSTOR 44789788.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Nan (2005). "William Paterson: AMATEUR COLONIAL BOTANIST, 1755-1810". Australian Garden History. 17 (1): 8–10. ISSN 1033-3673. JSTOR 44179271.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Australia, Atlas of Living. "Genus: Lagunaria". bie.ala.org.au. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 Pfeil, B. E.; Brubaker, C. L.; Craven, L. A.; Crisp, M. D. (2002). "Phylogeny of Hibiscus and the Tribe Hibisceae (Malvaceae) Using Chloroplast DNA Sequences of ndhF and the rpl16 Intron". Systematic Botany. 27 (2): 333–350. ISSN 0363-6445. JSTOR 3093875.

- 1 2 Pfeil, B. E.; Brubaker, C. L.; Craven, L. A.; Crisp, M. D. (1 July 2004). "Paralogy and Orthology in the Malvaceae rpb2 Gene Family: Investigation of Gene Duplication in Hibiscus". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (7): 1428–1437. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh144. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 15084680.

- ↑ "Lagunaria". International Plant Names Index. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "PlantFiles: Norfolk Island Hibiscus, Cow Itch Tree, Pyramid Tree, Queensland Pyramid Tree". Dave's Garden. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Mifsud, Stephen (23 August 2002). "Lagunaria patersonii (Primrose Tree) : MaltaWildPlants.com - the online Flora of the Maltese Islands". www.maltawildplants.com. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Barley, Richard (1990). "Availability of Australian Plants in the Nursery Trade in Victoria during the Nineteenth Century". Australian Garden History. 2 (3): 17–19. ISSN 1033-3673. JSTOR 44178178.

- 1 2 "Lagunaria patersonia". anpsa.org.au. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Lagunaria patersonia (Andrews) G. Don". Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Figuero, Javier A. (2016). "Vascular flora in public spaces of Santiago, Chile". Gayana. Botánica. 73: 85–103. doi:10.4067/S0717-66432016000100011.

- 1 2 "CJB - African plant database - Detail". www.ville-ge.ch. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Aiello, D.; Parlavecchio, G.; Vitale, A.; Lahoz, E.; Nicoletti, R.; Polizzi, G. (4 April 2008). "First Report of Damping-Off Caused by Rhizoctonia solani AG-4 on Lagunaria patersonii in Italy". Plant Disease. 92 (5): 836. doi:10.1094/PDIS-92-5-0836A. ISSN 0191-2917. PMID 30769610.

- ↑ Fabricant, Scott A.; Smith, Carolynn L. (2014). "Is the hibiscus harlequin bug aposematic? The importance of testing multiple predators". Ecology and Evolution. 4 (2): 113–120. doi:10.1002/ece3.914. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 3925375. PMID 24558567.

- 1 2 Giffney, Raelene A.; Kemp, Darrell J. (2014). "Does it Pay to Care?: Exploring the Costs and Benefits of Parental Care in the Hibiscus Harlequin Bug Tectocoris diophthalmus (Heteroptera: Scutelleridae)". Ethology. 120 (6): 607–615. doi:10.1111/eth.12233. ISSN 1439-0310.

- 1 2 "Australian Native Hibiscus". www.anpsa.org.au. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ↑ "ADW: Dictyonemobius: CLASSIFICATION". animaldiversity.org. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ Otte, Daniel; Rentz, D. C. F. (1985). "The Crickets of Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands (Orthoptera, Gryllidae)". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 137 (2): 79–101. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4064861.

- ↑ "The Lagunaria Page". www.malvaceae.info. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ↑ Polizzi, G. (1996). "Wilt of Lagunaria patersonii caused by Verticillium dahliae [Italy]". Colture Protette (in Italian). ISSN 0390-0444.

- 1 2 Mitchell, Andrew S. (1982). "Economic Aspects of the Malvaceae in Australia". Economic Botany. 36 (3): 313–322. doi:10.1007/BF02858556. ISSN 0013-0001. JSTOR 4254404. S2CID 29716377.

- 1 2 "Lagunaria patersonia". www.gardensonline.com.au. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Lagunaria Swamp Forest on Lord Howe Island - profile | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- 1 2 Brown, Dianne; Baker, Lynn (30 April 2009). "The Lord Howe Island Biodiversity Management Plan: An integrated approach to recovery planning". Ecological Management & Restoration. 10: S70–S78. doi:10.1111/j.1442-8903.2009.00449.x.

- 1 2 Pickard, J (1983). "Vegetation of Lord Howe Island". Cunninghamia. 1: 133–265.

- 1 2 Auld, T.; Hutton, I. (2004). "Conservation issues for the vascular flora of Lord Howe Island". Cunninghamia. 8 (4): 490–500. S2CID 55463863.

- 1 2 3 Major, Richard (13 August 2010). "Lagunaria Swamp Forest on Lord Howe Island - critically endangered ecological community listing". NSW Environment, Energy and Science. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ "Lagunaria Swamp Forest on Lord Howe Island | Conservation project | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 20 May 2021.