Keizō Hayashi | |

|---|---|

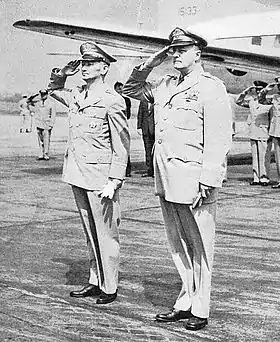

.jpg.webp) General Hayashi as Chairman of the Joint Staff Council in 1954 | |

| Native name | 林 敬三 |

| Born | 8 January 1907 Ishikawa, Japan |

| Died | 12 November 1991 (aged 84) Tokyo, Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | National Police Reserve National Safety Force |

| Years of service | 1950–1964 |

| Rank | |

| Awards | |

Keizō Hayashi (林 敬三, Hayashi Keizō, 8 January 1907 – 12 November 1991) was a Japanese civil servant, general officer and the first Chairman of Joint Staff Council (JSC), a post equivalent to Chief of the General Staff in other countries, from 1954 to 1964. He was instrumental in founding the post-war Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) in 1954.

Hayashi began his civil service career in the Home Ministry in 1929. In post-war Japan, he became Governor of Tottori Prefecture from 1945 to 1947 and Director of the Bureau of Local Affairs from 1947 until the Home Ministry was disbanded in the same year. After that, he was appointed Vice-Minister of Imperial Household from 1948 to 1950, during which he became a confidant of Emperor Showa.

After the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Hayashi, who did not have prewar military background, was chosen by Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, with the endorsement of the American occupation authority, to head the newly formed National Police Reserve (NPR) in the capacity as Superintendent-General. Since Japan had been demilitarized after the Second World War, one of his major tasks was to build up the NPR as the foundation of Japan's self-defense power in post-war era. He was also responsible for developing a new mind-set for the NPR so as to adapt to post-war changes. When the NPR was restructured as the National Safety Force (NSF) in 1952, he was appointed Chief of the 1st (Ground) Staff of the First Staff Office, which was the top decision making body of the NSF.

Hayashi helped found the JSC and the JSDF after Japan regained its status as a sovereign state under the Treaty of San Francisco in 1954. As Chairman of JSC, he assisted the Director-General of Defense Agency (JDA) in formulating defense plans, reviewing proposals as submitted by the JSDF, carrying out defense-related intelligence and investigation work, as well as fostering closer military ties with the United States and its allies. Having served in the JSC for ten years, he was not only the longest-serving Chairman, but was also the only Chairman with civilian civil service background. In retirement, he took an active part in public affairs, serving as, among others, President of the Japan Housing Corporation from 1965 to 1971, of the Japanese Red Cross from 1978 to 1987, and of the Japan Good Deeds Association from 1983 to 1990.

Biography

Early years

Keizō Hayashi was born on 8 January 1907 in Ishikawa Prefecture in the Chūbu region of Japan, with family's koseki registered in Tokyo Prefecture.[1][2] He was the eldest son of Lieutenant-General Yasakichi Hayashi (1876-1948) of the Imperial Japanese Army and Teruko Hayashi (née Ishikawa).[3][4][1] He had an older sister, Sakurako (born 1903), who was the wife of Kyoshiro Ando (1893-1982), former Governor of Kyoto Prefecture, and two younger sisters, Shigeko (born 1910) and Misako (born 1918).[5][6][7] Instead of joining the army like his father, he studied law in Tokyo Imperial University.[2] He passed the Higher Civil Service Examinations in 1928 and graduated from the law school of the University with a Bachelor of Arts degree the following year.[8][9]

Civil service career

Upon graduation, Hayashi entered the Home Ministry and was posted to the Toyama Prefectural Office as a junior civilian official in 1929.[2] He was promoted to head of the Social Welfare Section of Kyoto Prefecture in 1932 and of Kanagawa Prefecture in 1935.[10] After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, he was posted to the Cabinet Planning Board in March 1941 and he became chief of Section One under Division One of the Board in 1942.[11] In 1943, he was additionally appointed staff officer of the Cabinet and of the Cabinet Legislation Bureau.[10][8] At the later stage of the war, he held a number of offices in 1944 successively, including inspector of the Home Ministry, as well as head of the General Affairs Section and of the Administration Section under the Bureau of Local Affairs of the Home Ministry.[10][12]

