The Jubilee coinage or Jubilee head coinage are British coins with an obverse featuring a depiction of Queen Victoria by Joseph Edgar Boehm. The design was placed on the silver and gold circulating coinage beginning in 1887, and on the Maundy coinage beginning in 1888. The depiction of Victoria wearing a crown that was seen as too small was widely mocked, and was replaced in 1893. The series saw the entire issuance of the double florin (1887–1890) and, in 1888, the last issue for circulation of the groat, or fourpence piece, although it was intended for use in British Guiana. No bronze coins (the penny and its fractions) were struck with the Jubilee design.

In 1879 Boehm was selected to create a new depiction of Victoria that could be adapted for the coinage – even though the queen marked her 60th birthday that same year, some British coins still showed her as she appeared forty years previously. Boehm gave only intermittent attention to the project, and it took years before it came to fruition. The queen finally gave approval in early 1887, and the new coinage was prepared. Some of the reverse designs for the coinage were changed at the same time, depicting heraldic imagery and engraved by Leonard Charles Wyon.

When the new coins were released in June 1887, they proved a popular souvenir of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, but they were criticised for the diminutive crown, and because the reverse designs did not state the value of the coin. The sixpence was gilded by fraudsters to pass as a half sovereign, and it was quickly withdrawn by the Royal Mint, which resumed its old reverse design (stating its value), slightly modified. Royal Mint authorities began to consider replacing the Jubilee issue within a year of its release, and this may have been hastened by Boehm's death in 1890. A committee was created to consider replacements, and the Old Head coinage, with an obverse created by Thomas Brock, began to be struck in 1893.

Background and preparation

By the late 1870s, most denominations of British coins carried versions of the obverse design featuring Queen Victoria created by William Wyon and first introduced in 1838, the year after she acceded to the throne at the age of 18. The queen, approaching her 60th birthday, no longer resembled her numismatic depiction; and in February 1879, the private secretary to the queen, Sir Henry Ponsonby, informed the Deputy Master of the Royal Mint,[lower-alpha 1] Charles Fremantle, that Joseph Edgar Boehm had been engaged to produce a medallic likeness of the queen that could be adapted for coinage purposes. Born in Austria, Boehm had trained as a medallist and had undertaken several sculptural commissions for the royal family.[1]

There was no deadline for the commission, and Boehm throughout often put aside the portrait in favour of more pressing projects. In June 1879 Victoria recorded in her journal that she had "sat to Böhm for a Bas Relief" and in August Ponsonby wrote to Fremantle that the head was done, leading the deputy master to become more involved in the project. Nevertheless, in November, Boehm wrote apologising for his lack of progress. He wrote again on 1 January 1880, stating that he had completed several small models, and mentioning a small crown he had placed on Victoria's head. Although this would be similar in style to the 1877 Empress of India Medal, Fremantle was dubious about the headgear and wrote to Charles Francis Keary at the British Museum asking if there was precedent in numismatics for this. Keary replied that "in the case of Greek coins I need not add the crowns are put on as if meant to be worn and not to tumble off at the slightest movement".[2]

In January 1880 the queen's daughter, Princess Louise, viewed Boehm's work, and suggested a larger crown, and on 20 February, Victoria paid a call on the sculptor, and approved the revised crown. Fremantle visited Boehm three days later, and, still concerned about the crown, asked for advice from the Tower of London and from the College of Arms. Victoria sat for Boehm again on 28 February, and work had advanced to the point where Fremantle suggested having the Royal Mint's modeller and engraver, Leonard Charles Wyon (William's son) prepare steel coinage dies. Wyon did so, and pattern coins were struck several times over the next three years, but no version satisfied everyone involved. Boehm's design, with a crown fitting Victoria's head, was used for the Afghanistan Medal (1881). At the end of 1882, Fremantle proposed to Boehm that an entirely fresh start was needed, and the sculptor, busy with other commissions, agreed.[3]

Wyon was not initially involved in this second attempt, and Boehm invited the Viennese sculptor, Carl Radnitzky, under whom he had trained. Radnitzky stated that he had some of the work done by one of his students, whose identity is not known; the work may in fact have been done by Radnitzky himself. In August 1884 Fremantle had the chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Childers, show a pattern half crown to Victoria, who considered it a good likeness but criticised the fall of the veil on the coin, and stated that she preferred the existing coinage. By this time, the smaller crown had been placed upon her likeness again. Revisions were made, and more dies were sent from Vienna. In 1885 Leonard Wyon re-joined the project, and in January 1886 Fremantle authorised payment of 200 guineas (£210) to Boehm for his work to date, much of which was probably sent on to Radnitzky. By June of that year the project had advanced far enough that Fremantle told Boehm it would be desirable to have the new coins available for Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887. The queen approved the new effigy in July, when she sat for Boehm again. A report of the session in the Court Circular prompted Wyon, who would have preferred to make a design himself, to write sadly to Fremantle. Further revisions were necessary, and it was not until March 1887 that the new chancellor, George Goschen, approved the coins, dies for which were prepared from Boehm's models by Wyon. They were then taken to be approved by Victoria, who gave her consent, though her hope that the coins bear some indication of the jubilee was resisted by Fremantle, who wished to have dies sent in the next post to the Australian branch mints. He stated that as they were first struck in the jubilee year, the coins would always be "associated with the idea of the Jubilee".[4]

Designs

On the obverse of the Jubilee coinage, Victoria wears her small diamond crown, which she had bought so as not to have to wear a heavier one.[5] It was the crown that she preferred to wear at that time, and appears on other contemporary effigies of her.[6] Nevertheless, it quickly became controversial; as the numismatic authors, G. P. Dyer and P. P. Gaspar wrote in A New History of the Royal Mint, "the Boehm portrait, with its tiny crown in danger of tumbling off the back of the queen's head, attracted most criticism".[7] Sir John Craig in his earlier history, The Mint, deemed the effect of the small crown on Victoria's head "ludicrous".[5] Kevin Clancy, in his history of the sovereign coin, stated:

The presence of a small crown, which Victoria was actually fond of wearing, has often been cited as the chief flaw in the composition, but it was not the only weak link. Boehm, an accomplished sculptor, may have intended a faithful likeness but the elements of crown, widow's veil and extended truncation, drew attention to Victoria's pointed profile."[8]

Numismatic scholar Howard Linecar deemed the Jubilee head coinage "conservative in design, except only for that unfortunate crowned bust".[9] Richard Lobel, in Coincraft's Standard Catalogue of English and UK Coins, said that "the small crown placed on the back of the queen's head made her look a bit foolish".[10] André Celtel and Svein H. Gullbekk, in their book on the sovereign and its antecedents, describe the Jubilee head as "perhaps the least flattering of Victoria's coin portraits, presenting a middle-aged rather jowly looking queen wearing a disproportionately small crown on top of her widow's veil".[11] The numismatic writer Stephen Skillern explained that "the Jubilee portrait of the Queen had made no attempt to conceal or soften the results of time on the old Queen's face."[12] Numismatist Lawrence W. Cobb, writing in 1985, took a more nuanced view of the portrait: "Wyon seems to have tried to soften the Queen's look of age, tension and strain [on the medal], but in so doing he lost some of the strength and vigor of the Queen's indomitable spirit. Nonetheless, even with its faults, Wyon's portrait preserves the majesty of the Queen's presence."[13] Leonard Forrer wrote, "Unfortunately, his head of Queen Victoria was so much wanting in artistic merit, that it was severely criticised by all experts, and never gained favour with the public."[14]

As well as bearing the crown, Victoria's head has a widow's veil. Following the death of Albert (1861) she had remained in mourning, and the veil would have been black in colour.[9] The veil descends from a widow's cap worn under the crown.[13] The queen has a pearl necklace and there is an earring in her visible ear. She wears the ribbon and star of the Order of the Garter and the badge of the Order of the Crown of India; the artist's initials JEB are found on the truncation of her bust.[15]

