Traditional Inuit clothing is a complex system of cold-weather garments historically made from animal hide and fur, worn by Inuit, a group of culturally related indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic areas of Canada, Greenland, and the United States. The basic outfit consisted of a parka, pants, mittens, inner footwear, and outer boots. The most common sources of hide were caribou, seals, and seabirds, although other animals were used when available. The production of warm, durable clothing was an essential survival skill which was passed down from women to girls, and which could take years to master. Preparation of clothing was an intensive, weeks-long process that occurred on a yearly cycle following established hunting seasons. The creation and use of skin clothing was strongly intertwined with Inuit religious beliefs.

Despite the wide geographical distribution of Inuit across the Arctic, historically, these garments were consistent in both design and material due to the common need for protection against the extreme weather of the polar regions and the limited range of materials suitable for the purpose. Within those broad constraints, the appearance of individual garments varied according to gender roles and seasonal needs, as well as by the specific dress customs of each tribe or group. The Inuit decorated their clothing with fringes, pendants, and insets of contrasting colours, and later adopted techniques such as beadwork when trade made new materials available.

The Inuit clothing system bears strong similarities to the skin clothing systems of other circumpolar peoples such as the indigenous peoples of Alaska, Siberia and the Russian Far East. Archaeological evidence indicates that the history of the circumpolar clothing system may have begun in Siberia as early as 22,000 BCE, and in northern Canada and Greenland as early as 2500 BCE. After Europeans began to explore the North American Arctic in the late 1500s, seeking the Northwest Passage, Inuit began to adopt European clothing for convenience. Around the same time, Europeans began to conduct research on Inuit clothing, including the creation of visual depictions, academic writing, studies of effectiveness, and museum collections.

In the modern era, changes to the Inuit lifestyle led to a loss of traditional skills and a reduced demand for full outfits of skin clothing. Since the 1990s, efforts by Inuit organizations to revive historical cultural skills and combine them with modern clothing-making techniques have led to a resurgence of traditional Inuit clothing, particularly for special occasions, and the development of contemporary Inuit fashion as its own style within the larger indigenous American fashion movement.

Traditional outfit

The most basic version of the traditional Inuit outfit consisted of a hooded parka, pants, mittens, inner footwear, and outer boots, all made of animal hide and fur.[1][2] These garments were fairly lightweight despite their insulating properties: a complete outfit weighed no more than around 3–4.5 kg (6.6–9.9 lb) depending on the number of layers and the size of the wearer.[3][4] Extra layers could be added as required for the weather or activity, which generally cycled with the changing of the seasons.[5]

Although the basic outfit framework was largely the same across Inuit groups (as well as other indigenous Arctic peoples, including the Alaska Natives and those of Siberia and the Russian Far East), their wide geographic range gave rise to a broad variety of styles for basic garments, often specific to the place of origin.[2][6][7][8] The range of distinguishing features on the parka alone was significant, as described by Inuit clothing expert Betty Kobayashi Issenman in her comprehensive study on Inuit clothing Sinews of Survival: "a hood or lack thereof, and hood shape; width and configuration of shoulders; presence of flaps front and back, and their shape; in women's clothing the size and shape of the baby pouch; length and outline of the lower edge; and fringes, ruffs, and decorative inserts."[9]

Group or familial affinity was indicated by aesthetic features such as variations in the patterns made by different colours of fur, the cut of the garment, and the length of fur.[8][10][11] In some cases, the styling of a garment could indicate biographical details such as the individual's age, marital status, and specific kin group.[9][12] The vocabulary for describing individual garments in the Inuit languages is correspondingly extensive, which Issenman noted in Sinews of Survival:[1]

A few examples will indicate some of the complexities: 'Akuitoq: man's parka with a slit down the front, worn traditionally in the Keewatin and Baffin Island areas'; 'Atigainaq: teenage girl's parka from the Keewatin region'; 'Hurohirkhiut: boy's parka with slit down the front'; 'Qolitsaq: man's parka from Baffin Island' (Strickler and Alookee 1988, 175).

The concept of Inuit clothing encompasses the traditional wear of a geographically broad range of Inuit cultures from Alaska to Greenland. For the sake of consistency, this article uses Canadian Inuktitut terminology, unless otherwise noted.

| Body position | Garment name | Inuktitut syllabics[lower-alpha 1] | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torso | Qulittuq | ᖁᓕᑦᑕᖅ | Closed hooded parka, fur facing out | Men's parka, outer layer |

| Atigi | ᐊᑎᒋ | Closed hooded parka, fur facing in | Men's parka, inner layer | |

| Amauti | ᐊᒪᐅᑎ | Closed parka with pouch for infants | Women's parka | |

| Hands | Pualuuk | ᐳᐊᓘᒃ | Mitts | Unisex, double layered if necessary |

| Legs | Qarliik | ᖃᕐᓖᒃ | Trousers | Double layered for men, single for women |

| Mirquliik | ᒥᕐᖁᓖᒃ | Stockings | Unisex, double layered | |

| Feet | Kamiit | ᑲᒦᒃ | Boots | Unisex, length dependent on function |

| Tuqtuqutiq | ᑐᖅᑐᖁᑎᖅ | Overshoes | Unisex, worn when needed |

Upper body garments

Traditional Inuit culture divided labour by gender, and men and women wore garments tailored to accommodate their distinct roles. The outer layer worn by men was called the qulittaq, and the inner layer was called the atigi.[15] These garments had no front opening, and were donned by pulling them over the head.[1] Men's parkas usually had straight-cut bottom hems with slits and loose shoulders to enhance mobility when hunting.[10][16] The loose shoulders also permitted a hunter to pull their arms out of the sleeves and into the coat against the body for warmth without taking the coat off. The closely fitted hood provided protection to the head without obstructing vision. The hem of the outer coat would be left long in the back so the hunter could sit on the back flap and remain insulated from the snowy ground while watching an ice hole while seal hunting, or while waiting out an unexpected storm. A traditional parka had no pockets; articles were carried in bags or pouches. Some parkas had toggles called amakat-servik on which a pouch could be hung.[17]

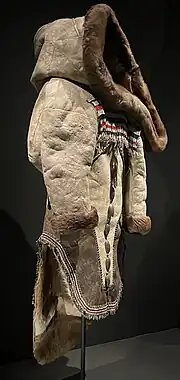

Parkas for women are called amauti and have large pouches called amaut for carrying infants.[10][18] Textile scholar Dorothy Burnham described the construction of the amaut as an "engineering feat."[19] Numerous regional variations of the amauti exist, but for the most part, the hem is left longer and cut into rounded apron-like flaps, which are called kiniq in the front and akuq in the back.[17][20] The infant rests against the mother's bare back inside the pouch, providing intimate skin to skin contact for the mother and child. A belt called a qaksun-gauti is cinched around the mother's waist on the outside of the amauti, supporting the infant without restraining it.[21][22] At rest, the infant usually sits upright with legs bent, although standing up inside the amaut is possible.[23] The roomy garment can accommodate the child being moved to the front to breastfeed or eliminate urine and faeces, and can be reversed to allow the child to sit facing the mother to play.[24][25][26] In the past, the amaut would be made smaller and narrower for widows or women past their childbearing years, who no longer needed to carry children.[27][28]

In the western Arctic, particularly among the Inuvialuit and the Copper Inuit, there is another style of women's parka called the "Mother Hubbard", adapted from the European Mother Hubbard dress.[29][30][31] The Inuit version is a full-length, long-sleeved cotton dress with a ruffled hem and a fur-trimmed hood. A layer of insulation – either wool duffel cloth or animal fur – is sewn inside for warmth, allowing it to function as winterwear.[31] Although the Mother Hubbard parka only arrived in the late 19th century, it largely eclipsed historical styles of clothing to the point where it is now seen as the traditional women's garment in those areas.[29]

The modern hooded overcoat known generically as a parka or anorak in English is descended from the Inuit garment.[32] The terms parka and anorak were adopted into English as loanwords from Aleut and Greenlandic, respectively.[33]

