James W. Pumphrey (September 12, 1832 – March 16, 1906) was a livery stable owner in Washington, D.C., who played a minor role in the events surrounding the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and its aftermath. Assassin John Wilkes Booth hired a horse from Pumphrey which he used to escape after the deed.

Early life and family

James Pumphrey was born in Washington, D.C., to Levi Pumphrey and Sarah Pumphrey née Miller, and was one of six children. Upon the death of his father, being the eldest son, James inherited a livery stable at the corner of C Street and 6th Street.

James Pumphrey had two "common law" marriages and fathered seven children. He and his first wife, Margaret, had two children: Ida Elizabeth and James W., Jr. With his second wife, Mary, he fathered five children: Sarah, Mary, Josephine, Percival, and Edward.

The day of the assassination

Pumphrey was an acquaintance of conspirator John Surratt and it was Surratt who introduced Booth to him prior to the assassination. Pumphrey's stable was located near the National Hotel, which was Booth's Washington residence at the time. Booth had been hiring one particular horse, which he preferred, from Pumphrey.[1]

On April 14, 1865, after learning that Lincoln would attend that evening's performance of the play Our American Cousin, Booth went directly from Ford's Theatre to Pumphrey's livery stable to make arrangements for procuring a horse.[2] Pumphrey informed Booth that the horse he usually hired was unavailable.[3] Therefore, Booth hired a different one, a swift little bay mare with a white star on her forehead and a black tail and mane.[4] Booth told Pumphrey that he would be back to get it at around four o'clock that afternoon.

At the hour agreed upon, Booth arrived at the stable. Pumphrey warned Booth that the horse was high spirited and she would break her halter if left unattended.[5]

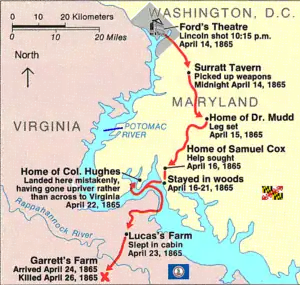

Booth mentioned to Pumphrey that he was going to Grover's Theatre, the former name of the National Theatre, as he had to write an important letter. He added that he planned afterwards to stop for a drink and then take a leisurely ride.[6] Booth did write a letter, but not at Grover's Theatre. He wrote the letter at the National Hotel; it was written to the editor of a Washington, D.C., newspaper called the National Intelligencer. In the letter, he explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating him. In addition to signing his own name, he also added those of his co-conspirators: Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Later, Booth did get a drink at Peter Taltavull's Star Saloon located next to Ford's Theatre, but he definitely did not go on a pleasure ride. Instead, Booth approached Edmund Spangler, an acquaintance and stage hand at Ford's Theatre, with the request to hold the reins of the skittish mare that he hired, while he briefly attended to some business within the theater. This business was murdering Lincoln.

After the assassination, Booth and Herold made good an escape to Virginia. Prior to crossing the Potomac River and while hiding out in some woods, Herold killed Pumphrey's horse along with his own because the horses were no longer needed.

Temporary imprisonment

In the turmoil that followed Lincoln's assassination, scores of suspected accomplices were arrested and thrown into prison by the United States Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton vigorously pursued the apprehension and prosecution of the conspirators involved in Lincoln's assassination. All the people who were discovered to have had anything to do with the assassination or anyone with the slightest contact with Booth or Herold on their flight were put behind bars. Pumphrey, having supplied the getaway horse, was jailed.[7] Ultimately, the suspects were narrowed down to a group of eight prisoners—seven men and one woman—and, along with many others, Pumphrey was released.[8]

On May 15, 1865, Pumphrey testified for the prosecution and described the horse he provided to Booth and the details of how that transaction came about.

Pumphrey's last part in the events surrounding the assassination was to wait mounted on his horse for hours outside the Old Arsenal Penitentiary. He waited in the hope of having the privilege of carrying President Andrew Johnson's reprieve to Mary Surratt. While Pumphrey regarded Mrs. Surratt as wholly innocent and exhibited the deepest sympathy for her, no reprieve was to come. On July 7, 1865, she was hanged with three of the other conspirators.

Later life and death

Pumphrey continued to operate the livery stable until some time after 1900. The demise of his stable, like many others of the day, was caused by the advent of the automobile. On 16 March 1906, Pumphrey died in Washington, D.C. He is buried in Congressional Cemetery.

Obituary

The following is Pumphrey's obituary in The Evening Star, Washington, D.C. It is from page 9 of the issue dated 16 March 1906:

James W. Pumphrey, long a prominent and active businessman of Washington, died this morning at 8:50 o'clock at his residence 477 C Street after a short illness. Mr. Pumphrey was a native of Washington, born here September 12, 1832, and lived here all his life. He was connected with the livery business for many years and an important incident in his career for which he was in no way responsible, was the circumstance that from his stables on C Street, N.W., John Wilkes Booth rented a horse prior to the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and on which he afterward escaped into Maryland where he met his death. The spurs which John Wilkes Booth wore on this expedition were borrowed from Mr. Pumphrey, although the latter had no knowledge of the purpose for which the assassin intended to employ them. For some time after this tragic event, Mr. Pumphrey was under surveillance and was not relieved until after the trial and conviction of the parties who were accused of association with John Wilkes Booth in the assassination. At the end of these trying times, Mr. Pumphrey who had already been acquitted by the courts was also acquitted in popular estimation and continued for many years in his original business. He was active, energetic and very charitable in each and every walk of life. He had during life many friends which he continued to hold until his end.

While Mr. Pumphrey was identified in a striking manner with the great closing tragedy of the Civil War, he always held, and his views were believed, that the idea of assassination arose in the mind of Booth alone, and that all of the others who were accused of participation in that sad event were influenced by that peculiar and erratic character. He exhibited the deepest sympathy for Mrs. Surratt whom he regarded as wholly innocent of participation and it is said he sat mounted on his horse for hours waiting in the hope of having the privilege of carrying President Andrew Johnson's reprieve to Mrs. Surratt then imprisoned and afterward executed at the arsenal in this city.

Mr. Pumphrey often told his friends that his only connection with the Lincoln conspiracy was that he lost his horse. Booth had taken from the Pumphrey Stables the horse which was afterward killed by Herold, Booth's companion after escaping into Maryland to avoid detection and capture. Mr. Pumphrey was for some time under arrest, in common with almost everybody that knew anything about or had any possible connection with this incident of American history but as stated he was at the time and has since been absolved of all connection with that lamentable affair.

References

- General

- Kauffman, Michael W. American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. Random House, 2004. ISBN 0-375-50785-X

- Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve, and Kunhardt Jr., Phillip B. Twenty Days. Castle Books, 1965. ISBN 1-55521-975-6

- Kunhardt Jr., Phillip B., Kunhardt III, Phillip, and Kunhardt, Peter W. Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography. Gramercy Books, New York, 1992. ISBN 0-517-20715-X

- Swanson, James: Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Harper Collins, 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-051849-3

External links

- Note from Congressional Cemetery Website - James W. Pumphrey: Owner of the livery stable where Booth rented his horse.

- Pumphrey's testimony (and that of others).