Joseph LaBarge | |

|---|---|

Steamboat captain Riverboat trader, Steamship builder | |

| Born | October 1, 1815 |

| Died | April 3, 1899 (aged 83) St. Louis, Missouri |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Steamboat captain |

| Years active | 50+ |

| Known for | Setting multiple speed and distance records on the Missouri River |

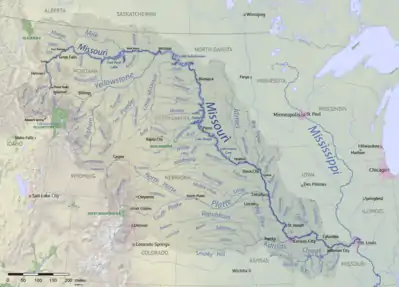

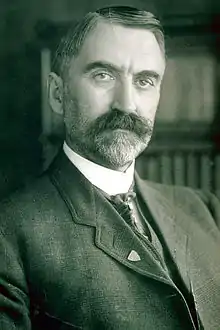

Joseph Marie LaBarge[lower-alpha 1] (October 1, 1815 – April 3, 1899) was an American steamboat captain, most notably of the steamboats Yellowstone, and Emilie,[lower-alpha 2] that saw service on the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, bringing fur traders, miners, goods and supplies up and down these rivers to their destinations. During much of his career LaBarge was in the employ of the American Fur Company, a giant in the fur trading business, before building his own steamboat, the Emilie, to become an independent riverman. During his career he exceeded several existing speed and distance records for steamboats on the Missouri River. Passengers aboard his vessels sometimes included notable people, including Abraham Lincoln. LaBarge routinely offered his steamboat services gratis to Jesuit missionaries throughout his career.

LaBarge managed to avoid the first cholera epidemic in the United States, which at that time killed half the crew aboard the Yellowstone. After years of success in the shipping business, LaBarge, his brother, and other partners formed their own trading firm on the upper Missouri River. A steamboat captain for more than fifty years, LaBarge was considered the greatest steamboat man on the Missouri River, and was among the first steamboat pilots to navigate the uppermost Missouri River in the 1830s. His long career as a riverboat captain exceeded 50 years and spanned the entire era of active riverboat business on the Missouri River.

Early life

Joseph LaBarge was born on Sunday, October 1, 1815, in St. Louis, Missouri. His father was Joseph Marie LaBarge, Senior and his mother was Eulalie Hortiz LaBarge. He was the second of seven children, three boys and four girls, who all survived to adulthood.[3] His father, at the age of 21, traveled from Quebec in a birch-bark canoe over lakes and rivers and settled in St. Louis at a time when the city was the center of the enormous fur trade. LaBarge Senior fought in the War of 1812, most notably at the Battle of Frenchtown where he lost two fingers during the battle.[4] LaBarge Senior was a trapper who also worked as a guide and engaged in many trapping expeditions in the upper Missouri River. He was considered a riverman in his own right; subsequently all three of his sons, Joseph, John and Charles, aspired to the trade and became riverboat pilots.[5][6][lower-alpha 3]

Not long after Joseph was born his parents bought and moved to a farm in Baden, Missouri, six miles distant from St. Louis.[lower-alpha 4] The area was mostly unsettled at the time and Sac and Fox Indians roamed the area and were at times aggressive and hostile. The infant LaBarge and his mother were once accosted by Indians while she was working in the garden, with LaBarge's father fending them off by presenting gun in hand. As a young lad, LaBarge was said to have exceptional ability as a runner and swimmer, and excelled in the various games and sports of the day.[8]

Joseph LaBarge's early education was somewhat limited given the basic and unrefined schools in St. Louis during his childhood days. He first attended classes at the residence of Jean Baptiste Trudeau, a noted and reputable teacher in St. Louis, where he studied the common branches in education, all in French. Knowing that their son needed to speak English fluently in order to make his way in America, his parents sent him to schools where instruction was given in English. To that end Joseph's next teacher was Salmon Giddings, the founder of the First Presbyterian Church in St. Louis, and after, to a more prestigious school taught by Elihu H. Shephard, considered an excellent teacher. His command of English would come slowly, but eventually he mastered the language. At age twelve Joseph attended Saint Mary's College in Perry County for three years. His parents had intended to educate their son for the priesthood, and Joseph's curriculum at Saint Mary's was selected for that purpose. However, the young LaBarge did not aspire to such vocation and began associating with young ladies to the extent where he was not allowed to finish school at Saint Mary's. At age fifteen he began working as a store clerk in a clothing store.[6][9]