For the various reverses, according to Dyer and Gaspar, "Fremantle had revived some of the finest heraldic designs from the past".[16] He felt that a reverse design with the denomination inside a wreath was "feeble", and sought artistic designs.[16] Fremantle selected designs originating with the Great Recoinage of 1816–1817 or even further back, and these were engraved by Wyon.[17] In 1873, soon after he had assumed the deputy mastership, Fremantle had secured the return of Benedetto Pistrucci's 1817 design of Saint George and the Dragon to the sovereign,[16] for the first time in almost half a century.[18] This design appeared on the gold sovereign, double sovereign and five-pound piece of the Jubilee coinage, and also on the silver crown, or five-shilling piece.[19] Beginning with the Jubilee coinage, a plume was restored to Pistrucci's design; it had featured in his original work, but had later been omitted.[20] The sixpence, shilling, florin, half crown, half sovereign and a new coin, the double florin, were given variations of the ensigns armorial of the United Kingdom. This was done in several guises: thus, according to the proclamation making them current that was issued in May 1887, the half sovereign had a "garnished Shield surmounted by the Royal Crown" while on the half crown, they were "in a plain Shield surrounded by the Garter, bearing the Motto 'Honi soit qui mal y pense' and the Collar of the Garter".[19] The half sovereign's reverse design was a slight modification to those of earlier Victorian half sovereigns, and its crowned shield did not differ much from designs used since the denomination had originated in 1817.[21] Each of the reverses for the sixpence and above carried the date of minting, but none carried a statement of the coin's monetary value.[22] The sixpence had borne a wreath surrounding a statement of its value since 1831,[23] with one reason for this being that it was the same size as the half sovereign, and was sometimes fraudulently plated to pass as one.[7]

The silver threepence, as well as the Maundy coinage (which would not appear with the new obverse until 1888, as the Royal Maundy had already occurred before the new coins were ready) carried their longtime designs (since 1822) of a wreathed and crowned number indicating their denominations,[24][25] though changes were made to the crown, and the Maundy twopence carried a different style figure 2. Leonard Wyon made those alterations from the designs of Jean Baptiste Merlen, and they are still used as the Maundy reverse designs.[26][27] No change was made to either side of the bronze coinage (the penny and its fractions) as there was then a large surplus of bronze pieces.[19] Nevertheless, pattern coins of the penny, halfpenny and farthing were prepared with obverse designs similar to Boehm's.[28] The Jubilee coinage bore shortened forms of the wording VICTORIA DEI GRATIA BRITANNIARUM REGINA FIDEI DEFENSOR (Latin for "Victoria by the grace of God queen of the British territories, Defender of the Faith").[19][29] The abbreviated form of Britanniarum is rendered as BRITT rather than with a single T – Gladstone, a classical scholar as well as a politician, had pointed out that the abbreviation of a Latin plural noun should end with a doubled consonant.[12]

Release and controversy

Initial release

On 12 May 1887, Fremantle officially announced that there would be changes to the gold and silver coinage, including the introduction of a double florin, and an Order in Council to that effect was printed in The London Gazette on 17 May. Later that month, the Annual Report of the Deputy Master of the Mint contained engravings of the new issue;[22] The Ipswich Journal opined on 10 June that "I think that when they are in circulation the public will admit they [the new coins] are a distinct artistic advance on the majority of those at present in use".[30] The same day, Church Times complained, "We cannot join in the applause which has been bestowed upon the George of Pistrucci, which is retained for the sovereign. It is not likely that anybody going out to fight dragons would forget to put on any clothes except a helmet, a cloak, and a pair of shoes."[31]

