| Knapdale | |

|---|---|

Keills Chapel with cross | |

| |

| Population | 2,836 (2011[1]) |

| OS grid reference | NR700747 |

| • Edinburgh | 85 mi (137 km) |

| • London | 370 mi (600 km) |

| Council area |

|

| Lieutenancy area |

|

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Knapdale (Scottish Gaelic: Cnapadal, IPA: [ˈkɾaʰpət̪əl̪ˠ]) forms a rural district of Argyll and Bute in the Scottish Highlands, adjoining Kintyre to the south, and divided from the rest of Argyll to the north by the Crinan Canal. It includes two parishes, North Knapdale and South Knapdale. The area is bounded by sea to the east and west (Loch Fyne and the Sound of Jura respectively), whilst the sea loch of West Loch Tarbert almost completely cuts off the area from Kintyre to the south.[2][3] The name is derived from two Gaelic elements: Cnap meaning hill and Dall meaning field.[4]

Knapdale gives its name to the Knapdale National Scenic Area, one of the forty national scenic areas in Scotland, which are defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure their protection from inappropriate development.[5] The designated area covers 32,832 hectares (81,130 acres) in total, of which 20,821 hectares (51,450 acres) is on land and 12,011 hectares (29,680 acres) is marine (i.e. below low tide level).[6]

Geography

| Knapdale National Scenic Area | |

|---|---|

Loch Arail in late summer, with heather in bloom | |

| Location | Argyll and Bute, Scotland |

| Area | 328 km2 (127 sq mi)[6] |

| Established | 1981 |

| Governing body | NatureScot |

The A83 runs up the eastern coastline of the area between Tarbert and Lochgilphead; the B8024 also links these two places (which lie outwith Knapdale), but does so via a much longer route along the north shore of West Loch Tarbert and the western coast of South Knapdale. Most of the western coastline of North Knapdale is accessible by two unclassified roads, although there is a gap between Kilmory and Ellary where the route is not public road.[2][3] The B8024 through Knapdale forms part of Route 78 of the National Cycle Network, which runs between Inverness and Campbeltown.[7]

The western coast of Knapdale is deeply indented by two sea lochs, Loch Sween and Loch Caolisport. The highest point within Knapdale is Stob Odhar, at 562 metres (1,844 feet) above sea level.[2][3] Alongside Stob Odhar, two other summits within Knapdale are sufficiently prominent to be categorised as Marilyns: Cruach Lusach (467 m or 1,532 ft) and Cnoc Reamhar (265 m or 869 ft),[8] however there are no summits above 600 m (2,000 ft)[lower-alpha 1] in the area.[2][3]

Places in Knapdale include:

Demographics

The United Kingdom Census 2001 reported a population of 2345 people in South Knapdale and 491 in North Knapdale, a total of 2836 for the district.[1] This represents a slight increase over the 1991 figure of 2704, when there were 439 people living in North Knapdale, and 2265 in South Knapdale.[1] Census figures for the 19th and 20th centuries show a continuing and steady decline of population in North Knapdale, from a peak of around 2700 in 1825 to under 500 in 1950. Possible boundary changes make historic comparisons for South Knapdale less certain, but this part of the region appears not to have suffered the same depopulation as the north, and even modest growth, a rise from around 1750 in 1801 to around 2700 in 1901.[9]

History

Gaels and Norwegians

In the early first millennium, following an Irish invasion, Gaelic peoples colonised the surrounding area, establishing the kingdom of Dál Riata. The latter was divided into a handful of regions, controlled by particular kin groups, of which the most powerful, the Cenél nGabráin, ruled over Knapdale, along with Kintyre, the region between Loch Awe and Loch Fyne (Craignish, Ardscotnish, Glassary, and Glenary), Arran, and Moyle (in Ulster). Dunadd, the capital of Dál Riata, was located in this region, slightly to the north of the modern day limit of Knapdale, in what was then marshland.