Among the prominent events LaBarge witnessed in his childhood, was the celebrated visit to the United States by Lafayette in 1825, while he was in St. Louis. Lafayette was greeted by the Mayor and escorted by a company of cavalry on horseback, along with a company of uniformed boys, of whom the ten-year-old LaBarge was one. Lafayette shook hands and spoke inquisitively with each of the youths, which would prove to be an event LaBarge would reminisce about into his old age.[10]

LaBarge wore a full beard most of his adult life and in his later years was said to bear a striking resemblance to General Ulysses S. Grant.[11] LaBarge married Pelagie Guerette on August 17, 1842, whom he knew since his childhood.[12] Pelagie was also born in St. Louis, on January 10, 1825. One of the first water-driven mills in St. Louis was built and operated by her father, a millwright and architect.[13] They had seven children. LaBarge was a lifelong Catholic in religion, and in politics, a lifelong Democrat.[14]

Career on the river

The demands of the fur trade were largely responsible for the advent of steamboat use on the Missouri River, and by 1830 the young LaBarge bore witness to the steamboats coming to and departing Saint Louis, which were employed in the service of this trade, their principal business in the mid-nineteenth century. Answering the high demand for furs in the East and in Europe, the American Fur Company,[lower-alpha 5] dominated the fur trade and made regular and frequent use of steamboats.[15] From 1831 to 1846 steamboat navigation on the upper Missouri River was confined almost entirely to riverboats owned by the American Fur Company. Among these vessels were the Yellowstone, and the Spread Eagle, both of which would eventually be piloted by LaBarge during the course of events.[16]

Not content working as a shop clerk, the young LaBarge joined the crew of the steamboat Yellowstone,[lower-alpha 6] serving as a clerk, when the vessel was engaged in the sugar trade in the lower Mississippi River. In 1831 the Yellowstone made her first trip up the Missouri River, and was now in the employ of the American Fur Company. The Yellowstone was to proceed to the lower Mississippi to the bayou La Fourche. Since LaBarge spoke both English and French, his services were found useful. The following spring, LaBarge signed a three-year contract to serve as a clerk for the American Fur Company at a salary of $700. He returned to the Yellowstone and traveled up the Missouri River to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where he worked in the flourishing fur trade along the Missouri River.[6][18] LaBarge earned his Master's license for piloting riverboats at the age of 25.[19]

Journeys aboard the Yellowstone

In 1833 LaBarge, aboard the steamship Yellowstone, left Saint Louis and was headed for Fort Pierre on the upper Missouri River.[lower-alpha 7] One of the passengers aboard was Prince Maximilian, a German explorer and naturalist. Returning to Saint Louis, another cargo was loaded, to be taken to Council Bluffs. During this voyage an epidemic of cholera broke out in the general area[lower-alpha 8] and claimed the lives of many of the crew members, forcing Captain Anson G. Bennett to stop at the mouth of the Kansas River until he could return to Saint Louis and get replacements for the crew. Before leaving, he assigned LaBarge the charge of the steamboat; this is when LaBarge, at age 18, began his fifty-year career as a riverman and steamboat pilot.[20][lower-alpha 9]

While Bennett was away, the remainder of the crew died; LaBarge buried their bodies in a trench-grave alongside the Missouri.[22] When news of the cholera outbreak aboard the Yellowstone spread, a pro tempore board of health from Jackson County ordered the boat to move on, threatening to burn the craft if it remained.[23] Now acting as both pilot and engineer, and realizing the danger, LaBarge took the boat up a short distance from the mouth of the Kansas on the west shore of the Missouri, where there were no inhabitants.[24][25]

On Captain Bennett's return the boat proceeded on her voyage up the Missouri and arrived at the mouth of the Yellowstone on June 17, becoming the first steamboat to reach the mouth of the Yellowstone.[25] The cargo still aboard was consigned to Cyprian Chouteau who owned a trading post ten miles up the Kansas River. Captain Bennett gave orders to LaBarge to turn over the cargo to the consignees before he left. LaBarge, accordingly, set off on foot to find the trading post and tell Chouteau to come and get his goods. About a mile from the trading post, which had quarantined itself from the cholera epidemic, LaBarge was intercepted by a man stationed there, wary of the outbreak, and watching for anyone coming from Missouri. LaBarge was not permitted to proceed and was threatened to be shot if he persisted. LaBarge agreed to remain where he was if the man would inform Chouteau of the purpose of his arrival.[6][11][26]