The official release date of the Jubilee coins was initially set for 21 June, the date on which the queen's Golden Jubilee was to be celebrated.[32] Since this day had been proclaimed a bank holiday, the release date was changed to 20 June, on which date the coins were to be conveyed from the Royal Mint to the Bank of England and there used to fill orders from London banks. Provincial banks would not have the new coins until at least the 22nd.[33] Small quantities were available at the London banks on Saturday, 18 June.[34] The Irish banks in Dublin were able to supply the silver coins to the public on the 20 June, as supplies had been brought over from the Royal Mint on the 18th, though the Freeman's Journal of Dublin reported that the gold coins were not expected to be available there until the 22nd.[35] The Royal Mint's efforts to distribute the coins were hampered by an accident to the die for the crown coin, which was spoilt.[34]

Once the new coins were released, there was a deeply negative reaction by public and press. According to Dyer and Stocker:

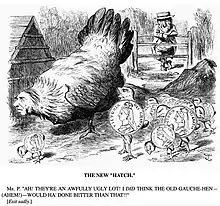

When the storm of condemnation erupted, Fremantle seemed genuinely taken aback at 'the sad turn affairs have taken, most unexpected to me'. It was some storm: questions in parliament, outspoken criticism from all sections of the press, derisive cartoons and doggerel in Fun and Punch, and even some unfriendly comment by John Evans in his presidential address to the Numismatic Society. The coinage was seen as the worst of all worlds; poorly executed, undignified on the obverse, and inefficient in not specifying values on the reverse.[36]

The Standard wrote on 29 June, "The portrait of the Queen is not a bad likeness, though certainly not a pleasing or a dignified one. As to the Crown and the head-dress they are quite unnecessary and a distinct disfigurement."[37] The Freeman's Journal stated, "Those who have seen the new coins are not taken with them. The bust of the Queen with the crown toppling off the back of her head is not conducive to artistic merit [...] the smaller silver coins bear no record of their value, which is another drawback. Altogether the Jubilee coinage is not likely to create much enthusiasm."[35] The Western Mail of Cardiff stated that "The head of the Queen on all the coins is also generally objected to, her Majesty having none of the dignified appearance she is accustomed to present on State occasions, and the miniature crown being almost pitiable in its paltriness."[34] The Birmingham Daily Post wrote on 24 June:

As to the coins generally, they are singularly poor in design and feeble in execution. We have many die-sinkers in Birmingham who would have been ashamed to turn them out; and if the Mint can do nothing better, some of our own medalists might well be permitted to try their hands, with the certain result of redeeming the credit of the national coinage [...] unless a change is made sixpences will be electro-gilt and passed off as half-sovereigns by wholesale, for there is no appreciable difference between the two coins, either in weight or appearance [...] the worst thing of all about the coinage is, however, the portrait of the Queen; which is neither valuable as an accurate representation of Her Majesty, nor dignified if it is to be taken as an idealised effigy; while the odd-looking little crown, which seems to be falling off, renders the portrait absolutely ludicrous.[38]

Boehm's fellow artists joined in the chorus. Edward Poynter, opening an art exhibition in South Kensington on 28 July, stated, "The head was modelled by Mr Boehm, and making all allowance for the necessity of pleasing an illustrious patron, that may have led Mr Boehm to accept such structural absurdities as the toy crown and the straight veil, it was difficult to believe that a sculptor of his eminence should have turned out such a thoroughly bad work. For the head is bad all over [...] Some of the new heraldic devices are the poorest things of the kind we have ever had."[39] Lewis Foreman Day criticised the new coins in The Magazine of Art, "British sculptors are justly aggrieved when a production is put forth, presumably as the best we can do, when they themselves know it to be very far from representing the standard of national design, and it aggravates their grievance to think that the favoured artist bears not even an English name".[40]

This criticism entered the House of Commons, where Goschen answered questions about the new coinage on 23 and 28 June. The chancellor told MPs that Royal Mint officials preferred artistic designs from past times for the coinage rather than text stating their values. The public, however, did not confuse the florin and half crown, and they would not confuse the double florin and crown. The Conservative MP, Lewis Henry Isaacs, asked whether the coins could be called in and more suitable designs made. Goschen responded that public demand for the new coins had been so great a premium was being paid for the five-pound piece and that the depiction of the queen was similar to other authorised depictions of her.[41]

Continued circulation

The five-pound and two-pound pieces did not circulate to any great extent, and were kept primarily as souvenirs.[42] Nevertheless, this was the first time the Royal Mint had struck a five-pound piece available for general circulation, previous issues being proof coins or pattern pieces.[43] Soon after the issuance of the new coins, there was an outcry because the new sixpence was identical in size and similar in design to the half sovereign, and was gilded to pass as one. Although the shilling was similar in size to the sovereign, and had lost the statement of its denomination in the redesign, it was less often gilded as the reverses of the two coins did not resemble each other. The Numismatic Magazine's July 1887 issue noted that production of the new sixpence had been stopped pending enquiries. Before the end of the year, the Royal Mint had resumed production of the sixpence's former design, with a crowned wreath surrounding the words SIX PENCE, though paired with Boehm's Jubilee head obverse. The new sixpence design differs slightly from the earlier one, as the crown was redesigned and other changes made.[44] These were made current by a proclamation dated 28 November 1887.[45]

By September, The Graphic was reporting that the new coins were scarce in circulation, and there was talk that many of them had been sent to the colonies. The withdrawn sixpence carried a premium, as did the five-pound piece, and some crowns had been gilded to pass for the five-pound coin.[46] The Sheffield Independent's London correspondent reported on 17 September that the withdrawn sixpences were passing for half a crown each, and that in addition to the quantities of coin sent to the colonies, large amounts had been absorbed by jewellers, who placed them in ornaments, and by visitors to London seeking souvenirs of the Jubilee, especially Americans.[47]

In May 1888 Fremantle reported that, though "the issue of the new coins was received with some adverse criticism", there had been a considerable demand for them – well above what was needed for circulation, leading to the largest number of silver coins issued in several years.[48] Beyond the sixpence, there was no immediate move to replace the Jubilee coinage; the numismatist, Jeffery L. Lant, explained that "the Jubilee coinage was popular with the public notwithstanding the criticism directed against it. It constituted, initially, the best form of Jubilee keepsake".[49] He pointed out that the Royal Mint sold 1,881 proof sets of the 1887 Jubilee coinage at a price of 11 guineas (£11 11s, that is, eleven pounds and eleven shillings or £11.55 in decimal reckoning), about 25 percent above the face value, and the demand for the sets and for the Jubilee medal bearing a similar bust of Victoria by Boehm was such that work was not completed until the end of 1888. The Royal Mint was so busy striking Jubilee coins that extra money for labour costs had to be requested. These factors made it easy for the Royal Mint to wait until some time after the Jubilee to consider a replacement.[49] Goschen wrote to Ponsonby in September 1889, "As the general discussion on the Jubilee coinage had subsided, and the public appeared to have got used to the new coin, I thought that it might possibly be best to let the matter rest for a while."[50]

Groats, or fourpence pieces, had not been struck for circulation in Britain since 1855. Disliked because they were the same diameter (though somewhat thicker) than the threepenny bit, they retained some popularity in Scotland, and circulated in British Guiana as the equivalent of a quarter guilder. An issue of groats was made in 1888, the last of its series. Although valid currency in the United Kingdom, they were intended for British Guiana, and bore Boehm's Jubilee head on the obverse, with the William Wyon reverse used since the currency groat's initial issuance in 1836.[51]

Victoria took the opportunity, when inspecting proposed changes to the shilling in June 1888, to lobby Goschen for the inclusion of her title as empress of India (INDIAE IMPERATRIX, abbreviated as IND. IMP. on the coinage). Since the act allowing Victoria to assume the Indian title had forbidden its use in the United Kingdom, Goschen took no action on the request, but Victoria got her way with the following issue of coins, which debuted in 1893,[52] as the cabinet ruled in 1891 that the abbreviation could appear as British coins also circulated in the colonies.[53]