In 1945, Hayashi was appointed personal secretary to the Minister of Home Affairs as well as head of the Personnel Section of the Ministry.[13] Shortly after the unconditional surrender of Japan to the Allied Powers in August 1945, he was chosen as Governor of Tottori Prefecture at the age of 38, assuming the office on 27 October, thus becoming the youngest local chief in the history of the Prefecture.[2][14] However, his tenure was cut short in February 1947 when he became Director of the Bureau of Local Affairs.[15] It was the last post he held in the Home Ministry, which was disbanded by the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Allied Powers in December 1947. As a transitional arrangement decided in a Cabinet meeting, he was appointed Director of the temporarily established Office of Domestic Affairs in January 1948.[16] The Office was in existence for around 90 days only, during which he was responsible for overseeing the law enforcement services formerly managed by the now-defunct Home Ministry, until the Office was replaced by the National Public Safety Commission.[17]

While the Japanese constitution was being redrafted and the Japanese war criminals were under trial, there were a number of unusual senior staff changes in the Imperial Household Office (to be restructured as the Imperial Household Agency in 1949) between June and August 1948. In particular, two key imperial household officials in the early post-war period, Ōgane Masujirō, the Grand Chamberlain, and Susumu Katō, Vice-Minister of Imperial Household, relinquished their offices.[18] In the reshuffle, Hayashi succeeded Katō on 2 August 1948. By the time when he left the post in 1950,[19] he had become a confidant of Emperor Showa, making him one of the few people who had the privilege to see and talk to the Emperor.[20][21]

National Police Reserve

After the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, there was a vacuum of defense in Japan as the United States (US) redeployed much of its troops from Japan to the Korean Peninsula. Against this background, the GHQ started to formulate plans to allow Japan rearm itself by setting up the National Police Reserve (NPR) as the foundation of post-war Japan's self-defense power.[22][23] As a policy endorsed by the United Nations (UN) and the American occupation authority, the backbone of the NPR had to be formed by civilian officials and police officers from the ex-Home Ministry, while prewar Japanese military officials were barred from joining the NPR.[24][25][26] Although the policy was supported by Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida and Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur,[27] it was met with some opposition from within the GHQ. For example, Major-General Charles A. Willoughby, Chief of Intelligence (G-2) on General MacArthur's staff, attempted to recommend Takushiro Hattori, the former head of Operations Section of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office, to command the NPR, a recommendation which was strongly opposed by Yoshida.[28] Another prewar Japanese military officer, Eiichi Tatsumi, however, turned down the same offer even though he was a military adviser to Yoshida, who viewed him as an acceptable choice.[29]

In early September 1950, Yoshida nominated Hayashi to head the NPR with support from Emperor Hirohito, who not only had confidence in Hayashi, but also appreciated his performance as Vice-Minister of Imperial Household.[21][20] This time the nomination of Hayashi was opposed by Willoughby and his intelligence staff, which was responsible for recruitment matters of NPR. They not only favored Hattori and other prewar Japanese army officers, but also even tried to prevent Hayashi from getting appointed.[30] Nevertheless, their views were not shared by other parties within the GHQ. In particular, both Brigadier-General Courtney Whitney, Chief of the Government Section (GS), which was responsible for the NPR's personnel matters, and Major General Whitfield P. Shepard, Chief of the Civil Affairs Section Annex (CASA), which was responsible for the development and training of the NPR, favored Hayashi.[30][22] Operations Section (G-3) of the GHQ, which dealt with military operations, law enforcement and repatriation, also showed their support to Hayashi.[31] Because of Willoughby's opposition, the nomination of Hayashi dragged on for a month and it took a few more weeks before the nomination was approved only after the intervention of MacArthur and Yoshida.[32][33][27]