Other ventures

During the summer of 1838, LaBarge was serving as pilot aboard the steamboat Platte. Twelve miles downriver from Fort Leavenworth one of the guys of the yawl derrick broke, sending the yawl adrift down the river. The yawl was so essential for navigating the steamboat up the Missouri River that its loss would have proven irreparable. Aware of the possible predicament, LaBarge jumped into the river and swam over to the yawl, gained control and landed it a short distance downstream from the Platte, an episode which demonstrated LaBarge's ability as a swimmer.[15]

In 1847, acting as captain and pilot aboard the steamboat Martha,[lower-alpha 10] LaBarge journeyed up the Missouri River carrying supplies for various Indian tribes on the upper Missouri River. For several years Captain Sire had made this journey but had decided to retire from the river, leaving LaBarge in command of the boat and in charge of the company's business. LaBarge's wife, Pelagie, was also aboard. The trip north went without incident until they arrived at Crow Creek in the Dakota Territory, not far from a trading post owned and operated by Colin Campbell, who had a large supply of fire-wood ready as fuel for the steamer. In an effort to prevent refueling the vessel, a raiding party of Yanktonian Sioux Indians took possession of the woodpile, demanding payment. During the incident they boarded the vessel and killed one of the crewmen, and then drowned the boiler fires. Aboard the boat was a cannon which was in the engine room having its carriage repaired. While the Indians were occupied towards the front of the vessel LaBarge had the cannon brought up to the cabin and loaded. Lighting a cigar and, holding the cannon in plain view of the Indians, he directed them to leave at once or he would "blow them all to the devil". In a panic, the fleeing Indians fell over one another to get off the boat.[13][27]

In 1850 LaBarge was making a voyage aboard the steamer Saint Ange heading for Fort Union,[lower-alpha 11] on the upper Missouri River in the dense wilderness of north-west North Dakota. LaBarge's wife and other ladies were aboard, his wife being among the first white women to ever see the fort.[29] Along the way a boy fell overboard from the forecastle. LaBarge was nearby and immediately dove into the river and seized him, keeping the boy from being taken in by the steamboat's sidewheel and got the youth safely to shore, an event that again demonstrated LaBarge's ability as a skilled swimmer.[30]

Riverfront scene, depicting riverboat activity

LaBarge exceeded the existing speed record for steamboats on the Missouri that year when he piloted Saint Ange, with more than a hundred passengers aboard, from Saint Louis to Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone River in twenty-eight days. The next year, departing from Saint Louis, he set yet another record with the same steamboat to the Poplar River, the farthest point north on the Missouri river ever reached by a steamboat. Aboard were the notable Jesuit missionaries, Fathers Pierre-Jean De Smet and Christian Hoecken, Catholic missionaries who were working with and teaching Christianity to the various Indian tribes in the North country.[31][32][lower-alpha 12] LaBarge was a close friend of De Smet, and always offered the services of his steamboat to the Catholic missionary effort.[33] After LaBarge's record-breaking journey he sold the Saint Ange and retired temporarily at age thirty-six with the fortune he had amassed. Two years later he was back on the river, buying, selling and building steamboats. Before long he was in the trading business once again. In 1855 the American Fur Company sold Fort Pierre, which was also used as a trading post, to the U.S. government. At that time LaBarge had purchased and supervised the completion of a new steamboat he named the Saint Mary, which he used in making the transfer of the former post to the War Department's new post further north in South Dakota, near Chantier Creek, and in moving the Fur Company's inventory and supplies there. LaBarge was then commissioned to transport army personnel to the newly acquired fort.[34][35]

In 1852, Captain Edward Salt-Marsh arrived from Ohio to Saint Louis with the Sonora, a steamboat that LaBarge considered "an excellent craft". After learning it was up for sale, and following lengthy negotiations, LaBarge purchased the Sonora from the captain for $30,000. Using the Sonora, he made a trip up to Fort Union with their annual outfit of supplies. His next order of business took him to New Orleans where he operated for the remainder of the season, and found plenty of business left by many captains and crews who abandoned the city because of a yellow fever scare. That autumn he sold the Sonora and purchased a smaller vessel, the Highland Mary, which he put to work in the lower Missouri river during the entire season of 1853, after which he sold this vessel that autumn.[36]

By 1854 Captain LaBarge was commissioned by the U.S. government most of the time. During the previous winter Colonel Crossman, of the U.S. Army Quartermaster stationed in St. Louis, contracted a shipbuilding company operating on the Osage River for a steamboat for use by the government. It would be named the Mink. When the hull was almost completed LaBarge brought the boat down into the river and supervised her completion and worked as her pilot during the entire season.[37]

