Islam is the most prominent religion on the semi-autonomous Zanzibar archipelago and could be considered the Islamic center in the United Republic of Tanzania. Around 99% of the population in the islands are Muslim, with two-thirds being Sunni Muslim and a minority Ibadi, Ismaili and Twelver Shia.[1][2] Islam has a long presence on the islands, with archeological findings dating back to the 10th century, and has been an intrinsic part in shaping mercantile and maritime Swahili culture in Zanzibar as well as along the East African coast.[3]

History of Islam in Zanzibar

Origins

Archeological findings suggest that Islam has been present in the Zanzibar archipelago for more than a millennium. Of the oldest archeological findings are large Friday mosque in Ras Mkumbuu, which has been dated back to the 10th Century,[4] and Kufic inscriptions on the mosque in Kizimkazi dated at A.D. 1106.[5] There are different historical accounts on how Islam was introduced along the East African coast, the Zanzibar archipelago included. Some suggesting that Islam was brought through Arab traders from the southern part of the Arabic peninsula, others consider the spread was initiated by groups of Zaidites from Ethiopia and Somalia, and a third group suggest that Islam came via Persia.[5] Despite these different trajectories Islam has worked as unifying force, through which a mercantile, cosmopolitan and urban Swahili culture was formed in relation to the African hinterlands.

Civilization

Historically, being Swahili along the East African coast has meant having an understanding of the message of Islam and, at least nominally, some active participation. In a context of trans-cultural interactions Islam connected people via common ethics and moral conduct and placed people along the coast within a universal imaginary of the Islamic umma.[5] Swahili townspeople were viewed to have more in common with their trade partners and fellow Muslims abroad than they had with groups in the nearby African mainland.[6] This often meant that ancestral roots were placed outside Africa, with groups stressing shirazi origin of Persia[7] and with Zanzibar becoming a central location for the Omani sultanate in the 1800s also of Arab descent.[8] Over time Islam became valued as a central aspect of what it meant to be a civilized person (in Swahili muungwana, mstaarabu), that contained assigning prestige to things connected with the distant Islamic heartlands.[9]

Islam and Culture

Islam after the revolution

Muslim Denominations

Sunni

In Zanzibar today, around 90 percent of all Muslims belong to the Sunni tradition and generally follow the Shafi’i school of jurisprudence.

Sufi Movements

Sufi brotherhoods include the Qadhriyya and Shadhiliyya. Sufi brotherhoods grew in influence during the 19th Century in relation to increased movements and flows of migrants during a time when the archipelago was a cultural, commercial and religious center along the Swahili coast. Spread through migrants from Hadramaut (Yemen) and Benadir (Somali Coast) Sufi brotherhoods were in contrast to Ibadï Islam of the ruling Omani ruling class open to former slaves and came to facilitate ways of integrating people from the African hinterlands into the Swahili society.[10]

Salafi Movements

Salafi inspired groups have been present in Zanzibar during the last part of the 20th century, and includes the Wahabi-influenced movement Ansâr Sunna (the "defenders of the Sunna").[11] The latter are characterized by engagement in da'wa (mission) in order to revive Islam while criticizing the impact on local and traditional customs (mila) on Muslim practices on the Archipelago. This includes critique of practices such as ziara (visiting tombs of shaykhs), tawasud (blessing of saints in prayers), khitma (prayer for the dead), and Maulid celebrations (the birthday of the Prophet). Salafi groups critique also include practices of traditional healing (locally referred to as uganga) and western influences, the latter especially in relation to Zanzibar's growing tourist sector which are seen related to a general moral decay in the society such as increased alcohol consumption, improper clothing and prostitution.[12]

Shia

Shia Muslims in Zanzibar include Shia Ithna’asharis, Shia Bohras and Shia Ismailis. Many within the Shia minority are of Asian descent with origins in India. For Shia Bohras, links to India remain important and are manifested in for instance marriage practices aimed at maintaining Asian identity. For Twelver Shia, Sheikh Abdulrazak Amiri, a Pan-Africanist Shia cleric based in Arusha, is working hard to spread the teachings of Ahlulbayt in Zanzibar.[13]

Muslim Institutions

The Wakf and Trust commission

The Kadhi Courts

The Mufti's Office

The Muslim Academy

Notable Muslim clerics

- Sh Abdullah Saleh Farsy was an internationally known poet, scholar and Muslim historian in Zanzibar.[14] He is well known for his contribution to Islamic knowledge, being first to translate the Quran into the Swahili language. He is the writer of the hagiography of Muslim Scholars in East Africa Baadhi ya Wanavyoni wa Kishafii wa Mashariki ya Afrika, a piece that were later translated into English.[15]

- Sh. Nassor Bachoo was a well known Muslim cleric in East Africa, particularly in Tanzania and Kenya, while he was a controversial figure in Zanzibar. He is considered to be the spiritual leader for Salafi reform movements such as the Ansâr Sunna.[11]

- The late Sh. Amir Tajir was the Chief qadi in Zanzibar.

