Two missions of military intelligence collection, both of which came to a climax on 30 December 1776, contributed to the Continental Army's victory in the Battle of Princeton.

Joseph Reed and the Philadelphia Light Horse

The "obscure and doubtful" intelligence on which General Washington had to base his next action frustrated him after a decisive victory in the Battle of Trenton.[1] Washington observed to Adjutant-General Joseph Reed that the strength of the British in the area had greatly discouraged spies for the revolution;[1] Reed had the same opinion, having himself encountered the "poor" and "terrified" inhabitants of Bordentown only days before. Red rags hung from almost every house door in expression of Tory sympathies; homeowners were hastily tearing them down in accordance with the clear turn of events. Reed considered the residents "effectually broken and hardly resembling what they had been a few months before."[2]

Reed was a New Jersey native and proposed to Washington that he led a group of cavalrymen from the Philadelphia Light Horse toward Princeton to enlist spies. The Philadelphia Light Horse was a group of twenty-one wealthy young men that volunteered its service to General Washington. They paid their own expenses, and, unlike most Continental troops, were gentlemen. The Light Horse wore chocolate brown uniforms, high-topped riding boots, and black hats with silver cords and bucktails. David Hackett-Fischer speculates that ragged Continental infantrymen jeered them as they approached Trenton on matched chestnut horses.[3]

Washington approved the mission, and sent Reed with seven cavalrymen.[1] The residents on the road to Princeton, however, were afraid. In Reed's words, the "arms and ravages of the enemy" had terrified the population; though they were "otherwise well disposed," no reward could tempt them to go into Princeton on a mission of espionage.[1] Stories of captured revolutionaries who were starving in the prison hulks of New York, along with more immediate accounts of British plunder and rape in New Jersey, were doubtlessly a strong deterrent to participation in the cause of the Continental Army.[4]

Reed and his men were determined to return with valuable information. Expecting that the rear of Princeton would be poorly guarded, they circled the town.[1] They were about a half-mile southeast of Clarksville,[5] almost in view of Princeton itself, when they spotted a British soldier walking between a barn and a house. Reed assumed he was looting, and sent two cavalrymen to take him prisoner.[1] The Light Horsemen kept the barn between themselves and the house to approach closely without being noticed.[5]

A second and third soldier appeared as they rode, and Reed ordered the rest of his men to charge.[1] As things worked out, Reed's men were outnumbered, but they were also in the right place at the right time. Most of the twelve British soldiers were busy "conquering a parcel of mince pies" as the Light Horse surrounded the house.[6] Seven cavalrymen, six of whom had "never before seen an enemy," thus forced the surrender of twelve well-armed British dragoons.[7]

Reed and the Light Horse returned to Trenton with their captives mounted behind, probably to a much different reception by Continental infantrymen.[6] The prisoners were separately interrogated, and revealed that General Grant had reinforced British troops at Princeton, that the force assembled there comprised over 8,000 trained soldiers, and that the British intended to advance on Trenton. This was critical intelligence; at the time, Washington commanded only 4,700 men, many of whom were new recruits, and all of whom were poorly equipped.[8]

"A Very Intelligent Young Gentleman"

On 12 December, Washington had written a letter to Colonel John Cadwalader, the senior officer of a militia called the Philadelphia Associators. This letter emphasized what Washington understood as an imminent necessity for both intelligence and counterintelligence.

Spare no pains or expense to get intelligence of the enemy’s motions and intentions. Any promises made, or sums advanced, shall be fully complied with and discharged... Every piece of intelligence you obtain worthy of notice, send it forward by express... Keep a good lookout for spies, and magnify your numbers as much as possible.[9]

Three days after receiving these orders, Cadwalader replied that he had sent "several persons over for intelligence."[10] Two weeks later, on the morning of 31 December, he identified one of his spies, "a very intelligent young gentleman" who had just returned from Princeton with details on the British force and its disposition.

