| Preceded by the Pleistocene |

| Holocene Epoch |

|---|

|

|

Blytt–Sernander stages/ages

*Relative to year 2000 (b2k). †Relative to year 1950 (BP/Before "Present"). |

The Kurumchi culture or the "Kurumchi blacksmiths" (Russian: Курумчинские кузнецы) was the earliest Iron Age archaeological culture of Baikalia as proposed by Bernhard Petri.[1][2] He also speculated that they were the progenitors of the Sakha people, a claim that didn't go unchallenged by his contemporaries. Petri assumed that the Kurumchi left Baikalia for the Middle Lena due to pressure from the ancestors of the Buryats.[3]

Alexey Okladnikov was a student of Petri who expanded scholarship on the Kurumchi. He connected them to the Kurykans, a people mentioned in Chinese historical sources. Kurumchi society was conceived as analogous to the Yenisei Kyrgyz,[4] being composed of "simple people and the aristocrats."[5]

Starting in the 1990s scholars have begun to challenge the claims made by Petri and Okladnikov. Bair Dashibalov concluded that Petri's findings come from a wide chronological period ranging from the 9th-14th centuries C.E.[6]

Background

In 1912 the Russian Committee for the Study of Central and East Asia sent Bernhard Petri to Irkutsk. He was an employee of the Kunstkamera from 1910 until 1917.[7] Petri was directed to document the social and material culture of the Buryats along with their religious beliefs. He was also instructed to seek out and discover ancient artifacts, so he initiated archaeological digs in the Murin River valley in the contemporary Ekhirit-Bulagatsky District of the Ust-Orda Buryat Okrug.[8] During the late Russian Empire, itas located within the Kurumchi khoshun and was sometimes called the Kurumchi Valley.[9]

Previously an educator named O. A. Monastyreva found a spindle whorl inscribed with Old Turkic script (described below) outside modern Narin-Kunta. Monastyreva assisted Petri in digging at this location, which was the primary focus of the year. Among the initial findings there were pottery shards and a small forge that Petri illustrated.[10] In the following year he returned and expanded upon the excavation sites.[11]

In 1916 Petri explored cave systems in Olkhon Island. Their entrances were barricaded with rocks in such way to only allow movement by crawling. They were perhaps seasonally inhabited only when dry during the winter months.[2] Among the discoveries were flat stone slabs used to create graves arranged in a row. Their appearance was compared to Buryat yurts by Petri[12] and later by Okladnikov to also be similar to Evenki dwellings called dzhu: джу[13]

Mikhail Ovchinnikov

Mikhail P. Ovchinnikov was a self-taught archaeologist who hypothesized the predecessors of the Sakha once inhabited Baikalia. He found evidence of iron and copper smithing along with caches of iron ore deposited in pits in the region. Some Sakha informants spoke of their ancestors being forced from Lake Baikal to the north and during this movement abandoned the Old Turkic alphabet.[14] Ovchinnikov concluded that the ancestral Sakha migrated from Baikalia to the Lena during the time of Chinggis Khan.[15]

In 1918 Petri became acquainted with Ovchinnikov at the Irkutsk city museum. They shared their archaeological findings and conclusions about the ancient history of Eastern Siberia. Petri reported that a frequent topic discussed was the origins of the Sakha. These conversations were "jokingly dubbed" the "Yakut problem" as the two scholars speculated on the Sakha ethnogenesis.[16]

Kurumchi blacksmiths

In the 1920s Bernhard Petri published his interpretation of the artifacts found in the Murin River valley. He concluded that a hitherto unknown society produced the archeological remains. Iron items were discovered in their settlements which led to Petri calling them the "Kurumchi blacksmiths."[16][1][2] A pupil of Petri's, Pavel Khoroshikh, stated the research performed by his teacher substantiated the southern origin of the Sakha people theory previously proposed by Vladimir I. Ogorodnikov, Mikhail P. Ovchinnikov, and Wacław Sieroszewski.[1] He also noted the similarities between pottery discovered in the Murin River Valley and Olkhon Island.[17] In autumn 1923 Petri led an expedition to Lake Khövsgöl and found ceramic remains he considered from the Kurumchi.[18][19]

Territory

Petri saw Lake Baikal as the center of Kurumchi activity. He proposed that their northern cultural boundary was formed by the Lena headwaters, contemporary Balagansk on the Angara, and the river mouth of the Kichera; while the southern ran from modern Tunka to the Uda.[20][2]

Iron smithing

According to Petri the Kurumchi were sophisticated blacksmiths. While their iron kettles were of Chinese origin,[2] they were capable of repairing cracks with external patches. Kurumchi cliff drawings include figures possibly adorned in chainmail.[13] Okladnikov detailed the Kurumchi iron-smithing techniques:

"The furnace had the appearance of a large thick-walled vessel with a round bottom. In the pot there were two openings for nozzles, and it also contained ore and charcoal in layers. During smelter, air was forced into the vessel through the nozzle with bellows attached, and from above coal and softened [preheated] ore were gradually added. In the process of smelting, the iron settled, and a large iron ingot was formed, its lower part rounded and the upper surface flat."[21]

Old Turkic writing

Two coal spindle whorls with a diameter of 3.5–6 cm[23] inscribed with Old Turkic script were discovered in Baikalia. Petri studied the items, considering them to be Kurumchi products,[24] and published an article about them in 1922.[25]

An assistant and student of Petri, Gavriil Ksenofontov,[22] characterized the findings as random discoveries found by non-archaeologists.[26] As of 2019 they are reportedly lost and only photographs remain.[27]

Narin-Kunta spindlewhorl

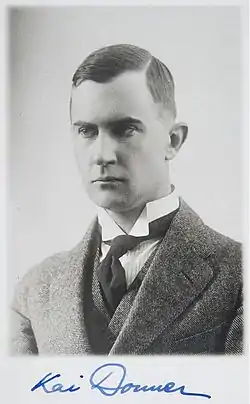

—Kai Donner & Martti Räsänen (1932)

The first spindlewhorl was found outside the village of Narin-Kunta. It was discovered by an educator, O. A. Monastyreva, in their garden bed.[32] This location became the principal dig for the Kurumchi culture during the 1910s.[33] Donner and Räsänen[28] presented a translation which was subsequently accepted by most researchers.[34][35][36][37]

Shokhtoy spindlewhorl

—Vladimir V. Tishin (2019)

The second spindlewhorl was discovered by farmers plowing a field near Shokhtoy. As it was found by happen-stance outside of an orderly archaeological dig Ksenofontov didn't consider the Kurumchi as the probable creators of the item.[32] Donner and Räsänen were only able to distinguish some of the eroded characters. They offered "the fifth of the snowy month" and "the fifth month of the arqar year" as partial translations.[42] Later Ksenofontov,[46] Malov,[41] Orkun,[37] and Bazin[47] offered their own interpretations of the partial text. In 2019 Tishin made a comprehensive translation.[38]

Husbandry

Despite the limited pastures of Baikalia, Petri conceived that the Kurumchi were pastoralists.[48] Cattle and horse bone fragments have been recovered and both were common subjects in cliff artwork attributed to them. Equestrian herds were speculated to originate from the Yenisei steppe and not the Mongolian Plateau.[4] The appearance of Bactrian camels in supposed Kurumchi artwork made Okladnikov speculate about possible connections to the steppe cultures of Inner Asia.[13]

Agriculture

According to Petri, the Kurumchi created fortified places of habitation in bountiful meadows and pastures or strategic positions overlooking valleys.[49] Their settlements were inhabited either permanently or seasonally. Garden beds placed outside ancient stockades in the Angara watershed nearby Kulakova were claimed by Okladnikov to be Kurumchi constructions, who further considered them the first society practice agriculture in Baikalia.[13]

Irrigation was considered to have been practiced to bolster the productivity of certain pastures. One surviving series of ancient ditches is 4.6 km outside Ust-Ordynsky starting near Ulan-Zola-Tologoy (Russian: Улан-Зола-Тологой). Two 5 km long irrigation canals were placed 100-150m apart and dug up to 1 meter deep. Secondary lines were made off of the main lines to water additional fields. From the waterfalls of the Idyga (Russian: Идыга) the channels approached the right bank of the Kuda. A fortified position was found near the fields apparently created to block access to them.[13]