This Gaelic kingdom thrived for a few centuries, but was ultimately destroyed when Norse Vikings invaded, and established their own domain, spreading more extensively over the islands north and west of the mainland. Following the unification of Norway, they had become the Norwegian Kingdom of the Isles, locally controlled by Godred Crovan, and known by Norway as Suðreyjar (Old Norse, traditionally anglicised as Sodor), meaning southern isles. The former territory of Dal Riata acquired the geographic description Argyle (now Argyll): the Gaelic coast.

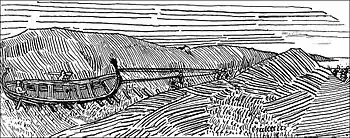

In 1093, Magnus, the Norwegian king, launched a military campaign to assert his authority over the isles. Malcolm, the king of Scotland, responded with a written agreement, accepting that Magnus' had sovereign authority of over all the western lands that Magnus could encircle by boat. The unspecific wording led Magnus to have his boat dragged across the narrow isthmus at Tarbert, while he rode within it, so that he would thereby acquire Kintyre, in addition to the more natural islands of Arran and Bute.

Supposedly, Magnus's campaign had been part of a conspiracy against Malcolm, by Donalbain, Malcolm's younger brother. When Malcolm was killed in battle a short time later, Donalbain invaded, seized the Scottish kingdom, and displaced Malcolm's sons from the throne; on becoming king, Donalbain confirmed Magnus' gains. Donalbain's apparent keenness to do this, however, weakened his support among the nobility, and Malcolm's son, Duncan, was able to depose him.

A few years later, following a rebellion against Magnus' authority in the Isles, he launched another, fiercer, expedition to re-assert his authority. Many of the rebels, and their forces, sought refuge; they chose to flee to Kintyre and Knapdale. In 1098, being aware of Magnus' ferocity, the new Scottish king, Edgar (another son of Malcolm), quitclaimed to Magnus all sovereign authority over the isles, and the whole Kintyre peninsula - including Knapdale.

In the Isles

In the mid 12th century, Somerled, the husband of Godred Crovan's granddaughter, led a successful coup, and seized the kingship of the Isles.

During the later part of this century, Knapdale was evidently possessed by Suibhne, eponym of both Castle Sween and the MacSweens. In 1262, following increasing hostility between Norway and Scotland, the Scots forced Suibhne's heir, Dubhghall, to give up his lands - including Knapdale - to Walter Stewart, Earl of Menteith. In 1263, Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway launched an invasion of Scotland to reassert Norwegian sovereignty. One of his supporters was Murchadh Mac Suibhne, who was rewarded with the Isle of Arran for his services. Nevertheless, following Hákon's death later that year, Magnús Hákonarson, King of Norway ceded the Suðreyjar to Alexander III, King of Scotland, by way of the Treaty of Perth, in return for a very large sum of money.

Early Scottish Knapdale

.jpg.webp)

By the 13th century, Somerled's descendants had formed into three main families: the MacDougalls, MacRorys and the MacDonalds. At the end of the century, a dispute arose over the Scottish kingship between John Balliol and Robert de Bruys; the MacSweens backed John, hoping to recover Knapdale, the MacDougalls also took John's side, while the MacDonalds and MacRory backed de Bruys. When de Bruys defeated John, he declared the MacDougall lands forfeit, and gave them to the MacDonalds; the MacSweens largely became gallowglass mercenaries in Ireland. De Bruys awarded landlordship of the MacSween's former Knapdale lands to Walter's descendants.

The head of the MacDonald family married the heir of the MacRory family, thereby acquiring the remaining share Somerled's realm, and transforming it into the Lordship of the Isles, which lasted for over a century. After 4 years and 3 children, he divorced Amy, and married Margaret, the daughter of Robert II, the Scottish king, who gave him Knapdale as a dowry.

