Juvenilia; or, a Collection of Poems Written between the ages of Twelve and Sixteen by J. H. L. Hunt, Late of the Grammar School of Christ's Hospital, commonly known as Juvenilia, was a collection of poems written by James Henry Leigh Hunt at a young age and published in March 1801. As an unknown author, Hunt's work was not accepted by any professional publishers, and his father Isaac Hunt instead entered into an agreement with the printer James Whiting to have the collection printed privately. The collection had over 800 subscribers, including important academics, politicians and lawyers, and even people from the United States. The critical and public response to Hunt's work was positive; by 1803 the collection had run into four volumes. The Monthly Mirror declared the collection to show "proofs of poetic genius, and literary ability",[1] and Edmund Blunden held that the collection acted as a predictor of Hunt's later success. Hunt himself came to despise the collection as "a heap of imitations, all but absolutely worthless",[2] but critics have argued that without this early success to bolster his confidence Hunt's later career could have been far less successful.

Background

When Hunt was 15, he entered into a series of competitions run by the Monthly Preceptor calling for the submission of both poems and essays. Throughout 1800, Hunt submitted various works including a translation of Horace, which won first prize. In December, he came in second for an essay called "On Humanity to the Brute Creation as a Moral and Christian Duty". The Monthly Preceptor printed many of his poems, even ones not submitted for the competition. The successful publication of these works prompted his father Isaac Hunt to collect his son's childhood poetry to publish them. Since publishers would not pay the expenses to publish a book for an unknown author, Isaac Hunt decided to take subscriptions for the book to defer the cost of publication. Under an agreement with the printer James Whiting, the Hunts collected subscribers with the support of his uncle and aunt, Benjamin and Elizabeth West.[3]

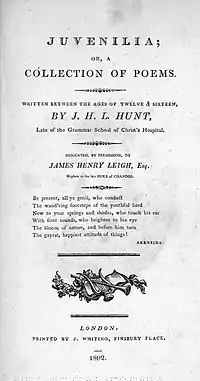

Eventually, they were able to collect over 800 subscribers to the volume. The collection was published March 1801 with the title Juvenilia; or, a Collection of Poems Written between the ages of Twelve and Sixteen by J. H. L. Hunt, Late of the Grammar School of Christ's Hospital with a subscription list that ran for more than 15 pages. The subscribers included important academics and artists, well known publishers and booksellers, and many politicians, lawyers, and government employees. The list covered people from all aspects of British life and even included many from the United States. A frontispiece by Francesco Bartollozi based on a painting by Raphael West was included in the edition based on an allegorical representation of penury from Hunt's poem "Retirement". The third edition included an engraving of Hunt's portrait by Robert Bowyer. By 1803, four editions of the volume had been published with a new set of subscriptions for each, which included many famous politicians, artists, and other well-known individuals.[4]

Poems

The collection separated the poems into sections based on genre and type: elegy, hymn, ode, pastoral, sonnet, allegory modelled after Edmund Spenser's, and a section for miscellaneous. The volume begins with "Macbeth; or, the Ill Effects of Ambition" and "Content". Poems that followed are "Chearfulness" and The Palace of Pleasure. The miscellaneous poems include: "Retirement, or the Golden Mean", "Remembered Friendship", "Christ's Hospital", "The Negro Boy, A Ballad", "Epitaph on Robespierre", "Written at the Time of the War in Switzerland", "Speech of Caractacus to Claudius Caesar", and "Progress of Painting".[5]

In the "Progress of Painting", Hunt reveals his debt to the artistic background of his uncle in introducing the wonders of various painters. Hunt's "Remembered Friendship" is similar to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's depiction of a childhood watching of the sky in Frost at Midnight.[6]

Most of the work was imitative. Although success allowed Hunt greater opportunities and connections in Britain, he later believed that his early success kept him from properly starting his path to become a poet.[7]

Critical response

The response to Hunt's Juvenilia was positive. The reviews focused on Hunt's successful youthful accomplishment and he was well received by the literary establishment.[8] In an immediate review, the Monthly Mirror claimed that the poems were "proofs of poetic genius, and literary ability, which reflect great credit on the youthful author, and will justify the most sanguine expectations of his future reputation".[1] However, Hunt later stated, "I was as proud, perhaps, of the book at the time as I am ashamed of it now [...] a heap of imitations, all but absolutely worthless".[2] Edmund Blunden, in 1930, argued: "The best poetical promise in Juvenilia was an occasional floweriness of colouring and personal fancy [...] But even in most juvenile passages the collection informs us of Hunt's boyish attainments and natural tastes, anticipating his later characteristics in several tendencies."[9]

In 1985, Ann Blainery wrote, "For a boy of 17 it was an achievement, and if it went to his head this was understandable. The shy schoolboy whose poems were despised by his teacher had become a literary lion-cub. Without the confidence imparted by his first book, his career could have been very different."[10] Nicholas Roe claimed, "His Juvenilia has been genuinely impressive for the skill with which he had imitated other writers, and it had deservedly drawn admiration."[11] Anthony Holden argued, "The opening ode on Macbeth [...] is declared, as if by way of apology for its orotund emptiness, to have been written at the age of twelve. Even so, it shows a remarkably precocious technique, as do the marginally more mature teenager's fluent if florid pastiches of Spenser and Pope, Dryden and Gay, Thomson and Johnson, even Akenside and Ossian".[12]

Notes

References

- Blainey, Ann. Immortal Boy. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1985.

- Blunden, Edmund. Leigh Hunt and His Circle. London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1930.

- Edgecombe, Rodney. Leigh Hunt and the Poetry of Fancy. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

- Holden, Anthony. The Wit in the Dungeon. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2005.

- Roe, Nicholas. Fiery Heart. London: Pimlico, 2005.