Trousers and leggings

Both men and women wore trousers called qarliik. During the winter, men typically wore two pairs of fur trousers to provide warmth on lengthy hunting trips.[34][35] Qarliik were waist-high and held on loosely by a drawstring. The shape and length depended on the material being used, caribou trousers having a bell shape to capture warm air rising from the boot, and seal or polar bear trousers being generally straight-legged.[36] In some regions, particularly the Western Arctic, men, women, and children sometimes wore atartaq, leggings with attached feet similar to hose, although these are no longer common.[36][37] In East Greenland, women's trousers, or qartippaat, were quite short, leaving a gap between the thigh-length boots and the bottom of the trousers.[38]

Women's qarliik were generally shaped the same as men's, but their use was adjusted for women's needs. Women wore fewer layers overall, as they usually did not go outdoors for long periods during winter.[34][35] During menstruation, women would wear a pair of old trousers supplemented inside with small pieces of hide, so as to not soil their daily outfit.[35] In some areas, women historically wore thigh-length trousers known as qarlikallaak with leggings called qukturautiik rather than full-length pants.[39] The Igluulingmiut of Foxe Basin and some of the Caribou Inuit wore a style of baggy leggings or stockings sewn to boots for long journeys. The wide leggings provided space that could be used to warm food and store small items.[40][41] These leggings were much-noted by non-Inuit who encountered them, although they ceased to be made in the 1940s due to lack of available materials.[42]

Footwear

The footwear of the traditional outfit could include up to five layers of socks, boots, and overboots, depending on the weather and terrain.[43][44] Traditionally, these garments were almost always made of caribou or sealskin, although today boots are sometimes made with heavy fabric like canvas or denim.[45][46] The traditional first layer was a set of stockings called aliqsiik, which had the fur facing inwards. The second was a pair of short socks called ilupirquk, and third was another set of stockings, called pinirait; both had outward-facing fur. The fourth layer was the boots, called kamiit or mukluks.[lower-alpha 2] The most distinguishing feature of kamiit are the soles, which are made of a single piece of skin that wraps up the side of the foot, where it is sewn to the upper. They are loose-fitting to allow for more layers, and may be secured at the top or the ankles with a drawstring or straps.[48] Kamiit could be covered with the tuqtuqutiq, a kind of short, thick-soled overshoe that provided additional insulation to the feet.[43] These overshoes could be worn indoors as slippers while the kamiit were drying out.[49] Historically, men usually rotated between multiple pairs of boots to allow them to sufficiently dry out between uses, preventing rot and extending the useful life of the boot.[48]

During the wet season of summer, waterproof boots were worn instead of insulating fur boots. These were usually made of sealskin with the fur removed. To provide grip on icy ground, boot soles could be sewn with pleats, strips of dehaired seal skin, or forward-pointing fur.[43][50][51] Boot height varied depending on the task – sealskin boots could be made thigh-high or chest-high if they were to be used for wading into water, similar to modern hip boots or waders.[45] Boots intended for use in wet conditions sometimes included drawstring closures at the top to keep water out.[52] In modern times, boot tops made of skin may be sewn to mass-produced rubber boot bottoms to create a boot that combines the warmth of skin clothing with the waterproofing and grip of artificial materials.[53]

Accessory garments

Most upper garments include a built-in hood, making separate head coverings unnecessary. The hoods of the Iñupiat people of northern Alaska are particularly notable for their distinct "sunburst" ruff around the face, made of long fur taken from wolves, dogs, or wolverines.[54] Historically, some groups like the Kalaallit of Greenland and the Alutiiq people of Kodiak Island wore separate hats instead of having hoods, in a similar fashion to the clothing worn by the Yupik peoples of Siberia.[55][56] Many modern Canadian Inuit wear a cap beneath their hood for greater insulation during winter. During summer, when the weather is warmer and mosquitoes are in season, the hood is not used; instead, the cap is draped with a scarf which covers the neck and face to provide protection from insects.[56]

Inuit mitts are called pualuuk, and are usually worn in a single layer. If necessary, two layers can be used, but this reduces dexterity. Most mitts are caribou skin, but sealskin is used for work in wet conditions, while bear is preferred for icing sled runners as it does not shed when damp. The surface of the palm can be made of skin with the fur removed to increase the grip. Sometimes a cord is attached to the mitts and worn across the shoulders, preventing them from being lost.[57] Generally, mitts are made from three pieces of skin, but traditionally some areas used only two, or even one.[58][59] To minimize the stress on the seams, the back of the mitt wraps around towards the palm, and the thumb is usually cut with the palm in one continuous piece.[60]

_and_Caribou_antler_1000-1800_CE_(bottom).jpg.webp)

Belts, which were usually simple strips of skin with the hair removed, had multiple functions. The qaksun-gauti belt secured the child in the amauti.[21] Belts tied at the waist could be used to secure parkas against the wind, and to hold small objects. In an emergency, it could be used for field repairs of broken equipment.[61] Some belts were decorated with beads or toggles carved into attractive shapes.[62]

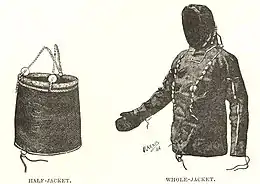

Inuit groups that regularly practiced kayaking developed specialized garments for preventing water from entering the cockpit of the kayak. In Greenlandic, these garments are called the akuilisaq (now called a spray skirt), and the watertight tuilik jacket.[63][64] The akuilisaq was a cylindrical garment that covered the wearer from the torso down, held up by suspenders that went over the shoulders. The bottom of the garment would be closed tightly over the cockpit of the kayak with a drawstring or belt.[63] The tuilik was a full-length jacket that could be drawn tight at the neck and wrists; like the akuilisaq it was tightly closed over the cockpit. Both garments prevented water from entering the cockpit, but the tuilik had the additional benefit of allowing the kayaker to roll their kayak without getting water inside their jacket.[63][64]

In the Arctic spring and summer, intense sunlight reflecting off the snowy ground can cause a painful condition known as snow blindness. In response, Inuit developed ilgaak or snow goggles, a type of eyewear which cuts down on glare but preserves the field of view.[65][66] Ilgaak are traditionally made of bone or driftwood, carved in a curve to fit the face. Narrow horizontal slits permit only a small amount of light to enter.[67]

Children's clothing

Inuit infants wore little to no clothing, as they were usually held close to their mother in the amauti.[23] What clothing they did wear, usually a small jacket, cap, mittens, or socks, was made from the thinnest skins available: fetal or newborn caribou, crow, or marmot.[68][69] The Qikirtamiut of the Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay sewed bonnets for their infants from the delicate neck and head skins of eider ducks.[70]

Children's clothing was similar in function to adult clothing, but typically made of softer materials like caribou fawn, fox skin, or rabbit. Once children were old enough to walk, they would wear a one-piece suit called an atajuq, similar in form to a modern blanket sleeper. This garment had attached feet and often mittens as well, and unlike an adult's trousers, it opened at the crotch to allow the child to relieve themselves.[69][71] Many of these suits had detached caps, which could be tied down with fringe to prevent them from getting lost.[72] The hood shape and position of decorative flourishes on these suits differentiated between genders.[69]

As children aged, they gradually transitioned into more adult-like garments. Older children wore outfits with separate parkas and trousers, although boots were generally sewn directly to the trousers.[73][74] Amautis for female children often had small amaut, and they sometimes carried younger siblings in them to assist their mother.[75][76] Clothing for girls and boys changed at puberty; in eastern Greenland, for example, both received naatsit, or under-breeches, to mark the transition.[7] In general, when girls reached puberty, amauti tails were made longer, and the hood and amaut were enlarged to indicate fertility.[27] Hairstyles for pubescent girls also changed to indicate their new status.[7][77]

Modern usage

Many Inuit wear a combination of traditional skin garments, garments which use traditional patterns with imported materials, and mass-produced imported clothing, depending on the season and weather, availability, and the desire to be stylish.[78] The fabric-based atikłuk and the Mother Hubbard parka remain popular and fashionable in Alaska and Northern Canada, respectively.[79] Mothers from all occupations still make use of the amauti, which may be worn over fabric leggings or jeans.[26][80] Both handmade and imported garments may feature logos and images from traditional or contemporary Inuit culture, such as Inuit organizations, sports teams, musical groups, or common northern foodstuffs.[81][82][83] Although it is uncommon for modern Inuit to wear complete outfits of traditional skin clothing, fur boots, coats and mittens are still popular in many Arctic places. Skin clothing is preferred for winter wear, especially for Inuit who make their living outdoors in traditional occupations such as hunting and trapping, or modern work like scientific research.[84][85][86][87] Traditional skin clothing is also preferred for special occasions like drum dances, weddings, and holiday festivities.[87][88]

