| Lagonimico | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Pitheciidae |

| Subfamily: | Callicebinae |

| Genus: | †Lagonimico Kay 1994 |

| Species | |

| |

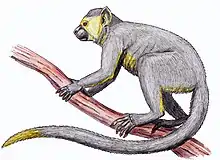

Lagonimico is an extinct genus of New World monkeys from the Middle Miocene (Laventan in the South American land mammal ages; 13.8 to 11.8 Ma). Its remains have been found at the Konzentrat-Lagerstätte of La Venta in the Honda Group of Colombia. The type species is L. conclucatus.[1]

Description

A nearly complete but badly crushed skull and mandible of Lagonimico were discovered in the La Victoria Formation, that has been dated to the Laventan, about 13.5 to 12.9 Ma.[2][3] Lagonimico, as Micodon and Patasola magdalenae, also from the Honda Group, have been attributed to the Callitrichinae.[4]

Features of the dentition suggest Lagonimico is a sister group to living Callitrichinae (Saguinus, Leontopithecus, Callithrix, and Cebuella). These features include having elongate compressed lower incisors, a reduced P2 lingual moiety, and the absence of upper molar hypocones. The new taxon also has a relatively deep jaw, that rule it out of the direct ancestry of any living callitrichine.[3]

The orbits of L. conclucatus are small, suggesting diurnal habits. Inflated, low-crowned (bunodont) cheek teeth with short, rounded shearing crests, as well as premolar simplification and M3 size reduction, suggest fruit- or gum eating adaptations, as among many living callitrichines. Procumbent and slightly elongate lower incisors suggest this species could use its front teeth as a gouge, perhaps for harvesting tree gum. Estimates from jaw size suggest Lagonimico weighed about 1,200 to 1,300 grams (2.6 to 2.9 lb),[3][5] about the size of Callicebus, the living titi monkey of South America.[6] Later research reduced the estimated weight to 595 grams (1.312 lb).[7] Judged from tooth size and jaw length, Lagonimico would have been slightly smaller than Callicebus, but still larger than Callimico or any living callitrichine.[3]

The upper first molar (M1) with a subtriangular outline with a narrow lingual side resembles that of the oldest New World primate discovered to date, the Late Eocene Perupithecus from the Peruvian Amazon.[8]

Habitat

The Honda Group, and more precisely the "Monkey Beds", are the richest site for fossil primates in South America.[9] Other than most fossil primates found at La Venta, the specimens of Lagonimico do not come from the "Monkey Beds".[10] It has been argued that the monkeys of the Honda Group were living in habitat that was in contact with the Amazon and Orinoco Basins, and that La Venta itself was probably seasonally dry forest.[11] The evolutionary separation from Aotus of Lagonimico has been placed in the Early Miocene at 17.5 Ma.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Lagonimico conclucatus at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Defler, 2004, p.32

- 1 2 3 4 Kay, 1994, p.333

- ↑ Takai et al., 2001, p.290

- ↑ Pérez et al., 2013, p.9

- ↑ Tejedor, 2013, p.29

- ↑ Silvestro et al., 2017, p.14

- ↑ Bond et al., 2015, p.538

- ↑ Rosenberger & Hartwig, 2001, p.3

- ↑ Wheeler, 2010, p.137

- ↑ Lynch Alfaro et al., 2015, p.520

- ↑ Takai et al., 2001, p.304

Bibliography

- Bond, Mariano; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Kenneth E. Campbell Jr.; Laura Chornogubsky; Nelson Novo, and Francisco Goin. 2015. Eocene primates of South America and the African origins of New World monkeys. Nature 520. 538–546. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Defler, Thomas. 2004. Historia natural de los primates colombianos, 1–613. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Kay, Richard F. 1994. "Giant" tamarin from the Miocene of Colombia. Physical Anthropology 95. 333–353. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Lynch Alfaro, Jessica W.; Liliana Cortés Ortiz; Anthony Di Fiore, and Jean P. Boubli. 2015. Special issue: Comparative biogeography of Neotropical primates. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82. 518–529. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Pérez, S. Iván; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Nelson M. Novo, and Leandro Aristide. 2013. Divergence Times and the Evolutionary Radiation of New World Monkeys (Platyrrhini, Primates): An Analysis of Fossil and Molecular Data. PLOS One 8. 1–16. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Rosenberger, Alfred L., and Walter Carl Hartwig. 2001. New World Monkeys. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences _. 1–4. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Silvestro, Daniele; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Martha L. Serrano Serrano; Oriane Loiseau; Victor Rossier; Jonathan Rolland; Alexander Zizka; Alexandre Antonelli, and Nicolas Salamin. 2017. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data. BioRxiv _. 1–32. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Takai, Masanaru; Federico Anaya; Hisashi Suzuki; Nobuo Shigehara, and Takeshi Setoguchi. 2001. A New Platyrrhine from the Middle Miocene of La Venta, Colombia, and the Phyletic Position of Callicebinae. Anthropological Science, Tokyo 109.4. 289–307. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Tejedor, Marcelo F. 2013. Sistemática, evolución y paleobiogeografía de los primates Platyrrhini. Revista del Museo de La Plata 20. 20–39. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Wheeler, Brandon. 2010. Community ecology of the Middle Miocene primates of La Venta, Colombia: the relationship between ecological diversity, divergence time, and phylogenetic richness. Primates 51.2. 131–138. Accessed 2017-09-24.

Further reading

- Fleagle, John G., and Alfred L. Rosenberger. 2013. The Platyrrhine Fossil Record, 1–256. Elsevier ISBN 9781483267074. Accessed 2017-10-21.

- Hartwig, W.C., and D.J. Meldrum. 2002. The Primate Fossil Record - Miocene platyrrhines of the northern Neotropics, 175–188. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08141-2. Accessed 2017-09-24.