In 1889 both sides of the shilling were slightly altered, with a larger version of Boehm's effigy of Victoria being approved by the queen, and slight changes made to the reverse.[54] Nevertheless, in September 1889, Victoria wrote, "the Queen dislikes the new coinage very much, and wishes the old one could still be used and the new one gradually disused, and then a new one struck".[55] In reply Goschen promised to confer with Royal Mint authorities as to possible options.[50]

Replacement and end of series

The double florin had been controversial, some questioning the need for such a piece or complaining it was too near in size to the crown coin. Anecdotes of losses sustained by publicans and their help, who accepted the double florin under the misapprehension it was a five-shilling piece, led to it being dubbed the "Barmaid's Ruin". The government attempted to increase its circulation by including it in pay packets for its workers, but minting was stopped, as it proved permanently, in August 1890.[15][56]

The death of Boehm in December 1890 set the Royal Mint free to consider replacement designs without being concerned about grieving the queen's favourite sculptor, and in February 1891, Goschen appointed a Committee on the Design of Coins with Sir John Lubbock as chairman, and including Fremantle and such notables as Sir Frederic Leighton, president of the Royal Academy. The committee's remit was "to examine the designs on the various coins put into circulation in the year 1887, and the improvements in those designs since suggested, and to make such recommendations on the subject as might seem desirable, and to report what coins, if any, should have values expressed on them in words and figures".[57] At its first meeting, on 12 February 1891, the committee recommended that the double florin not be further struck, something confirmed in parliament by Groschen on 25 May.[58]

A competition was held, and several invited sculptors were asked to submit two versions of a proposed new obverse for the coinage by 31 October. An obverse design by Sir Thomas Brock depicting Victoria wearing a diadem and a veil was chosen for the obverse. The committee decided to retain Pistrucci's George and Dragon design on the coins it appeared upon, as well as expanding it to the half sovereign. Reverse designs, some by Brock and some by Poynter, were determined upon for the other coins of sixpence and above, and the committee recommended the value appear on all coins from the threepence to the half crown.[59] A royal proclamation for the new coins was promulgated on 30 January 1893, and the new coins met a favourable reaction.[60] Some 1893 sovereigns were struck with Boehm's design at the Australian branch mints,[61] and half sovereigns of that type were minted both at London and in Australia.[62] Of the silver coinage, some 1893 sixpences and threepence with Boehm's obverse were struck at London,[63] but otherwise, the Jubilee coinage was at an end.[10][64]

The Jubilee head coins

| Denomination | Obverse | Reverse | Reverse designer and first year used on denomination | Years struck with Jubilee obverse and most recent later usage of reverse on this denomination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-pound piece |  |

|

Benedetto Pistrucci[65] (1887)[66] | 1887 (London and Sydney mints).[66] Reverse most recently used in 2024.[67] |

| Double sovereign |  |

|

Benedetto Pistrucci[68] (1823)[69] | 1887 (London and Sydney mints).[70] Reverse most recently used in 2024.[67]

|

| Sovereign | .jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) |

Benedetto Pistrucci[67] (1817, major modification in 1821)[71] | 1887–1892 (London Mint) 1887–1893 (Melbourne Mint) 1887–1893 (Sydney Mint)[61] Reverse most recently used in 2024.[67] |

| Half sovereign |  |

|

Leonard Charles Wyon[17] (1887 modification of 1838 design by Jean Baptiste Merlen)[62] | 1887, 1890–1893 (London Mint) 1887, 1893 (Melbourne Mint) 1887, 1889, 1891 (Sydney Mint)[72] |

| Crown |  |

|

Benedetto Pistrucci[73] (1818, major modification in 1821)[74] | 1887–1892.[75] Reverse most recently used in 1951.[76] |

