.jpg.webp)

The ideology of the Schutzstaffel ("Protection Squadron"; SS), a paramilitary force and an instrument of terror of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, emphasized a racist vision of "racial purity", primarily based on antisemitism and loyalty to Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany.

SS men were indoctrinated with the belief they were members of a "master race". The ideology of the SS was, even more so than in Nazism in general, built on the belief in a superior "Aryan race". This led to the SS playing the main role in political violence and crimes against humanity, including the Holocaust and "mercy killing" of those with congenital illnesses. After the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II, the SS and Nazi Party were found to be criminal organizations at the Nuremberg Trials.

Ideological foundations

The ideology of the SS was built upon and mainly congruent with Nazi ideology. At its center laid the belief in a superior "Nordic race" and the "inferiority" of other races.[2] The SS itself had four principal mythologies built into their intellectual edifice; these were blood (Blut), soil (Boden), ancestors (Ahnen), and kin (Sippe).[3] For the SS, their perception of Germanic ethnicity was based on Hans Günther's theories of the Nordic race, members of which were alleged to possess particularly desirable mental and physical characteristics. These were tied to the natural environment from where they derived, a climate that imbued them with special cultural features atop a certain "hardness" and "combat readiness."[3] Since these Germanic ancestors had "spread across many countries" over the centuries, Himmler's vision was to conquer areas previously belonging to them so as to bring together this pan-Germanic community once again. Re-acquiring these territories was viewed by the SS as its mission, beyond traditional nation-state imperialism, in order to convert these regions into agriculturally focused communities and create an organic utopia, "a close-knit community bound by blood and soil."[4]

This racially aligned community, based on SS "blood and soil" ideology, was linked with the "idealization" of their ancestors, making their worldview likewise "historically oriented and retrospective."[5] Ancient Germanic peoples formed prototypes for maintaining social cohesion under exclusivist racial auspices, since they were unlike their modern descendants that had been exposed to "racial interbreeding."[5] Therein, an "ancestral inheritance" (Ahnenerbe) was ascribed to these predecessors, who were thought to possess a "suprahistorical source of wisdom"; they were likewise mythologized for their military prowess, providing the SS with inspiration and exemplary heroes to emulate.[5] The SS ideology further linked this "ancestral heritage" with a collectivist notion of racial kinship, which SS members were taught to protect, being members of an "Order of the Race" (Sippenorden).[5]

To this end, the SS served as the central institution for the broader extension of Nazi ideology and its realisation.[6] Representing the ideological opponents of the regime in one form or fashion, historian George C. Browder identified the Nazi state's list of enemies as follows: enemy states, miscegenation, the Jews, Catholicism, freemasonry, Communism, the Republic (hostility directed at the liberal republican constitution and form of government), homosexuality,[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] moral decay, capitalists, and the "Old Guard" (hate and fear of traditionally powerful influences and institutions of the old society as unjust, retarding influences in German society).[9] These groups became the focus of the SS—the predominant instrument of power for the Nazi totalitarian state—as they sought to direct and influence ideology and ethics within the Reich.[10]

Beginning as early as 1933, the leadership of the SS and the police organizations in Nazi Germany showed a "high-degree of interest in ideological indoctrination," since the SS leader, Heinrich Himmler was "convinced that weltanschauliche Erziehung (ideological education) was key to the coherence and effectiveness of his growing SS and police apparatus."[11] One of the primary functions Himmler foresaw to this end was the power of ideology and indoctrination to prepare members of the SS to effectively police German society and extirpate the nation of its "enemies."[12] Ideological training was designed to foster an attitude of "energetic ruthlessness, self-conscious determination," and the ability to adjust to any situation.[12] Himmler intended for the SS to be a hierarchical system of "ideological fighters" from the organization's inception.[13] The SS proved to be that and more, becoming the instrument most responsible for the actualization of Nazi beliefs. SS ideology comprised perhaps the single most significant philosophical dimension of Nazism, employing ontological, anthropological, and ethical elements to their methods under the guise of science, shaping the Nazi state's doctrine and crystallizing ideals (no matter how callous) into dogmatic truths. SS principles and thinking provided pseudo-scientific rationales for the devaluation of humanity, and ideological justification for Nazi violence and genocide.[14]

The SS placed an intense emphasis in their indoctrination upon elitism and portrayed themselves as part of an "elite" order which "explicitly modelled [themselves] on an historical version of religious orders, such as the Teutonic Knights or the Jesuits, whose dedication to a higher idea was admired in these otherwise anti-clerical circles".[15][16]

Indoctrination

The strict training program was focused on the fundamental ideological principles of the Nazi Party, namely the belief in a "superior Nordic race", loyalty and absolute obedience to Adolf Hitler, and hatred for those who were considered "inferior people", with great emphasis on antisemitism.[17][18] Students studied the most anti-Semitic passages of Mein Kampf ("My Struggle"), Hitler's autobiographical manifesto, and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fraudulent anti-Semitic document first published in Russia in 1903, which purported to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The SS educational leaders were also responsible for general anti-religious training,[19] which was part of the Nazi attempt at "reversing the bourgeois-Christian system of values."[20] Educational training was clearly linked with "racial selection, at the end of which stood the 'weeding out' and selective breeding of human beings"; this facet coincided the impending Nazi effort to Germanize Europe and formed part of the policy for the racial-imperialist conquest in the East.[21]

Following the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, membership in the SS grew considerably, prompting an increase in ideological instruction. The SS-Schulungsamt took over the task of heading the educational matters of the SS, led by Karl Motz.[22] The SS published two additional magazines for ideological propaganda: the monthly FM-Zeitschrift, funded by 350,000 non-member financial patrons of the SS, and the weekly Das Schwarze Korps, the second biggest weekly paper in Nazi Germany.[23] As part of an effort to professionalize their officers, the SS founded a Leadership School in 1934 at the Bavarian town of Bad Tölz; a second school was established at Braunschweig—these came to be known as SS-Junker Schools.[24][lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4]