Muslim Politics

Uamsho

Uamsho (lit. awakening) is the popularized name of Jumuiya ya Uamsho na Mihadhara ya Kiislamu Zanzibar (the Association of Islamic Awareness and Public Discourse in Zanzibar)—also known by its Swahili acronym Jumiki. Uamsho was formed in the late 1990s and registered as an NGO in 2002. The organization's aim was to promote Muslim unity and Muslim rights via public preaching.[16] Uamsho was from the start critical towards the political party of Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM), accusing the government of restricting Muslim rights and corrupting Zanzibar by its inability to uphold moral order in society. In 2012, Uamsho engaged in widespread protests for a more autonomous Zanzibar in relation to a constitutional review process in Tanzania leading to tensions with the state after holding a public march in May 2012 despite a ban on religious public meetings. With the arrest of the Uamsho leader Sh. Musa Juma, supporters took their anger to the streets leading to riots with institutions linked to CCM and Christian churches being attacked. With tensions escalating during 2012 with a new round of riots in October all of Uamsho's main leaders, such as Sh. Farid Ahmad, were eventually arrested and jailed.[17]

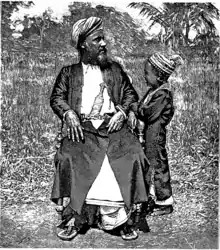

_(14578468239).jpg.webp) Ancient tomb at Tongo (1872 engraving)

Ancient tomb at Tongo (1872 engraving)

Old Mosque on the beach, 1898

Old Mosque on the beach, 1898

References

- ↑ Bakari, M.A. "Religion, Secularism, and Political Discourse in Tanzania: Competing Perspectives by Religious Organizations". Interdiciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. 8 (1): 1–34, 7. Religious demographics always state an overwhelming Muslim majority in Zanzibar even though no official census of religious belonging has been made in Zanzibar since the early 1960s.

- ↑ "Tanzania". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- ↑ Bang, Anne K. (2017-10-16). "Islam in the Swahili world". The Swahili World. Routledge. pp. 557–565. doi:10.4324/9781315691459-48. ISBN 978-1-315-69145-9.

- ↑ Pouwels, Randall L. (2000). ""The East African Coast, C. 780 to 1900 C.E.".". In Randall L. Pouwels; Nehemia Levtzion (eds.). History of Islam in Africa. Athens: Ohio University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0821412978.

- 1 2 3 Middleton, John (1992). The world of the Swahili: an African mercantile civilization. New Heaven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 161, 191. ISBN 978-0-300-06080-5.

- ↑ Topan, Farouk (2006). "From Coastal to Global: The Erosion of the Swahili "Paradox"," in The Global Worlds of the Swahili: Interfaces of Islam, Identity and Space in the 19th and 20th-Century East Africa, ed. Roman Loimeier and Rüdiger Seesemann. Berlin: Lit Verlag. pp. 56–59. ISBN 9783825897697.

- ↑ Sheriff, Abdul (2001). "Race and Class in the Politics of Zanzibar". Africa Spectrum. 36 (3): 301–318 – via https://www.jstor.org/stable/40174901.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|via= - ↑ Glassman, Jonathon (2011). War of words, war of stones racial thought and violence in colonial Zanzibar. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 25. ISBN 978-0-253-35585-0. OCLC 800854256.

- ↑ Pouwels, Randall L. (1987). Horn and Crescent. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511523885. ISBN 978-0-521-52309-7.

- ↑ Sheriff, Abdul (2001). "Race and Class in the Politics of Zanzibar". Africa Spectrum. 36:2: 301–318 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 Gilsaa, Søren (2015-07-06). "Salafism(s) in Tanzania: Theological Roots and Political Subtext of the Ansār Sunna". Islamic Africa. 6 (1–2): 30–59. doi:10.1163/21540993-00602002. ISSN 0803-0685.

- ↑ Loimeier, Roman (2011). "Zanzibar's geography of evil : the moral discourse of the Anṣār al-sunna in contemporary Zanzibar". Journal for Islamic Studies. 31:1: 4–28.

- ↑ Keshodkar, Akbar (2010). "Marriage as the Means to Preserve 'Asian-ness': The Post-Revolutionary Experience of the Asians of Zanzibar". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 45 (2): 226–240, 227. doi:10.1177/0021909609357418. S2CID 143909800.

- ↑ Loimeier, Roman. (2009). Between social skills and marketable skills : the politics of Islamic education in 20th century Zanzibar. Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2886-2. OCLC 731677136.

- ↑ Farsy, A.S. (1989). Baadhi ya Wanavyoni wa Kishafii wa Mashariki ya Afrika /The Shafi\i Ulama of East Africa, ca. 1830–1970. A hagiographical account. Translated, edited and annotated by R. L. Pouwels. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin.

- ↑ Turner, Simon (2009). "'These Young Men Show No Respect for Local Customs'—Globalisation and Islamic Revival in Zanzibar". Journal of Religion in Africa. 39 (3): 237–261, 241–242. doi:10.1163/002242009x12447135279538. ISSN 0022-4200.

- ↑ Olsson, Hans (2019-07-29). Jesus for Zanzibar: Narratives of Pentecostal (Non-)Belonging, Islam, and Nation. BRILL. pp. 44–51. doi:10.1163/9789004410367. ISBN 978-90-04-40681-0. S2CID 151571511.

External links

- "Eco-Islam hits Zanzibar fishermen BBC News, 17 February 2005

- "ROLE OF ISLAM ON POLITICS IN ZANZIBAR" by Khatib A. Rajab

.jpg.webp)