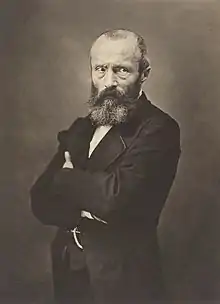

Johannes Vermeer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 1632 |

| Died | December 1675 (aged 42–43) Delft, Holland, Dutch Republic |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | 34 works universally attributed[2] |

| Movement | Dutch Golden Age Baroque |

Johannes Vermeer (October 1632 – December 1675) was a Dutch Baroque Period[3] painter who specialized in domestic interior scenes of middle class life. His works have been a common theme in literature and films in popular culture since the rediscovery of his works by 20th century art scholars.

He was recognized during his lifetime in Delft and The Hague, but his modest celebrity gave way to obscurity after his death. He was barely mentioned in Arnold Houbraken's major source book on 17th-century Dutch painting (Grand Theatre of Dutch Painters and Women Artists), and was thus omitted from subsequent surveys of Dutch art for nearly two centuries.[4][5] In the 19th century, Vermeer was rediscovered by Gustav Friedrich Waagen and Théophile Thoré-Bürger, who published an essay attributing 66 pictures to him, although only 34 paintings are universally attributed to him today.[2] Since that time, Vermeer's reputation has grown, and he is now acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Like some major Dutch Golden Age artists such as Frans Hals and Rembrandt, Vermeer never went abroad. Similar to Rembrandt, he was an avid art collector and dealer.

Rediscovery in the 20th century

Vermeer's works were largely overlooked by art historians for two centuries after his death. A select number of connoisseurs in the Netherlands did appreciate his work, yet even so, many of his works were attributed to better-known artists such as Metsu or Mieris. The Delft master's modern rediscovery began about 1860, when German museum director Gustav Waagen saw The Art of Painting in the Czernin gallery in Vienna and recognized the work as a Vermeer, though it was attributed to Pieter de Hooch at that time.[6] Research by Théophile Thoré-Bürger culminated in the publication of his catalogue raisonné of Vermeer's works in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1866.[7] Thoré-Bürger's catalogue drew international attention to Vermeer[8] and listed more than 70 works by him, including many that he regarded as uncertain.[7] The accepted number of Vermeer's paintings today is 34.

Upon the rediscovery of Vermeer's work, several prominent Dutch artists modelled their style on his work, including Simon Duiker. Other artists who were inspired by Vermeer include Danish painter Wilhelm Hammershoi[9] and American Thomas Wilmer Dewing.[10] In the 20th century, Vermeer's admirers included Salvador Dalí, who painted his own version of The Lacemaker (on commission from collector Robert Lehman) and pitted large copies of the original against a rhinoceros in some surrealist experiments. Dali also immortalized the Dutch Master in The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table, 1934.

Han van Meegeren was a 20th-century Dutch painter who worked in the classical tradition. He became a master forger, motivated by a blend of aesthetic and financial reasons, creating and selling many new "Vermeers" before being caught and tried.[11]

On the evening of 23 September 1971, a 21-year-old hotel waiter, Mario Pierre Roymans, stole Vermeer's Love Letter from the Fine Arts Palace in Brussels where it was on loan from the Rijksmuseum as a part of the Rembrandt and his Age exhibition.[12]

In popular culture

In Proust's novel In Search of Lost Time, the connoisseur Charles Swann is depicted as playing a leading role in rediscovering Vermeer. The writer Bergotte also greatly admires the painter, and, at the moment of his death, Bergotte has a vision of artistic meaning while looking at a detail of Vermeer's View of Delft:

- His dizziness increased; he fixed his gaze, like a child upon a yellow butterfly that it wants to catch, on the precious patch of wall. "That's how I ought to have written," he said. "My last books are too dry, I ought to have gone over them with a few layers of colour, made my language precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall....." In a celestial pair of scales there appeared to him, weighing down one of the pans, his own life, while the other contained the little patch of wall so beautifully painted in yellow. He felt that he had rashly sacrificed the former for the latter.... A fresh attack struck him down.... He was dead.

A Vermeer painting plays a key part of the dénouement in Agatha Christie's After the Funeral (1953). Susan Vreeland's novel Girl in Hyacinth Blue follows eight individuals with a relationship to a painting of Vermeer. The young adult novel Chasing Vermeer by Blue Balliett centers on the fictional theft of Vermeer's A Lady Writing. J. P. Smith's novel The Discovery of Light deals largely with Vermeer. The character of Barney in Thomas Harris's novel Hannibal (1999) has a goal to see every Vermeer painting in the world before he dies.

In 1978 the American science fiction author Gordon Eklund published a short story "Vermeer's Window" in the magazine Universe 8, about an aspiring artist who is given the ability to reproduce Vermeer's works.

In a scene in the 1981 film Arthur, starring Dudley Moore, Arthur's grandmother opens a Vermeer painting that she has just purchased. In the film, the grandmother calls the painting Woman Admiring Pearls, but it is actually called Woman with a Pearl Necklace.

Peter Greenaway's film A Zed & Two Noughts (1985) features an orthopedic surgeon named Van Meegeren who stages highly exact scenes from Vermeer paintings in order to paint copies of them.

John Jost's film All the Vermeers in New York (1990) makes reference to a woman's resemblance to a Vermeer painting.

Dutch composer Louis Andriessen based his opera Writing to Vermeer (1997–98, libretto by Peter Greenaway) on the domestic life of Vermeer.