On 9 October 1950, Hayashi was appointed to head the NPR. Formal appointment as Superintendent-General was made on 23 October.[34][35] Later on 29 December, the headquarters of the NPR was restructured as the General Group Headquarters.[36][37] Apart from him, some 160 key officials of the NPR were appointed. While most of the key posts, such as Deputy Superintendent-General and commanders of the Regional Units were filled by civilian officials and police officers from the ex-Home Ministry,[35][36] the influence of those prewar army officers and other right-wing figures, who called Hayashi a "home affairs warlord" (as against the "Showa warlords"), was greatly diminished in the NPR and its successor, the National Safety Force (NSF, predecessor of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force).[2]

Hayashi's first task as the Superintendent-General was to lay down a new mind-set for the NPR, since the "spiritual training" (seishin kyoiku) in the prewar Imperial Japanese Army had been scrapped.[38][39] As the post-war forces were no longer be required to pledge absolute allegiance to the Emperor under the post-war "Peace Constitution",[40] the senior management of the NPR was deeply anxious about the lack of a new and appropriate mind-set.[41] Hayashi attempted to explore one by striking a balance between old and new concepts.[42] The new mind-set was finally introduced in a speech he made in March 1951, in which he emphasized, "The fundamental spirit of the NPR I firmly hold [is] patriotism and love of our race". He pointed out that the NPR was loyal to the country and the people, instead of the Emperor.[43][41][44] In another speech to the officers of the NPR, he said, "Needless to say, if this organization is to play its rightful role in the new Japan, it must be 'an organization of the people.' This must be the fundamental principle upon which this defense force should be established"[43] By formulating the new mind-set, he connected the new post-war defense force with the people and cut-off its lineage with the prewar Japanese armed forces.[43][45][46][47]

On 28 April 1952, Japan regained its status as a sovereign state under the Treaty of San Francisco. One of the first agendas of Yoshida and his Cabinet was to establish the National Safety Agency (predecessor of the Defense Agency) to oversee both the NPR and the Coastal Safety Force (predecessor of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force). Hayashi and Keikichi Masuhara, Director-General of the NPR, supported the idea to put ground and maritime forces under the supervision of a unified body so as to avoid a recurrence of interservice rivalry during the Second World War. However, the Coastal Safety Force opposed the plan as they feared that they would be marginalized by the NPR, which was larger in scale.[48] At last, Hayashi and Masuhara won the day and the National Safety Agency was formally established on 1 August.[49]

To tie-in with the establishment of the National Safety Agency, the NPR was restructured as the NSF, with Hayashi becoming Chief of the 1st (Ground) Staff (later became known as Chief of Staff, Ground Self-Defense Force) to head the First Staff Office, which was the top decision making body of the NSF.[50] In September 1952, he was appointed to a newly formed high-level planning committee in the capacity of Chief of the 1st Staff. Other members of the committee included Chief of the 2nd Staff (later became known as Chief of Staff, Maritime Self-Defense Force) and other senior officials of the National Safety Agency.[51] The objective of the committee was to formulate long-term military planning for Japan.[51] Besides, units and formations in NSF expanded considerably under the command of Hayashi.[50] New units, such as the Northern Army, were formed, while the National Safety Academy and the NSF Aviation School were both founded in 1952.[50][52]

Chairman of Joint Staff Council

When the Defense Agency (JDA) and the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) were formed on 1 July 1954, the NSF and the Coastal Safety Force were restructured as the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) respectively.[53] The two Forces, together with the newly formed Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF), were the three major components of the JSDF.[53] The Joint Staff Council (JSC) was also formed on top of the three Forces, with Hayashi becoming Chairman of JSC with rank of General, which was equivalent to Chief of the General Staff in other countries.[54][55][56] The JSC served under the Director-General of JDA and Hayashi was responsible for assisting in formulating overall defense plans, supplies plans and training plans, as well as coordinating related plans prepared by the Ground, Maritime and Air Staff Offices and operation directives as issued by the JSDF.[57] Also, the JSC was responsible for defense-related intelligence and investigation work under his command.[57]

