This article collects the History of Nairn, Nairn (/ˈnɛərn/ NAIRN; Scottish Gaelic: Inbhir Narann) is a town and Royal burgh in the Highland council area of Scotland. It is an ancient fishing port and market town around 17 miles (27 km) east of Inverness. It is the traditional county town of Nairnshire.

Pre-history

Human settlement in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Scotland is known to have been established around 10,000 years ago and such communities are likely to have been present in the fertile lands and fishing areas of Nairn at this time. In the Mesolithic era easy access to flint provided tools. Retouched flint flakes, tardenoisian-type microlithic forms have been found within the Culbin Sands indicating close by communities in this age around 8,000 – 5,000 BC.

During the Neolithic period from 4,000 BC – 2,500 BC humans were developing water craft capable of deeper sea voyages and again the mouth of the river where Nairn now sits would have been a regular travel point and easy shelter. Nearby mixed-forests would provide wolf, wild boar and red deer meat and resources for tooling and clothing.[1]

Neolithic to Late Bronze Age artefacts. Stone axes, flint arrowheads, saws and scrapers have been discovered south of Nairn in the Slagachorrie or (Scottish Gaelic: lag a' choire) "Hollow of the Corrie" area. Known locally as "The Flint Pit" just two miles south of Nairn. Many of the archaeological finds noted here are held in Nairn Museum. These discoveries indicate a hunter's settlement with items designed for the preparation of animals. As well as this two significant circular stone-walled huts believed to also date from the Bronze Age among over thirty others. With these sites within fifteen miles of Nairn it is believed Nairn may have also contained sites which were built over in later centuries.[2][3]

1AD to 12th Century

The Picts

Relics of religious Pictish worship in the form of stone circles can be seen in Nairnshire. In Moyness (Scottish Gaelic: Maigheanas), Auldearn, Urchany (Scottish Gaelic: Urchanaidh), Ballinrait (Scottish Gaelic: Baile an Ratha), Dalcross, Croy (Scottish Gaelic: Croidh), Daviot (Scottish Gaelic: Deimhidh) and in the Viewfield area of the town of Nairn itself.[4] In later years many of these areas became linked with local superstitions, laws and ritual. The Moyness Standing Stone contained a logan, or rocking stone. Used to determine the guilt of someone accused of crime. Should the stone move when they are placed upon it the person was found to be guilty. Dundeasil near Clunas (Scottish Gaelic: Cluaineas) had the local custom of walking in circles around it thrice before starting a work day for good luck. It is likely some of the elements found within Nairn town held the same superstitions.[5]

In 86 AD Agriocola dispatched a Roman fleet from the Firth of Forth to explore the island, the fleets sailors relayed this information to the Geographer Ptolemy. On his Strasburg Edition a river named Loxa can be seen to be located in Nairn or Lossiemouth. Evidence of local settlements along the coast are noted though none specifically can be identified as Nairn.[6] In the Delnies area of Nairn a rounded earthwork Roman Camp was discovered indicating some habitation, possibly temporary during this time period but very little remains of this site today.[7][5]: 298–309 This is supported by urns containing silver roman coins from the same era being discovered within the town of Nairn though the exact location of this discovery is unknown similar coins were found in nearby Auldearn.[8]

"Some years ago was dug up in a common near Nairn an urn containing a series of roman silver coins of different emperors ... At Inshoch in the parish of Auldearn about three miles east of Nairn, there were found in a moss several remains of Roman coins, two heads of a Roman hasta or spear, two heads of the roman horseman's spear ... and a round piece of thin metal hollow on the underside, all of ancient Roman brass."