Beginning in 1938, the SS intensified the ideological indoctrination of the Hitler-Jugend Landdienst ("Hitler Youth Land Service"). It set out the ideal of the German "Wehrbauer" ("Soldier Peasant"). Special high schools were created under SS control to form a Nazi agrarian "elite" that was trained according to the principle of "blood and soil".[28] While SS leader Heinrich Himmler remained concerned about the racial elitism of his SS, it was Reinhard Heydrich, Himmler's deputy and protégé, who focused his attention on their political indoctrination through the creation of "racial detectives" who would become Hitler's "ideological Shock Troops".[29] This being done through the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service; SD) which was tasked with the detection of actual or potential enemies of the Nazi leadership and the neutralization of any opposition. The SD used its organization of agents and informants, all part of the development of an extensive SS state and a totalitarian regime without parallel.[30]

The SS practiced a wide variety of disciplinary measures, with punishments composed of reprimands, prohibition to wear the uniform, detention, demotion, suspension, and expulsion. Contrary to claims made by many SS-members after 1945, no one had to fear being incarcerated in a concentration camp for delinquencies. Starting in June 1933, the SS had its own courts to deal with crimes and misdemeanors within its ranks. On 17 October 1939, Himmler succeeded in having the SS put under its own special jurisdiction. Once this change occurred, SS-members could no longer be tried in civil courts.[31][32] Even though Himmler and the other SS leaders repeatedly demanded sobriety within their ranks, alcoholism was a frequent problem. For example, between 1937 and 1938 some 700 members were excluded from the SS for "listlessness and laziness." In the same period a further 12,000 left the SS for unknown reasons, calling into question the institution's claims of "loyalty for life".[33]

Meritocracy

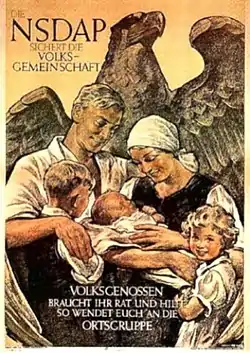

The SS itself was meritocratic in its general operational structure, following the Nazi principle of Volksgemeinschaft.[34] In contrast to the German army's traditions, officer promotions in the SS were based on the individual's commitment and political reliability, not on Junker status or upper-class family background.[35][36] Consequently, the SS officer schools offered a military career option for those of modest social background, which was not usually possible in the Wehrmacht. The relationship between officers and soldiers was also less formal than in the regular armed forces.[37] Though SS membership was open to all who met Himmler's eugenic and genealogical standards, many of the men first to enter the SS came from the aristocracy.[38] In addition, academics were twofold over-represented in the SS in comparison to the general population.[39]

Racial policies

Consistent with the eugenic and racial policies of the Third Reich, Himmler advocated racial elitism for his SS members.[40] Racial criteria like proving pure "Aryan" lineage back to 1750 or 1800 constituted part of the vetting for entrance into the SS.[41] Throughout the existence of the SS, its members were regularly encouraged to procreate to maintain and increase the "Aryan-Nordic bloodline"; the SS members, along with their wives and children, were to become an exclusive racial community (Sippengemeinschaft) within the Nazi state. Along these lines, Himmler stated on 8 November 1937 at a Gruppenführer meeting in Munich in the officers' quarters:

The SS is a National Socialist order of soldiers of Nordic race and a community of their clans bound together by oath ... what we want for Germany is a ruling class destined to last for centuries and the product of repeated selection, a new aristocracy continuously renewed from the best of the sons and daughters of our nation, a nobility that never ages, stretching back into distant epochs in its traditions, where these are valuable, and representing eternal youth for our nation.[42]

Similarly, Himmler drew an analogy between the Nordic race and Bolshevism and argued during a speech that the triumph of Bolshevism would mean the extermination of the Nordic race.[43] He also believed that once the SS had succeeded in being a racially pure organisation then other Germans would naturally join the SS.[43] Correspondingly, SS men were indoctrinated with anti-Slavic beliefs.[43]

Hitler subscribed to these views and once remarked that the "elite" of the future Nazi state would stem from the SS since "only the SS practices racial selection."[44] Wives of SS members were scrutinized accordingly for their "racial fitness", and marriages had to be approved through official channels as part of the SS ideological mandate.[45] According to their ideology, SS men were believed to be the bearers of the very best of the so-called Nordic blood, and it was their ideological tenets and scholarly justifications that shaped numerous Nazi actions and policies, merging racial determinism, Nordicism, and antisemitism.[46]

An SS Doctors' Leader School was established in the small village of Alt-Rehse which encouraged the practice of "racial hygiene" and focused on the future of "German genetic streams" (deutsche Erbströme).[47] Medical journal articles written by SS intellectuals stressed the importance of genetic heritage, arguing that "biology and genetics are the roots from which the National Socialist worldview has derived its knowledge, and from which it continues to derive new strength."[48] In order to promote its role as a preserver of Germanic heritage, the SS founded the Ahnenerbe institute in 1935. It conducted anthropological, historical, and archeological studies to provide "scientific" backing for Himmler's ideals. From its founding until 1939, the institute commissioned studies on places like the Viking village Hedeby, and even conducted erratic studies into medieval witch-hunts; Himmler believed these witch-hunts were murders committed by the Roman Catholic Church against Germanic women of "good blood". After World War II started, the Ahnenerbe was heavily involved in medical experiments conducted at concentration camps—many of these experiments were cruel and inhumane, costing the lives of thousands of inmates.[49]

Not only was contact with racial "others" a concern of the SS and its agencies, but attrition through war was an additional factor. Fear of losing a large percentage of Germanic racial stock once the Second World War began drove SS ideology, as victory in the field could not prevail without a corresponding biological legacy of children to carry on the mission.[50] Himmler stressed that SS men were obliged to procreate to preserve Germany's genetic legacy so the "master race" could secure and sustain the "Thousand Year Reich" of the future.[51]