Hunting

Game animals likely were an important food source for the Kurumchi. The most commonly found animal remains in supposed Kurumchi settlements were elk and roe deer while sites on Olkhon Island have sheep bones present. On the Upper Lena outside Kachug are depictions of goats and elk being hunted. Birds appear highly stylized and were likely inspired by waterfowl like geese and swans. Artwork made about hunting includes figures utilizing lassos and nets. While both were commonly employed by steppe cultures Okladnikov claimed neither was used in Baikalia before the Kurumchi.[13]

Protigenitors of the Sakha

Formulation

Petri proposed that the Kurumchi were the ancestors of the Sakha people. This was based on three points:[50]

- Unlike the modern Tungustic and Buryat inhabitants of Western Baikalia, the Kurumchi "made excellent pots with a flat bottom and decorated them with patterns." The Sakha were praised as "great masters" of firing pots.

- Kurumchi dwellings are similar to балаҕан (Russian: Балаган), traditional Sakha log yurts.

- Two spindle whorls were found with Old Turkic inscriptions in Western Baikalia.

He found additional commonalities between the Kurumchi and Sakha in their equestrian equipment like stirrups and bridles, along with their arrows, knives, and humpback scythes (Russian: Коса-горбуша).[51]

Petri concluded the following:

In addition, all the data suggests that the culture of the "Kurumchi blacksmiths" is very similar to the culture of the Yakuts. This gives us the right to make a cautious assumption that the unknown people "Kurumchi blacksmiths" are none other than the ancestors of the Yakuts. In making such an assumption, we must not forget that it is far from being proven, and that all our data, unfortunately, are only shaky indications of the possibility of our assumption.[52]

Early criticism

In 1926 archivist and historian Efim D. Strelov wrote a critique of Petri's conclusions.[53] He noted the Sakha lacked spindle whorls and weaving skills entirely. More definitive proof such as specific burial traditions was seen as necessary to establish the existence of the Kurumchi.[54] Petri had compared the Kurumchi and Sakha using eleven analogies to which Strelov made his own counter-arguments.[55] Strelov concluded that the Kurumchi culture was not related to the Sakha.[56]

| Number | Proposed ties by Petri | Counterpoints by Strelov |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | They had similar pottery ornamentation patterns. | Kurumchi ceramic patterns were only vaguely defined with characteristics that could potentially be found among unrelated peoples in varying locations. |

| 2. | Women were the primary ceramic workers in both societies. | There have been a multitude of societies with women pottery workers. |

| 3. | Kurumchi and Sakha cattle had both interbred with yaks. | Strelov presented evidence that there has been no admixture between yaks and Sakha cattle. |

| 4. | Arrows from the Irkutsk museum collections and the Sakha both have forked ends which was considered a distinctive trait. | The forked end was a widespread arrow design among the Siberian Indigenous. No such arrows were found at Kurumchi sites. |

| 5. | Kurumchi blades are identical to a Sakha knife illustrated in Wacław Sieroszewski's 12 years in the Yakut country. | Sieroszewski himself found Sakha blades broadly related to examples from a variety of cultures. |

| 6. | Horseshoes found at Kurumchi sites resemble Sakha made ones. | The Sakha lacked a word for horseshoe and adopted the Russian: подкова. |

| 7. | Sakha made scythes (Russian: Коса-горбуша) are similar to an example attributed to the Kurumchi. | Sakha scythes clearly originate from Russian designs.[lower-alpha 1] |

| 8. | Scissors found at Kurumchi sites share the same shape with Sakha ones. | Sakha scissors were the same as those used by Russian peasants of the Irkutsk oblast. |

| 9. | The Kurumchi smoked from Chinese shaped iron pipes and the Sakha made identical items. | Contemporary iron pipes among the Sakha were introductions from Chinese and Koreans workers of the Olyokma and Vitim gold mines. Their smoking pipes were traditionally made of wood with copper or bone bowls. |

| 10. | Both groups made utensils made of birch bark and horsehair. | Manufacture of horse hair and birch utensils was common among the Siberian Indigenous. |

| 11. | Sakha wooden yurts (Yakut: Балаҕан) and Kurumchi dwellings were both dug into the group and quadrangular in shape. | Sakha yurts were never dug deep enough require steps. Quadrangular structures also existed among the Nanai and Ulch Tungusic peoples of the Amur. |

