Kermac Macmaghan | |

|---|---|

Kermac's name as it appears on folio 121v of AM 45 fol (Codex Frisianus): "Kiarnakr son Makamals".[1] |

Kermac Macmaghan (fl. 1262–1264) was a thirteenth-century Scottish nobleman. In 1262, he is stated to have aided William I, Earl of Ross in a particularly vicious attack in the Hebrides. The assault itself is recorded by a thirteenth-century Scandinavian saga, and was likely conducted on behalf of Alexander III, King of Scotland, who wished to incorporate Isles into the Scottish realm. The following year, Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway launched an expedition into the Isles to reassert Norwegian authority. The latter's campaign proved to be an utter failure, and after his departure and death the same year, the Scots forced the submission of the leading magnates of the Isles. In 1264, Kermac is recorded to have received compensation for services rendered. A fifteenth-century pedigree concerning Clan Matheson (Clann Mhic Mhathain) seems to indicate that Kermac is identical to a certain Coinneach mac Mathghamhna, ancestor of the clan. The latter may or may not be an ancestor of Clan Mackenzie (Clann Choinnich).

Scottish vassal

.png.webp)

In the midpoint of the thirteenth century, Alexander II, King of Scots, and his son and successor, Alexander III, King of Scots, made several attempts to incorporate the Hebrides into the Scottish realm.[2] Forming a part of the Kingdom of the Isles, these islands were a component of the far-flung Norwegian commonwealth.[3] The independence of the Islesmen, and the lurking threat of their nominal overlord, the formidable Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway, constituted a constant source of concern for the Scottish Crown.[2]

.png.webp)

In 1261, Alexander III sent an embassy to Norway attempting to negotiate the purchase of the Isles from the Norwegian Crown. When mediation came to nought, Alexander III evidently orchestrated an invasion into the Isles as means to openly challenge his Norwegian counterpart's authority.[4] Specifically, the thirteenth-century Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar indicates that Kermac aided William I, Earl of Ross during this action, and states that the two led a force of Scots who burnt down a town and churches on Skye. The invaders are described to have killed many men and women in their attack, and to have viciously impaled little children upon their spears.[5] It is possible that the remarkable savagery attributed to the Scots may have been intended to terrorise the Islesmen into submission.[6] The island itself appears to have formed part of the kingdom controlled by Magnús Óláfsson, King of Mann and the Isles.[7] The earl's followers in this enterprise were likely drawn from his vast provincial lordship.[8]

Thus provoked, Hákon assembled an enormous fleet to reassert Norwegian sovereignty along the north and west coasts of Scotland. In July 1263, this fleet disembarked from Norway, and by mid August, Hákon reaffirmed his overlordship in Shetland and Orkney, forced the submission of Caithness, and arrived in the Hebrides.[10] Having rendezvoused with his vassals in the region, Hákon secured several castles, oversaw raids into the surrounding mainland.[11] Unfortunately for the Norwegian king, stormy weather drove some of his ships ashore on the Ayrshire coast. A series of inconclusive skirmishes upon the shore near Largs, together with ever-worsening weather, discouraged the Norwegians and convinced them to turn for home. After redistributing portions of the region to certain faithful supporters, Hákon led his forces from the Hebrides and reached the Northern Isles, where he fell ill and died that December.[12]

Although Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar declares that the Norwegian campaign was a triumph, in reality it was an utter failure.[19] Hákon had failed to break Scottish power; and the following year, Alexander III seized the initiative, and oversaw a series of invasions into the Isles and northern Scotland. According to the thirteenth-century Gesta Annalia I, one such expedition was undertaken by Alexander Comyn, Earl of Buchan, William, Earl of Mar, and Alan Hostarius.[20] Heavy fines were extracted from the northern reaches of the Scottish realm. Two hundred head of cattle were extracted from the Caithnessmen,[21] and one hundred eighty head of cattle from the Earl of Ross himself.[22] The severity of this latter fine could be evidence that the earl's actions during the Scoto-Norwegian conflict were deemed unacceptable by the Scottish Crown.[23] In fact, the aforesaid Alexander Comyn and Alan are known to have extracted twenty head of cattle from William's earldom and granted this sum to Kermac as compensation for services rendered.[24][note 2]