However, SS men did not fulfill the expectations: at the end of 1938, 57% of the members were still unmarried, only 26% had fathered a child and just 8% had reached Himmler's desired goal of at least four children.[52] Also in 1935, the SS initiated Lebensborn, an association created to provide unmarried, pregnant women of "good blood" with opportunities to deliver their children, who were then given up for adoption into families deemed racially suited. The Lebensborn facilities were situated in remote locations, guaranteeing the anonymity of the women. Lebensborn was only moderately successful, producing only an estimated 8,000 - 11,000 births in the ten years of its existence.[53]

After the beginning of World War II, the SS recruited large numbers of non-Germans from the "inferior races" espoused by the Nazi and SS ideology. To justify this contradiction, Himmler began to stress a shared European identity more strongly in the early 1940s, promising that "all those who are of good blood will be given the possibility to grow into the German Volk".[54] According to historian Mark P. Gingerich, of the one million Waffen-SS men who served during the war, over half were not even German citizens.[55]

Attitude toward religion

According to Himmler biographer Peter Longerich, Himmler saw a main task of the SS to be that of "acting as the vanguard in overcoming Christianity and restoring a Germanic way of living" as part of preparations for the coming conflict between "humans and subhumans".[56] Longerich writes that, while the Nazi movement as a whole launched itself against Jews and Communists, "by linking de-Christianisation with re-Germanization, Himmler had provided the SS with a goal and purpose all of its own."[56] Himmler was vehemently opposed to Christian sexual morality and the "principle of Christian mercy", both of which he saw as a dangerous obstacle to his planned battle with "subhumans".[56] In 1937, he said that the movement was an era of the "ultimate conflict with Christianity" and that "It is part of the mission of the SS to give the German people in the next half century the non-Christian ideological foundations on which to lead and shape their lives."[57]

The SS developed an anti-clerical agenda. Chaplains were not allowed in its units for instance (although they were allowed in the regular army). The Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service; SD) department of the SS and Gestapo under Reinhard Heydrich were used to identify and assist other Nazi organizations in suppressing Catholic influence in the press, youth clubs, schools, publications, and in discouraging pilgrimages and religious processions.[58]

Himmler used the Jesuits as the model for the SS, since he found they had the core elements of absolute obedience and the cult of the organisation.[59][60] Hitler is said to have called Himmler "my Ignatius of Loyola".[59] As an order, the SS needed a coherent doctrine that would set it apart.[61] Himmler attempted to construct such an ideology, and deduced a "pseudo-Germanic tradition" from history.[61] Himmler dismissed the image of Christ as a Jew and rejected Christianity's basic doctrine and its institutions.[62] Starting in 1934, the SS hosted "solstice ceremonies" (Sonnenwendfeiern) to increase team spirit within their ranks.[63] In a 1936 memorandum, Himmler set forth a list of approved holidays based on pagan and political precedents meant to wean SS members from their reliance on Christian festivities.[64] In an attempt to replace Christianity and suffuse the SS with a new doctrine, SS-men were able to choose special Lebenslauffeste, substituting common Christian ceremonies such as baptisms, weddings and burials. Since the ceremonies were held in small private circles, it is unknown how many SS-members opted for these kind of celebrations.[65]

Rejection of Christian precepts

Many of the concepts promoted with the SS violated accepted Christian doctrine, but neither Himmler nor his deputy Heydrich expected the Christian church to support their stance on abortion, contraception or sterilization of the unfit – let alone their shared belief in polygamy for the sake of racial propagation.[66] This did not however represent disbelief in a higher power from either man nor did it deter them on their ideological quest. In fact, atheism was banned within the SS as Himmler believed it to be a form of egotism that placed the individual at the center of the universe, and thus constituted a rejection of the SS principle of valuing the collective over the individual.[67] All SS men were required to list themselves as Protestant, Catholic or gottgläubig ("Believer in God").[68] Himmler preferred the neo-pagan "expression of spirituality". Still, by 1938 "only 21.9 percent of SS members described themselves as gottgläubig, whereas 54 percent remained Protestant and just under 24 percent Catholic."[69] Belief in God among the SS did not constitute adherence to traditional Christian doctrine nor were its members consummate theologians, as the SS outright banned certain Christian organizations like the International Bible Research Association, a group whose pacifism the SS rejected.[70] Dissenting religious organizations like the Jehovah's Witnesses were severely persecuted by the SS for their pacifism, failure to participate in elections, non-observance of the Hitler salute, not displaying the Nazi flag, and for their non-participation in Nazi organizations; many were sent to concentration camps where they perished.[71] Heydrich once quipped that any and all opposition to Nazism originated from either "Jews or politicized clergy."[72]

Neo-pagan doctrine

In order to promote his religious ideas and link them to an alleged Germanic tradition, Himmler began to establish cult sites. The most important of these was the Wewelsburg, close to Paderborn.[73] The SS leased the castle in 1934, after Himmler had first seen it in November 1933 while campaigning with Hitler. Originally planned as a school for high ranking SS-men, the castle soon became the object of far reaching construction plans, with an aim at establishing the Wewelsburg as the "ideological center" of the SS and its pseudo-Germanic doctrine.[74][75] In accordance with the other efforts of Himmler to replace Christian rituals and establish the SS as the Nazi "elite", the Wewelsburg received special rooms, such as crypts, a General's hall with a sun wheel embedded in the floor and a crest hall.[76] As a second location, Himmler ordered for a memorial of 4,500 standing stones to be placed near Verden an der Aller, the scene of the infamous Massacre of Verden in 782, calling the place Sachsenhain (Saxon Grove). At the site of the Externsteine, which at the time was believed to be close to the scene of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, Himmler ordered excavations in order to prove that during the Middle Ages, Christian monks had destroyed a Germanic cult site known as an Irminsul. The SS also took over and remodelled Quedlinburg Abbey, burial place of Henry the Fowler, who Himmler celebrated for his refusal to be anointed by a Roman bishop.[77]

Himmler instituted additional rites and rituals to try and foster a greater sense of belonging within the SS fraternal order. For example, each year on the anniversary of the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, SS men duty-bound for the military units were sworn in at 10:00 pm in front of Hitler. There by torchlight, they swore "obedience unto death".[78]