Materials

Because the Arctic climate is not suitable for cultivating the plants and animals that produce most textiles, Inuit made use of fur and skins from local animals.[89] The most common sources of hide for Inuit clothing are caribou and seals, caribou being preferred for general use.[15][90][91] Historically, seabirds were also an important source for clothing material, but use of seabird skins is now rare even in places where traditional clothing is still common.[92] Less commonly used sources included bears, dogs, foxes, ground squirrels, marmots, moose, muskoxen, muskrats, whales, wolverines, and wolves. The use of these animals depended on location and season. When compared to caribou and seal, other skins often had major drawbacks such as fragility, weight, or hair loss, which precluded their more common use.[93][94][95] Traditionally, all clothing material was obtained from hunting and hand-prepared, but today, many seamstresses also make use of materials purchased from northern supply stores, including commercially prepared skins of traditionally used animals, non-traditional skins like cowhide or sheepskin, and even imitation fur.[96][97]

Regardless of the source animal, Inuit traditionally used as much of the carcass as possible. Every portion of the hide had a specific use depending on its characteristics.[98] Tendons and other membranes were used to make tough, durable fibres, called sinew thread or ivalu, for sewing clothing together. Feathers were used for decoration. Rigid parts like bones, beaks, teeth, claws, and antlers were carved into tools or decorative items.[93] The soft material shed from antlers, known as velvet, was used for tying back hair.[93] Intestine from seals and walruses was used to make waterproof jackets for inclement weather.[20] The Russian word kamleika is sometimes used to describe all garments made from gut, although it originally only referred to gut robes made by the Aleut people of the Aleutian Islands.[55][99][100]

Due to the value of skins, old or worn-out skin clothing was historically not discarded at the end of the season. Instead, it was repurposed as bedding or work clothing, or taken apart and used to repair newer garments.[98] In times of extreme need, such as when the caribou hunt failed, scraps of old garments could be re-sewn together into whole new garments, although these were less durable and provided less insulation.[101][102]

Through socialization and trade, Inuit groups throughout their history disseminated clothing designs, materials, and styles between themselves. There is evidence indicating that prehistoric and historic Inuit gathered in large trade fairs to exchange materials and finished goods; the trade network that supported these fairs extended across some 3,000 km (1,900 mi) of Arctic territory.[103] They also encountered and incorporated concepts and materials from other indigenous Arctic peoples such as the Chukchi, Koryak, and Yupik peoples of Siberia and the Russian Far East, the Sámi people of Scandinavia, as well as non-Inuit North American indigenous groups.[104][105][106]

Caribou and seal

_hispida_(Ringed_seal)_fur_skin.jpg.webp)

The hide of the barren-ground caribou, an Arctic subspecies of caribou, was the most important source of material for clothing of all kinds, as it was readily available, versatile, and, when left with the fur intact, very warm.[107] Caribou fur grows in two layers, which trap air, which is then warmed up by body heat. The skin itself is thin and supple, making it light and flexible.[93] Caribou had to be hunted at specific times to ensure maximum quality of the skins. If taken too early in the spring, the hide would have holes from warble flies and hair loss from seasonal moulting. Animals taken too late in the fall have skin too thick and heavy for clothing.[108] Each piece of the hide had qualities that made it suitable for particular uses: for example, the tough leg skins were used for items that required durability, while the thick skin from the caribou's back was used for the large front piece of parkas.[18][109] Depending on availability, hides from thicker-skinned male caribou were preferred for men's clothing, which needed to be tougher for hunting, and thinner skin from female caribou was used for women's garments.[110] Caribou sheds badly when exposed to moisture, so it is not suitable for wet-weather garments.[111] Caribou hide could also be shaved and used for footwear and decorative fringe.[112]

The hide of Arctic-dwelling seals is both lightweight and water-repellent, making it ideal as single-layer clothing for the wet weather of summer. Year-round, it was used to make clothing for water-based activities like kayaking and fishing, as well as for boots and mittens.[20] Seal hide is porous enough to allow sweat to evaporate, making it ideal for use as boots. Of the four Arctic seals, the ringed seal and the bearded seal are the most commonly used for skin clothing, as they have a large population and are widely distributed. Harbour seals have a wide distribution but lower population, so they are less commonly used. Clothing made from harp seals has been reported, but documentation is lacking.[113] The skin of younger seals killed in autumn is traditionally preferred for aesthetic reasons, as it is darker and less likely to be damaged.[91]

Bird skins

The use of bird skins has been documented across all Inuit groups, although it was most common in the eastern and western Arctic, where larger animals like caribou were less available, compared to the central Arctic.[114][115][116] Bird skin, feet, and bones were used to make clothing of all kinds, as well as tools, containers, and decorations.[114] Compared to caribou skin, bird skins have several disadvantages that make it impractical to rely on them for general use except where better materials are unavailable. Feathers make these skins bulky, and they are less durable overall. Their small size means that more animals are required to make a larger garment. Finally, their skins are less consistent than caribou or seal, so using them efficiently requires more technical knowledge on the part of the seamstress.[117] More than two dozen species of birds have been identified in Inuit clothing, including species of auk, cormorant, crow, eider duck, goose, guillemot, loon, ptarmigan, puffin, seagull, and swan.[114][118][119] The toughest and most desirable skins came from diving birds.[120]

The Qikirtamiut of the Belcher Islands relied on eider duck as their primary clothing material, as there were no caribou on the islands.[121] As a result, they developed an extensive knowledge of the technical properties of eider duck skins depending on the age, gender, and season of each bird.[122] Skins were used according to the properties desired for the garment being made – the tougher skins of adult male ducks were used for hunter's garments, which required durability, while the more flexible skins of juvenile ducks were selected for children's clothing.[123] The unique characteristics of the types of feathers on the body were also taken into account. The more flexible back skin of the duck would be used for parts that required flexibility, like the hood, while the more thickly feathered skin from the belly would be used for the parka body, where warmth was required.[124]

Other natural materials

Polar bear was a major source of winter garments for Greenlandic Inuit in the 19th century.[4][7] Like caribou fur, polar bear fur grows in dual layers, and is prized for its heat-trapping and water-resistant properties. The long guard hairs of dogs, wolves, and wolverines were preferred as trim for hoods and mittens.[125] The fur of arctic foxes was sometimes also used for trim, and was suitable for hunting caps and the insides of socks. In some areas, women's clothing was made of fox hides, and it was used to keep the breasts warm during breastfeeding. Adult musk-ox hide is too heavy to be used for most clothing, but it was used for mittens as well as summer caps, as the long hairs kept mosquitoes away. It was also suitable as bedding.[111][126] In places where larger animals were scarce, such as Alaska and Greenland, the skins of small animals like marmots and Arctic ground squirrels were sewn together to make parkas. These animals were also used to make decorative pieces.[70][111]

The skin of cetaceans like beluga whales and narwhals was sometimes used for boot soles.[112] Whale sinew, especially from the narwhal, was prized as thread for its length and strength. Tusks from narwhal and walrus provided ivory, which was used for sewing tools, clothing fasteners, and ornaments. In Alaska, fish skins were sometimes used for clothing and bags, but this is not well-documented in Canada.[114][120]

Dried grass and moss were used as insulation and absorbent material. They could be placed inside the stocking to absorb perspiration from the feet, or at the bottom of the amaut to serve a similar function to a diaper for an infant.[127] Some groups also stuffed their needle cases with moss to form a sort of pincushion.[128]

Fabric and artificial materials

.jpg.webp)

Beginning in the late 1500s, contact with non-Inuit, including American, European, and Russian traders and explorers, began to have an increasingly large influence on the construction and appearance of Inuit clothing.[9] These people brought trade goods such as metal tools, beads, and fabric, which began to be integrated into traditional clothing.[129][130] For example, imported duffel cloth was useful for boot and mitt liners, and quilted fabric was used to line parkas.[131][132] Sewing machines appeared as trade goods beginning in the 1850s, allowing for easy production of garments made from imported cloth.[132][133]

Where men often adopted ready-made European garments, Inuit women after European contact used purchased or traded cloth to create garments that suited their needs.[134] Beginning in the middle of the 19th century, the Alaskan Iñupiat began to use colourful imported fabrics like drill and calico to make over-parkas to protect their caribou garments from dirt and snow.[31] Men's were shorter while women's were longer with ruffled hems; the Iñupiat called both styles atikłuk. The longer women's version eventually made its way eastward to the Mackenzie Delta area of the Northwest Territories, where it became known as the Mother Hubbard parka (from the European Mother Hubbard dress) or cloth parka.[31][132] The Mother Hubbard parka was originally worn with the fur amauti (overtop or underneath), but later styles were insulated with duffel cloth or fur and could be worn on their own, especially during summer. These garments were valued by women as they were simple to make compared to the intensive process of making skin clothing. Their exotic materials were considered a sign of wealth and status.[31][135]

While they became common, these new materials, tools, and techniques generally did not alter the basic design of the traditional skin clothing system, which has always remained consistent in form and function. In many cases Inuit were dismissive of so-called "white men's clothing"; the Inuvialuit referred to cloth pants as kam'-mik-hluk, meaning "makeshift pants".[136] The Inuit selectively adopted foreign elements that simplified the construction process (such as metal needles) or aesthetically modified the appearance of garments (such as seed beads and dyed cloth), while rejecting elements that were unsuitable (such as metal fasteners, which may freeze and snag, and synthetic fabrics, which absorb perspiration).[55][137]

Construction and maintenance

.jpg.webp)

Historically, women were responsible for managing every stage of the clothing production process, from preparation of skins to the final sewing of garments. The skills relating to this work were traditionally passed down in families from grandmothers and mothers to their daughters and grandchildren.[10][138] Women learned not only sewing skills, but information about game animals, the local environment, and the seasons.[139] An extensive vocabulary existed to describe the specifics of skin preparation and sewing.[139]

Although the learning process began in early childhood, fully mastering these skills could take until a woman was into her mid-thirties.[10][138] Learning to make traditional clothing has always been a process of acquiring tacit knowledge by observing and learning the sewing process, then creating items independently without explicit verbal directions in what can be characterized as learning-by-doing.[140] Traditionally, young girls practiced by creating dolls and doll clothes from scraps of hide before moving on to small clothing items like mittens intended for actual use.[141]

To ensure the survival of the family unit and the community as a whole, garments had to be sewn well and properly maintained. Heat loss from poorly constructed clothing reduced the wearer's ability to perform essential tasks in camp and on the hunt and limited their ability to travel.[142] It could also lead to negative health outcomes including illness, hypothermia, or frostbite, which in extreme cases can result in loss of limbs and eventually death.[90][142][143] For this reason, most garments, especially boots, were constructed from as few pieces as possible to minimize the number of seams, which in turn minimized heat loss.[101][102]

Preparation of new items occurred on a yearly cycle that typically began after the traditional hunting seasons. Caribou were hunted in the late summer and autumn from approximately August to October, and sea mammals like seals were hunted from December to May.[144] Production of clothing was an intensive process undertaken by the entire community gathered together in a camp. Men contributed by butchering the animals and stockpiling food, while women processed hides and sewed the garments. The sewing period that followed hunting could last for two to four weeks.[145][146] It could take up to 300 hours just to prepare the approximately twenty caribou hides necessary for a five-member family to each have two sets of everyday clothing, and another 225 hours to cut and sew the garments from them.[147][148][149] There is no clear estimate for the comparable number of seal hides required to fully clothe a five-member family, although it required approximately eight seal skins to create two parkas and two pairs of pants for one man, and six skins to create boots and mitts for a family of that size.[150]

Tools

Inuit seamstresses traditionally used tools handcrafted from animal materials like bone, baleen, antler and ivory, including the ulu (Inuktitut: ᐅᓗ, plural: uluit, 'woman's knife'), knife sharpener, blunt and sharp scrapers, needle, awl, thimble and thimble-guard, and a needlecase.[20][107][151][152] Uluit were particularly important tools for seamstresses. Considered to be integral to their identity, they were often buried with their owner.[152][153] As well as animal materials, wood and stone were also often used to make uluit. When available, meteoric iron or copper was cold worked into blades by a process of hammering, folding, and filing.[145][154]

After contact with non-Inuit explorers and traders, Inuit began to make use of sheet tin, brass, non-meteoric iron, and steel, obtained by trading or scrapping.[145][155] They also adopted steel sewing needles, which were more durable than bone needles.[156] European contact also brought scissors to the Inuit, but they were not widely adopted, as they do not cut furry hides as cleanly as sharp knives.[157] Today, many tools are mail-ordered or handmade to suit from available materials.[155] During fieldwork conducted on Baffin Island in the 1980s, anthropologist Jill Oakes described uluit being made from saw blades, with handles made from materials as varied as "plastic bread board, an old gun stock or scrap lumber," shaped to fit the user's hand.[158]

Hide processing

.jpg.webp)

The first stage was the harvesting of the skin from the animal carcass after a successful hunt. Generally, the hunter would cut the skin in such a way that it could be removed in one piece. Skinning and butchering an adult caribou could take an experienced hunter up to an hour.[159] While butchering of caribou was handled by men, butchering of seals was mostly handled by women.[153][160]

After the skin was removed, the hides would be dried on wooden frames, then laid on the knees or on a scraping platform and scraped of fat and other tissues with an ulu until soft and pliable.[107][161][162] Most skins, including bird skins, were processed in roughly the same way, although processing oily skins like seal and polar bear sometimes required the additional step of degreasing the hide by dragging it across gravel or, today, washing it with soap.[163][164] If the hide was soiled with blood, rubbing with snow or soaking in cold water could remove the stain.[165] Sometimes the fur would need to be removed so the hide could be used for things like boot soles. This was usually done with an ulu, or if the hair had been loosened by putrefaction or soaking in water, a blunt scraping tool could also suffice.[161] The hide would be repeatedly scraped, stretched, chewed, rubbed, wrung or folded up, soaked in liquid, and even stamped on to soften it further for sewing.[166][167] The softening process was continued until the women judged the skin was ready – up to twelve distinct stages might be required.[151] Badly processed hides would stiffen or rot, so correct preparation of hides was essential to ensure the quality of the clothing.[147]

Sewing of garments

When the hide was ready, the process of creating each piece could begin. The first step was measuring, a detailed process given that each garment was tailored for the wearer. No standardized sewing pattern was used, although older garments were sometimes used as models for new ones.[10][168] Traditionally, measurement was done by eye and by hand alone, although some seamstresses now make bespoke paper patterns following a hand and eye measurement process.[23][46][49] The skins were then marked for cutting, traditionally by biting or pinching, or with an edged tool, although in modern times ink pens may be used.[169] The direction of the fur flow is taken into account when marking the outline of the pieces.[170] Most garments were sewn with fur flowing from top to bottom, but strips used for trim had a horizontal flow for added strength.[171] Once marked, the pieces of each garment would be cut out using the ulu, taking care not to stretch the skin or damage the fur. Adjustments were made to the pattern during the cutting process as need dictated. The marking and cutting process for a single amauti could take an experienced seamstress an entire hour.[172] Up to forty pieces might be cut out for the most complex garments like the outer parka, although most used closer to ten.[173]

Once the seamstress was satisfied that each piece was the appropriate size and shape, the pieces were sewn together to make the complete garment. A good fit was essential for comfort.[174] Traditionally, Inuit seamstresses used thread made from sinew, called ivalu. Modern seamstresses generally use thread made from cotton, linen, or synthetic fibres, which are easier to find and less difficult to work with, although these materials are less waterproof compared to ivalu.[175][176]

Tight, high-quality seams were essential to prevent cold air and moisture from entering the garment.[143] Four main stitches were used: from most to least common, they were the overcast stitch, the tuck or gathering stitch, the running stitch, and the waterproof stitch or ilujjiniq.[172][177] The overcast stitch was used for the seams of most items. The tuck or gathering stitch was used to join pieces of uneven size. The running stitch was used to attach facings or insert material of a contrasting colour. The waterproof stitch is a uniquely Inuit development, which Issenman described as being "unequalled in the annals of needlework."[172][178] The stitch was mostly employed on boots and mitts. Two lines of stitching made up one waterproof seam. On the first line, the needle pierced partway through the first skin, but entirely through the second; this process was reversed on the second line, creating a seam in which the needle and thread never fully punctured both skins at the same time. Ivalu swells with moisture, filling the needle holes and making the seam waterproof.[64][179]

Maintenance

Once created, Inuit skin clothing must be properly maintained, or it will become brittle, lose hair, or rot. Warmth and moisture are the biggest risks to clothing, as they promote the growth of decay-inducing bacteria. If the garment is soiled with grease or blood, the stain must be rubbed with snow and beaten out quickly.[180] Beyond practical considerations, wearing clean clothing on a hunt was considered an important sign of respect for the spirits of the animals.[181]

Historically, Inuit used two main tools to keep their garments dry and cold. The first was the tiluqtut, or snow beater, a rigid implement made of bone, ivory, or wood. It was used to beat the snow and ice from clothing before entering the home.[182] The second was the innitait, or drying rack.[183] Once inside the home, garments were laid over the rack near a heat source so they could be dried slowly. All clothing, especially footwear, was checked daily for damage and repaired immediately if any was discovered. Boots were chewed, stretched, or rubbed across a boot softener to maintain durability and comfort.[180][184] Although women were primarily responsible for sewing new garments, both men and women were taught to repair clothing and carried sewing kits while travelling for emergency repairs.[180]

Major principles

Inuit clothing expert Betty Kobayashi Issenman identifies five aspects common to the clothing worn by all circumpolar peoples, made necessary by the challenges particular to survival in the polar environment: insulation, control of perspiration, waterproofing, functionality, and durability.[6] Other researchers of Arctic clothing have independently described similar governing principles, generally centred around warmth, humidity control, and sturdiness.[116][185] Archaeologist Douglas Stenton noted that cold-weather garments such as Inuit clothing must maintain two attributes to be useful: "(i) protection of the body and (ii) the maintenance of task efficiency."[186] Interviews with Qikirtamiut seamstresses in the late 1980s found they sought similar attributes when deciding which bird skins to use and where.[122]

- Insulation and heat conservation: Clothing worn in the Arctic must be warm, especially during the winter, when the polar night phenomenon means the sun never rises and temperatures can drop below −40 °C (−40 °F) for weeks or months.[6] Inuit garments were designed to provide thermal insulation for the wearer in several ways. Caribou fur is an excellent insulating material: the hollow structure of caribou hairs helps trap warmth within individual hairs, and the air trapped between hairs also retains heat.[18] Each garment was individually tailored to the wearer's body with complex techniques including darts, gussets, gathers, and pleats.[187] Garments were generally bell shaped to retain warm air.[188] Openings were minimized to prevent unwanted heat loss, but in the event of overheating, the hood could be loosed to allow heat to escape.[189] In many places, long, resilient hairs from wolves, dogs, or wolverines was used for hood trim, which reduced wind velocity on the face.[189][190] Layers were structured so that garments overlapped to reduce drafts.[191][192] For the warmer weather of spring and summer, where average temperatures can range from −0.8 °C (30.6 °F) to 11.4 °C (52.5 °F) in Nunavut, only a single layer of clothing was necessary.[193][194] Both men and women wore two upper-body layers during the harsher temperatures of winter. The inner layer had fur on the inside against the skin for warmth, and the outer layer had fur facing outward.[10][20][195]

- Humidity control: Perspiration eventually leads to the accumulation of moisture in closed garments, which must be managed for the comfort and safety of the wearer.[12][196] The carefully tailored layers of traditional clothing allowed fresh air to circulate through the outfit during physical exertion, removing air that was saturated with perspiration and keeping both the garments and the body dry.[98] As well, animal skin is relatively porous and allows some moisture to evaporate.[45] When temperatures are low enough for moisture in the air to freeze, it accumulates on the surface of fur as frost crystals that can be brushed or beaten away. Fur ruffs on hoods collect moisture from breath; when it freezes it can be brushed away with one hand.[189] For footwear, animal skin provides greater condensation control than nonporous materials like rubber or plastic, as it allows moisture to escape, keeping the feet drier and warmer for longer.[45] In comparison to skin and fur, woven fibres like wool absorb moisture and hold it against the body; in freezing temperatures, this causes discomfort, limited movement, and eventually, life-threatening heat loss.[12][23][196]

- Waterproofing: Making garments waterproof was a major concern for Inuit, especially during the wetter weather of summer. The skin of marine mammals like seals sheds water naturally, but is lightweight and breathable, making it extremely useful for this kind of clothing. Before artificial waterproof materials became available, seal or walrus intestine was commonly used to make raincoats and other wet-weather gear. Skilful sewing using sinews allowed the creation of waterproof seams, particularly useful for footwear.[197]

- Functional form: Garments were tailored to be practical and to allow the wearer to perform their work efficiently. As the Inuit traditionally divided labour by gender, clothes were tailored in distinct styles for men and women. A man's coat meant to be worn while hunting, for example, would have shoulders tailored with extra room to provide unrestricted movement, while also allowing the wearer to pull their arms into the garment and close to the body for warmth.[192] The long back flap kept the hunter's back covered when crouched over and waiting for an animal.[198] The amauti was tailored to include a large back pouch for carrying infants.[10] For both men and women's clothing, gores and slits allowed for parkas to be donned rapidly, and hoods were constructed to provide warmth while minimizing loss of peripheral vision.[98]

- Durability: Inuit clothing needed to be extremely durable. Since the creation of skin clothing was a labour-intensive, highly customized process, with base materials available only seasonally depending on the source animal, badly damaged garments were not easy to replace.[107][199] To increase durability, seams were placed to minimize stress to the skins.[191][192] For example, in the parka, the shoulder seam is dropped off the shoulder. On the trousers, seams are placed off the side of the legs.[180] Different cuts of skin were used according to their individual qualities – hardier skin from the animal's legs was used for mitts and boots, which required toughness, while more elastic skin from the animal's shoulder would be used for a jacket's shoulder, which required flexibility.[98] The use of fasteners and closures was minimized to reduce the need for maintenance.[192] Rips or tears would compromise the garment's ability to retain heat and regulate humidity, so they were repaired as soon as possible, including in the field if necessary.[180][192]

Decorative techniques

Historically, Inuit have added visual appeal to their clothing with ornamental trim and inlay, dye and other colouring methods, decorative attachments like pendants and beads, and design motifs, integrating and adapting new techniques and materials as they were introduced by cultural contact.[200][201] The variety of techniques developed by Inuit allowed for a great deal of customization and self-expression in the appearance of garments.[8] Decorative elements had cultural and spiritual connotations, and may have had practical benefits. They may have served as identifiers: for the seamstress who made them, or to allow people to identify one another at a distance in harsh weather.[202]

Archaeological and artistic evidence since the 15th century documents the evolution of the visual style of garments. Contact with new cultures, as well as the arrival of new materials like cloth and beads hastened the evolution of fashion among Inuit and made the changes in style more evident to outsiders.[203][204][205] For example, in the 1920s, whaling ships brought distinct styles of amauti from the Uqqurmiut Inuit of south Baffin Island to the Tununirmiut Inuit in the northern part of the island.[204]

Traditionally, trim and inlays were made of fur and skin. Variations in the fur direction, length, texture, and colour created visual contrast with the main garment. In general, women's parkas had much more decoration than men's, although men's parkas sometimes had specific markings on the shoulders to visually emphasise the strength of their arms.[206][18][75] Historically, markings on the forearms of amauti served as a visual reminder of women's dexterity and sewing skills.[206][23] Inuit groups along the west coast of Hudson Bay, as well as the central Arctic Copper Inuit, used narrow inlays of white fur in a way that mimicked women's traditional tattoo designs.[207][208] Dehaired skin was sometimes used decoratively, as in the Labrador Inuit use of scalloped trim on boots.[209] Textile materials such as braided cord, rickrack, and bias tape were adopted as they became available.[210][211]