...there were about five thousand men, consisting of Hessians and British troops—about the same number of each... He conversed with some of the officers, and lodged last night with them... No sentries on the back or east end of the town. They parade every morning an hour before day, and some nights lie on their arms. An attack has been expected for several nights past—the men are much fatigued, and until last night [were] in want of provisions, when a very considerable number of wagons arrived with provisions from Brunswick...[11]

In accordance with Washington's orders, the spy magnified the Continental Army's numbers, telling them the best accounts reported 16,000 troops. This surprised the British, who had expected no more than five or six thousand.[12]

The same young gentleman, by coincidence, was "near the party of chasseurs" when they were captured by Reed and the Light Horse, and was with the British officers when they received news of the attack.[12]

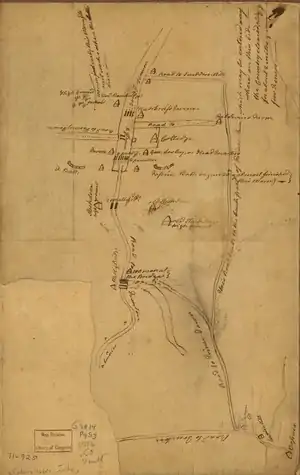

Cadwalader included with his letter a "rough draft of the road from this place," meaning from Crosswicks, where Cadwalader was at the time, to Princeton. The map was highly detailed. Cadwalader put numbers next to bridges, for example, to indicate the number of soldiers defending them. A block of text perpendicular to the others ran up and down the right side of the map, highlighting a road: "This road leads to the back part of Princeton which may be entered anywhere on this side—the country cleared, chiefly, for about 2 miles... few fences."[13] The map was particularly helpful in that it displayed not what existed at the time Cadwalader drew it up, but what would exist by the time General Washington could act on the intelligence it provided. In other words, the map was estimative, indicating "works begun, and those intended this morning."[5]

Before he heard from Cadwalader, Washington had only three pieces of intelligence, all of which were ascertained through prisoner interrogation: firstly, that General James Grant had reinforced British troops at Princeton; secondly, that the aggregate force there comprised over 8,000 soldiers; and thirdly, that they intended to advance on Trenton. It is likely that Cadwalader's report, obtained from a plainclothes spy who ingratiated himself with British officers, relieved Washington both by suggesting a substantially weaker enemy force of around 5,000 men and by providing detailed, actionable information on their positions and disposition.

Washington immediately sent a large Continental force up the Post Road with orders to delay any British movement toward Trenton. It advanced under the cover of darkness on New Year's Eve, occupying a position six miles from Nassau Hall. The British spotted them at dawn and sent its First Battalion light infantry, along with two Hessian companies to engage the revolutionaries. The British cleared the road, but at a heavy cost.[14]

St. Clair's Proposal

On 2 January 1777, British troops advanced in force; the Continental Army held its ground at Assunpink Creek in the Second Battle of Trenton. That evening, Washington convened a council of war. His senior officers, including Reed and Cadwalader, were there, along with local citizens whom Washington invited both to attend the meeting and to speak freely.[15]

Washington's officers considered several alternatives, none of which seemed advantageous. General Arthur St. Clair proposed a surprise attack on the enemy's rear; if Continental troops could reach Quaker Bridge unobserved and unopposed, he argued, they would only have to proceed north about six miles before reaching Princeton. Reed confirmed this estimate and contributed his own knowledge of the terrain. When he led the Light Horse to Princeton, he mentioned, they saw no British on the back roads. One officer later recalled that "two men from the country, near the route proposed," were "called to the council for their opinions of its practicability."[16]

St. Clair's idea was bold. Washington might have rejected it outright had it not been for the additional intelligence he was able to solicit from ordinary colonists on the evening of 2 January.

Aftermath

When Washington wrote John Hancock three days later, on 5 January 1777, it was with good news.

To John Hancock

Pluckamin [N.J.] January 5th 1777Sir

I have the honor to inform you, that, since the date of my last from Trenton, I have removed with the army under my command to this place. ... Their large pickets advanced towards Trenton, their great preparations, and some intelligence I had received, added to their knowledge, that the 1st of January brought on a dissolution of the best part of our army, gave me the strongest reasons to conclude, that an attack upon us was meditating.[17][18]

Washington described the Continental Army's march to Princeton, "by a roundabout road," as its baggage was quietly moved to Burlington.[19] The Battle of Princeton was a decisive victory for Continental troops, which took the British force by surprise.[20] This was just the pick-up colonists needed; The Pennsylvania Journal wrote that if Washington had lived in the days of idolatry, he would have been worshiped as a god.[20]

Washington formally discharged the Philadelphia Light Horse three weeks later, saying that "though composed of gentlemen of fortune," they had "shown a noble example of discipline and subordination," and in several actions had "shown a spirit and bravery which will ever do honor to them, and will ever be gratefully remembered by me."[21] In September 1779, the Light Horse reconvened at Washington's own request and served the Continental Army until the British surrender at Yorktown two years later, in October 1781.[22]