However, these attempts to establish a new, neo-pagan religion were unsuccessful. Historian Heinz Höhne observes that the "neo-pagan customs" Himmler introduced into the SS "remained primarily a paper exercise".[79] Most of Himmler's attempts to link "old Teutonic" traditions into the spiritual life of the SS and society at large were criticised by the Church as a form of "new heathenism."[80] Although the SS never endorsed Christian beliefs, the traditional rituals and practices of the Christian faith were generally tolerated and respected.[81] According to Bastian Hein, two reasons contributed to Himmler's Ersatz religion never catching on: On the one hand, Himmler himself was in a constant search for religious certainty, leaving his doctrine vague and unclear. On the other hand, Hitler personally intervened after the churches lamented the "neo-heathenish" tendencies within the SS, telling Himmler and Alfred Rosenberg to "cut out the cultic nonsense".[82]

Culture of violence

The SS was built on a culture of violence, which was exhibited in extreme form by the mass murder of civilians and prisoners on the Eastern Front.[83] In the summer of 1941 during Operation Barbarossa, participants in ideological training at the Fürstenberg SS school were sent out among the notorious Einsatzgruppen, where unit commanders were literally in competition to take the most violent and drastic measures against people deemed "enemies of the Reich."[84] Many of these officers, whether trained at the SS schools at Fürstenberg, Berlin-Charlottenburg, or elsewhere, occupied Einsatzgruppen posts in Lithuania, Poland, Ukraine, and the Soviet Union, as well as other security police and Gestapo offices throughout occupied-Europe, where they carried out atrocities and mass murder.[84] Training in the SS schools facilitated the necessary state of mind (Haltung) that rationalized violence—bolstered by stereotypes and prejudices—which was "reinforced by the preceding ideological manipulation."[85]

Historian Hans Buchheim wrote that the mentality and ideal values of the SS men were to be "hard," with no emotions such as love or kindness; hatred for the "inferior" and contempt for anyone who was not in the SS; unthinking obedience; "camaraderie" with fellow members of the SS; and an intense militarism that saw the SS as part of an "elite order" fighting for a better Germany.[86] The principal "enemy" of the SS, represented as a force of uncompromising, utter evil and depravity, was "world Jewry".[87] Members of the SS were encouraged to fight against the "Jewish-Bolshevik revolution of subhumans".[88]

The SS value of "fighting for fighting's sake" could be traced back to the values of the front-line German soldiers in World War I and the post-war Freikorps, and in turn led SS members to see violence as the highest possible value, and conventional morality as a hindrance to achieving victory.[89] The SS mentality fostered violence and "hardness".[90] The ideal SS man was supposed to be in a state of permanent readiness. As historian Hans Buchheim quips, "the SS man had to be forever on duty."[91] For members of the SS their mentality was such that for them, nothing was impossible no matter how arduous or cruel, to include the "murder of millions".[92] SS men who attempted to live by that principle of violence had an unusually high suicide rate.[93] The "soldierly" values of the SS were specific to the German post-World War I concept of the "political soldier" who was indoctrinated to be a "fighter" who would devote his life to struggling for the nation.[94]

Although not an SS document, the 1930 book Krieg und Krieger ("War and Warriors"), edited by Ernst Jünger, with contributions by Friedrich Georg Jünger, Friedrich Hielscher, Werner Best and Ernst von Salomon, served as an excellent introduction to the intellectual traditions from which the SS ideal arose.[91] The essays in Krieg und Krieger called for a revolutionary reorganization of German society, which was to be led by "heroic" leaders who would create a "new moral code" based upon the idea that life was a never-ending, Social Darwinian "struggle" that could only be settled with violence.[95] The book claimed that Germany had only been defeated in the First World War because the country had been insufficiently "spiritually mobilized", and what was required to win the next war was the proper sort of "heroic" leaders, unhindered by conventional morality, who would do what was necessary to win.[96] The values of the "heroic realism" literature gloried the principle and practice of fighting to the death regardless of the military situation.[97]

Out of the intellectual heritage of the "heroic realism" literature came a rejection of the traditional values of Christianity and the enlightenment (principles which were considered too sentimental); what emerged in its place was a cold indifference to the value of human life.[98] Marriage of the image of the "fighter" from "heroic realism" literature and the practical need of the SS to serve as political cadres for the National Socialist state, led to the elevation of the concept of "duty" as the highest obligation of the SS man.[99] The SS ethos called for "achievement for achievement's sake", where achievement ranked as the highest measurement of success.[100] As such, winning at all costs regardless the sacrifice became a supreme SS virtue.[101] The SS principle of loyalty above all, as reflected in the official slogan "My honour is loyalty", was severed from traditional moral considerations and instead focused entirely upon Hitler.[102] The idealized and distorted version of German history, which the organisation espoused, was intended to instill pride in members of the SS.[103] Himmler admonished the SS against pity, neighborly love, and humility, instead celebrating hardness and self-discipline.[104][105] Indoctrinating the SS to perceive racial "others" and state enemies as undeserving of their pity, helped create an environment and a mental framework where the men saw acts of wanton violence against those same enemies, not as a crime, but part of their patriotic obligation to the Nazi state.[106]

Ideology of genocide

As historian Claudia Koonz points out, "the cerebral racism of the SS provided the mental armor for mass murderers."[107] When Himmler visited Minsk and witnessed a mass killing of 100 people, he made a speech to the executioners emphasizing the need to put orders over conscience, saying that "soldiers ... had to carry out every order unconditionally".[108] According to historian George Stein, unquestioning obedience and "submission to authority" on the part of the SS represented one of the ideological "foundation stones" to combat the party's enemies.[109] As the Waffen-SS took part in the invasions of eastern European countries and the Soviet Union, the men wrote of their "great service in saving western civilization from being overrun by Asiatic Communism."[110]

One Waffen-SS recruiting pamphlet told potential members that answering the call meant being "especially bound to the National Socialist ideology," a doctrine which implied both an ideological battle and a racial struggle against subhumans (Untermenschen) accompanied by an unprecedented brutalization of warfare.[111] Participation in the "repellent task" of becoming psychologically involved in the killings was a rite of initiation of sorts and showed just how "internalized" the Nazi beliefs were for members of the SS. It was also part of the rhetoric of legitimation that gave meaning to their acts of extermination and habituated the SS to an ideology of genocide.[112]