As Chairman of JSC, Hayashi took part in defense collaboration and exchanges with other countries. Since the Defense Agency attached much importance to the research and development of missiles soon after the founding of JSDF, he met Major-General Gerald D. Higgins, the US Chief of Military Assistance Advisory Group in Japan (MAAG-J), in August 1954, to exchange views on the possibility of sending JSDF personnel to the US to study countermeasures against missile attack.[58] In September 1954, he visited the US under invitation of the US Department of Defense. In Washington, D.C., he met Charles Erwin Wilson, US Secretary of Defense, and Admiral Arthur W. Radford, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, among other top politicians and military officials.[59] They held high-level strategic conferences, discussing issues on deployment of US troops to Japan and Korea, collective military actions, as well as the possibility of providing sufficient jet planes and destroyers to strengthen the power of the JSDF.[60] When Japan and the US conducted their first joint military exercise at theater level in 1956, Hayashi was the chief official representing Japan, while his US counterpart was Lieutenant-General Arthur Trudeau, Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Operations, Far East and UN Command.[61]

By the end of the 1950s, Japan had already become an important ally in the Western defense system as dominated by the US.[62] To foster closer ties with other allies of the US, Hayashi paid several visits to some of these countries.[56] In particular, he paid a visit to the United Kingdom (UK) under the invitation of the British government from 5 to 16 May 1957, during which he visited the British Armed Forces and their facilities in London and other places.[63] It was the first formal visit of a senior Japanese general officer to the UK since 1937, when Lieutenant-General Masaharu Homma attended the coronation ceremony of King George VI.[64] After visiting the UK, Hayashi arrived at Bonn, West Germany on 21 May 1957. On the following day, he met Franz Josef Strauss, Federal Minister of Defense, and Generalleutnant Adolf Heusinger, Inspector General of the Bundeswehr.[65][66] It was the first post-war meeting between military chiefs of Japan and Germany and they achieved productive agreements on building a military exchange mechanism.[67] On 14 and 15 November 1959, Hayashi attended a multinational military conference as hosted by Admiral Harry D. Felt, Commander of the US Pacific Command, at Baguio, the Philippines.[68][69] During his stay, he met Lieutenant-General Manuel F. Cabal, Chief of Staff of the Philippines, General Peng Meng-chi, Chief of the General Staff of the Republic of China, as well as other military chiefs from member states of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization with a view to fostering stronger military ties with countries in the Western Pacific Region.[68][70][69]

Although Hayashi was the head of JSDF in the capacity of Chairman of JSC, he had limited powers to assume command in joint operations as the JSC itself was no more than a consultative body.[71] It was not changed until 1961, when the functions of the JSC were modified and the Chairman was empowered to give orders to the JSDF when there was an operation. The Chairman was also given greater command authority in joint operations with greater powers to execute orders from the Director-General of JDA.[72][73] Hayashi retired from the JSC in August 1964 after ten years of service.[37][74] He was not only the longest-serving Chairman, but was also the only Chairman with civilian civil service background. All of his successors were career military officers and their tenure was confined to around one to three years only.[75][76]

Later years

After retiring from the JSC and the JSDF with rank of General in 1964, Hayashi took an active part in public affairs. He was President of the Japan Housing Corporation from 1 August 1965 to 31 March 1971 and President of the Japan Good Deeds Association from July 1983 to July 1990.[37][77] For some years he was Chairman of the Board of Directors of Jichi Medical University.[37] He was also closely associated with the Japanese Red Cross. He was appointed to the Board of Governors on 1 April 1977 and he became president from 1 April 1978 to 31 March 1987. Later on he became Honorary President.[37]

Besides, Hayashi was appointed to public committees on a few occasions. On 16 March 1981, Prime Minister Zenkō Suzuki and his Cabinet set up the Second Provisional Council for the Promotion of Administrative Reform under the chairmanship of Toshiwo Doko with a view to reforming the financial system and moving forward administrative reform.[78] Hayashi was appointed to the Council in the capacity of President of the Japanese Red Cross alongside other prominent community leaders.[79] They subsequently submitted a reform report to the Prime Minister.[80] On 3 August 1984, he was invited by Takao Fujinami, Chief Cabinet Secretary under Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, to chair a private advisory body on controversies surrounding "official visits by Cabinet ministers to Yasukuni Shrine".[81] In that capacity, he examined the controversies from legal, social and religion aspects with 14 other members as appointed to the private advisory body from the legal, literature and religion circles.[82][81]

Hayashi died in a hospital in Shibuya, Tokyo on 12 November 1991,[83] aged 84.[84] His funeral was held at Zōjō-ji in Shiba Park, Tokyo.[37] He was conferred Senior Third Rank posthumously.[85]

Honors

In recognition of his public services to Japan, Hayashi was bestowed the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure (1st Class) by the Japanese government on 29 April 1977, thus becoming the first recipient with JSDF background.[86] On 3 November 1987, he was further bestowed the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (1st Class).