The Philadelphia Light Horse enjoyed an honorable legacy after the American Revolution. In his 1816 memoir, General Wilkinson praised the cavalrymen for their 30 December expedition. This "little act of decisive gallantry" had "tended to increase the confidence of the troops, and certainly reflected high honor on the small detachment."[23] Eight years later, at a reception held for General Lafayette, John Lardner and William Leiper—the sons of two Light Horse cavalrymen who were part of the reconnaissance mission—wore the gorgets of British officers captured that day.[24]

Published in 1875, the Light Horse's narrative of the 30 December expedition cooperates almost perfectly with that of Joseph Reed. The sole discrepancy is the number of men that Reed took with him. The Light Horse maintains that Reed took twelve, not seven, cavalrymen with him on the mission to Princeton,[25] while Reed clearly asserts in his handwritten account that he proceeded on that day "with seven gentlemen," five of whom he names: Messrs. Caldwell, Dunlap, Hunter, Pollard, and Peters.[1] Assuming that the two others are Messrs. Lardner and Leiper, five men of the Light Horse's narrative remain unaccounted for.

Whether Reed excluded, by accident or by design, the names of men that accompanied him on such a vital mission, or whether members of the Light Horse sought credit, ex post facto, for a mission with which they were not involved, is unclear. History seems to have sided with the Light Horse; most accounts of the expedition mention twelve, not seven cavalrymen. A notable exception is David Hackett Fischer’s Washington's Crossing, which—perhaps nodding to the discrepancy—avoids the mention of a figure.

The legacy of the Philadelphia Light Horse stands in stark contrast to that of Cadwalader's anonymous and "intelligent young gentleman." He might have been a student at Princeton, which had been closed since the British invasion.[26] It is likely that he had no surviving family; none claimed his story after the war or since.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Reed’s Narrative p.399

- ↑ Reed’s Narrative p.397

- ↑ Fischer p.279

- ↑ Solis p.13

- 1 2 3 Life and Correspondence p.283

- 1 2 Fischer p.280

- ↑ Reed’s Narrative p.399-400

- ↑ First Troop p.9

- ↑ Davis p.140

- ↑ Washington’s Spies, Chapter Two

- ↑ Life and Correspondence p.283-4

- 1 2 Life and Correspondence p.284

- ↑ Cadwalader

- ↑ Fischer p.281-2.

- ↑ Fischer p.315

- ↑ Fischer p.314-5.

- ↑ Washington p.146-7

- ↑ "From George Washington to John Hancock, 5 January 1777". National Historical Publications & Records Commission.

- ↑ Washington p.148

- 1 2 Flexner p.189

- ↑ Muster-roll p.15

- ↑ Muster-roll pp.16, 25

- ↑ Wilkinson pp.133–34

- ↑ First Troop p.9n

- ↑ First Troop p.8

- ↑ Fischer p.281

References

- By-laws, Muster-roll, and Papers Selected from the Archives of the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry: from November 17, 1774, to March 1, 1856. (1856). James B. Smith.

- Cadwalader, J. (1776). Plan of Princeton, Dec. 31, 1776. Retrieved January 3, 2011, from http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/h?ammem/gmd:@field%28NUMBER+@band%28g3814p+ct000076%29%29

- Davis, W. (1880). Washington on the West Bank of the Delaware, 1776. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 4 (2), 133–163.

- Fischer, D. H. (2006). Washington's Crossing. Oxford University Press US.

- Flexner, J. (1968). George Washington in the American Revolution. Boston: Little and Brown.

- History of the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry: from its Organization, November 17th, 1774 to its Centennial Anniversary, November 17th, 1874. (1875). Philadelphia: Hallowell.

- Reed, J. (1880). General Joseph Reed's Narrative of the Movements of the American Army in the Neighborhood of Trenton in the Winter of 1776–77. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 8 (1), 391–402.

- Reed, W. B. (1847). Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed: Military Secretary of Washington, at Cambridge; Adjutant-General of the Continental Army; Member of the Congress of the United States; and President of the Executive Council of the State of Pennsylvania. Lindsay and Blakiston.

- Rose, A. (2006). Washington's Spies: The Story of America's First Spy Ring. New York: Bantam Books.

- Solis, G. D. (2010). The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War. Cambridge University Press.

- Washington, G. (1890). The Writings of George Washington. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Wilkinson, J. (1816). Memoirs of My Own Times. Printed by Abraham Small.