Another rebuttal came from Vasily I. Podgorbunsky who was a once a student of Petri.[58] In 1928 he claimed the Sakha and Kurumchi were entirely unrelated and found their ceramics dissimilar. Podgorbunsky did however consider the Sakha descendants from certain Turkic peoples.[55] This was based upon Iron Age pottery fragments found in 1917 during archaeological work performed in the Transbaikal Oblast and Irkutsk Governorate. The Sakha style pottery was claimed to have existed across Baikalia, Transbaikalia, the Mongolian Steppe, and the Yenisey watershed.[59]

Alexey Okladnikov

Okladnikov defended the hypothesis that the Kurumchi were the Sakha progenitors. The early 11th century C.E. was speculated to be when Mongolic peoples migrated to Lake Baikal. The displaced Kurumchi were forced to travel the Lena, eventually reaching the modern [60] He further found similarities between Kurumchi and Sakha pottery traditions.[61]

Modern consensus

In the 1990s Bair Dashibalov began a reexamination of the Kurumchi findings of Petri by using comparative analysis of other Siberian archaeological cultures. The Lake Khövsgöl pottery fragments were assessed as too incomplete to demonstrate Kurumchi origin.[62] According to Petri the assorted Murin river valley artifacts were created by the Kurumchi no later than the 12th century C.E.[63] Kurumchi stirrups are similar to generalized Eurasian-produced ones from the end of the 1st millennium C.E.[64] In particular older stirrups are analogous to 8th-9th centuries C.E. Saltovo-Mayaki culture stirrups,[65] while other stirrups are comparable to those utilized by the Mongolian Empire during the 13th-14th centuries C.E.[66] Certain Kurumchi arrowheads are stylistically similar to findings from the 9th-10th century C.E. Yenisei Kirghiz,[67] while others resemble ones produced by the Askizsky and Jurchens during the 11th-12th centuries C.E.[68][66] Dashibalov concluded that the Murin river valley artifacts come from a wide chronological that ranges from the 9th-14th centuries C.E.[6] This analysis have subsequently been accepted by some scholars.[69][70]

According to Vladimir Tishin the two spindle whorls with Old Turkic inscriptions were produced locally between the mid-9th to 12th centuries C.E. However their discovery outside of archaeological digs by non-professionals[26] and poor documentation by Petri made their specific cultural origins impossible to categorize.[71]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 Petri 1923a.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Petri 1928a, pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Petri 1923a, pp. 62–64.

- 1 2 Okladnikov 1976, p. 33.

- ↑ Okladnikov 1970, pp. 313–317.

- 1 2 Dashibalov 1994, pp. 20–25.

- ↑ Sirina 1999, p. 75.

- ↑ Sirina 1999, p. 62.

- ↑ Melkheev 1969, p. 138.

- ↑ Petri & Mikhailov 1913, p. 108.

- ↑ Petri 1914.

- ↑ Petri 1916, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Okladnikov 1970, pp. 306–313.

- ↑ Ushnitskiy 2016a, pp. 151–153.

- ↑ Ovchinnikov 1897.

- 1 2 Petri 1922a.

- ↑ Khoroshikh 1924, p. 41.

- ↑ Sirina 1999, p. 63.

- ↑ Petri 1926a, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Petri 1922a, p. 25.

- ↑ Okladnikov 1970, pp. 306–307.

- 1 2 Petri 1928a, p. 5.

- ↑ Petri 1923a, p. 13.

- ↑ Donner & Räsänen 1932.

- ↑ Petri 1922a, p. 39.

