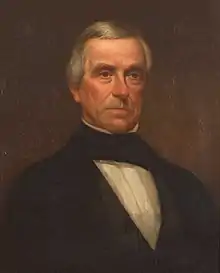

Joseph Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 32nd Governor of Virginia | |

| In office January 16, 1852 – January 1, 1856 | |

| Lieutenant | Shelton Leake |

| Preceded by | John B. Floyd |

| Succeeded by | Henry A. Wise |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 14th district | |

| In office March 4, 1845 – March 3, 1847 | |

| Preceded by | George W. Summers |

| Succeeded by | Robert A. Thompson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 20th district | |

| In office March 4, 1835 – March 3, 1841 | |

| Preceded by | John J. Allen |

| Succeeded by | Samuel L. Hays |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 18th district | |

| In office March 4, 1823 – March 3, 1827 | |

| Preceded by | Mark Alexander |

| Succeeded by | Isaac Leffler |

| In office January 21, 1833 – March 3, 1833 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Doddridge |

| Succeeded by | John H. Fulton |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates | |

| In office 1815-1816 1818-1822 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 19, 1785 Orange County, New York |

| Died | February 27, 1877 (aged 91) Bridgeport, West Virginia |

| Political party | Jacksonian democrat, Democrat |

| Occupation | Military officer, farmer, politician |

Joseph Ellis Johnson (December 19, 1785 – February 27, 1877) was a farmer, businessman, and politician who served as United States Representative and became the 32nd Governor of Virginia from 1852 to 1856, the first Virginia governor to be popularly elected as well as the only Virginia governor from west of the Appalachian mountains.[1] During the American Civil War, he sympathized with the Confederacy, but returned to what had become West Virginia for his final years.[2]

Early life and family

Born in Orange County, New York, Johnson moved with his widowed mother Abigail Wright Johnson (1753-1839) and four siblings to Belvidere, New Jersey in 1791, and then to Winchester, Virginia (possibly after a long detour to Suffolk in southeast Virginia).[3] In 1801, the family moved further west across the Appalachian Mountains to Bridgeport in what became Harrison County, Virginia (and West Virginia late in his lifetime, as discussed below).[4]

The sixteen-year-old Johnson soon got a job helping Ephraim Smith, a local gentleman farmer suffering from ill health, and managed Smith's land. Three years later, on May 14, 1804, he married one of his employer's daughters, Sarah Smith (1784-1853). At least five of their children died before the age of 11.[5] However, their son Dr. Benjamin Franklin Johnson (1816-1855) and daughter Catherine Selina Minor (1824-1900) survived and married, although both moved from the area (to Franklin County, Ohio, and Baltimore, respectively).

Career

By 1807, in addition to farming, Johnson rebuilt the Smith mill (built circa 1803) on Simpson Creek, which he bought from Smith's widow and heirs.[6] In 1811, the Harrison county government ordered a bridge built about a quarter mile above "Johnson's Mill", which became the first bridge built in Harrison county outside Clarksburg.[7] As discussed below, Johnson would incorporate Bridgeport on his land, as well as build a mansion, which survives today as the Governor Joseph Johnson House, although both his son and daughter moved to states which remained in the Union.[8]

Unlike many Virginians living across the Appalachian mountains, Johnson came to own enslaved people. While Johnson did not own slaves according to the 1820 federal census,[9] in both the 1830 and 1840 federal census, Johnson owned three enslaved males and three enslaved females (two of each were children in 1830 but by 1840 all were 10 years old or older).[10][11] In the 1850 federal census, the first with separate slave schedules, Johnson owned two mulatto men (aged 50 and 22), as well as a 15 year old Black boy, and three Black women (aged 48, 25 and 23 years old).[12] A decade later, in the last federal slave census, Johnson owned 11 enslaved people (mulatto men aged 65, 35 and 29 years old, mulatto women aged 60, 33 and 31, a 15 year old Black boy, and mulatto boys aged 8, 6, 3 and year old).[13]

Constable to Captain

Johnson initially became active in local politics as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party (aligned with President Thomas Jefferson). He became the local constable in 1811 and formed one of two or three companies of "Harrison riflemen" that fought the War of 1812. In 1814, Captain Johnson and Captain John McWhorter of the other company led their riflemen to Norfolk, where Johnson and his men helped keep the peace until the war's end in 1815, while McWhorter's men headed west under General (and future President) William H. Harrison to fight in Ohio. Johnson's men were first assigned to the Sixth Regiment of Virginia militia, then to the Fourth Regiment.[14]