Special SS death squads known as Einsatzgruppen were used for large-scale extermination and genocide of Jews, Roma and communists.[113][114] On 17 June 1941, Heydrich briefed the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen and their subordinate units on the general policy of killing Jews in the Soviet lands. SD member Walter Blume later testified that Heydrich called Eastern Jews the "reservoir of intellectuals for Bolshevism," and said that the "state leadership held the view that [they] must be destroyed."[115]

The SS Einsatzgruppen were supplemented by the specially created Order Police (drawn from Germany and/or the local populations) who were indoctrinated by the SS to also take part in mass killings.[116] Transforming members of the police organs of Germany into "instruments of genocide" was a marriage of "martial attitude" and "Nazi racial ideology," according to historian Edward B. Westermann.[117] To this end, Himmler and Kurt Daluege created an organizational culture across the entire SS and police complex that embodied militarization, obedience, and encompassed a specific worldview, actualizing the most extreme National Socialist ideals in the process.[118] Among these conceptions was the notion of the SS and the police as political soldiers with a higher calling against Bolshevism and Jews.[119]

One Order Police participant named Kurt Möbius testified during a postwar trial, that he believed the SS propaganda about the Jews being "criminals and sub-humans" who had caused "Germany's decline after the First World War." He went on to state that evading "the order to participate in the extermination of the Jews" never entered his mind.[120] One SS officer, Karl Kretschmer, "saw himself as a representative of a cultured people fighting a primitive, barbaric enemy," and wrote to his family of the need to desensitize himself from the mass killings.[121] Burleigh and Wippermann write: "Members of the SS administered, tortured, and murdered people with a cold, steely precision, and without moral scruples."[122]

_1b.jpg.webp)

The SS and its accompanying principles represented the realization of Nazi ideology and played a crucial role in the extermination of European Jews that followed the Nazis' rise to power. As historian Gerald Reitlinger states, while the idealism and machinery of the SS as a state within a state will all be forgotten, their acts of "...racial transplantations, the concentration camps, the interrogation cells of the Gestapo, the medical experiments of the living, the mass reprisals, the manhunts for slave labor and the racial exterminations will be remembered forever."[123]

Historian Hans Buchheim argues there was no coercion to murder Jews and others, and all who committed such actions did so out of free will.[124] He wrote that chances to avoid executing criminal orders "were both more numerous and more real than those concerned are generally prepared to admit".[125] Buchheim commented that until the middle of 1942, the SS had been a strictly volunteer organization, and that anyone who joined the SS after the Nazis had taken over the German government either knew or came to know that he was joining an organization that would be involved in atrocities of one sort or another.[126] There is no known record of an SS officer refusing to commit an atrocity; they willingly did so, and then cherished the awards they received for doing it.[127]

Initially the victims were killed with gas vans or firing squad by SS Einsatzgruppen units, but these methods proved impracticable for an operation of the scale carried out by the Nazi state.[128] In August 1941, SS leader Himmler attended the shooting of 100 Jews at Minsk. Nauseated and shaken by the experience,[129] he was concerned about the impact such actions would have on the mental health of his SS men. He decided that alternate methods of killing should be found.[130][131] On his orders, by spring 1942 the camp at Auschwitz had been greatly expanded, including the addition of gas chambers, where victims were killed using the pesticide Zyklon B.[132] Industrialized killing at the SS operated extermination camps made these Nazi-conceived institutions into places where the productive output was corpses.[133] By the end of the war, at least eleven million people, including 5.5 to 6 million Jews[1][134] and between 200,000 and 1,500,000 Romani people[135][134] had been killed by the Nazi state with assistance by collaborationist governments and recruits from occupied countries.[136][137] Historian Enzo Traverso asserts that massacring millions of people was part of the Nazi ideology comprising "total war," which constituted their attempt at conquest for both "racial" and colonial purposes.[138] Acting on Hitler's orders, Himmler was a main architect of the Holocaust[139][140] and the SS was the main branch of the Nazi Party that implemented it.[141]

Post-war

On 23 May 1945, Himmler, who had been responsible for so much of the SS doctrine and that of the Nazi state, committed suicide after he was captured by the Allies.[142] Other senior members of the SS fled.[143] Chief of the Reich Security Main Office, SS-Obergruppenführer Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who was the highest-ranking member of the SS upon Himmler's suicide, was captured in the Bavarian Alps and tried at the Nuremberg Tribunal along with other leading Nazis like Hermann Göring, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, among others. Kaltenbrunner was convicted of crimes against humanity and executed on 16 October 1946.[144]

Other SS intellectuals and physicians were also brought to trial and convicted, including the SS Ahnenerbe doctors who killed the enfeebled and/or disabled persons deemed "unworthy to live" or who performed medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners.[145] During questioning after the war, many of the SS doctors from the concentration camps avowed that the allegiance they had sworn to Hitler superseded any of the rituals performed at medical school, to say nothing of the Hippocratic Oath they had otherwise ignored.[146] SS members absolved themselves through the pseudo-scientific justification that they were merely acting as instruments (men of action) on behalf of the German people in pursuit of "racial hygiene."[147] Similar strategies of negation and dismissal of responsibility were displayed by SS men during their post-war trials, either by way of legitimizing their actions as a result of unconditional obedience to their superiors (intimating responsibility onto them) or through the use of innocuous-sounding bureaucratic language.[148]

Given the impact that the Nazi ideology had on the European continent in causing a catastrophic war and unparalleled crimes, the Allied powers demilitarized Germany and divided the country into four occupation zones.[149] They also began the process of denazification (Entnazifizierung). This was essentially an effort to "purge" the German people of the Nazi ideology that had pushed them to war and resulted in the Holocaust.[150] Many members of the SS, including some from the upper echelons, faced little more than a stint in a prisoner-of-war camp and a short denazification hearing. One writer has said that they were treated with "remarkable leniency".[151]

Notes

- ↑ The Nazis believed that homosexuality "defied the command structure of government and military institutions"[7]

- ↑ Himmler wrote a 1942 memo urging "ruthless severity" to eliminate the "dangerous and infectious plague," and the death penalty was instituted for homosexuality in the SS.[8]

- ↑ By the time World War II in Europe was underway, additional SS Leadership Schools at Klagenfurt, Posen-Treskau and Prague had been founded.[25]

- ↑ General military instruction over logistics and planning was also provided but much of the training concentrated on small-unit tactics associated with raids, patrols, and ambushes.[26] Training an SS officer took as much as nineteen months overall and encompassed additional things like map reading, tactics, military maneuvers, political education, weapons training, physical education, combat engineering and even automobile mechanics, all of which were provided in varying degrees at additional training facilities based on the cadet’s specialization.[27]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Evans 2008, p. 318.

- ↑ Ingrao 2013, pp. 52–61.

- 1 2 Frøland 2020, p. 190.

- ↑ Frøland 2020, pp. 190–191.

- 1 2 3 4 Frøland 2020, p. 191.

- ↑ Birn 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ Boden 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Giles 2002, p. 269.

- ↑ Browder 1996, p. 275.

- ↑ Mineau 2014, pp. 307–309.

- ↑ Matthäus 2006, pp. 117–118.

- 1 2 Matthäus 2006, pp. 118.

- ↑ Mineau 2011, p. 23.

- ↑ Mineau 2011, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, p. 191.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 191.

- ↑ Spielvogel 1992, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Koonz 2005, p. 238.

- ↑ Webman 2012, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Bialas 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ Frei 1993, p. 88, 119.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 44.

- ↑ Hein 2015, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Weale 2012, p. 206.

- ↑ Pine 2010, p. 89.

- ↑ Weale 2012, p. 207.

- ↑ Weale 2012, pp. 207–208.

- ↑ Hartmann 1972, pp. 143–147.

- ↑ Banach 1998, pp. 98–100.

- ↑ Bracher 1970, pp. 350–362.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 39.

- ↑ Nolzen 2009, p. 35.

- ↑ Hein 2015, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 35.

- ↑ Ziegler 1989, pp. 52–53, 113, 135.

- ↑ Wegner 1985, pp. 430–434.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Ziegler 1989, p. 127.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 37.

- ↑ Koehl 2004, pp. 59, 62.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, p. 192.

- ↑ Longerich 2012, p. 352.

- 1 2 3 Longerich 2012, p. 123.

- ↑ Trevor-Roper 2008, p. 83.

- ↑ Longerich 2012, pp. 353–358.

- ↑ Ingrao 2013, p. 51–63.

- ↑ Proctor 1988, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Proctor 1988, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Hein 2015, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Carney 2013, p. 60.

- ↑ Carney 2013, pp. 74, 77.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 57.

- ↑ Hein 2015, pp. 55–58.

- ↑ Birn 2009, pp. 65–73.

- ↑ Gingerich 1997, p. 815.

- 1 2 3 Longerich 2012, p. 265.

- ↑ Longerich 2012, p. 270.

- ↑ Evans 2005, pp. 234–239.

- 1 2 Höhne 2001, p. 135.

- ↑ Lapomarda 1989, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 Höhne 2001, p. 146.

- ↑ Steigmann-Gall 2003, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 47.

- ↑ Höhne 2001, pp. 138, 143, 156.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 50.

- ↑ Gerwarth 2011, p. 102.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, pp. 303, 396.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 195.

- ↑ Gerwarth 2011, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Höhne 2001, p. 200.

- ↑ Gerwarth 2011, p. 105.

- ↑ Steigmann-Gall 2003, p. 133.

- ↑ Burleigh & Wippermann 1991, p. 273.

- ↑ Schulte 2009, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 52.

- ↑ Schulte 2009, p. 9.

- ↑ Hein 2015, p. 51.

- ↑ Flaherty 2004, pp. 38–49.

- ↑ Höhne 2001, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Frei 1993, p. 85.

- ↑ Steigmann-Gall 2003, pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Hein 2015, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Fritz 2011, pp. 69–70, 94–108.

- 1 2 Matthäus 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ Matthäus 2006, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, pp. 320–321.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 321.

- ↑ Himmler 1936, p. 8.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, pp. 323–327.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 320.

- 1 2 Buchheim 1968, p. 323.

- ↑ Frei 1993, p. 107.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, p. 193.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, pp. 321–323.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 324.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 325.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, pp. 191–195.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, pp. 326–327.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 328.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, pp. 193–195.

- ↑ Burleigh 2000, p. 195.

- ↑ Höhne 2001, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Koonz 2005, p. 246.

- ↑ Schroer 2012, p. 35.

- ↑ Bialas 2013, pp. 358–359.

- ↑ Koonz 2005, p. 250.

- ↑ Hilberg 1961, pp. 218–219.

- ↑ Stein 1984, p. 123.

- ↑ Stein 1984, p. 124.

- ↑ Stein 1984, pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Ingrao 2013, pp. 205–208.

- ↑ Rhodes 2003, p. 14.

- ↑ Breitman 1990, pp. 341–342.

- ↑ Breitman 1991, pp. 434–435.

- ↑ Rhodes 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Westermann 2006, p. 129.

- ↑ Westermann 2006, pp. 129–131.

- ↑ Westermann 2006, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Rhodes 2003, p. 159.

- ↑ Schroer 2012, p. 38.

- ↑ Burleigh & Wippermann 1991, p. 274.

- ↑ Reitlinger 1989, p. 454.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, pp. 372–373.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 373.

- ↑ Buchheim 1968, p. 390.

- ↑ Blood 2006, p. 16.

- ↑ Evans 2008, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Gilbert 1987, p. 191.

- ↑ Longerich 2012, p. 547.

- ↑ Gerwarth 2011, p. 199.

- ↑ Evans 2008, pp. 295, 299–300.

- ↑ Traverso 2003, pp. 38–39.

- 1 2 Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ↑ Hancock 2004, pp. 383–396.

- ↑ Rummel 1994, p. 112.

- ↑ Snyder 2010, p. 416.

- ↑ Traverso 2003, p. 75.

- ↑ Shirer 1960, p. 236.

- ↑ Longerich 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Longerich 2000, p. 14.

- ↑ Evans 2008, p. 729.

- ↑ Weale 2012, p. 410.

- ↑ Wistrich 2001, p. 136.

- ↑ Pringle 2006, pp. 295–296.

- ↑ Lifton 1986, p. 207.

- ↑ Ingrao 2013, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ Ingrao 2013, pp. 228–248.

- ↑ Bessel 2010, pp. 169–210.

- ↑ MacDonogh 2009, pp. 348–362.

- ↑ Höhne 2001, p. 581.

Bibliography

- Banach, Jens (1998). Heydrichs Elite: Das Fuhrerkorps der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD 1936–1945 (in German). Paderborn: F. Schöningh. ISBN 978-3-506-77506-1.

- Bessel, Richard (2010). Germany 1945: From War to Peace. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-054037-1.

- Bialas, Wolfgang (2013). "The Eternal Voice of the Blood: Racial Science and Nazi Ethics". In Anton Weiss-Wendt; Rory Yeomans (eds.). Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938–1945. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4605-8.

- Bialas, Wolfgang (2014). "Nazi Ethics and Morality: Ideas, Problems and Unanswered Questions". In Wolfgang Bialas; Lothar Fritze (eds.). Nazi Ideology and Ethics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-44385-422-1.

- Birn, Ruth Bettina (2009), "Die SS - Ideologie und Herrschaftsausübung. Zur Frage der Inkorporierung von "Fremdvölkischen"", in Schulte, Jan Erik (ed.), Die SS, Himmler und die Wewelsburg (in German), Paderborn, pp. 60–75, ISBN 978-3-506-76374-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Blood, Philip (2006). Hitler's Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Nazi Occupation of Europe. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-021-1.

- Boden, Eliot H. (2011). "The Enemy Within: Homosexuality in the Third Reich, 1933–1945". Constructing the Past. 12 (1).

- Bracher, Karl-Dietrich (1970). The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism. New York: Praeger Publishers. ASIN B001JZ4T16.

- Breitman, Richard (1991). "Himmler and the 'Terrible Secret' among the Executioners". Journal of Contemporary History. 26 (3/4): 431–451. doi:10.1177/002200949102600305. JSTOR 260654. S2CID 159733077.

- Breitman, Richard (1990). "Hitler and Genghis Khan". Journal of Contemporary History. 25 (2/3): 337–351. doi:10.1177/002200949002500209. JSTOR 260736. S2CID 159541260.

- Browder, George C (1996). Hitler's Enforcers: The Gestapo and the SS Security Service in the Nazi Revolution. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510479-0.

- Buchheim, Hans (1968). "Command and Compliance". In Krausnik, Helmut; Buchheim, Hans; Broszat, Martin; Jacobsen, Hans-Adolf (eds.). Anatomy of the SS State. New York: Walker and Company. ISBN 978-0-00211-026-6.

- Burleigh, Michael (2000). The Third Reich: A New History. Hill & Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-9326-7.

- Burleigh, Michael; Wippermann, Wolfgang (1991). The Racial State: Germany 1933–1945. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39802-2.

- Carney, Amy (2013). "Preserving the 'Master Race': SS Reproductive and Family Policies during the Second World War". In Anton Weiss-Wendt; Rory Yeomans (eds.). Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938–1945. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4605-8.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

- Flaherty, T. H. (2004) [1988]. The Third Reich: The SS. Time-Life. ISBN 1-84447-073-3.

- Frei, Norbert (1993). National Socialist Rule in Germany: The Führer State, 1933–1945. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18507-0.

- Fritz, Stephen G (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-81313-416-1.

- Frøland, Carl Müller (2020). Understanding Nazi Ideology: The Genesis and Impact of a Political Faith. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc. ISBN 978-1-4766-7830-6.

- Gerwarth, Robert (2011). Hitler's Hangman: The Life of Heydrich. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11575-8.

- Gilbert, Martin (1987) [1985]. The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. New York: Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-0348-2.

- Giles, Geoffrey J (January 2002). "The Denial of Homosexuality: Same-Sex Incidents in Himmler's SS and Police". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 11 (1/2): 256–290. doi:10.1353/sex.2002.0003. S2CID 142816037.

- Gingerich, Mark P. (1997). "Waffen SS Recruitment in the 'Germanic Lands,' 1940–1941". Historian. 59 (4): 815–831. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1997.tb01377.x. JSTOR 24451818.

- Hancock, Ian (2004). "Romanies and the Holocaust: A Reevaluation and an Overview". In Stone, Dan (ed.). The Historiography of the Holocaust. New York; Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-99745-1.

- Hartmann, Peter (1972). "Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Wilhelm-Pieck-Universität Rostock – Gesellschafts und Sprachwissenschaftliche Reihe". Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Wilhelm-Pieck-Universität Rostock. Gesellschaftswissenschaftliche Reihe (in German). Rostock Verlag. ISSN 0323-4630.

- Hein, Bastian (2015). Die SS. Geschichte und Verbrechen (in German). Munich: C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-67513-3.

- Hilberg, Raul (1961). The Destruction of the European Jews. Chicago: Quadrangle Books.

- Himmler, Heinrich (1936). Die Schutzstaffel als Antibolschewistische Kampforganisation (in German). Franz Eher Verlag.

- Höhne, Heinz (2001). The Order of the Death's Head: The Story of Hitler's SS. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-139012-3.

- Ingrao, Christian (2013). Believe and Destroy: Intellectuals in the SS War Machine. Malden, MA: Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-6026-4.

- Kitchen, Martin (1995). Nazi Germany at War. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-07387-1.

- Koehl, Robert L. (2004). The SS: A History, 1919–45. Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2559-7.

- Koonz, Claudia (2005). The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01842-6.

- Lapomarda, Vincent (1989). The Jesuits and the Third Reich. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-88946-828-3.

- Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-46504-905-9.

- Longerich, Peter (2000). "The Wannsee Conference in the Development of the 'Final Solution'" (PDF). Holocaust Educational Trust Research Papers. London: The Holocaust Educational Trust. 1 (2). ISBN 0-9516166-5-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02.

- Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6.

- MacDonogh, Giles (2009). After the Reich: The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00337-2.

- Matthäus, Jürgen (2006). "Anti-Semitism as an Offer: The Function of Ideological Indoctrination in the SS and Police Corps During the Holocaust". In Dagmar Herzog (ed.). Lessons and Legacies VII: The Holocaust in International Perspective. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-2370-3.

- Mineau, André (2011). SS Thinking and the Holocaust. New York: Editions Rodopi. ISBN 978-94-012-0782-9.

- Mineau, André (2014). "SS Ethics within Moral Philosophy". In Wolfgang Bialas; Lothar Fritze (eds.). Nazi Ideology and Ethics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-44385-422-1.

- Nolzen, Armin (2009), ""... eine Art von Freimaurerei in der Partei"? Die SS als Gliederung der NSDAP, 1933–1945", in Schulte, Jan Erik (ed.), Die SS, Himmler und die Wewelsburg (in German), Paderborn, pp. 23–44, ISBN 978-3-506-76374-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pine, Lisa (2010). Education in Nazi Germany. New York: Berg. ISBN 978-1-84520-265-1.

- Pringle, Heather (2006). The Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-714812-7.

- Proctor, Robert (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-74578-0.

- Reitlinger, Gerald (1989). The SS: Alibi of a Nation, 1922–1945. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80351-2.

- Rhodes, Richard (2003). Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-375-70822-0.

- Rummel, Rudolph (1994). Death by Government. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. ISBN 978-1-56000-145-4.

- Schroer, Timothy L. (February 2012). "Civilization, Barbarism, and the Ethos of Self-Control among the Perpetrators" (PDF). German Studies Review. 35 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1353/gsr.2012.a465656. S2CID 142106304.

- Schulte, Jan Erik (2009), "Himmlers Wewelsburg und der Rassenkrieg. Eine historische Ortsbestimmung", in Schulte, Jan Erik (ed.), Die SS, Himmler und die Wewelsburg (in German), Paderborn, pp. 3–20, ISBN 978-3-506-76374-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

- Spielvogel, Jackson (1992). Hitler and Nazi Germany: A History. New York: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-393182-2.

- Steigmann-Gall, Richard (2003). The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945. New York and London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82371-5.

- Stein, George H. (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–1945. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9275-4.

- Traverso, Enzo (2003). The Origins of Nazi Violence. New York and London: The New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584788-0.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh, ed. (2008). Hitler's Table Talk, 1941–1944: His Private Conversations. New York: Enigma. ISBN 978-1-61523-824-8.

- Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York: Caliber Printing. ISBN 978-0-451-23791-0.

- Webman, Esther (2012). The Global Impact of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion: A Century-Old Myth. Routledge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-136-70609-7.

- Wegner, Bernd (1985). "The Aristocracy of National Socialism: The Role of the SS in National Socialist Germany". In H.W. Koch (ed.). Aspects of the Third Reich. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-33335-273-1.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton; Yeomans, Rory, eds. (2013). Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938–1945. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4507-5.

- Westermann, Edward B. (2006). "Ideology and Organizational Culture: Creating the Police Soldier". In Dagmar Herzog (ed.). Lessons and Legacies VII: The Holocaust in International Perspective. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-2370-3.

- Wistrich, Robert (2001). Who's Who In Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-11888-0.

- Ziegler, Herbert F. (1989). Nazi Germany's New Aristocracy: The SS Leadership, 1925–1939. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05577-7.

Online

- "Introduction to the Holocaust". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

Further reading

- Allen, Michael Thad (2002). The Business of Genocide: The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps. London and Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80782-677-5.

- Bessel, Richard (2006). Nazism and War. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-81297-557-4.

- Bloxham, Donald (2009). The Final Solution: A Genocide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19955-034-0.

- Breitman, Richard (1991b). The Architect of Genocide: Himmler and the Final Solution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-39456-841-6.

- Diner, Dan (2006). Beyond the Conceivable: Studies on Germany, Nazism, and the Holocaust. Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52021-345-6.

- Ehrenreich, Eric (2007). The Nazi Ancestral Proof: Genealogy, Racial Science, and the Final Solution. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-25334-945-3.

- Friedlander, Henry (1997). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4675-9.

- Friedländer, Saul (2009). Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933–1945. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06135-027-6.

- Hale, Christopher (2011). Hitler's Foreign Executioners: Europe's Dirty Secret. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-75245-974-5.

- Hilberg, Raul (1992). Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe, 1933–1945. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-8419-0910-5.

- Hutton, Christopher (2005). Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Dialectic of Volk. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-74563-177-6.

- Kershaw, Ian (2000). Hitler: 1889-1936, Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39332-035-0.

- Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler: 1936-1945, Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39332-252-1.

- Kogon, Eugen (2006). The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System behind Them. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-37452-992-5.

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. New York; Toronto: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59420-188-2.

- Müller, Rolf-Dieter (2012). The Unknown Eastern Front: The Wehrmacht and Hitler's Foreign Soldiers. New York: I.B. Taurus. ISBN 978-1-78076-072-8.

- Rabinbach, Anson; Gilman, Sander L., eds. (2013). The Third Reich Sourcebook. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52020-867-4.

- Rempel, Gerhard (1989). Hitler's Children: The Hitler Youth and the SS. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4299-7.

- Schafft, Gretchen E (2004). From Racism to Genocide: Anthropology in the Third Reich. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-25207-453-0.

- Sereny, Gitta (1974). Into That Darkness: From Mercy Killings to Mass Murder. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-394-71035-5.

- Sofsky, Wolfgang (1997). The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69100-685-7.

- Sydnor, Charles (1977). Soldiers of Destruction: The SS Death's Head Division, 1933–1945. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ASIN B001Y18PZ6.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2007). Nazi Ideology and the Holocaust. Washington DC: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0-89604-712-9.

- Weikart, Richard (2006). From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-40396-502-8.