Starting in the 1890s, the Alaskan Iñupiat began to make use of elaborate decorative trim on almost all their garments, often in bands of geometric patterns which they called qupak.[212] When traders brought rolls of colourful fabric trim, the Iñupiat incorporated pieces of it into qupak. When the style spread east into Canada, it acquired the name "delta trim", possibly in reference to the Mackenzie Delta.[213][214][215] The Kalaallit of Greenland are particularly known for a decorative trim known as avittat, or skin embroidery, in which tiny pieces of dyed skin are appliquéd into a mosaic so delicate it resembles embroidery.[216] While somewhat visually similar, it is unclear if qupak and avittat are related techniques.[217] Another Kalaallit technique, slit weaving, involves a strip of hide being woven through a series of slits in a larger piece of a contrasting colour, producing a checkered pattern.[216]

Some skins were coloured or bleached. Dye was used to colour both skins and fur. Shades of red, black, brown, and yellow were made from minerals such as ochre and galena, obtained from crushed rocks and mixed with seal oil.[161][219] Plant-based dyes were available in some areas as well. Alder bark provided a red-brown shade, and spruce produced red.[161] The dying process also made the boots more water-repellent.[220] Lichen, moss, berries, and pond algae were also used.[216] Skins could also be tanned with smoke to make them brown, or left outside in the sun to bleach them white.[112][221] In modern times, some Inuit use commercial fabric dye or acrylic paint to colour their garments.[161][222][223]

Many Inuit groups used attachments like fringes, pendants, and beads to decorate their garments. Fringing on caribou garments was practical as well as decorative, as it could be interlocked between layers to prevent wind from entering, and would weigh down the edges of garments to prevent them from curling up.[224] The paw skins from animals like wolves and wolverines were sometimes hung decoratively from men's belts.[225] Pendants were made from all kinds of materials. Traditionally soapstone, animal bone, and teeth were the most prevalent, but after European contact, items like coins, bullet casings, and even spoons were used as decorations.[226][227][228]

Inuit clothing makes heavy use of motifs, which are figures or patterns incorporated into the overall design of the garment. In traditional skin clothing, these are added with contrasting inserts, beadwork, embroidery, appliqué, or dyeing. The roots of these designs can be traced back to the Paleolithic era through artifacts which use basic forms like triangles and circled dots.[229] Later forms were more complex and highly varied, including scrolls and curlicues, heart shapes, and plant motifs.[230][231] It has been suggested that these more complex motifs may have come from contact with First Nations peoples.[232] There are even examples of beadwork on parkas from the early 20th century that represent complex images like faces and sailing ships.[233]

Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, the designs on fur inserts used for kamiit became increasingly elaborate, and by the 1980s were incorporating designs drawn from modern culture. Jill Oakes and Rick Riewe describe the increased variety: "a larger number of intricate insets were used, including animals, flowers, logos, letters, hockey team names, people's names, community names, snowmobile brand names, and political concerns."[234] Women's designs have traditionally been placed horizontally as a band around the top of the shaft, while motifs on men's kamiit have traditionally been placed vertically down the shaft of the boot.[235]

Beadwork

Beadwork was generally reserved for women's clothing. Before European contact, beads were made from amber, stone, tooth, and ivory. Beginning in the 1700s, European traders introduced trade beads: colourful, highly prized glass beads that could be used as decoration or to trade for other valuables. The Inuit referred to these beads as sapangaq ("precious stone").[236][237] The Hudson's Bay Company was the largest purveyor of beads to the Inuit, trading strings of small seed beads in large batches, as well as more valuable beads such as the Venetian-made Cornaline d'Aleppo, which were red with a white core.[238]

Access to trade beads increased significantly in the 1860s, and by the early 20th century, many Inuit groups had developed distinct and elaborate styles of beadwork.[239][240] Sections of strung seed beads were used as fringe or stitched directly onto the hide. Some beadwork was applied to panels of skin, which could be removed from an old garment and sewn onto a new one; such panels were sometimes passed down through families.[238][241] Driscoll-Engelstad describes a style typical of the eastern Arctic, where long strings of beads in horizontal bars were draped across the chest. In the central Arctic, beads were set on parkas in the areas where fur insets and skin fringes had traditionally been placed; some of these patterns echoed traditional tattoo designs.[240][242] Elaborately beaded and embroidered amauti can take weeks or months to make.[87] Because of the intense work required, few seamstresses today create elaborate beaded panels by hand. Some purchase premade beaded pieces from fabric stores.[210][243]

Spirituality and identity

The entire process of creating and wearing traditional clothing was intimately connected with Inuit spiritual beliefs. Hunting was seen as a sacred act with ramifications in both the material and spiritual worlds.[244][245] It was important for people to show respect and gratitude to the animals they killed, to ensure that they would return for the next hunting season. Specific practices varied depending on the animal being hunted and the particular Inuit group. Wearing clean, well-made clothing while hunting was important, because it was considered a sign of respect for the spirits of the animals. Some groups left small offerings at the site of the kill, while others thanked the animal's spirit directly. Generous sharing of the meat from a hunt pleased the animal's spirit and showed gratitude for its generosity.[244][246]

Specific rituals existed to placate the spirits of polar bears, which were seen as particularly powerful animals. It was believed that the spirits of polar bears remained within the skin after death for several days. When these skins were hung up to dry, desirable tools were hung around them. When the bear's spirit departed, it took the spirits of the tools with it and used them in the afterlife.[181]

For many Inuit groups, the timing of sewing was governed by spiritual considerations. Traditionally, women never began the sewing process until hunting was completely finished, to allow the entire community to focus exclusively on the hunt.[247] The goddess Sedna, mistress of the ocean and the animals within, disliked caribou, so it was taboo to sew sealskin clothing at the same time as caribou clothing. Production of sealskin clothing had to be completed in the spring before the caribou hunt, and caribou clothing had to be completed in fall before the time for hunting seal and walrus.[132][248] Individual groups had local taboos that also played a part in the timing of the sewing process.[249]

Many groups also had clothing taboos related to death. An infant whose older siblings had died might be dressed in garments made from a mix of caribou and sealskin, or with contrasting fur flow, to hide the child from evil spirits.[250] Relatives of a deceased person might be prohibited from working on clothing for a certain period of time after a death.[251] Deceased adults were laid out in their clothes and then wrapped in skins. Their remaining clothing was discarded or left at the grave site, and their tools – sewing tools for women and hunting tools for men – were left with them as well. People who touched a dead body might have to ritually cleanse or discard their own garments.[252]

Wearing skin clothing traditionally created a spiritual connection between the wearer and the animals whose skins are used to make the garments. This pleased the animal's spirit, and in a show of gratitude, it would return to be hunted in the next season. Skin clothing was also thought to impart the wearer with the animal's characteristics, like endurance, speed, and protection from cold. Shaping the garment to resemble the animal enhanced this connection. For example, the animal's ears were often left on parka hoods to imbue the hunter with acute hearing, and contrasting patterns of light and dark fur were placed to emulate the animal's natural markings.[207][253][254] In particular, the use of the caribou's white underbelly fur, called the pukiq, had strong spiritual connotations, referencing the life-giving power of both women and the caribou.[207] Some researchers have theorized that these light and dark patterns, later often rendered with beadwork rather than fur, may represent the animal's bones.[253][255] The Copper Inuit used a design mimicking a wolf's tail on the back of their parkas, referencing the natural predator of the caribou.[256] Hoods on Iñupiat garments almost always had what anthropologist Cyd Martin describes as "hood roots, triangular gussets of a contrasting colour set into the front of the garments...resembl[ing] walrus tusks."[130]

Amulets made of skin and animal parts were worn for protection and luck, and to invest the wearer with the powers of the associated animal or spirit.[7][130][257] Children were considered to be vulnerable and in need of the most protection, so their clothing was hung with large numbers of protective amulets.[258] Both the material of the amulet and its position on the body had spiritual importance.[253][258] Hunters might wear a pair of tiny model boots while out hunting to ensure that their own boots would last. Weasel skins sewn to the back of the parka provided speed and cleverness.[259] For women, ermine skins provided liveliness and energy, while loon skins helped with music and dancing.[260] The rattling of ornaments like bird beaks was thought to drive off evil spirits.[261] The bodies of small insects like bees might be kept in small pouches sewn close to the skin. Even clothing could become an amulet of sorts: to prevent illness, the Paatlirmiut group of Caribou Inuit wore pieces of clothing taken from people who had recovered from illness.[262]

Ceremonial clothing

In addition to their everyday clothing, many Inuit had a set of ceremonial clothing made of short-haired summer skins, worn for dancing or other ceremonial occasions. In particular, the intricately striped and fringed dance clothing of the Copper Inuit has been extensively studied and preserved in museums worldwide.[263][264] Dance parkas were generally not hooded; instead, special dancing caps were worn.[265][266] These caps were sewn with the beaks of birds like loons and thick-billed murres, invoking the vision and speed of the animals, and white stoat skins to invoke the animal's cunning and ability to camouflage itself in snow.[267][268] Dance clothing was strongly related to shamanistic clothing, indicated by designs that reference the spiritual world.[269] Gutskin clothing could also be donned for ceremonial purposes.[270]

Inuit shamans, called angakkuq,[lower-alpha 3] usually wore garments like those of laypeople, but which included unique accessories or design elements to differentiate their spiritual status. The intricately designed parka of the angakkuq Qingailisaq, inspired by spiritual visions, is an example of such a garment. It was acquired for the American Museum of Natural History in 1902 and has been studied extensively by scholars of Inuit culture.[272]

Shamans from groups which permitted the hunting of albino caribou, such as the Copper and Caribou Inuit, might have parkas whose colouration was inverted compared to regular garments: white for the base garment and brown for the decorative markings.[273] The fur used for a shaman's belt was white, and the belts themselves were adorned with amulets, coloured cloth, and tools, often representative of important events in the shaman's life or given to the shaman by supplicants seeking magical assistance.[274][275][276] Mittens and gloves, though not always visually distinct, were important components of shamanic rituals; they were considered to protect the hands and serve as a symbolic reminder of the shaman's humanity.[277][278] The use of stoat skins for a shaman's clothing invoked the animal's intellect and cunning, while foot-bones taken from foxes or wolves invoked running speed and endurance.[106][269]

Traditional ceremonial and shamanic clothing also incorporated masks made of wood and skin to invoke supernatural abilities, although this practice largely died out after the arrival of Christian missionaries and other outside influences.[279] While Alaskan religious masks were typically elaborate, those of the Canadian Inuit were comparatively simple.[280]

Gender expression

Inuit clothing was traditionally tailored in distinct styles for men and women, generally for functionality, but sometimes for symbolic reasons as well. For example, the shape of the kiniq, the frontal apron-flap of the woman's parka, was a symbolic reference to childbirth.[281] However, there is evidence from oral tradition and archaeological findings that biological sex and gendered clothing was not always aligned.[282] Some clothing worn by male angakkuit, particularly among the Copper Inuit, included design elements generally reserved for women, such as kiniq, symbolically bringing male and female together.[283][284] In some cases, the gender identity of the shaman could be fluid or non-binary, which was reflected in their clothing through the use of both male and female design elements.[271]

In some areas of the Canadian Arctic, such as Igloolik and Nunavik, there was historically a kind of gender identity known as sipiniq[lower-alpha 4] ("one who had changed its sex").[287] People who were born sipiniq were believed to have changed their physical sex at the moment of birth. Female-bodied sipiniit were socially regarded as male, would perform a male's tasks, and would wear clothing tailored for such tasks.[287] The gender of a child's clothing might be altered temporarily for other spiritual reasons. In some places, if one son in a family died, a surviving son might be dressed as a girl to disguise him from evil spirits.[250]

Cultural identity and art

The spiritual, personal and social text stitched into footwear designs are difficult or impossible to understand from objects removed from their makers or wearers.

Jill E. Oakes[288]

Today, the production and use of traditional skin clothing is increasingly important as a visual signifier of a distinct Inuit identity.[289][290][291] Engaging in traditional cultural practices like clothesmaking is strongly correlated with happiness and well-being among Inuit families and communities.[292] Wearing skin clothing can communicate one's cultural affiliation to Inuit culture in general or to a specific group.[293] Decorated kamiit are regarded as an important symbol of Inuit identity and a uniquely female art.[294] The amauti is also considered symbolic of Inuit women and motherhood.[23][295] Issenman describes the continued use of traditional fur clothing as not simply a matter of practicality, but "a visual symbol of one's origin as a member of a dynamic and prestigious society whose roots extend into antiquity."[296]

The decline in the use of traditional clothing coincided with an uptick in artistic depictions of traditional clothing in Inuit art, which has been interpreted as a reaction to a feeling of cultural loss.[297] Some artists have explored the effect of climate change on the use of traditional clothing, including sculptor Manasie Maniapik, and painter Elisapee Ishulutaq, who includes skin clothing in her works to represent "continuity in identity".[298] Other artists have examined the connection of sewing to motherhood.[299][300]

History

The history of Inuit clothing extends far back into prehistory, with significant evidence to indicate that the basic clothing structure has changed little since. The clothing systems of all indigenous Arctic peoples are structurally similar, and evidence in the form of tools and carved figurines indicates that these systems may have been in use in the Mal'ta–Buret' culture of Siberia as early as 22,000 BCE, and in the Pre-Dorset and Dorset cultures in Canada and Greenland as early as 2500 BCE.[301][302] Occasionally, pieces of garments are found at archaeological sites, mostly dating from the Thule culture era of approximately 1000 to 1600 CE.[303] Examples include the fully dressed 15th-century mummies found at Qilakitsoq in 1972, as well as the garments found at Utqiaġvik, Alaska in the early 1980s.[304] Structural elements of these remnants are very similar to garments from the 17th to mid-20th centuries, which confirms significant consistency in construction of Inuit clothing over centuries.[305][306]

Beginning in the late 1500s, contact with non-Inuit traders and explorers began to have an increased influence on the construction and appearance of Inuit clothing.[9] Imported tools and fabrics became integrated into the traditional clothing system, and premade fabric garments sometimes replaced traditional wear.[129][130][307] Adoption of fabric garments was often driven by external forces: missionaries found Inuit traditional garments inappropriate, and traders provided incentives for Inuit to sell the furs they hunted rather than use them themselves.[55][308] Inuit also adopted fabric garments for their own convenience, especially men who took work on whaling ships.[7][227] These voluntary adoptions often precluded the decline of traditional styles, as the use of manufactured clothing became associated with wealth and prestige.[29][309][310]

.jpg.webp)

Increased cultural assimilation and modernization at the beginning of the 20th century led to reduced production of traditional skin garments for everyday use. The introduction of the Canadian Indian residential school system to northern Canada disrupted the cycle of elders passing down knowledge to younger generations informally.[311][312] Even after the decline of the residential schools, most day schools did not include material on Inuit culture until the 1980s.[313][314]

Demand for skin garments shrank with lifestyle changes, including wider availability of manufactured clothing, which can be easier to maintain.[296][315] Overhunting depleted many caribou herds, and opposition to seal hunting from the animal rights movement crashed the export market for seal pelts; there was a corresponding drop in hunting as a primary occupation.[84][316][317] Reduced demand meant that fewer practitioners retained their skills, and even fewer passed them on.[313] By the mid-1990s, the skills necessary to make Inuit skin clothing were in danger of being completely lost.[318][85]

Since that time, Inuit groups have made significant efforts to integrate traditional sewing skills into modern Inuit culture, and cultural material is now taught in many northern schools and cultural literacy programs.[319][320] Sewing is now seen by many as a method for connecting with Inuit culture.[321] Incorporating modern techniques and purchasing materials commercially reduces the time and effort needed for garment production, lowering barriers for entry.[322][323] Although full outfits of traditional skin clothing are uncommon in day-to-day life, they may still seen in the winter and on special occasions.[84][88]

Many Inuit seamstresses today use modern materials to make traditionally styled garments, particularly amauti.[26][296][324] Since the 1990s, some seamstresses have begun to create fashionable garments for sale to consumers, supporting contemporary Inuit fashion as its own style within the larger indigenous American fashion movement.[325][326] In light of the growing interaction between Inuit clothing and the fashion industry, Inuit groups have raised concerns about the protection of Inuit heritage from cultural appropriation and prevention of genericization of cultural garments like the amauti.[327][328][329]

Research and documentation

There is a long historical tradition of research on Inuit clothing across many fields. Since Europeans first made contact with Inuit in the 15th century, documentation and research on Inuit clothing has included artistic depictions, academic writing, studies of effectiveness, and the collection of artifacts for museums.