In 1266, almost three years after Hákon's abortive campaign, terms of peace were finally agreed upon between the Scottish and Norwegian Crowns. Specifically, with the conclusion of the Treaty of Perth in July, Hákon's son and successor, Magnús Hákonarson, King of Norway, formally resigned all rights to Mann and the islands on the western coast of Scotland. In so doing, the territorial dispute over Scotland's western maritime region was settled at last.[26]

Ancestral figure

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_967612.jpg.webp)

Kermac appears to be identical to Coinneach mac Mathghamhna, a figure who appears in the pedigree of Clan Matheson (Clann Mhic Mhathain) preserved within the fifteenth-century MS 1467.[30] If correct, Kermac would be the clan's eponymous ancestor,[31] and the record of 1264 would be the earliest recorded instance of the Gaelic surname borne by the clan.[32][note 3] Another clan covered within MS 1467 is the neighbouring Clan Mackenzie (Clann Choinnich).[34] Although this Mackenzie genealogy can be interpreted as evidence of a line of descent from Coinneach as well,[35] an alternative interpretation of this source is that it is evidence that the clans share an earlier common ancestor.[36][note 4]

According to tradition that seems to refer to Coinneach, a young chieftain from Kintail—a man related to the Mathesons—spent time on the Continent in the service of the King of France. After having travelled to distant lands on a ship provided by the king, this chieftain is said to have returned home to Scotland a prosperous and accomplished man, and was later commissioned by Alexander II, King of Scotland to construct Eilean Donan Castle.[27] According to the mediaeval chronicler Matthew Paris, Hugh de Châtillon, Count of Saint-Pol commissioned the construction of a great ship at Inverness in preparation for the Seventh Crusade.[41] Although it is unknown whether Kermac was indeed a sea-going participant in this crusade led by Louis IX, King of France,[42] some Scottish noblemen certainly did accompany the king on the campaign.[43]

Notes

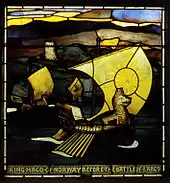

- ↑ The painting depicts Colin Fitzgerald bravely saving Alexander III from a stag. The painting was likely commissioned by the Mackenzie chief, Francis Humberstone Mackenzie, as a means to rehabilitate his family's standing in society.[14] Although the Mackenzies possessed Jacobite affiliations earlier in the century, the painting incorporates elements from contemporary military uniforms and weaponry, seemingly as a means to stress his family's loyalty to the reigning George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland.[15] The heroically-depicted Colin may have been a genealogical invention of George Mackenzie, Earl of Cromartie,[16] although there is evidence to suggest a Fitzgerald origin of the clan was claimed somewhat earlier in the seventeenth century.[17] The history of the Mackenzies cannot be securely traced before the fifteenth century. Surviving manuscript histories of the clan date to the seventeenth century, and much of the information preserved by these sources is unreliable in terms of the clan's early history. For instance, these histories assert that the Mackenzies descend from Colin, an otherwise unattested nobleman from Ireland who supposedly lived during the reign of Alexander III and fought for the king at Largs. The absence of names equating to Colin and Fitzgerald from the MS 1467, and the lack of contemporary evidence noting such a man, strongly suggest that this Fitzgerald origin of the Mackenzies is an unhistorical genealogical construction.[18]

- ↑ The record of this particular transaction exists only in a seventeenth-century transcription.[25] Although Kermac's name is preserved as "Kermac Macmaghan" in this copy,[24] it is likely that the first name is actually a miscopy of "Kennac", an otherwise attested form of the Gaelic names Cainnech and Coinneach.[25]

- ↑ The surname Matheson is derived from a patronymic form of a short form of Matthew.[33] A form of the Gaelic surname borne by the clan is Mac Mhathghamhuin. This name came to be anglicised as Matheson on account of the similar sound of these names.[32] The names (Mac Mhathghamhuin and Matthew) are otherwise unrelated.

- ↑ Although there is reason to suspect that the ancestry of the Mackenzies and Mathesons links up at some point, it is not certain where this connection lies.[37] If the Mackenzie pedigree is taken literally, the clan's descent is traced from a certain Gille Eoin na hAirde.[38] The Matheson pedigree traces a line of descent from Coinneach's grandfather, a certain Cristin.[39] If a garbled pedigree preserved by the eighteenth-century Black Book of Clanranald is taken into account—a source that accords a son to Gille Eoin named Cristin—it could be reveal that the Cristin of the Matheson pedigree was a son of Gille Eoin na hAirde. If correct, the genealogical connection between the two clans would seem to date generations before Coinneach.[40] On the other hand, there is reason to suspect that the number of generations outlined in the Mackenzie pedigree may be inaccurate. If taken into account, this pedigree could instead indicate that the genealogical link between the clans exists in the person of Coinneach's son, Murchadh.[31]

Citations

- ↑ Unger (1871) p. 569; AM 45 Fol (n.d.).