- 1 2 Ksenofontov 1992, p. 103.

- ↑ Tishin 2019, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 Donner & Räsänen 1932, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Clauson 1972, p. 604.

- ↑ Clauson 1972, p. 88-89.

- ↑ Tishin 2019, pp. 40–42.

- 1 2 Ksenofontov 1933, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Petri 1928a.

- ↑ Malov 1936, p. 276.

- ↑ Clauson 1972, p. 92.

- ↑ Bazin 1991, pp. 392, 498.

- 1 2 3 Orkun 1994, pp. 350–351.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tishin 2019, pp. 43–46.

- ↑ Clauson 1972, p. 75.

- ↑ Clauson 1972, p. 566.

- 1 2 3 4 Malov 1936, pp. 276–278.

- 1 2 3 4 Donner & Räsänen 1932, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Shcherbak 1961, p. 171.

- ↑ Orkun 1994, p. 341.

- ↑ Clauson 1972, pp. 261–262.

- ↑ Ksenofontov 2005, pp. 59–63.

- ↑ Bazin 1991, p. 499.

- ↑ Petri 1928a, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Petri 1928a, p. 67.

- ↑ Petri 1928a, p. 61-62.

- ↑ Petri 1928a, p. 60.

- ↑ Petri 1928a, p. 63.

- ↑ Strelov 1926.

- ↑ Strelov 1926, p. 13.

- 1 2 Dashibalov 2003, pp. 84–87.

- ↑ Strelov 1926, p. 25.

- ↑ Dashibalov 2003, p. 85.

- ↑ Sirina 1999, pp. 77–80.

- ↑ Podgorbunsky 1928, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Okladnikov 1970, p. 334.

- ↑ Okladnikov 1970, p. 330.

- ↑ Dashibalov 1994, p. 191.

- ↑ Petri 1923a, p. 14.

- ↑ Kyzlasov 1969, p. 20.

- ↑ Pletneva 1967, p. 167.

- 1 2 Dashibalov 1994, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Khudyakov 1980, p. 107.

- ↑ Kyzlasov 1983, p. 45.

- ↑ Tishin 2019, p. 42.

- ↑ Ushnitskiy 2016b, p. 175.

- ↑ Tishin 2019, p. 50.

Bibliography

Books

- Bazin, Louis (1991). Les systèmes chronologiques dans le monde turc ancient [Chronological Systems in the Ancient Turkic world] (in French). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- Clauson, Gerard (1972). An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth-Century Turkish. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- Dashibalov, Bair B. (1994). "Находки культуры «курумчинских кузнецов» из раскопок Б.Э. Петри" [Findings of the "Kurumchi smiths" culture from B.E. Petri's excavations]. Этнокультурные процессы в Южной Сибири и Центральной Азии в I-II тысячелетии н.э. [Ethnocultural processes in South Siberia and Central Asia in the I-II Millennium AD] (in Russian). Kemerovo. pp. 190–207. ISBN 5-202-00032-4. Archived from the original on 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dashibalov, Bair B. (2003). "НА БАЙКАЛЬСКИХ БЕРЕГАХ: «Якутская проблема» в археологии Прибайкалья" [ON THE BAYKAL SHORES: The "Yakut Problem" in the Archaeology of the Baikal Region]. Истоки: от древних хори-монголов к бурятам. Очерки [Origins: from the ancient Hori-Mongols to the Buryats. Essays] (in Russian). Buryat Scientific Center of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 5-7925-0127-0.

- Khudyakov, Yuliy S. (1980). Вооружение енисейских кыргызов VI-XII вв [Armament of the Yenisei Kyrgyz from the VI-XII centuries] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 2021-11-21. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Kobeleva, O. N.; Skvortsova, M. A.; Sivushkova, T. O.; Permyakov, D. V. (2013). «ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ АРХИВ ИРКУТСКОЙ ОБЛАСТИ» ПУТЕВОДИТЕЛЬ ПО ФОНДАМ ЛИЧНОГО ПРОИСХОЖДЕНИЯ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОГО АРХИВА ИРКУТСКОЙ ОБЛАСТИ ["State Archive of the Irkutsk region" Guide to the funds of personal origin of the Archive of the Irkutsk Region] (in Russian). Irkutsk.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ksenofontov, Gavriil V. (1992). Ураанхай-сахалар. Очерки по древней истории якутов [Uraanghai-Sakhalar. Essays on an Early History of Yakuts] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Yakutsk: National Press of Republic Yakutia (Sakha).