Journey with brother

As early as 1834, new speed and distance records for steamboats were being established on the Missouri River. That year the steamboat Assiniboine reached a point near the mouth of Poplar River, a hundred miles above the Yellowstone River, but because of low water levels remained there for the duration of the winter. This remained the farthest point reached by steamboats until 1853 when the steamboat El Paso surpassed this point by 125 miles (201 km), five miles above the mouth of Milk River, which came to be known as El Paso point. This marked the uppermost limit of steamboat navigation for the following six years.[38]

In the spring of 1859 the American Fur Company sent two vessels up the Missouri River, commanded by LaBarge and his brother, John, with its annual outfit of men and supplies. The Company employed its own boat, the Spread Eagle, and chartered a second riverboat, called the Chippewa. It was a light vessel and her owner, Captain Crabtree, was contracted to reach Fort Benton, 31 miles below the Great Falls, or as far past this point as was possible.[lower-alpha 13] At Fort Union Crabtree defaulted in his contract and the Chippewa was sold to the company for a sum about equal to its charter price. At this time, freight from the Spread Eagle was transferred to the Chippewa. The Spread Eagle was commanded by Captain LaBarge, while his brother, John, assumed command of the Chippewa. On July 17, 1859, the Chippewa made her way successfully, to within fifteen miles of Fort Benton, and unloaded her cargo at Brule bottom, where Fort McKenzie had once stood. In so doing she had thus managed to reach a point further from the sea by river navigation than any other boat had up to this time.[38]

Independent

LaBarge permanently ended his service to the American Fur Company in 1857 and spent the next three years mainly on the lower Missouri river, rarely venturing beyond Council Bluffs, Iowa. By the summer of 1859 he built himself a new steamboat, considered one of the best vessels to navigate the Missouri River. Pierre Chouteau, Jr., LaBarge's former employer from the American Fur Trade, having heard about his undertaking, offered any assistance he may have needed, as the Company still valued LaBarge's services and would gladly have given him employment again. Having thanked Mr. Chouteau, LaBarge declined his offer. Upon completion of his new steamboat, LaBarge named her the Emilie, after one of his daughters. LaBarge was now the proud owner, designer, builder, and master of his own private riverboat. The Emilie soon became one of the most famous boats on the Missouri River. She was a sidewheel vessel, 225 feet (69 m) in length, had a beam of 32 feet (9.8 m), with a hold 6 feet (1.8 m), and could easily carry cargoes of up to 500 tons.[lower-alpha 14] The riverboat proved to be an exceedingly beautiful vessel. LaBarge embarked on Emilie's maiden voyage on October 1, 1859, which happened to be his forty-fourth birthday.[41][42] In the summer of 1859 Abraham Lincoln came west and toured the Missouri River looking into real estate investments, where LaBarge saw the future president for the first time. Lincoln was a passenger on the Emilie, which carried him to Council Bluffs.[43][40]

During autumn of that year, river ice prevented the Emilie from proceeding while docked near Atchison, Kansas, which kept LaBarge there for the duration of the winter. When spring arrived the citizens of Atchison, offering to supply fuel for his steamboat, asked LaBarge if they could employ his steamboat for use as an ice-breaker to open a passage between Atchison and Saint Joseph, some twenty miles to the north. LaBarge maneuvered the bow of his boat up on to the ice and with its enormous weight broke through, doing this repeatedly to Saint Joseph. The next year the winter's river ice once again caught LaBarge and the Emilie near Liberty, Missouri. While detained there he heard the news that his former passenger, Lincoln, had been elected president. A few months later the Confederates fired upon Fort Sumter in South Carolina and the Civil War became a reality.[40][44]

Civil War era

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, people along the Missouri River were largely sympathetic to the South. Although somewhat sympathetic also, Captain LaBarge remained loyal to the Union and took an oath of allegiance to the Union, not wanting to see the nation divided.[5] While operating on the Missouri River, Confederate general John S. Marmaduke, whom LaBarge knew well, placed LaBarge under arrest and seized his boat and crew at Boonville and ordered him to transport Sterling Price, another Confederate general who was ill, to Lexington, Missouri. LaBarge and his crew were free to leave, but he knew that news of his help to the Confederates would soon reach Union authorities. He subsequently appealed to General Price, explained his situation, and asked him for help. Price wrote a letter for him, stating that LaBarge had acted under duress and was forced to help against his repeated protests. The incident landed LaBarge in trouble with Union authorities, but under the circumstances he was allowed to continue operating on the river for the remainder of the war.[6][45]