- 1 2 Oram (2011) chs. 13–14; Reid (2011).

- ↑ Beuermann (2010); Brown (2004) p. 68.

- ↑ Crawford (2013); Wærdahl (2011) p. 49; Brown (2004) p. 56; McDonald (2003a) p. 43; Alexander; Neighbour; Oram (2002) p. 18; McDonald (1997) pp. 105–106; Cowan (1990) pp. 117–118; Crawford or Hall (1971) p. 106; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 212.

- ↑ Cochran-Yu (2015) pp. 46–47; Munro; Munro (2008); Barrow (2006) p. 146; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 256; McDonald (2003b) pp. 56, 132; McDonald (1997) p. 106; Cowan (1990) pp. 117–118, 130 n. 70; Crawford or Hall (1971) p. 106; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 212; Matheson (1950) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 605; Dasent (1894) pp. 339–340; Vigfusson (1887) p. 327; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 217.

- ↑ Alexander; Neighbour; Oram (2002) p. 18.

- ↑ Crawford (2013).

- ↑ Brown (2004) p. 56.

- ↑ Caldwell (1998) p. 28.

- ↑ Alexander; Neighbour; Oram (2002) p. 18; McDonald (1997) pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 257–258.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 258–261.

- ↑ Alexander III of Scotland Rescued (2005).

- ↑ McKichan (2014) p. 54; Macleod (2013) ch. 4.

- ↑ Macleod (2013) ch. 4.

- ↑ Sellar, WDH (1997–1998); Matheson (1950).

- ↑ MacGregor (2002) pp. 234 n. 125, 221, 237 n. 185.

- ↑ McKichan (2014) pp. 51–52; MacCoinnich (2003) pp. 176–179.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 260–261; McDonald (1997) p. 115; Cowan (1990) pp. 122–123.

- ↑ McDonald (1997) pp. 115–116; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 213–214; Skene (1872) p. 296; Skene (1871) p. 301.

- ↑ Carpenter (2013) p. 157 § 12; Crawford (2013); Crawford (2004) p. 38; Duncan (1996) p. 581; Crawford or Hall (1971) p. 109; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 214; Fraser-Mackintosh (1875) p. 34; Thomson (1836) p. *31.

- ↑ Carpenter (2013) p. 157 § 13; McDonald (2003a) p. 44 n. 81; Duncan (1996) p. 581; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 214; Thomson (1836) p. 32*.

- ↑ McDonald (2003a) p. 44 n. 81.

- 1 2 Carpenter (2013) p. 157 § 13; Barrow (2006) p. 146; Grant (2000) pp. 112, 112 n. 18, 113; McDonald (1997) p. 106 n. 11; Cowan (1990) p. 130 n. 70; Black (1971) p. 587; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 212 n. 5; Matheson (1950) pp. 196–197; Fraser-Mackintosh (1875) p. 38; Thomson (1836) p. 31*.

- 1 2 Matheson (1950) p. 225 n. 12.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 263; McDonald (1997) pp. 119–121.

- 1 2 Miket; Roberts (2007) pp. 84–87; Macquarrie, AD (1982) pp. 129–130; Matheson (1950) p. 221; Macrae (1910) pp. 293–295.

- ↑ Archaeological Survey (2008) p. 1.

- ↑ Archaeological Survey (2008) p. 12; Miket; Roberts (2007) pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Black (1971) p. 587; Matheson (1950); Skene (1890) pp. 485–486, 486 n. 52; Black; Black (n.d.b).

- 1 2 Matheson (1950).

- 1 2 Black (1971) p. 587.

- ↑ Hanks (2006).

- ↑ Sellar, D (1981); Matheson (1950); Black; Black (n.d.a).

- ↑ McDonald (1997) p. 106 n. 11; Cowan (1990) p. 130 n. 70; Sellar, D (1981) p. 111; Matheson (1950).

- ↑ Sellar, D (1981) pp. 110–111, 114 tab. b.

- ↑ Sellar, D (1981) p. 110.

- ↑ Skene (1890) p. 485; Black; Black (n.d.a).

- ↑ Skene (1890) pp. 485–486; Black; Black (n.d.b).