In 1462, however, John, the then Lord of the Isles, plotted with the English king to conquer Scotland; civil war in England delayed the discovery of this for a decade. Upon the discovery, in 1475, there was a call for forfeiture, but a year John calmed the matter, by quitclaiming Ross (Easter, Wester, and Skye), Kintyre, and Knapdale, to Scotland.

As a comital province (medieval Latin:provincia), Knapdale was extended to include the adjacent lands between Loch Awe and Loch Fyne, which had been under MacSween lordship. In shrieval terms, Knapdale was initially served by the Sheriff of Perth; 5 years later, however, it was transferred to Tarbertshire. Gradually, when the Campbells to the east and north grew more powerful, the centre of power shifted towards them, and the sheriff court moved to Inveraray at the extreme northeast of the then Knapdale. Somewhat inevitably, in 1633, shrieval authority was annexed by the sheriff of Argyll.

When the comital powers were abolished by the Heritable Jurisdictions Act, provincial Knapdale ceased to exist, and the term came to exclusively refer to the present district, south of Lochgilphead. In 1899, counties were formally created, on shrieval boundaries, by a Scottish Local Government Act; the district of Knapdale – together with the rest of the former province – therefore became part of the County of Argyll.

Modern times

Knapdale Forest, planted in the 1930s, covers much of the region. During the 1930s, the Ministry of Labour supplied the men from among the unemployed, many coming from the crisis-hit mining and heavy industry communities of the Central Belt. They were housed in one of a number of Instructional Centres created by the Ministry, most of them on Forestry Commission property; by 1938, the Ministry had 38 Instructional Centres across Britain. The camp was used to hold enemy prisoners during the Second World War. The hutted camp in Knapdale was located at Cairnbaan, just south of the Crinan Canal, and a surviving building remains in use as a Forestry and Land Scotland workshop.

Following late 20th century reforms, Knapdale is now within the wider region of Argyll and Bute.

Ownership

Much of Knapdale is in the ownership of Forestry and Land Scotland.[2][3][10] The two largest private estates are located to either side of Loch Caolisport:[11] the Ellary & Lochead Estate covers 11,183 acres (4,526 hectares) on the north side of the loch,[12] whilst the Ormsary covers 19,595 acres (7,930 hectares) on the southern side.[13] Ormsay Estate belongs to Sir William Lithgow,[13] 2nd Baronet of Ormsay and vice-chairman of Scottish shipbuilding company Lithgows.

A 173-acre (70-hectare) estate in the area belongs to former chief executive of Network Rail, Iain Coucher. Nick-named "Iainland", the property was purchased by Coucher in 2010 following his controversial departure from the company, and includes two islands in the Sound of Jura.[14][15]

Historic sites

Local attractions include the Chapel of Keills, which is dedicated to St Cormac and was built in the 1100s. The chapel is home to almost 40 carved stones from the early Christian and Medieval periods, of which the most significant is the eighth century Keills Cross, a free-standing cross similar to those found on Iona.[16] A grave-slab in the chapel has a carving of a clarsach similar to the Queen Mary Harp currently at the Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, one of only three surviving medieval Gaelic harps. West Highland grave slabs from the Argyll area suggest that Knapdale is where this harp originated. Further early Christian and Medieval carved stones can also be found at Kilberry,[17] and at the thirteenth century Kilmory Knap Chapel.[18] Castle Sween, on the shores of Loch Sween, was built in the twelfth century and is one of the oldest castle on the Scottish mainland that can be dated with any certainty.[19]

Environment

Four lochs within Knapdale (Loch nan Torran, Loch Fuar-Bheinne, Dubh Loch and Loch Clachaig) are collectively designated as a Special Protection Area[20] due to their importance for breeding black-throated divers.[21] The sea loch of Loch Sween has been designated as a Nature Conservation Marine Protected Area (NCMPA). The inner loch contains maerl beds and burrowed mud, and supports a colony of volcano worm, whilst the sea bed in the more strongly tidal areas at the mouth of Loch Sween is composed of coarser sediments. The loch is also home to one of Scotland's most important populations of native oyster.[22]