Besides, when he was Chairman of JSC, he became the first Japanese to be awarded Legion of Merit by the US on 10 November 1958.[87][88] The honor was presented to him by Douglas MacArthur II, US Ambassador to Japan, at the Embassy of the US in Tokyo.[87]

Personal life

Hayashi's wife, Shizue, was born in January 1912.[1] She was the fifth daughter of Hyoji Futagami (1878–1945), Chief Secretary of the Privy Council of Japan.[89][1] The couple had one son and one daughter. Their son, Masaharu, born in 1935, graduated from the University of Tokyo with a major in Economics, and he worked in Sumitomo Metal Industries.[90][1] Their daughter, Mineko, was born in 1942.[8]

Hayashi's hobbies included traveling and reading.[1] He wrote a number of books in Japanese, such as Japan's Defense Problems from International Perspectives (1962),[91] A Guide for the Heart (1960) as included in the "Self-Defense Forces Education Series",[92] Speeches on Local Self-Governance (1949)[93] and Local Self-Governance: Review and Prospect (1976), etc.[94]

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 現代名士家系譜刊行会 1969, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 华丹 2014, p. 24.

- ↑ 読売新聞社 1981, p. 157.

- ↑ 永野節雄 2003, p. 142.

- ↑ 民衆史研究会 1985, p. 183.

- ↑ 秦郁彦 1981, p. 12.

- ↑ 日本官界情報社 1967, p. 315.

- 1 2 3 日本官界情報社 1963, p. 856.

- ↑ 日本官界情報社 1967, p. 833.

- 1 2 3 柴山肇 2002, p. 321.

- ↑ 池田順 1997, p. 364.

- ↑ 大霞会 1987, p. 533.

- ↑ 日本官界情報社 1963, p. 747.

- ↑ 鳥取県 1969, p. 677.

- ↑ Kowalski & Eldridge 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ 大霞会 1977, p. 367.

- ↑ Steiner 1965, p. 77.

- ↑ 茶谷誠一 2014, p. 50.

- ↑ 杉原泰雄 et al. 1998, p. 452.

- 1 2 鬼塚英昭 2010, pp. 231–240.

- 1 2 Kowalski & Eldridge 2014, p. 66.

- 1 2 华丹 2014, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ 赫赤, 关南 & 姜孝若 1988, p. 188.

- ↑ 华丹 2014, p. 25.

- ↑ 中村政则 2008, p. 49.

- ↑ 华丹 2014, pp. 23–25.

- 1 2 Yoshida, Nara & Yoshida 2007, p. 151.

- ↑ 华丹 2014, p. 27.

- ↑ Welfield 2013, pp. 75–76.

- 1 2 Maeda 1995, p. 25.

- ↑ Kowalski & Eldridge 2014, pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Maeda 1995, p. 31.

- ↑ Welfield 2013, p. 76.

- ↑ Kuzuhara 2006, p. 99.

- 1 2 葛原和三 2006, p. 83.

- 1 2 真田尚剛 2010, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Japan Military Review 1992, p. 136.

- ↑ 葛原和三 2006, p. 91.

- ↑ Kowalski & Eldridge 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ 楊森 2001, pp. 34–35, 38.

- 1 2 楊森 2001, p. 40.

- ↑ Kowalski & Eldridge 2014, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 Yoneyama 2014, p. 85.

- ↑ Frühstück 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ 米山多佳志 2014, p. 138.

- ↑ 葛原和三 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Maeda 1995, p. 22.

- ↑ 趙翊達 2008, p. 56.

- ↑ 华丹 2014, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 华丹 2014, p. 30.