- ↑ Sellar, D (1981) pp. 110–113, 114 tab. b; Macbain; Kennedy (1894) p. 300.

- ↑ Duncan (1996) p. 478; Macquarrie, AD (1982) pp. 129–130; Jordan (1979) p. 70; Matheson (1950) pp. 222–223; Luard (1880) p. 93; Giles (1853) p. 323.

- ↑ Matheson (1950) p. 223.

- ↑ Macquarrie, A (2001); Matheson (1950) p. 223.

References

Primary sources

- "AM 45 Fol". Handrit.is. n.d. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 2. London: Oliver and Boyd.

- Black, R; Black, M (n.d.a). "Kindred 11 MacKenzie". 1467 Manuscript. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Black, R; Black, M (n.d.b). "Kindred 12 Matheson". 1467 Manuscript. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- Carpenter, D (2013). "Scottish Royal Government in the Thirteenth Century From an English Perspective". In Hammond, M (ed.). New Perspectives on Medieval Scotland, 1093–1286. Studies in Celtic History. The Boydell Press. pp. 117–160. ISBN 978-1-84383-853-1. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Dasent, GW, ed. (1894). Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of the Northmen on the British Isles. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 4. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Flateyjarbok: En Samling af Norske Konge-Sagaer med Indskudte Mindre Fortællinger om Begivenheder i og Udenfor Norse Same Annaler. Vol. 3. Oslo: P.T. Mallings Forlagsboghandel. 1868. OL 23388689M.

- Fraser-Mackintosh, C (1875). Invernessiana: Contributions Toward a History of the Town & Parish of Inverness. Inverness: Messrs Forsyth.

- Giles, JA, ed. (1853). Matthew Paris's English History. Bohn's Antiquarian Library. Vol. 2. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Luard, HR, ed. (1880). Matthæi Parisiensis, Monachi Sancti Albani, Chronica Majora. Vol. 5. London: Longman & Co.

- Macbain, A; Kennedy, J, eds. (1894). Reliquiæ Celticæ: Texts, Papers and Studies in Gaelic Literature and Philology, Left by the Late Rev. Alexander Cameron, LL.D. Vol. 2. Inverness: The Northern Counties Newspaper and Printing and Publishing Company. OL 24821349M.

- Macrae, A (1910). History of the Clan Macrae With Genealogies. Dingwall: George Souter. OL 23304367M.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1871). Johannis de Fordun Chronica Gentis Scotorum. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871486M.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1872). John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871442M.

- Skene, WF (1890). Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: David Douglas.

- Thomson, T, ed. (1836), The Accounts of the Great Chamberlains of Scotland, vol. 1, Edinburgh

- Unger, CR, ed. (1871). Codex Frisianus: En Samling Af Norske Konge-Sagaer. Norske historiske kildeskriftfonds skrifter ;9. Oslo: P.T. Mallings Forlagsboghandel. hdl:2027/hvd.32044084740760.

- Vigfusson, G, ed. (1887). Icelandic Sagas and Other Historical Documents Relating to the Settlements and Descents of the Northmen on the British Isles. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 2. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Secondary sources

- "Alexander III of Scotland Rescued from the Fury of a Stag by the Intrepidity of Colin Fitzgerald ('The Death of the Stag')". National Galleries of Scotland. n.d. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Alexander, D; Neighbour, T; Oram, R (2002). "Glorious Victory? The Battle of Largs, 2 October 1263". History Scotland. 2 (2): 17–22.

- Archaeological Survey: Eilean Donan Castles, Ross-shire (PDF). Field Archaeology Specialists. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Barrow, GWS (2006). "Skye From Somerled to A.D. 1500" (PDF). In Kruse, A; Ross, A (eds.). Barra and Skye: Two Hebridean Perspectives. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 140–154. ISBN 0-9535226-3-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Beuermann, I (2010). "'Norgesveldet?' South of Cape Wrath? Political Views Facts, and Questions". In Imsen, S (ed.). The Norwegian Domination and the Norse World c. 1100–c. 1400. Trondheim Studies in History. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press. pp. 99–123. ISBN 978-82-519-2563-1.

- Black, GF (1971) [1946]. The Surnames of Scotland: Their Origin, Meaning, and History. New York: The New York Public Library. ISBN 0-87104-172-3. OL 8346130M.

- Brown, M (2004). The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1237-8.