— Gough, Richard, Anecdotes of British Topography (1780)

Ekkailsbakki

The true origin and founding of the town of Nairn is unknown, it is believed from the Narmin of Boece that it was here that Sigurd, Earl of Orkney built his burg in the latter part of the 9th century named Ekkailsbakki at the mouth of the Findhorn river when its mouth was where the Old Bar area of Nairn is now located. This is located within what was the Culbin estate, a name of Danish origin. Sigurd, Earl of Orkney took control of the area known as Moray inclusive of Nairn.[9][5]: 56-58 There is also recorded evidence of a castle being in existence in Nairn in the 11th century when it was attacked by Danes alongside those castles of Forres and Elgin who defeated the Royal Army of Malcolm II.[10]

St. Ninian

The existence of St. Ninian on the seal of Nairn shows a connection to the figure, however three people are identified as potentially being or having all been St Ninian: Saint Finnian of Moville, Saint Finnian of Clonard, and Saint Finbarr of Cork.[11] The earliest mention of this figure is in AD 731 in The Ecclesiastical History of the English People but he is believed to have died by AD 432. It is unclear if a figure known as St. Ninian visited Nairn or if the figure was brought to worship by an outside force. The first account of Christianity in Nairn is brought by St. Columba where in 563, he travelled to Scotland. He visited the pagan King Bridei in 565 who controlled the area containing Nairn at the time from his fort in Inverness. He was unable to convert the king but did become a trusted and respected person of the king. It was at this time he travelled as a missionary throughout the Highlands and to Nairn to preach Christianity.[12] A chapel discovered in the Lochloy area of Nairn is believed to have been from this era but no records remain of which Saint it was dedicated to.[5]: 36

The early Kings of Alba

_-_Duncan_I%252C_King_of_Scotland_(1034-40)_-_RCIN_403308_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

Nairn was likely under control of the Mormaer of Moray given its continued ownership in future years under the title Earl of Moray. From Findláech of Moray in 1014 through to Macbeth when he died in 1057. From 1034 to 1040 Duncan I of Scotland was King of Alba and basis of the "King Duncan" in Shakespeare's play Macbeth. When Duncan died on 14 August 1040 he was buried in Elgin when trying to attack Moray and so it is believed Macbeth would at this time have had control over the area of modern Nairnshire as far as the town of Nairn if not also Forres and Elgin. Macbeth becoming king after the death of Duncan in 1040.[13][14]

Macbeth was succeeded by Malcolm III of Scotland 1058 and it is in 1060 we see the first Baron of Cawdor, Hugh de Cadella. Hugh is noted to have served Malcolm III and was granted the title of Baron. Malcolm III had taken over the lands of Macbeth furthering the evidence this title was held by the Mormaer of Moray historically. The Barons, later to become Thanes of Cawdor would go on to hold titles of Sheriff of Nairn several times throughout history and much of the land of modern-day Nairn.[15][16]

12th Century

The Baron of Cawdor

In 1104 Scotland King Edgar granted the lands of Cawdor to Gilbertus de Cadella, the son of Hugh and second Baron of Cawdor. This title had passed to Alexander de Cadella, son of Gilbertus by 1112. Alexander having assisted King Alexander I prevent his assassination by clans Macdonald, Murray and Cummings. Both appointments including control over the lands of Nairn[16]

Nairn was included traditionally within the diocese of Moray believed to be formed in the reign of Alexander I around 1122 which extended to Spey to the River Beauly. The existence of a later writ evidences at this time much of the land of Nairn and where Nairn castle would be sited had previously belonged to the church or to the Bishop of Moray himself.[5]: 119 Gregoir of Moray is recorded however as the first Bishop of Moray, inclusive of Nairn in 1114.[17]

Royal Burgh of Nairn

David I of Scotland (Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim) took possession of Celtic Moray including Nairn and as far north as Inverness 1130 from Óengus of Moray.[18] He encouraged settled industry and feudal ruling ideals in nearby towns and the city of Inverness. Inverness became a hub of ship building while the surrounding towns like Nairn, Forres and Elgin were fishing ports focused on herring using the produced ships of Inverness. At this time the Earldom of Moray, the hereditary rules of Moray was removed as a title.[5]: 77

The existence of Nairn as a Royal Burgh is evidenced to date from the time of David I. James VI submitted a charter of confirmation, approved by act of parliament in 1597 which refers to a charter of Alexander II, when the king granted land to the Bishop of Moray. This was in turn a continuation of a charter by William the Lion, which was confirming rights granted by David I. The existence of the original documents by David I of Scotland, William the Lion and Alexander II no longer exist in physical form and are only referenced.[19][4]: 281