- 1 2 趙翊達 2008, p. 58.

- ↑ 赫赤, 关南 & 姜孝若 1988, p. 189.

- 1 2 华丹 2014, p. 54.

- ↑ Welfield 2013, p. 406.

- ↑ 孙维本 1992, p. 812.

- 1 2 郭壽華 1966, p. 64.

- 1 2 防衛研究会 1966, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ 岡田志津枝 2009, pp. 25–29.

- ↑ Hsinhua News Agency 1954, p. 75.

- ↑ Hsinhua News Agency 1954, p. 170.

- ↑ Trudeau 1986, p. 271.

- ↑ Lowe 2010, p. 138.

- ↑ Japan Society of London 1957a, p. 31.

- ↑ Japan Society of London 1957b, p. 11.

- ↑ 新华社 1957, p. 34.

- ↑ The Free Press 1957, p. 12.

- ↑ Prevent World War III 1957, p. 49.

- 1 2 Foreign Broadcast Information Service 1959b, p. AAA 4.

- 1 2 Foreign Broadcast Information Service 1959a, p. BB 9.

- ↑ Foreign Broadcast Information Service 1959c, p. AAA 12.

- ↑ 华丹 2014, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ 防衛省 & 統合 2010.

- ↑ Oriki 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ Auer 1973, p. 279.

- ↑ 小川隆行 2015, p. 109.

- ↑ Auer 1973, p. 117.

- ↑ 日本善行会

- ↑ North 2007, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ 鲁义 1991, pp. 69.

- ↑ North 2007, p. 100.

- 1 2 Safier 1997, p. 57.

- ↑ 国立国会図書館調査及び立法考査局 2007, p. 8.

- ↑ 東京朝刊 1991.

- ↑ 佐藤進 1992, p. 290.

- ↑ 大蔵省印刷局 1991, p. 11.

- ↑ 朝雲新聞社 1977, p. 20.

- 1 2 Tucson Daily Citizen 1958, p. 12.

- ↑ The Free Press 1958, p. 12.

- ↑ 古川隆久 1992, p. 246.

- ↑ 明石岩雄 2007, p. 207.

- ↑ 林敬三 1962.

- ↑ 林敬三 1960.

- ↑ 林敬三 1949.

- ↑ 林敬三 1976.

References

- (in Chinese)楊森 (2001). "從「軍人敕諭」到「自衛隊員倫理法」". 建校五十週年暨第四屆國軍軍事社會科學學術研討會. 國防大學政治作戰學院.

- (in Chinese)趙翊達 (2008). 日本海上自衛隊:國家戰略下之角色. 秀威出版. ISBN 978-9866732911.

- (in Chinese)郭壽華 (1966). 日本通鑑. 中央文物供應社.

- (in Chinese)孙维本 (1992). 中华人民共和国行政管理大辞典. 人民日报出版社.

- (in Chinese)华丹 (2014). 日本自卫队. 陝西人民出版社. ISBN 978-7-224-11012-8.

- (in Chinese)中村政则 (2008). 日本战后史. 张英莉译. 中国人民大学出版社. ISBN 978-7-300-10016-6.

- (in Chinese)赫赤; 关南; 姜孝若 (1988). 战后日本政治. 航空工业出版社. ISBN 7-80046-081-9.

- (in Chinese)新华社 (24 May 1957). "日幕僚长联席会议主席到西德". 新华社新闻稿 (2538期).

- (in Chinese)鲁义 (1991). "战后日本的行政改革及推进措施". 日本研究. 辽宁大学日本研究所 (1991年第2期). ISSN 1003-4048.

- (in Japanese)現代名士家系譜刊行会 (1969). "現代財界家系譜". 第2卷. ASIN B000J9HBTK.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - (in Japanese)読売新聞社 (1981). 「再軍備」の軌跡: 昭和戦後史. ASIN B000J7W6JM.

- (in Japanese)防衛研究会 (1966). 防衛庁・自衛隊. かや書房. ISBN 4-906124-19-4.

- (in Japanese)永野節雄 (2003). 自衛隊はどのようにして生まれたか. 学研. ISBN 4054019889.

- (in Japanese)日本官界情報社 (1963). 日本官界名鑑 第15版. JPNO 51003271.

- (in Japanese)日本官界情報社 (1967). 日本官界名鑑 第19版. JPNO 51003271.

- (in Japanese)大霞会 (1987). 続內務省外史. 地方財務協会.

- (in Japanese)鳥取県 (1969). 鳥取県史 近代第2巻 政治篇. ASIN B000J9HUHI.

- (in Japanese)大霞会 (1977). 內務省外史. 地方財務協会.

- (in Japanese)秦郁彦 (1981). 戦前期日本官僚制の制度・組織・人事. 戦前期官僚制研究会. ISBN 978-4-13-030050-6.

- (in Japanese)柴山肇 (2002). 内務官僚の栄光と破滅. 勉誠出版. ISBN 978-4585050599.

- (in Japanese)池田順 (1997). 日本ファシズム体制史論. 校倉書房. ISBN 978-4751727003.

- (in Japanese)民衆史研究会 (1985). 民衆運動と差別・女性. 雄山閣. ISBN 978-4639005230.

- (in Japanese)東京朝刊 (13 November 1991). "林 敬三氏(日本赤十字社名誉社長、元防衛庁統幕議長)死去". 読売新聞. p. A31.

- (in Japanese)Japan Military Review (1992). "自衛隊「神代」時代の証人逝く". 軍事研究. 27(1)(310) (1月号). ISSN 0533-6716.

- (in Japanese)小川隆行 (2015). "指揮権統一と権限の強化:「統合幕僚監部」の誕生". 完全保存版 自衛隊60年史. 株式会社宝島社 (別冊宝島2377号). ISBN 978-4-8002-4453-6.

- (in Japanese)杉原泰雄; 山内敏弘; 浦田一郎; 渡辺治; 辻村みよ子 (1998). 日本国憲法史年表. 勁草書房. ISBN 4326401885.

- (in Japanese)鬼塚英昭 (2010). 20世紀のファウスト(上巻):黒い貴族がつくる欺瞞の歴史. 成甲書房. ISBN 978-4880862606.

- (in Japanese)佐藤進 (1992). 日本の自治文化: 日本人と地方自治. ぎょうせい. ISBN 978-4324034668.

- (in Japanese)古川隆久 (1992). 昭和戦中期の総合国策機関. 吉川弘文館. ISBN 978-4642036344.

- (in Japanese)朝雲新聞社 (1977), "国防 第26巻", Kokubō, ISSN 0452-2990

- (in Japanese)林敬三 (1949). 地方自治講話. 海口書店. ASIN B000JBJLX2.

- (in Japanese)林敬三 (1960). 心のしおり. 自衛隊教養文庫. 学陽書房. ASIN B000JAQ1H2.

- (in Japanese)林敬三 (1962). 国際的に見た日本の防衛問題. 防衛庁.

- (in Japanese)林敬三 (1976). 地方自治の回顧と展望. 議会職員執務資料シリーズ ; no.199. 佐治村役場.

- (in Japanese)明石岩雄 (2007). 日中戦争についての歴史的考察. 思文閣出版. ISBN 978-4-7842-1347-4.

- (in Japanese)大蔵省印刷局 (20 November 1991). "叙位・叙勲 ○叙位". 官報 第782号.

- (in Japanese)真田尚剛 (2010). "「日本型文民統制」についての一考察:「文官優位システム」と保安庁訓令第9号の観点から" (PDF). 国士舘大学政治研究 第1号. 国士舘大学. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- (in Japanese)茶谷誠一 (2014), 象徴天皇制の成立過程にみる政治葛藤: 1948年の側近首脳更迭問題より (PDF), 成蹊大学文学部学会

- (in Japanese)葛原和三 (2006). "朝鮮戦争と警察予備隊:米極東軍が日本の防衛力形成に及ぼした影響について" (PDF). 防衛研究所紀要. 防衛研究所. 第8巻 (第3号). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015.

- (in Japanese)米山多佳志 (2014). "第2次世界大戦後の韓国・日本の再軍備と在韓・在日米軍事顧問団の活動" (PDF). 防衛研究所紀要. 防衛研究所. 第16巻 (第2号). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2014.