- Caldwell, DH (1998). Scotland's Wars and Warriors: Winning Against the Odds. Discovering Historic Scotland. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-495786-X.

- Cochran-Yu, DK (2015). A Keystone of Contention: The Earldom of Ross, 1215–1517 (PhD thesis). University of Glasgow.

- Cowan, EJ (1990). "Norwegian Sunset — Scottish Dawn: Hakon IV and Alexander III". In Reid, NH (ed.). Scotland in the Reign of Alexander III, 1249–1286. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. pp. 103–131. ISBN 0-85976-218-1.

- Crawford, BE (2004) [1985]. "The Earldom of Caithness and Kingdom of Scotland, 1150–1266". In Stringer, KJ (ed.). Essays on the Nobility of Medieval Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 25–43. ISBN 1-904607-45-4. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Crawford, BE (2013). The Northern Earldoms: Orkney and Caithness From 870 to 1470. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-0-85790-618-2.

- Crawford or Hall, BE (1971). The Earls of Orkney-Caithness and Their Relations With Norway and Scotland, 1158–1470 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/2723.

- Duncan, AAM (1996) [1975]. Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom. The Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 0-901824-83-6.

- Duncan, AAM; Brown, AL (1956–1957). "Argyll and the Isles in the Earlier Middle Ages" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 90: 192–220. doi:10.9750/PSAS.090.192.220. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564. S2CID 189977430.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Grant, A (2000). "The Province of Ross and the Kingdom of Alba". In Cowan, EJ; McDonald, RA (eds.). Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 88–126. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Jordan, WC (1979). Louis IX and the Challenge of the Crusade: A Study of Rulership. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- MacCoinnich, A (2003). "'Kingis rabellis' to 'Cuidich 'n' Rìgh'? Clann Choinnich: The Emergence of a kindred, c.1475–c.1514". In Boardman, S; Ross, A (eds.). The Exercise of Power in Medieval Scotland, 1200–1500. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 175–200. ISBN 1851827498.

- MacGregor, M (2002). "The Genealogical Histories of Gaelic Scotland". In Fox, A; Woolf, D (eds.). The Spoken Word: Oral Culture in Britain, 1500–1850. Politics, Culture and Society in Early Modern Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 196–239. ISBN 0-7190-5746-9.

- Macleod, A (2013) [2012]. From An Antique Land: Visual Representations of the Highlands and Islands, 1700-1880. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-907909-07-8.

- Macquarrie, A (2001). "Crusades". In Lynch, M (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford Companions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Macquarrie, AD (1982). The Impact of the Crusading Movement in Scotland, 1095–c.1560 (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/6849.

- Matheson, W (1950). "Traditions of the MacKenzies". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 39–40: 193–228.

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, RA (2003a). "Old and New in the Far North: Ferchar Maccintsacairt and the Early Earls of Ross, c.1200–1274". In Boardman, S; Ross, A (eds.). The Exercise of Power in Medieval Scotland, 1200–1500. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 23–45.

- McDonald, RA (2003b). Outlaws of Medieval Scotland: Challenges to the Canmore Kings, 1058–1266. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 9781862322363.

- McKichan, F (2014). "Lord Seaforth (1754–1815): The Lifestyle of a Highland Proprietor and Clan Chief". Northern Scotland. 5 (1): 50–74. doi:10.3366/nor.2014.0073. eISSN 2042-2717. ISSN 0306-5278.

- Hanks, P, ed. (2006) [2003]. "Matheson". Dictionary of American Family Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195081374. Retrieved 11 March 2016 – via Oxford Reference.

- Miket, R; Roberts, DL (2007). The Mediaeval Castles of Skye and Lochalsh. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Munro, R; Munro, J (2008). "Ross Family (per. c.1215–c.1415)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54308. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Oram, RD (2011) [2001]. The Kings & Queens of Scotland. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7099-3.

- Reid, NH (2011). "Alexander III (1241–1286)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (May 2011 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/323. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Sellar, D (1981). "Highland Family Origins: Pedigree Making and Pedigree Faking". In Maclean, L (ed.). The Middle Ages in the Highlands. Inverness Field Club. pp. 103–116.

- Sellar, WDH (1997–1998). "The Ancestry of the MacLeods Reconsidered". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 60: 233–258.

- Wærdahl, RB (2011). Crozier, A (ed.). The Incorporation and Integration of the King's Tributary Lands into the Norwegian Realm, c. 1195–1397. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20613-7. ISSN 1569-1462.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)