In the winter of 1861–1862 LaBarge and several partners formed the firm of LaBarge, Harkness & Co., based in Saint Louis, for purposes of trading on the upper Missouri River. Members of the firm included LaBarge, his brother John, James Harkness, William Galpin and Eugene Jaccard. Each member put up $10,000 with which two steamboats were purchased; The Emilie, a large steamer, and the Shreveport, a shallow draft vessel. The LaBarge brothers managed affairs concerning the steamboats, while Harkness went to Washington to obtain the necessary permits from the Interior Department, and to establish friendly relations with the Office of Indian Affairs.[2][46] Supplies and tools were also purchased for building a store to sell furs and other goods in what would become the Montana Territory two years later. Their venture was short- lived because Harkness was not suited for the arduous task of managing such an enterprise on the frontier; LaBarge, Harkness & Company disbanded and sold their wares to the American Fur Company, at Fort Benton in 1863.[46][47][48]

On April 30, John LaBarge, aboard the Shreveport, embarked northward for Fort Benton with 75 passengers aboard and all the cargo the vessel could carry. Two weeks later LaBarge, piloting the Emilie, set out, loaded with 160 passengers and 350 tons of freight, and in the process set speed and distance records. The Emilie completed its trip upriver, covering 2,300 miles (3,700 km) in thirty-two days.[49][lower-alpha 15] This was the first time LaBarge had been more than one hundred miles (160 km) above Fort Union.[46]

Some of the passengers were making the trip because of reports of gold in the Dakota and Washington territories. Several days before the two steamboats embarked, Harkness had gone ahead by railroad to Saint Joseph where he began recording the venture in his private journal. His first entry read:

St. Joseph, Mo., May 18, 1862. About one-third of this place has been burned and destroyed by the army. Took on ten passengers and left at 4 P.M. Weather very good. Made a good run. We are five hundred and seventy-five miles above St. Louis.

By June 17, with the Missouri River four feet (1.2 m) higher than ever known before, LaBarge and his partners decided to stop ten miles (16 km) above Fort Benton, where they built a trading post, naming it Fort LaBarge.[48][49]

Race with the Spread Eagle

LaBarge, Harkness & Co., and the American Fur Company, were fierce competitors in the fur trading business. In the spring of 1862 the two companies were about to make their annual trip up the Missouri River to Fort Benton with men and supplies. Each company, and their captains, were determined to get to the fort before the other. The Spread Eagle, owned by the American Fur Company, and commanded by Captain Bailey, departed Saint Louis first, two days before LaBarge departed in the Emilie, the faster of the two vessels. The Emilie soon caught up to the Spread Eagle at Fort Berthold at which point the journey turned into a frantic race. In an act of desperation, Bailey rammed LaBarge's boat, but after LaBarge threatened to resort to lethal force if Bailey did not cease, almost starting a shootout, the attempt was aborted. Regardless, LaBarge managed to bring his damaged boat to the fort four days before the Spread Eagle, which finally arrived on June 20. Bailey was soon held accountable for damages and reckless endangerment when he returned to Saint Louis, but LaBarge one month later pardoned him, allowing his reinstatement.[50][51][52][53][lower-alpha 16]

Custer's Campaign

Captain LaBarge also saw service in General Custer's campaign in 1876. In the autumn, when water levels on the upper Missouri River were low, a light-draft riverboat was needed, prompting the U.S. government to commission LaBarge and his steamboat, the John M. Chambers, to transport food and supplies to Fort Buford. LaBarge left Saint Louis on August 5 and reached Fort Buford on September 2. After the cargo was unloaded, Brigadier General Alfred Terry with a company of troops and an artillery piece were brought aboard. The steamboat started out for Wolf Point early on the morning of August 12, with the objective of heading off the Indians in that vicinity. LaBarge made about thirty miles (48 km) that day, making one stop at Fort Union to drop off General William Babcock Hazen and pick up a load of beef for the troops.[54]

On August 13, because of low water levels, LaBarge was only able to travel some twenty miles (32 km). The next day the party stopped to investigate a broken-down hospital ship abandoned on the shore, which was found to have been used by Major Marcus Reno's troops who were now pursuing the Indians. As they proceeded on, LaBarge came upon a small party coming down the river from Montana who brought news of Reno and his encounter with the Indians. The party boarded LaBarge's vessel and the next day made the return trip down the Missouri. On the 15th LaBarge arrived at Reno's camp. The Indians had already crossed the river, and Captain LaBarge immediately began the task of ferrying Reno's troops over, which was accomplished before nightfall. LaBarge then left for Buford the next morning, with General Terry, his staff, and 270 troops. LaBarge reached Fort Buford on August 17, and the John M. Chambers was discharged.[54]

Later life

After more than fifty years on the rivers, Captain LaBarge retired from steamboat piloting in 1885. By then steamboats could not compete with the ever emerging railroads. By 1866 there were only 71 steamboats in active service which could feasibly only service the river between Saint Louis and Kansas City. From 1890 to 1894 LaBarge worked for the city of Saint Louis. Thereafter he found employment with the federal government documenting steamboat wrecks that occurred on the Missouri River.[6][11]

Captain LaBarge managed to survive most of his associates involved with shipping and trade on the Missouri River, and was often consulted by historians and others who had occasion to recover accounts about people and events involved with the Missouri's early history.[55]

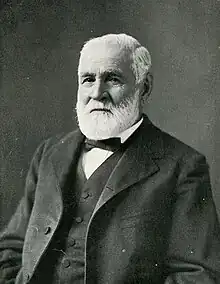

In 1896, LaBarge biographer Hiram M. Chittenden, an officer in the Army Corps of Engineers,[56] decided to publish an account of steamboat wrecks that occurred on the Missouri River in an attempt to determine which types of improvements for navigation were needed. Searching for information he sought out LaBarge, who was now retired, and who possessed an extensive and often first-hand knowledge of steamboat history from his many years of navigating on the Missouri River. Though LaBarge was willing to work at no cost, Chittenden hired him as his consultant and assistant. In the process, Chittenden soon discovered how knowledgeable and involved LaBarge was with Missouri River history overall and decided to do a biography about the man himself, asking him to compile his documents and correspondence and offer his personal recollections of his lifetime career as a riverman, trader and riverboat captain on the Missouri River. Work was moving along steadily until Chittenden was interrupted when he was called away during the Spanish–American War of 1898. While stationed in Huntsville, Alabama, Chittenden received news in 1899 from Saint Louis that LaBarge had taken ill and was dying. He immediately telegraphed LaBarge's son asking him to assure LaBarge that "...I shall faithfully finish his work. It will take me a long time, but I shall not fail to do it." Chittenden's pledge reached LaBarge, who had been suffering from a tumor on his neck, just before he died one and a half hours later,[57] after an unsuccessful surgery, from blood poisoning on April 3, 1899, in Saint Louis. LaBarge was 83.[6][11] Four years later, in 1903, Chittenden completed and published his two-volume biography of LaBarge and his life on the Missouri River.[58] In Volume II of his work he quotes LaBarge expressing his love of the Missouri River.

I had no desire to go on any other river. The Missouri was my home. I had grown up on it from childhood. I liked it, and knew I could not feel at home on any other.[59]

A natural and prominent rock formation rising 150 feet (46 m) above the Missouri River in Chouteau County, Montana, was named LaBarge Rock, is his honor.[6][11]

On Thursday morning, April 6, LaBarge's funeral was held at Saint Francis Xavier Cathedral in Saint Louis, and drew a large gathering. Attending Jesuits expressed their gratitude to LaBarge who, throughout his career, had offered his steamboat services to their missionary efforts, at no cost. A solemn high mass was held by Archbishop Kain,[lower-alpha 17] who was assisted by eight priests. Six of LaBarge's grandsons acted as pall bearers. Father Walter H. Hill, a lifelong friend of LaBarge, gave the final funeral sermon, expressing that LaBarge had led a good life and that no stigma or vice could be attached to his name. He was buried in his home state of Missouri in Calvary Cemetery near the Missouri River.[60] In 2002, Joseph LaBarge was inducted into the National Rivers Hall of Fame, sponsored by The National Mississippi River Museum, as "The most renowned mountain boat pilot on the upper Missouri River."[19]

See also

- Manuel Lisa, merchant, fur trader, led the first trading expedition to the upper Missouri River in 1807

- Grant Marsh, notable fur trader of the far west during LaBarge's day

- North American fur trade

- Pacific Fur Company

- Rocky Mountain Fur Company

- Walk-in-the-water (steamboat) and Ontario (steamboat), first steamboats to run on the Great Lakes

Notes

- ↑ Often spelled as La Barge[1]

- ↑ Sometimes spelled as Emily[2]

- ↑ LaBarge's brother, Charles, would later lose his life in a steamboat explosion in 1852 aboard the Saluda. His other brother, John, became a partner with Joseph and piloted a steamship owned by their company.[7]

- ↑ In 1886 Baden became a part of St. Louis proper.

- ↑ Founded in 1808 by John Jacob Astor

- ↑ Some accounts spell the steamboat's name with two words, i.e. Yellow Stone.[17]

- ↑ Established in 1832, Fort Pierre was a major trading post and military outpost on the Missouri River in what is now central South Dakota.

- ↑ 1833 was the year in which cholera made its first appearance in the United States.[20]

- ↑ The most important member of the crew was the pilot, whose performance was crucial to the safety of the crew and steamboat, and who was paid in accordance with such responsibility. Pilots were paid up to $1200 per month; captain's pay averaged $200 per month.[21]

- ↑ A new side-wheeler steamer with a capacity of 180 tons[13]

- ↑ Established by the Upper Missouri Outfit of the American Fur Company in 1823.[28]

- ↑ Hoecken died of cholera on this voyage.[32]

- ↑ The river past Fort Benton to the Great Falls was considered the farthest navigable region on the river.[39]

- ↑ The average steamboat only carried 200 to 300 tons.[40]

- ↑ On the return trip, going down-stream, the Emilie made it to Saint Louis in fifteen days. Her speed going up-stream averaged 71 miles (114 km) a day-speed going down-stream averaged 152 miles (245 km) per day.[49]

- ↑ LaBarge's close friend, Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, was also aboard the Spread Eagle during the race.[51]

- ↑ Kain (1841–1903), a Roman Catholic priest who served as the Archbishop of Saint Louis, was the first native-born American to hold that office.

Citations

- ↑ Chitteden, 1903, vol 1, title page

- 1 2 Sunder, 1965, p. 234

- ↑ Chitteden, 1903, vol 1, p. 13

- ↑ Chitteden, 1903, vol 1, p. 4

- 1 2 Missouri Historical Review, 1969, p. 449

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Harper, Historical Society of Missouri, 2019, essay

- ↑ Chitteden, 1903, vol. 1, p. 124

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Vol I, pp. 13–15

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Vol I, pp. 13–15, 18–19

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol 1, p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 5 LaBarge, 2019, essay

- ↑ Chitteden, 1903, vol 1, pp. 71–72

- 1 2 3 LaBarge Family website

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I1, p. 444

- 1 2 Chittenden, 1903, vol I, p. 133

- ↑ Martin (ed), 1906, pp. 282–283

- ↑ Jackson, 1985, Cover page, etc.

- ↑ Missouri Historical Review, 1969, p. 450

- 1 2 The National Mississippi River Museum

- 1 2 Chappell, 1911, p. 76

- ↑ Pacific Northwest Quarterly, April 1949 Vol.40, Issue 2, p. 96

- ↑ Jackson, 1985, p. 102

- ↑ Missouri Historical Review, 1969, p. 452

- ↑ Jackson, 1985, pp. 101–102

- 1 2 Chappell, 1911, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, pp. 32–34

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, pp. 177–181

- ↑ National Park Service

- ↑ Thompson, 1986, p. 61

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, p. 54

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, pp. 193–194

- 1 2 Missouri Historical Review, 1969, p. 456

- ↑ Chittenden, 1905, Vol. II, p. 62

- ↑ Missouri Historical Review, 1969, pp. 456–457

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, pp. 200–201

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, p. 199

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, p. 53

- 1 2 Chittenden, 1903, Volume I, pp. 217-218

- ↑ O'Neil, 1975, p. 14

- 1 2 3 Missouri Historical Review, 1969, p. 459

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol I, pp. 240–241

- ↑ Missouri Historical Review, 1969, pp. 458–459

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Vol. I, pp. 241–242

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Vol. I, p. 247

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, vol II, pp. 255–256

- 1 2 3 Chittenden, 1903, vol II, p. 287–288

- ↑ Thompson, F. M., 2004, p. 259

- 1 2 Historical Society of Montana: Diary of James Harkness, 1896, p. 343

- 1 2 3 Missouri Historical Review, 1969, pp. 459–460

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Vol. II, pp. 290–291

- 1 2 Chittenden, 1905, Vol. II, p. 778

- ↑ Barbour, 2001, p. 194

- ↑ O'Neil, 1975, p. 30

- 1 2 Chittenden, 1903, Volume 2, pp. 390-392

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Volumes I, p. 439

- ↑ Caldbick, 2017, Essay

- ↑ Dobbs, 2015, p. 87

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Volumes I & II, title pages

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Volume 2, p. 426

- ↑ Chittenden, 1903, Volume II, pp. 440–442

Bibliography

- Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Vol. I. Bismarck, N.D, Tribune, State Printers and Binders. 1906.