- (in Japanese)防衛省; 統合 (2010), 統合運用について (PDF)

- (in Japanese)岡田志津枝 (2009). "誘導弾導入をめぐる日米の攻防" (PDF). 戦史研究年報. 防衛研究所 (第12号). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2013.

- (in Japanese)国立国会図書館調査及び立法考査局 (2007), 新編 靖国神社問題資料集 (PDF), 国立国会図書館

- Auer, James E. (1973). The postwar rearmament of Japanese maritime forces, 1945-71. Praeger.

- "Daily Report: Foreign Radio Broadcasts". Foreign Broadcast Information Service. No. 227. 20 November 1959a.

- "Daily Report: Foreign Radio Broadcasts". Foreign Broadcast Information Service. No. 229. 24 November 1959b.

- "Daily Report: Foreign Radio Broadcasts". Foreign Broadcast Information Service. No. 230. 25 November 1959c.

- Frühstück, Sabine (2007). Uneasy Warriors: Gender, Memory, and Popular Culture in the Japanese Army. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520247956.

- Hsinhua News Agency (1954). Hsinhua News Agency Release: September.

- Bulletin of the Japan Society of London. No. 22. June 1957a. ISSN 0021-4701.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Bulletin of the Japan Society of London. No. 23. October 1957b. ISSN 0021-4701.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Kowalski, Frank; Eldridge, Robert D. (2014). An Inoffensive Rearmament: The Making of the Postwar Japanese Army. United States Naval Institute. ISBN 978-1591142263.

- Kuzuhara, Kazumi (2006). "The Korean War and The National Police Reserve of Japan: Impact of the US Army's Far East Command on Japan's Defense Capability" (PDF). NIDS Journal of Defense and Security. National Institute for Defense Studies. No. 7. ISSN 1345-4250. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2016.

- Lowe, Peter (2010). "The Cold War and Nationalism in Southeast Asia: British strategy, 1948-60". The International History of East Asia, 1900–1968: Trade, Ideology and the Quest for Order. Edited by Antony Best. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-40124-1.

- Maeda, Tetsuo (1995). The Hidden Army: The Untold Story of Japan's Military Forces. Edition Q. ISBN 9781883695019.

- North, Christopher (2007). The Transition from Technocracy to Aristocracy in Japan, 1955-2003. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58112-305-0.

- Oriki, Ryoichi (2014), The Evolution and the Future of Joint and Combined Operations (PDF), 2014 International Forum on War History, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016

- The Free Press, Reuters, 28 May 1957

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - The Free Press, Reuters, 31 October 1958

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Safier, Joshua (1997). Yasukuni Shrine and the Constraints on the Discourses of Nationalism in Twentieth Century Japan. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 9780965856416.

- "Inside Germany". Prevent World War III. No. 50. Society for the Prevention of World War III. Summer 1957.

- Steiner, Kurt (1965). Local Government in Japan. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804702171.

- Trudeau, Arthur G (1986). Engineer Memoirs: Lieutenant General Arthur G. Trudeau, USA, Retired. United States Government Publishing Office. EP 870-1-26.

- "Foreign Gen. Keizo Hayashi, chief of staff of Japan's self-defense forces, today was awarded the Legion of Merit in the degree of commander by the United States", Tucson Daily Citizen, 10 November 1958

- Welfield, John (2013). An Empire in Eclipse: Japan in the Post-war American Alliance System: A Study in the Interaction of Domestic Politics and Foreign Policy. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1780939957.

- Yoneyama, Takashi (2014). "The Establishment of the ROK Armed Forces and the Japan Self- Defense Forces and the Activities of the U.S. Military Advisory Groups to the ROK and Japan" (PDF). NIDS Journal of Defense and Security. National Institute for Defense Studies. 15. ISSN 2186-6902. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2015.

- Yoshida, Shigeru; Nara, Hiroshi; Yoshida, Kenʼichi (2007). Yoshida Shigeru: Last Meiji Man. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-3932-7.

- 日本善行会, 一般社団法人, 沿革 (in Japanese), archived from the original on 1 September 2015, retrieved 6 July 2015

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)