| Double florin |  |

|

Leonard Charles Wyon[77] (1887)[77] | 1887–1890[77] |

| Half crown |  |

|

Leonard Charles Wyon[17] (1887)[78] | 1887–1892[78] |

| Florin |  |

|

Leonard Charles Wyon[79] (1887)[80] | 1887–1892[81] |

| Shilling |  |

|

Leonard Charles Wyon[17] (1887)[82] | 1887–1892[82] |

| Sixpence (withdrawn type) |  |

|

Leonard Charles Wyon[17] (1887)[83] | 1887[83] |

| Sixpence |  |

|

Leonard Charles Wyon[17] (1887 modification of 1831 design by Jean Baptiste Merlen)[84] | 1887–1893.[83] Reverse last used in 1910.[85] |

| Groat (fourpence) |  |

|

William Wyon[86] (1836)[87] | 1888[86] |

| Threepence |  |

|

Jean Baptiste Merlen (1822).[88] Crown redesigned 1887 by Leonard Charles Wyon[17][88] | 1887–1893.[88] Reverse last used in 1926.[89] |

| Maundy coinage |  |

|

Jean Baptiste Merlen (1822).[90] Crown redesigned 1888 by Leonard Charles Wyon.[26] | 1888–1892.[91] Reverse remains in use as of 2023.[91][92] |

Notes

References

- ↑ Dyer & Stocker, p. 274.

- ↑ Dyer & Stocker, p. 275.

- ↑ Dyer & Stocker, pp. 275–277.

- ↑ Dyer & Stocker, pp. 277–280.

- 1 2 Craig, p. 342.

- ↑ Dyer & Stocker, p. 281.

- 1 2 Dyer & Gaspar, p. 536.

- ↑ Clancy, p. 75.

- 1 2 Linecar, p. 110.

- 1 2 Lobel, p. 65.

- ↑ Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 108.

- 1 2 Skillern, p. 31.

- 1 2 Cobb, p. 257.

- ↑ Forrer, p. 258.

- 1 2 "Item NU 1124 Coin – Double-florin, Queen Victoria, Great Britain, 1889". Museums Victoria. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 Dyer & Gaspar, p. 535.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dyer & Stocker, p. 282.

- ↑ Linecar, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 4 Lant, p. 134.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 454.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 467–469.

- 1 2 Lant, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 546–547.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 555–556, 564–565.

- ↑ Seaby, p. 160.

- 1 2 Robinson, p. 49.

- ↑ Linecar, p. 103.

- ↑ Peck, pp. 493–495.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 416–417.

- ↑ "Notable Events and Prominent Personages". Ipswich Journal. 10 June 1887. p. 5.

- ↑ Lant, p. 135.

- ↑ "The New Coinage". Sheffield Independent. 28 May 1887. p. 8.

- ↑ "The New Coins". Dundee Courier. 10 June 1887. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 "London Correspondence". Western Mail. Cardiff, Wales. 21 June 1887. p. 2.

- 1 2 "The Jubilee Celebrations in Dublin". Freeman's Journal. Dublin. 21 June 1887. p. 6.

- ↑ Dyer & Stocker, p. 280.

- ↑ Lant, p. 136.

- ↑ "News of the Day". Birmingham Daily Post. 24 June 1887. p. 4.

- ↑ Lant, p. 139.

- ↑ Day, p. 420.

- ↑ Lant, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Seaby, p. 157.

- ↑ Celtel & Gullbekk, p. 109.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 547.

- ↑ Lant, p. 138.

- ↑ "Topics of the Week". The Graphic. 17 September 1887. p. 298.

- ↑ "Notes From London". Sheffield Independent. 17 September 1887. p. 5.

- ↑ "The Jubilee Coinage". The Standard. 30 May 1888. p. 5.

- 1 2 Lant, p. 140.

- 1 2 Stocker, p. 67.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 47, 559–560.

- ↑ Lant, pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Stocker, p. 76.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 534–536.