Brian Howell's novel The Dance of Geometry (2004) narrates four interlinking episodes that centre around the creation of Vermeer's The Music Lesson, dealing with his childhood and courtship of his wife-to-be, a visit by a French traveller who becomes involved in the final stages of the work and its tragic end, a modern copyist's deliberations on the importance of the work in his life, and the final stages of Vermeer's life.

Tracy Chevalier's novel Girl with a Pearl Earring (1999), and the 2003 film of the same name, present a fictional account of Vermeer's creation of the famous painting and his relationship with the equally fictional model. The film was nominated for Oscars in cinematography, art direction, and costume design.[13]

Vermeer in Bosnia (2004) is a collection of essays by Lawrence Weschler. The title essay is a meditation on the relationship between Vermeer's paintings in the Mauritshuis in The Hague and the events being recounted in the Yugoslav War Crimes Tribunal in the same city.

The song "No One Was Like Vermeer" from the 2008 album Because Her Beauty Is Raw and Wild by Boston singer-songwriter Jonathan Richman pays tribute to Vermeer's painstaking technique. Richman also references Vermeer in his song "Vincent Van Gogh" and both songs are frequently part of Richman's live performances.

Historian Timothy Brook's Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World (2007) examines six of Vermeer's paintings for evidence of world trade and globalization during the Dutch Golden Age.

"Jan Vermeer" is a rockabilly song written by Bob Walkenhorst for his solo album The Beginner. David Olney's song "Mister Vermeer" on his 2010 album Dutchman's Curve imagines Vermeer's unrequited love for the subject of Girl with a Pearl Earring.

The 2013 documentary film Tim's Vermeer follows inventor Tim Jenison's examination on his theory that Vermeer used optical devices to assist in generating his realistic images.[14]

In late 2020, chip designer AMD released desktop microprocessors based on Zen 3 microarchitecture, codenamed "Vermeer" to honor Vermeer's beautiful art legacy.

References

- ↑ "The Procuress: Evidence for a Vermeer Self-Portrait". Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- 1 2 Jonathan Janson, Essential Vermeer: complete Vermeer catalogue; accessed 16 June 2010.

- ↑ Jennifer Courtney & Courtney Sanford: "Marvelous To Behold" Classical Conversations (2018)

- ↑ Barker, Emma; et al. (1999). The Changing Status of the Artist. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 199. ISBN 0-300-07740-8.

- ↑ Vermeer was largely unknown to the general public, but his reputation in popular culture was not totally eclipsed after his death: "While it is true that he did not achieve widespread fame until the 19th century, his work had always been valued and admired by well-informed connoisseurs." Blankert, Albert, et al. Vermeer and his Public, p. 164. New York: Overlook, 2007, ISBN 978-1-58567-979-9

- ↑ Gaskell, Jonker & National Gallery of Art (1998). Vermeer Studies, pp. 19–20.

- 1 2 Gaskell, Jonker & National Gallery of Art (1998). Vermeer Studies, p. 42.

- ↑ Vermeer, J., F. J. Duparc, A. K. Wheelock, Mauritshuis (Hague, Netherlands), & National Gallery of Art (1995). Johannes Vermeer. Washington: National Gallery of Art, p. 59. ISBN 0-300-06558-2

- ↑ Gunnarsson, Torsten (1998), Nordic Landscape Painting in the Nineteenth Century. Yale University Press, p. 227. ISBN 0-300-07041-1

- ↑ "Interpretive Resource: Artist Biography: Thomas Wilmer Dewing". Artic.edu. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Anthony Julius (22 June 2008). "The Lying Dutchman". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ Janson, Jonathan. "Vermeer Thefts: The Love Letter". www.essentialvermeer.com. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003) Awards". IMDb.com. 10 January 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ↑ "Triangulation 118". Twit.Tv. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

Further reading

- Liedtke, Walter (2009). The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-344-9.

- Liedtke, Walter A. (2001). Vermeer and the Delft School. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-973-4.

- Kreuger, Frederik H. (2007). New Vermeer, Life and Work of Han van Meegeren. Rijswijk: Quantes. pp. 54, 218 and 220 give examples of Van Meegeren fakes that were removed from their museum walls. Pages 220/221 give an example of a non-Van Meegeren fake attributed to him. ISBN 978-90-5959-047-2. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- Singh, Iona (2012). "Vermeer, Materialism and the Transcendental in Art". from the book, Color, Facture, Art & Design. United Kingdom: Zero Books. pp. 18–40.

- Schneider, Nobert (1993). Vermeer. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag. ISBN 3-8228-6377-7.

- Sheldon, Libby; Nicola Costaros (February 2006). "Johannes Vermeer's 'Young woman seated at a virginal". The Burlington Magazine (vol. CXLVIII ed.) (1235).

- Snyder, Laura J. (2015). Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-07746-9.

- Steadman, Philip (2002). Vermeer's Camera, the truth behind the masterpieces. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280302-6.

- Wadum, J. (1998). "Contours of Vermeer". In I. Gaskel and M. Jonker (ed.). Vermeer Studies. Studies in the History of Art. Washington/New Haven: Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers XXXIII. pp. 201–223.

- Wheelock, Arthur K. Jr. (1988) [1st. Pub. 1981]. Jan Vermeer. New York: Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-1737-8.

External links

| Library resources about Johannes Vermeer in popular culture |

- 500 pages on Vermeer and Delft

- Johannes Vermeer, biography at Artble

- Essential Vermeer, website dedicated to Johannes Vermeer

- Johannes Vermeer in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Vermeer Center Delft, center with tours about Vermeer

- Vermeer's Mania for Maps, WGBHForum, 30 December 2016

- Pigment analyses of many of Vermeer's paintings at Colourlex

- Location of Vermeer's The Little Street Archived 15 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine