| Joanna Visconti | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judge/Queen of Gallura | |||||

| Reign | 1296-1308 (de facto) 1308-1339 (titular) | ||||

| Predecessor | Nino | ||||

| Born | 1291 Gallura, Sardinia | ||||

| Died | August 1339 (aged 47–48) Florence | ||||

| Spouse | Rizzardo IV da Camino, Lord of Treviso | ||||

| |||||

| House | Visconti (Sardinia branch) | ||||

| Father | Nino, King of Gallura | ||||

| Mother | Beatrice d'Este | ||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||

Joanna of Gallura (..., c. 1291 – Florence, 1339), also known as Giovanna Visconti, was the last titular Judge (giudicessa) of Gallura. Joanna claimed her rights in Sardinia to no avail and eventually sold them to her relatives, the Visconti of Milan, who later sold them to the Crown of Aragon. She is mentioned passingly by Dante Alighieri in the Divine Comedy. Her father, a friend of Dante's, but consigned to Purgatory with the other negligent rulers, asks her to be reminded of him.

Biography

Early life

The Visconti of Pisa were present in Pisa since at least since the tenth century and since then had produced a lineage of influential Pisan politicians. In 1205, Lamberto Visconti married Elena of Gallura and became the first Visconti to be the Judge of Gallura. He was succeeded, in order, by Ubaldo, Ubaldo II, John, and Ugolino Visconti.

Joanna was the daughter of Ugolino (also known as Nino) and Beatrice, daughter of Obizzo II d'Este. Upon Nino's death in 1296, Joanna became the last Judge of Gallura.[1] She succeeded her father when she was a baby, though her succession was purely nominal. Not long after her father's death, the Republic of Pisa, affiliated with the Ghibellines, took most of her inheritance.[2] Nino had been a notable Guelph leader who had served as podestà in Pisa until his exile in 1288, during which he aligned with known Pisan enemies Florence and Lucca and led a campaign against Pisa.[3]

In 1296, Pope Boniface VIII assigned Joanna as a ward to Volterra, where she and her mother would live for a few years. In that time, Beatrice became engaged to a son of Alberto Scotto, lord of Piacenza. Galeazzo I Visconti of Milan, desperate for an alliance with the Este family, had been able to circumvent the engagement and instead married Beatrice in 1300. This marriage outraged the Torriani family. With the help of Scotto, they drove the Visconti out of Milan. Galeazzo would then live in Tuscany until his death, but Beatrice was able to eventually return to Milan.[4]

Marriage

Though Pisa had taken most of her inheritance, Joanna remained in possession of great political power because of her title as Judge of Gallura and her parents' noble lineages. In adolescence, her political position and her beauty drew many suitors whose families sought power in Sardinia.

Joanna's first suitor was the son of the Genoese noble Bernabò Doria; a marriage with him would have promoted the union of Genoa and Pisa against the Crown of Aragon. Then, a second option became the nephew of the Count of Donaratico, Tedice della Gherardesca; the possibility of his marriage to Joanna polarized the Pisans, causing civil conflict. Finally, the Tuscan Guelphs recommended that Joanna marry Corradino Malaspina, whose family already owned many valuable assets in Sardinia. Corradino's marriage with Joanna would only further expand their wealth and territory.[5] James II of Aragon also had a stake in Joanna's hand for marriage, as he wanted her to marry an Aragonese nobleman because it would aid his plan of conquering Sardinia while minimizing military costs.[6]

Despite their desperate clamor for Joanna, none of the above noblemen married her. In 1308, Joanna married Rizzardo IV da Camino, Count of Ceneda and Lord of Treviso.[5] Only four years after their marriage, Rizzardo was assassinated in a plan by Alteniero degli Azzoni, whose wife Rizzardo had seduced.[7] The exact details of the assassination are unclear. According to the Ottimo Commento, Cangrande della Scala may have been involved in the plan. According to Benvenuto da Imola, another early commentator of the Divine Comedy, Guecello, Rizzardo's brother, may have been coveting Rizzardo's power and also abetted his assassination. After Rizzardo's death, Guecello promptly took over the position of Lord of Treviso.[7]

Later years

From 1323 until her death in 1339, Joanna lived in Florence, where the Guelphs provided her with a subsidy in honor of her father's contributions to the party.[5]

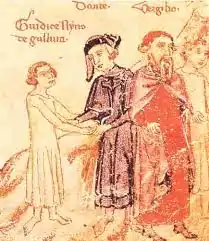

In Dante's Divine Comedy

Joanna is mentioned in Canto VIII of Dante's Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy. In the beginning of the canto, two angels with flaming swords stand on opposite sides of the valley, setting up the ritual that will take place after Dante's conversations with Nino, Joanna's father, and Conrad Malaspina. Dante and Nino share a joyous reunion, since they had known each other in life. Nino implores that Dante asks Joanna to pray for him to help him along to salvation; Joanna is the only one left who can pray for him. Nino then scorns his wife Beatrice for not mourning his death long enough, accusing her of being a fickle woman because of her remarriage to Galeazzo.

when you are far from these wide waters,

ask my Giovanna to direct her prayers for me

to where the innocent are heard.

I think her mother has not loved me

since she stopped wearing her white wimple,

which, in her coming misery, she may long for.

There is an easy lesson in her conduct:

how short a time the fire of love endures in woman

if frequent sight and touch do not rekindle it.

The viper that leads the Milanese afield

will hardly ornament her tomb as handsomely

as the cock of Gallura would have done.— Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio 8.70-81

Sordello, who had led Dante and Virgil to this valley, instructs them to look up. They watch the scene, which is so familiar to the souls on this terrace, as the snake slides sensually through the grass. Upon hearing the flapping of the angels' wings, the snake slithers away fearfully.[8]

Interpretations

Quinones argues that this canto, through the analogy of Beatrice as Eve and Joanna as Mary, exemplifies the dichotomies of sadness and hope that define the mood of Purgatorio, such as death and revival, and the fall and salvation of humankind.[9] This analogy, Quinones notes, is a misogynistic trope in which one virtuous woman redeems another sinful woman.[9] As Mary brings Jesus into the world to repent for Eve's sin of transgression, Joanna will faithfully pray for Nino to compensate for his unfaithful wife. The snake acts as the threatening of innocence, a quality which Beatrice has lost through her marriage to Galeazzo. It corresponds to the "viper" to which Nino alludes, the symbol of Galeazzo's family. Meanwhile, the act of the angels driving the snake away signifies the hope of Paradise, for the souls in Purgatory, but especially for Nino, who knows Joanna will pray for him. Quinones also notes how Nino refers to Beatrice as "her [Joanna's] mother," demonstrating his perception that Beatrice is no longer his wife and that she only exists meaningfully in relation to Joanna, his only hope of salvation.[9]

Diaz writes on Dante's portrayal of Beatrice: he has Nino identify her only by the men she has been with, thus emphasizing the perceived immorality of a woman marrying again. The viper to which Nino alludes is the symbol for the Visconti family of Milan and the cock is the symbol for Nino's own Visconti family of Pisa and Sardinia. Nino asserts that the viper will "hardly ornament [Beatrice's] tomb as handsomely as the cock," as if Beatrice were only a body to be decorated. Diaz indicates that in this scene, Beatrice's remarriage is framed as a sign of her uncontrollable lust and apathy towards Nino, even though the marriage was politically motivated and it had already been four years after Nino's death.[10]

References

- ↑ Salavert y Roca, Vicente (1956). Cerdeña y la expansión mediterránea de la Corona de Aragón, 1297-1314. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Escuela de Estudios Medievales. p. 351.

- ↑ Lansing, Richard (2010). The Dante encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 476–477. ISBN 978-0-203-83447-3. OCLC 680038637.

- ↑ Lansing, Richard (2010). The Dante encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. p. 873. ISBN 978-0-203-83447-3. OCLC 680038637.

- ↑ Toynbee, Paget (1898). A Dictionary of Proper Names and Notable Matters in the Works of Dante. unknown library. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 73.

- 1 2 3 di Renato Piattoli. "Visconti, Giovanna in "Enciclopedia Dantesca"". Treccani (in Italian). Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Salavert y Roca, Vicente (1956). Cerdeña y la expansión mediterránea de la Corona de Aragón, 1297-1314. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Escuela de Estudios Medievales. p. 354.

- 1 2 Toynbee, Paget (1898). A Dictionary of Proper Names and Notable Matters in the Works of Dante. unknown library. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 113.

- ↑ Alighieri, Dante (2004). Purgatorio. Translated by Hollander, Jean; Hollander, Robert. New York: Anchor.

- 1 2 3 Quinones, Ricardo J. (1990). "Lectura Dantis: Purgatorio VIII". Lectura Dantis (7): 47–59. ISSN 0897-5280. JSTOR 44803616 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Diaz, Sara E. Dietro a lo sposo, sí la sposa piace : marriage in Dante's 'Commedia'. ISBN 978-1-124-80769-0. OCLC 1241673090.