- Kyzlasov, Leonid R. (1969). История Тувы в средние века [History of Tuva in the Middle Ages] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Publishing House of Moscow State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-24. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Kyzlasov, Leonid R. (1983). Аскизская культура Южной Сибири X-XIV вв [Askiz culture of Southern Siberia X-XIV centuries]. Материалы и исследования по археологии СССР (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Melkheev, M. N. (1969). Географические названия Восточной Сибири [Geographical names of Eastern Siberia] (in Russian). Irkutsk: East-Siberian Book Publishing House.

- Okladnikov, Alexey P. (1976). История и культура Бурятии [The History and Culture of Buryatia] (in Russian). Ulan-Ude: Buryat Book Publishing House.

- Okladnikov, Alexey P. (1970). Michael, Henry N. (ed.). Yakutia: Before its incorporation into the Russian State. Anthropology of the North: Translations from Russian Sources. Montreal & London: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-9068-7.

- Orkun, Hüseyin N. (1994). Eski Türk yazıtları [Old Turkic Inscriptions] (in Turkish). Ankara: Turkish Historical Society Press.

- Ovchinnikov, Mikhail Pavlovich (1897). Из материалов по этнографии якутов [From the materials on the ethnography of the Yakuts]. Этнографическое обозрение (in Russian).

- Petri, Bernhard E. (1922a). Далекое прошлое Бурятского края [The distant past of the Buryat region] (in Russian). Irkutsk: Irkutsk State University.

- Petri, Bernhard E. (1926a). Древности озера Косогола (Монголия) [Antiquities of Lake Khövsgöl (Mongolia)] (in Russian). Irkutsk: Irkutsk State University. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Petri, Bernhard E. (1928a). "VI. Железный период" [VI. Iron Period]. Далекое прошлое Прибайкалья: научно-популярный очерк (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Irkutsk: Irkutsk State University. pp. 55–70. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Pletneva, Svetlana A. (1967). От кочевий к городам. Салтово-маяцкая культура [From nomad camps to cities. Saltovo-Mayaki culture] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Shcherbak, A. M. (1961). "Названия домашних и диких животных в тюркских языках" [Names of Domestic and Wild Animals in Turkic Languages]. Историческое развитие лексики тюркских языков [A Historical Development of the Turkic Lexicon] (in Russian). Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House. pp. 82–172.

- Sirina, Anna A. (1999). "Забытые страницы сибирской этнографии: Б.Э. Петри" [Forgotten pages of Siberian ethnography: B. E. Petri]. In Tumarkin, Daniil D. (ed.). Репрессированные этнографы [Repressed ethnographers] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Vostočnaja literatura. pp. 57–80. ISBN 5020180580. OCLC 613893817. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-10-09. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

Articles

- Donner, Kai; Räsänen, Martti (1932). "Zwei neue türkische Runenin-schriften" [Two New Turkic Runic Inscriptions]. Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne (in German). 45 (2): 1–7.

- Khoroshikh, Pavel P. (1924). "Исследования каменного и железного века Иркутского края (остров Ольхой)" [Studies of the Stone and Iron Ages of the Irkutsk Territory (Olkhoy Island)]. Известия Биолого-географического научно-исследовательского института при Государственном Иркутском университете (in Russian). Irkutsk State University. 1 (1).

- Kochnev, D. A. (1899). "Очерки юридического быта якутов" [Essays on the legal life of the Yakuts]. Proceedings of the Society of Archeology, History, Ethnography at the Imperial Kazan University. Imperial Kazan University. 15 (2).

- Kolesnik, Lyudmila; Pushkina, Tatyana L.; Svinin, Vladimir V. (2012). "ВСОРГО и музейное дело в Иркутске" [VSORGO and museum work in Irkutsk]. История (in Russian). Irkutsk Regional Museum of Local Lo. 2 (3–2): 44–56.

- Ksenofontov, Gavriil V. (1933). "Расшифровка двух памятников орхонской письменности из западного Прибайкалья М. Ресененом" [Decipherment of Two Orkhon Writing Monuments from Western Baikal Region made by M. Räsänen]. Yazyk I Myshlenie (in Russian). 1: 170–173.

- Ksenofontov, Gavriil V. (2005). "Письмена древнетюркского населения Предбайкалья: рукописи из архива" [Written Monuments of the Old Turkic Population in Western Baikal Region]. Ilin (in Russian). 5: 55–66.

- Malov, S. (1936). "Новые памятники с турецкими рунами" [New Turkic Monuments Containing Runes]. Yazyk I Myshlenie (in Russian). Moscow, Leningrad. 6–7: 251–279.

- Petri, Bernhard E.; Mikhailov, Vasily A. (1913). "Отчет о командировке Б. Э. Петри и В. А. Михайлова" [Report on the trip of B. E. Petri and V. A. Mikhailov] (PDF). Известия Русского Комитета для изучения Средней и Восточной Азии в историческом, археологическом, лингвистическом и этнографическом отношениях (in Russian). Printing house of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. 2 (2): 92–110. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Petri, Bernhard E. (1914). "Вторая поездка в Предбайкалье" [The second trip to Cisbaikalia] (PDF). Известия Русского Комитета для изучения Средней и Восточной Азии в историческом, археологическом, лингвистическом и этнографическом отношениях (in Russian). Printing house of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. 2 (3): 89–107. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- Petri, Bernhard E. (1916). "Отчет о командировке на Байкал в 1916 г." [Report on a trip to Baikal in 1916]. Report of Imperial Academy of Sciences (in Russian). Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Moscow University: 138–144.

- Petri, Bernhard E. (1922b). "М. П. Овчинни ков, как археолог" [M. P. Ovchinnikov as an archaeologist]. Сибирские огни (in Russian). 4.

- Petri, Bernhard E. (1923a). "Доисторические кузнецы в Прибайкалье. К вопросу о доисторическом прошлом якутов" [Prehistoric blacksmiths in the Baikal region. On the prehistoric past of the Yakuts]. Известия Института народного образования (in Russian). Chita. 1: 62–64.

- Podgorbunsky, Vasily I. (1928). "Заметки по изучению гончарства якутов" [Notes on the study of Yakut pottery]. Сибирская живая старина (in Russian) (7): 127–144.

- Strelov, E. D. (1926). "К вопросу о доисторическом прошлом якутов / по поводу брошюры проф. Б. Э. Петри" [On the question of the prehistoric past of the Yakuts / on the booklet "Prehistoric Blacksmiths in the Baikal region" by Prof. B.E. Petri]. Саха Кескиле (in Russian) (3): 5–25.

- Tishin, Vladimir V. (2019). "Две древнетюркские рунические надписи на пряслицах с территории Западного Прибайкалья: история находок и их историко-культурное значение" [Two Old Turkic Runic Inscriptions on Spindle-Wheels from the Territory of Western Baikal Region: the History of Finds and Their Historical and Cultural Significance]. Bulletin of the Irkutsk State University. Geoarchaeology, Ethnology, and Anthropology Series. Irkutsk: Irkutsk State University. 27: 36–55. doi:10.26516/2227-2380.2019.27.36. S2CID 213996846.

- Ushnitskiy, Vasiliy V. (2016a). "Researchers of Tsarist Russia on the study of the origin of the Sakha people". Vestnik Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta (in Russian). Yakutsk: Institute of the Humanities and the Indigenous Peoples (407): 150–155. doi:10.17223/15617793/407/23. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21.

- Ushnitskiy, Vasiliy. V. (2016b). "The Problem of the Sakha People's Ethnogenesis: A New Approach". Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities and Social Sciences. 8: 1822–1840. doi:10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-8-1822-1840.

_04.jpg.webp)