MacHeths insurrection

Wymund who took the name Malcolm MacHeth, the son of Óengus of Moray, the former King of Moray, while supported by the King of Norway attempted to raise an insurrection against David I with men from Inverness, Forres, Elgin and Nairn. This insurrection failed and MacHeths was captured, confined in Roxburgh.[20] In 1153 Malcolm IV, son of David I was crowned and took control of the Moray area. Men in Nairn were taken from their homes and redistributed to other areas of Malcolm's kingdom to reduce the growing dissent of the area. An introduction of English speaking Knights and Squires in significant lands as employers and merchants with the native speaking Scottish Gaelic residents served to encourage the growth of English to the more dominant language in Nairn and the surrounding areas as it is in the modern day. This was furthered by the installation of English speaking Christian churches in the town.[5]: 75–82

"He removed them all from the land of their birth, and scattered them throughout the other districts of Scotland both beyond the hills and on this side thereof, so that not even a native of that land abode there, and he installed his own peaceful people."

William the Lion

In 1165 control of Nairn came to William the Lion which he exerted control over from nearby Inverness from 1179 and was known to visit Nairn regularly staying at Nairn Castle. The castle of Nairn stood in what was known as Constabulary Garden near the High Street to the south of this exists in modern-day Nairn Castle Lane and Castle Square. To the bottom of Castle Lane near the River Nairn remains of what is believed to be the steps for loading goods to the castle from the river. One side of this castle was protected by the River Nairn and the north and west sides were protected by ramparts and ditches, the entrance being by a drawbridge. The castle ground extended as far as the present Bridge Street, and was enclosed by a stout palisade and earthwork.[22][23] William the Lion created the first governor and sheriff of Nairn and its castle by naming Baron William Pratt as such where a regular garrison of royal troops would be based. The Burgess was named as Andrew Cumming. Both Pratt and Cumming being names of English origin there are believed to have been English nobles or lowland Scots.

A writ in the time of William the Lion shows the Bishop of Nairn had given possession of lands in Nairn to King William for the expansion of Nairn Castle. Implying much of the land of Nairn and the castle had previously belonged to the church or to the Bishop of Moray himself. Possession of Auldearn was provided in compensation.[5]: 119

It was in Nairn in the autumn of 1196 that William the Lion was to receive "all his enemies" from Harold MacMadit who had previously occupied Caithness and whose son had sought to revolt against the king. Harold allowed those prisoners to escape in the Lochloy area of Nairn including his son Thorfinn. Allowing them to escape as this was his only heir. William left Nairn bringing Harold to Edinburgh castle to wait his son being traded as hostage.[24][5]: 88

13th Century

Edward I, Lord Paramount

In 1207 we see the first recorded Dean of Moray, head of the Diocese of Moray by the name of Freskin with Bricius de Douglas and Andreas de Moravia as bishops below him.[25] Alexander II, William's son became ruler of Nairn after 1214 and shortly after men from the surrounding garrisons and Nairn were needed to put down a revolution of the MacHeths former holders of the title King of Moray but King Alexander II is not known to have visited Nairn with significance during his rule. His son King Alexander III likewise in his rule of Nairn from 6 July 1249 – 19 March 1286 is not known to visit.[26]

During his reign the sheriffs of Nairn were keepers of Nairn Castle. In 1264 Alexander de Moravia, the then sheriff, was repaid by the royal treasurer for expense incurred in plastering the hall, in placing locks on the doors of the keep, and in providing two cables for the drawbridge. This repayment shows a control from the king and expectation of payment for care, but day-to-day running being handled by the sheriff.[19][5]: 84

As Margaret, daughter of Alexander III, was three years old at the time of his death all areas north of the River Forth were governed from 1286 by Alexander Comyn, Earl of Buchan and Donnchadh III, Earl of Fife but after their deaths in 1288 it is unknown who took this role. The servants of Edward I stopped in Nairn on the 27th of September 1290 where they left their horses en route to secure Margaret to marry Edward II of England but Margaret had died on the journey from Norway. The same agents of Edward I returned through Nairn on 10 October where they remained for three days.[27][5]: 95-100