Delegate to Congressman and constitutional convention delegate

When Johnson returned to Harrison County, voters elected him to represent them in the Virginia House of Delegates, rejecting incumbent John Prunty, who had represented them for 22 years.[15] One of Johnson's first acts was introducing legislation organizing Bridgeport as a town (on 15 acres of his land). That act passed on January 15, 1816; Johnson became one of the town's seven original trustees. Voters reelected Johnson to the House of Delegates in 1816 and with a year's gap, elected and reelected him again in 1818-1822, after which Johnson decided not to run again. Johnson would build a mansion in Bridgeport, the Governor Joseph Johnson House.[16]

At the urging of Judge John G. Jackson, Johnson ran against prominent orator and Congressman Philip Doddridge, Johnson again upset the incumbent. He served in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Congresses (March 4, 1823 – March 3, 1825, and became chair of the Committee on Expenditures on Public Buildings in the Nineteenth Congress. Johnson lost his reelection campaign in 1826 to Doddridge and so did not serve in the Twentieth nor Twenty-first Congress, but when Doddridge died, voters elected Johnson to the Twenty-second Congress to fill the brief vacancy, so Johnson again served from January 21 to March 3, 1833. Johnson did not run for renomination in 1832. During this period, Congress built and maintained the National Road westward from Cumberland, Maryland; Johnson sat on the Cumberland Road committee.[17] A key question became where the road would cross the Ohio River. Although Wheeling became the crossing point, others had advocated Parkersburg as the crossing point, following what would later become the Northwestern Turnpike (now U.S. Route 50) through Romney and Clarksburg to Parkersburg. Part of the compromise that allowed the Wheeling route was the construction of a road between Wheeling and Romney.

Johnson again ran for Congress as a Jacksonian in 1834, won the seat in the Twenty-fourth Congress, and was reelected (as a Democrat) to the Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Congresses (March 4, 1835 – March 3, 1841). Johnson became chair of the Committee on Accounts in the Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Congresses. He declined to run for renomination in 1840 but was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1844. Johnson was elected to the Twenty-ninth Congress (March 4, 1845 - March 3, 1847) and became chair of the Committee on Revolutionary Claims (Twenty-ninth Congress). He again declined to run for renomination in 1846.[18]

In 1847, Johnson again ran for election to the Virginia House of Delegates and was reelected the following year, again serving part-time while pursuing his farming and other business interests. During the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850 and 1851, Johnson was one of the four delegates from the west-of-the-Appalachians district consisting of Wood, Ritchie, Harrison, Doddridge, Tyler, and Wetzel Counties, alongside John F. Snodgrass, Gideon D. Camden and Peter G. Van Winkle. As the convention's eldest delegate, Johnson called the convention to order and chaired the suffrage committee, where he fought for his region's interests, especially universal adult white male suffrage and against a poll tax.[19]

Governor of Virginia

The General Assembly elected Johnson Governor of Virginia in 1851, shortly before the new state constitution made the office elective by voters. Johnson thus served a short initial term. He also became the Democratic Party's candidate in September 1851, then won reelection by defeating the Whig candidate (also from west of the Appalachians), George W. Summers, in part because Summers supported the American Colonization Society and thus was considered too "light-handed on the issue of slavery".[20]

The only Virginia governor from west of the Allegheny Mountains began his gubernatorial duties under the new constitution on January 1, 1852. He served four years before returning to his Bridgeport home, although his wife died and was buried in Bridgeport during his governorship.[21] As governor (and prohibited by the constitution from succeeding himself), Johnson granted clemency (sale out of state) to three enslaved people convicted for murders in and near Richmond in highly publicized cases. Phillis had been convicted of murdering a crying child under her care by administering morphine; Jordan Hatcher had killed a white overseer in a Richmond tobacco factory who was whipping him; young Lucy had attempted to conceal a pregnancy and ingested laudanum and camphor while giving birth in an outbuilding and the infant's corpse was later found.[22]

American Civil War

Johnson had been a Democratic presidential elector in 1860 and personally disfavored secession. However, during Virginia's secession crisis in 1861, Johnson joined in the Confederate States' declared secession, and became an elector for Jefferson Davis as the Confederate President.[23] Pro-Union men held a mass meeting in Clarksburg on April 22, 1861, to hear an address by John S. Carlile, and another on May 3, 1861, to hear an address by Francis H. Pierpont. However, Johnson countered by chairing another meeting on April 26 of "Southern Rights" men, including W.P. Cooper, Norval Lewis, and W. F. Gordon.[24][25]

When U.S. Army soldiers occupied Bridgeport, Johnson moved his household eastward across the Appalachians to Staunton, where he remained for the rest of the war, during which the State of West Virginia was created, in part through Carlile's and Pierpont's efforts. His nephew, Waldo P. Johnson, who had become a lawyer in Harrison County before moving to Missouri in 1842 (where he served in that state's legislature and then became a U.S. Senator and member of the Peace convention of 1861), was expelled from the U.S. Senate on January 10, 1862, whereupon he became a Confederate Senator from Missouri and (after a time in Canada following the Confederacy's defeat), in 1875 chairman of Missouri's constitutional convention.

Final years, death and legacy

In 1866, Johnson, who had returned to Bridgeport after the conflict, formally joined the Simpson Creek Baptist Church, in whose churchyard his wife had been buried 13 years before. He died at his home, Oakdale, in Bridgeport in 1877 and was buried beside his wife and young children in the old Brick Church Cemetery. In 1887, a decade after Johnson's death, West Virginia's legislature formally incorporated Bridgeport. In 1941, the cemetery merged with the adjoining Odd Fellows cemetery and Masonic Lodge cemetery and became known as the "Bridgeport Cemetery".[26] Several locations in Bridgeport, West Virginia honor Johnson, including Johnson Avenue, Johnson Elementary School, and his former home, the Governor Joseph Johnson House.

The Library of Virginia maintains his executive papers.[27]

Electoral history

1851; Johnson was elected Governor of Virginia with 53% of the vote, defeating Whig George W. Summers.

References

- ↑ Dorothy Davis, History of Harrison County West Virginia (Clarksburg, WV; American Association of University Women, 1970, corrected 1972) p. 343

- ↑ Louis H. Manarin, "Joseph Johnson" in West Virginia Encyclopedia, available at https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1041

- ↑ Davis, p. 343

- ↑ West Virginia bio

- ↑ Davis, p. 415

- ↑ West Virginia Bio

- ↑ Davis, p. 343

- ↑ Davis, pp. 344-345

- ↑ 1820 U.S. Federal Census for Harrison County, Virginia p. 18 of 30 on ancestry.com

- ↑ 1830 U.S. Federal Census for Harrison County, Virginia pp. 33-34 of 60.

- ↑ 1840 U.S. Federal Census for Harrison County, Virginia pp. 133-134 of 201.

- ↑ 1850 U.S. Federal Census Slave Schedule for Harrison County, Virginia district 21 p. 3 of 5

- ↑ 1860 U.S. Federal Census Slave Schedule for Harrison County, Virginia p. 5 of 8 on ancestry.com

- ↑ Davis, p. 344

- ↑ George W. Atkinson and Alvaro Gibbens, Prominent men of West Virginia: p.210, available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044086417680&view=1up&seq=232

- ↑ Davis, pp. 344-345

- ↑

- United States Congress. "Joseph Johnson (id: J000155)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ↑

- United States Congress. "Joseph Johnson (id: J000155)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ↑ West Virginia bio

- ↑ Tamika Y. Nunley, The Demands of Justice: Enslaved Women, Capital Crime & Clemency in Early Virginia (University of North Carolina Press 2023 ISBN 978-1-4696-7311-0) p. 77

- ↑ Davis, p. 346.

- ↑ Nunley pp. 75-82, 134-135

- ↑ West Virginia bio

- ↑ Davis, pp. 183-185.

- ↑ Haymond, Henry, History of Harrison County, West Virginia : from the Early Days of Northwestern Virginia to the Present, Acme Publishing Co., Morgantown, WV, 1910, pgs. 335-336

- ↑ Davis, pp. 346, 417

- ↑ A Guide to the Executive Papers of Governor Joseph Johnson, 1852-1855