- ↑ Dyer & Stocker, p. 283.

- ↑ Dyer, pp. 114–117.

- ↑ Stocker, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Stocker, p. 68.

- ↑ Stocker, pp. 68–77.

- ↑ Stocker, p. 80.

- 1 2 Lobel, pp. 456–457.

- 1 2 Lobel, pp. 468–469.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 549, 565.

- ↑ Lant, p. 141.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 427–428.

- 1 2 Lobel, p. 428.

- 1 2 3 4 "The sovereign 2024 five-coin gold proof set". Royal Mint. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ↑ "The Double Sovereign 2021 Gold Bullion Coin". Royal Mint. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 439.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 440.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 453.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 469–470.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 488.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 486–488.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 490.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 492.

- 1 2 3 Lobel, p. 495.

- 1 2 Lobel, pp. 510–511.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 517.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 518–519.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 519.

- 1 2 Lobel, pp. 535–536.

- 1 2 3 Lobel, pp. 548–549.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 547–549.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 548–550.

- 1 2 Lobel, pp. 559–560.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 559.

- 1 2 3 Lobel, pp. 564–566.

- ↑ Lobel, p. 567.

- ↑ Lobel, pp. 555–556, 564.

- 1 2 Lobel, p. 556.

- ↑ "The Royal Mint Unveils His Majesty King Charles III's Official Maundy Money Coins". Royal Mint. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

Bibliography

- Celtel, André; Gullbekk, Svein H. (2006). The Sovereign and its Golden Antecedents. Oslo, Norway: Monetarius. ISBN 978-82-996755-6-7.

- Clancy, Kevin (2017) [2015]. A History of the Sovereign: Chief Coin of the World (second ed.). Llantrisant, Wales: Royal Mint Museum. ISBN 978-1-869917-00-5.

- Cobb, Lawrence W. (February 1985). "The Veiled Queen". The Numismatist: 255–259.

- Craig, John (2010) [1953]. The Mint (paperback ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-17077-2.

- Day, Lewis F. (1887). "New Coins for Old". The Magazine of Art: 416–420.

- Dyer, G. P. (1995). "Gold, Silver and the Double Florin" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 64: 114–125.

- Dyer, G. P.; Gaspar, P. P. (1992). "Reform, the New Technology and Tower Hill". In Challis, C. E. (ed.). A New History of the Royal Mint. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 398–606. ISBN 978-0-521-24026-0.

- Dyer, G. P.; Stocker, Mark (1984). "Edgar Boehm and the Jubilee Coinage" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 54: 274–288.

- Forrer, Leonard (1904). Biographical Dictionary of Medallists: Coin, Gem, and Seal-engravers, Mint-Masters, &c., Ancient and Modern, with References to Their Works B. C. 500-A. D. 1900. Vol. 1. Spink & Son ltd., London. p. 258.

- Lant, Jeffrey L. (1973). "The Jubilee Coinage of 1887" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 43: 132–141.

- Linecar, Howard W.A. (1977). British Coin Designs and Designers. London: G. Bell & Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7135-1931-0.

- Lobel, Richard, ed. (1999) [1995]. Coincraft's Standard Catalogue English & UK Coins 1066 to Date (5th ed.). London: Standard Catalogue Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9526228-8-8.

- Peck, C. Wilson (1960). English Copper, Tin and Bronze Coins in the British Museum 1558–1958. London: Trustees of the British Museum. OCLC 906173180.

- Robinson, Brian (1992). Silver Pennies & Linen Towels: The Story of the Royal Maundy. London: Spink & Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-0-907605-35-5.

- Seaby, Peter (1985). The Story of British Coinage. London: B. A. Seaby Ltd. ISBN 978-0-900652-74-5.

- Skillern, Stephen (October 2013). "The coinage of Edward VII, Part I". Coin News: 31–33.

- Stocker, Mark. (1996). "The Coinage of 1893" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 66: 67–86.