- Atkins, C. J., ed. (1908). Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Vol II: Log of Steamer Robert Campbell, Jr., From Saint Louis to Fort Benton, Montana Territory. Bismarck, N.D, Tribune, State Printers and Binders. pp. 267–284.

- Barbour, Barton H. (2001). Fort Union and the Upper Missouri Fur Trade. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3295-2.

- Bowdern, T. S. (July 1968). "Joseph LaBarge Steamboat Captain". Missouri Historical Review. The State Historical Society of Missouri. 62 (4): 449–470. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Chappell, Phillip Edward (1911). A history of the Missouri River. Kansas City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chittenden, Hiram Martin (1903). History of early steamboat navigation on the Missouri River: life and adventures of Joseph La Barge, Volume I. New York: Francis P. Harper.

- —— (1903). History of early steamboat navigation on the Missouri River: life and adventures of Joseph La Barge, Volume II. New York: Francis P. Harper.

- —— (1902). The American fur trade of the far West, Volume I. New York: Francis P. Harper.

- —— (1902). The American fur trade of the far West Volume 2. New York: Francis P. Harper.

- —— (1902). The American fur trade of the far West Volume 3. New York: Francis P. Harper.

- ——; de Smet, Pierre-Jean; Richardson, Alfred Talbot (1905). Life, letters and travels of Father Pierre-Jean de Smet, S.J., 1801–1873, Volume I. New York: Francis P. Harper.

- ——; de Smet, Pierre-Jean; Richardson, Alfred Talbot (1905). Life, letters and travels of Father Pierre-Jean de Smet, S.J., 1801–1873, Volume II. New York: Francis P. Harper.

- Dobbs, Gordon B. (2015). Hiram Martin Chittenden: His Public Career. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-6275-1.

- Jackson, Donald Dean (1985). Voyages of the Steamboat Yellow Stone. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 978-0-8991-9306-9.

- Martin, G. W., ed. (1906) [1875]. Collections of the Kansas state historical society, Vol IX. Topeka, Kansas: State Printing Office.

- O'Neil, Paul (1975). The Riverman. Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-1496-3. (Also in PDF format.)

- Oviatt, Alton B. (April 1949). "Steamboat Traffic on the Upper Missouri River, 1859–1869". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. University of Washington. 40 (2): 93–105. JSTOR 40486826.

- Sunder, John E. (1993) [1965]. The Fur Trade on the Upper Missouri, 1840–1865. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2566-4.

- Thompson, Erwin N. (1986). Fort Union Trading Post: fur trade empire on the upper Missouri. Theodore Roosevelt Nature and History Association. ISBN 9780960165223.

- Thompson, Francis McGee (2004). A Tenderfoot in Montana: Reminiscences of the Gold Rush, the Vigilantes, and the Birth of Montana Territory. Montana Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9721-5222-8.

- Harkness, James (1896). Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana, Vol. II: Diary of James Harkness, of the firm of LaBarge, Harkness and Company. Helena, Montana: Rocky Mountain Publishing Co. pp. 343–361.

Online sources

- Caldbick, John (2017). "Chittenden, Hiram Martin (1858–1917)". The State of Washington, HistoryLink.org. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- LaBarge, Craig A. "Captain Joseph LaBarge (1815–1899)". RootsWeb/Ancestry.com. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- Harper, Kimberly. "Joseph Marie LaBarge". The State Historical Society of Missouri. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- "Steamboat Captain's Wife: A Brief Biography of Pelagie Guerette La Barge" (PDF). www.laberge.info.

- "National Rivers Hall of Fame Inductees". The National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium. 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

Further reading

- Boller, Henry A (1868). Among the Indians. Philadelphia: T. Ellwood Zell.

- Gillespie, Michael (2000). Wild River, Wooden Boats: True Stories of Steamboating and the Missouri River. Heritage Press. ISBN 978-0-9620-8237-5.

- Jackson, Donald (1987) [1985]. Voyages of the Steamboat Yellow Stone. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806120362. OCLC 16095625.

- Lass, William E. (2008). Navigating the Missouri: Steamboating on Nature's Highway, 1819–1935. Norman, Okla.: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 9780870623554. OCLC 680583734.

- Potter, Tracy (2017). Steamboats in Dakota Territory: Transforming the Northern Plains. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6258-5763-7.

- Sorensen, Lola. LaBarge Family Lines: Including Gueret, Lauck, Bequet, Dodier, Lindsey Related Lines. OCLC 865852484. Call number 929.273 L111s. Manuscript prepared for Pierre L. LaBarge and donated to the Family History Library, Salt Lake City.