Historically, European images of Inuit were sourced from the clothing worn by Inuit who travelled to Europe (whether voluntarily or as captives), clothing brought to museums by explorers, and from written accounts of travels to the Arctic. The earliest of these was a series of illustrated broadsides printed after an Inuit mother and child from Labrador were brought to the European Low Countries in 1566.[330] Other paintings and engravings of Inuit and their clothing were created over the following centuries.[331] 19th century techniques such as photography allowed for a wider dissemination of images of Inuit clothing, especially in illustrated magazines.[331]

From the 18th century until the mid-20th century, explorers, missionaries, and academics described the Inuit clothing system in memoirs and dissertations.[332][333] After a decline in the 1940s, serious scholarship of Inuit clothing did not pick up again until the 1980s, at which time the focus shifted to in-depth studies of the clothing of specific Inuit and Arctic groups, as well as academic collaborations with Inuit and their communities.[333][334][335] Inuit clothing has also been extensively studied for its effectiveness as cold-weather clothing, especially as compared to synthetic materials.[336][337] Microscopic analysis of historical garments can reveal details about the animal that produced the pelt, including genetic information from DNA and dietary information from carbon and nitrogen isotopes.[338]

Many museums, particularly in Canada, Denmark, the United Kingdom, and the United States, have extensive collections of historical Inuit garments, often acquired during Arctic explorations undertaken in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[339] The British Museum in London holds some of the world's oldest surviving Inuit fur clothing, and the collection of the National Museum of Denmark is one of the most extensive in the world.[340][341][342]

Gallery

Niviatsinaq, companion of George Comer, in her elaborate beaded parka, c. 1903–1904

Niviatsinaq, companion of George Comer, in her elaborate beaded parka, c. 1903–1904.jpg.webp) Long "Mother Hubbard" style parka, Alaskan Inuit, acquired 1926

Long "Mother Hubbard" style parka, Alaskan Inuit, acquired 1926 Men's seal fur gloves, sealskin palm and trim, east Greenlandic Inuit, acquired 1940

Men's seal fur gloves, sealskin palm and trim, east Greenlandic Inuit, acquired 1940%252C_Kinngait%252C_Nunavut_(31497043966).jpg.webp) Inuit woman chewing hide to soften it, 1946

Inuit woman chewing hide to soften it, 1946 Modern Kalaallit formal women's outfit with beadwork collar, and avittat or skin embroidery at the ends of the sleeves, acquired 1979

Modern Kalaallit formal women's outfit with beadwork collar, and avittat or skin embroidery at the ends of the sleeves, acquired 1979 Two Inuit women wearing modern cloth amautiit (woman's parka, skirted style), Nunavut, 1995

Two Inuit women wearing modern cloth amautiit (woman's parka, skirted style), Nunavut, 1995

Women's qarlikallaak, or short trousers from Greenland, collected by Robert Peary by 1908

Women's qarlikallaak, or short trousers from Greenland, collected by Robert Peary by 1908.jpg.webp) Three Iñupiat women wearing traditional long parkas. The woman in the centre has qupak trim, a traditional geometric style, around her hem. Seattle, 1911.

Three Iñupiat women wearing traditional long parkas. The woman in the centre has qupak trim, a traditional geometric style, around her hem. Seattle, 1911.%252C_Copper_Eskimo%252C_collected_in_1920-1921_-_Native_American_collection_-_Peabody_Museum%252C_Harvard_University_-_DSC05652.JPG.webp) Woman's Copper Inuit parka in the traditional style with exaggerated shoulders, Peabody Museum, acquired 1920–1921

Woman's Copper Inuit parka in the traditional style with exaggerated shoulders, Peabody Museum, acquired 1920–1921_to_dry%252C_Pangnirtuuq_(Pangnirtung)%252C_Nunavut_(30726111653).jpg.webp) Inuit woman hanging kamiit boots to dry, Pangnirtuuq, Nunavut, 1951

Inuit woman hanging kamiit boots to dry, Pangnirtuuq, Nunavut, 1951 Pair of wet-weather kamiit boots and tools for sewing kamiit. Note wrap-around sole, seam location, and lack of laces (close-up).Ungava, 1989.

Pair of wet-weather kamiit boots and tools for sewing kamiit. Note wrap-around sole, seam location, and lack of laces (close-up).Ungava, 1989. Contemporary men's dress shoes made with undyed ringed seal fur, by Nicole Camphaug, 2021

Contemporary men's dress shoes made with undyed ringed seal fur, by Nicole Camphaug, 2021

Notes

- ↑ Inuktitut syllabics were standardized in 1976 by the now-defunct Inuit Cultural Institute to reflect the Romanized spelling of Inuktitut words.[13][14]

- ↑ Kamiit is the Eastern Arctic term for boots, and mukluk is the Western Arctic equivalent. While there are some stylistic differences between them, they are functionally the same. This article refers to all Inuit boots as kamiit for consistency. The singular form of kamiit is kamik.[47]

- ↑ Plural form angakkuit[271]

- ↑ Plural form sipiniit; the Netsilik Inuit used the word kipijuituq for a similar concept[285][286]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Issenman 1997, p. 43.

- 1 2 Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 27.

- ↑ Osborn 2014, pp. 48–49.

- 1 2 Stenton 1991, p. 9.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Issenman 1997, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Buijs 2005, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 Martin 2005, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4 Issenman 1997, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hall 2001, p. 117.

- ↑ Oakes 1991, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Stenton 1991, p. 7.

- ↑ Bell 2019.

- ↑ Pirurvik Centre n.d.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, p. 19.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, pp. 34–36.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, pp. 43–44.

- 1 2 3 4 Pharand 2012, p. 15.

- ↑ Hall 2001, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Issenman & Rankin 1988a.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, p. 44.

- ↑ Rholem 2001, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ryder 2017.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Rholem 2001, p. 46.

- 1 2 Pharand 2012, p. 26.

- ↑ Issenman 2007, Slide 24.

- 1 2 3 Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Issenman 1997, pp. 108, 117.

- ↑ Atkinson 2017.

- ↑ Cresswell 2021.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 Pharand 2012, p. 29.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Issenman 2007, Slide 3.

- ↑ Buijs 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, p. 30.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Hall 2001, pp. 131–132.

- 1 2 3 Issenman 1997, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 20.

- 1 2 Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 51.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, pp. 50, 54, 60.

- 1 2 Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 79.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, p. 86.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 104.

- ↑ Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 83.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 85.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, pp. 113, 133.

- ↑ Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 Schmidt 2018, p. 124.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, p. 47.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, pp. 47–50.

- ↑ Issenman 2007, Slide 4.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 12.

- ↑ Rholem 2001, p. 68.

- ↑ Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 133.

- ↑ Issenman & Rankin 1988b, pp. 135–137.

- 1 2 3 Petersen 2003, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Buijs 1997, p. 21.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 31.

- ↑ Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 116.

- ↑ Vancouver Maritime Museum n.d.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 48.

- 1 2 Nakashima 2002, p. 26.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, p. 40.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ Pharand 2012, pp. 22, 42.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, pp. 54–57.

- 1 2 Pharand 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, p. 215.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 146.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, pp. 101, 108.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, pp. 108–113, 115.

- ↑ Sponagle, Jane (30 December 2014). "Inuit parkas change with the times". CBC News. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 115.

- ↑ Rohner 2017.

- 1 2 3 Issenman 1997, p. 242.

- 1 2 Petrussen 2005, p. 47.

- ↑ Oakes 1987, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Rholem 2001, p. 32.

- 1 2 Oakes & Riewe 1995, pp. 19, 31.

- ↑ Pickman 2017, p. 35.

- 1 2 Stenton 1991, p. 4.

- 1 2 Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 34.

- ↑ Oakes 1991b, pp. 71–79.

- 1 2 3 4 Issenman 1997, p. 32.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Stenton 1991, p. 8.

- ↑ Oakes & Riewe 1995, pp. 96, 113, 171.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Issenman 1997, p. 40.

- ↑ Reed 2005, p. 48.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, p. 270.

- 1 2 Issenman 1997, pp. 40, 52.

- 1 2 Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 84.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, p. 171.

- ↑ Issenman 1997, pp. 98, 172.

- ↑ Inuktitut Magazine 2011, p. 14.

- 1 2 Issenman & Rankin 1988b, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 Hall 2001, p. 116.

- ↑ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 16.