Taynish National Nature Reserve is situated within North Knapdale, lying southwest of the village of Tayvallich on the west side of Loch Sween. The reserve encompasses almost all of the Taynish peninsula, which is around five kilometres (three miles) long and one kilometre (5⁄8 mi) wide.[23] The woodlands at Taynish are often described as a 'temperate rainforest', benefiting from the mild and moist climate brought about by the Gulf Stream. Taynish is owned and managed by NatureScot, and was declared a National Nature Reserve in 1977.[23]

In 2005, the Scottish Government turned down a licence application for unfenced reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver in Knapdale. However, in late 2007 a successful application was made for a release project.[24] The trial was to be run over five years by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, with Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) monitoring the project.[25] The first beavers were released in May 2009,[26] although the initial release into the wild of 11 animals received a setback during the first year with the disappearance of two animals and the unproven allegation of the illegal shooting of a third. The remaining population was increased in 2010 by further releases,[27] and in November 2016, the Scottish Government announced that beavers could remain permanently, and would be given protected status as a native species within Scotland. Beavers will be allowed to extend their range naturally from Knapdale (and, separately, along the River Tay); however to aid this process and improve the health and resilience of the population a further 28 beavers will be released in Knapdale between 2017 and 2020.[28]

Gallery

View from Knapdale towards Jura

View from Knapdale towards Jura Loch Caolisport

Loch Caolisport Forest track in Knapdale

Forest track in Knapdale "Iainland"

"Iainland"

Footnotes

- ↑ Alongside 2,000 ft (609.6 m), this threshold on summit elevation is a widely used criterion for classification as a mountain in the British Isles.

References

- 1 2 3 Scotland's Census, Output Areas North Knapdale and South Knapdale Civil Parishes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ordnance Survey. Landranger 1:50000 Map Sheet 55 (Lochgilphead & Loch Awe)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ordnance Survey. Landranger 1:50000 Map Sheet 62 (North Kintyre & Tarbert)

- ↑ "Knapdale". VisitScotland. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ "National Scenic Areas". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- 1 2 "National Scenic Areas - Maps". SNH. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Route 78 - The Caledonia Way". Sustrans. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "Marilyn Region 19". www.hill-bagging.co.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Census data (1801–1951) after A vision of Britain

- ↑ "Knapdale". Forestry Commission Scotland. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ "Map Search Function". Who Owns Scotland. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ "Property Page - Ellary & Lochead Estate". Who Owns Scotland. 30 September 2002. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Property Page - Ormsary Estate". Who Owns Scotland. 14 August 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ Cohen, Nick (31 January 2010). "It's all aboard the gravy train for Network Rail bosses". Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Silvester, Norman (11 July 2010). "Controversial rail chief splashes out on £1m laird's mansion". Daily Record. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Keills Chapel and Cross, Overview". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Kilberry Sculptured Stones". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Kilmory Knap Chapel". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Castle Sween". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Sitelink - Map Search". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Site Details for Knapdale Lochs". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Loch Sween NCMPA". NatureScot. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- 1 2 "The Story of Taynish National Nature Reserve" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ WATSON, JEREMY (30 September 2007). "Beavers dip a toe in the water for Scots return". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ↑ "UK | Scotland | Glasgow, Lanarkshire and West | Beavers to return after 400 years". BBC News. 25 May 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ "UK | Scotland | Glasgow, Lanarkshire and West | Beavers return after 400-year gap". BBC News. 29 May 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ↑ "New breeding beaver pair released in Scotland". BBC News. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ↑ "Beaver population increased in Knapdale". Scottish Wildlife Trust. 28 November 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

External links

- Knapdale People, the history of modern Knapdale using historic documents.

- - Information on the Knapdale Beaver Trial Introduction.

- - Visitor information for Inveraray, Tarbert, Knapdale, Crinan and Lochgilphead.