Rival noble factions formed in Scotland following the death of Margaret. The men of Moray at this time appealed to Edward I for assistance stating they felt William Fraser, Bishop of St Andrews and John Comyn II of Badenoch had usurped control of Moray (at this time still including Nairn). They were stated to have "destroyed and plundered" towns, "burned barns full of corn" in Nairn and killed women and children. William Fraser and John Omyn were in favour of the passing of the crown of Scotland to John Balliol while those from Moray who drafted the appeal were in favour of Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale. This letter among others provided pretext to Edward I to become involved in the disputed crown. Edward I became Lord Paramount of Scotland on the 11th of June. Taking control of the government of the country and all royal fortresses including that of Nairn which became garrisoned with English troops. Daily running of the castle of Nairn was conducted by William de Braytoft an English knight.[28] [5]: 100-102

"To all .who may see or hear of these presents, I, Thomas de Braytoft, Keeper of the Castles of Nairn and Cromarty, on behalf of the illustrious King, Lord Edward, by the grace of God, King of England, constituted Overlord of the Realm of Scotland, greeting Know all men that I, on Thursday preceding the Feast of Pope St. Gregory, in the year of our Lord 1292, received by the hands of Sir Gervaise de Raite, Knight, constable of Nairn, as the dues and arrears of the bailieship of Invernairn, for my service and custody of the Castles of Nairn and Cromarty, £11 sterling. In witness whereof I have granted these presents to Sir Gervaise -Given at Raite, day and year foresaid."

Edward I named John Balliol King of Scots and on the 18th November 1292 on receiving a letter from Edward William de Braytoft raised the colours of John Balliol above the Castle of Nairn.[5]: 105 Edward I continued to act as Lord Paramount of Scotland following John Balliol's coronation. Edward I ordering a gift to the Bishop of Glasgow be paid by Reginald le Chen, sheriff of Nairn from the arrears of Nairn's county crown revenue a sum of £500.[30]

First War of Scottish Independence

The first named Thane of Cawdor (formerly Baron), Donald Calder was recorded present in Nairn Parish Church attending the valuation of the Lands of Kilravock and Easter Geddes in August 1295. Control of Nairn town had been traditionally within the Barony that became the Thanedom.[16][15]

Following a summoning of John Balliol to the English Parliament to answer charges by Macduff, son of Malcolm II, Earl of Fife[31] and demand from Edward I that Scotland provide forces to fight his war with France.[32] The Scottish nobles formed an alliance with France on 23 October 1295 and attacked the city of Carlisle placing Nairn in a war between Scotland, France and England.[33] Following Edward I bringing a large army to Scotland, it was in Aberdeen that the Castle of Nairn was surrendered to him in June 1296 by Sir Gervase de Rathe, Constable of Invernairn and on the 25th of July Edward's army entered Moray.

Sir Reginald Chien, Sheriff of Nairn, was deceased and so his duties were signed to his wife. Shortly after troops were stationed in Nairn as a garrison to ensure the swearing of allegiance. Edward I signed the writs summoning all the prominent Scottish landowners, churchmen and burgesses on 28 August 1296 in nearby Elgin before returning south four days later. At this time he also ordered lands of Walter Herok, Dean of Moray to have his lands returned as they had previously been taken in the previous year.[4]: 6 [5]: 122 Sir Gervase de Rathe, Sir Andrew de Rathe and Alan de Moravia attended the summoning of the Scottish Parliament in Berwick by Edward I representing Nairn. Henry de Rye who had previously attended Nairn en route to collect Margaret was given governing control over everything north of the River Forth and as such Nairn. Henry de Rye forfeited any noble Scottish lands that had been seen to be unfriendly to the English king. Resistant Nairn residents were faced with severe taxes, heavy fines or imprisonment.[5]: 104-110 The Knights Templar at this time were also provided lands within Nairn formerly possessed by John Rose and Hew Rose as were Knights Hospitaller.[5]: 133-134 [4]: 6

In 1297 Sir Andrew Moray raised a small army at Avoch Castle north of Inverness to fight against Edward I and his occupation of Scotland. He appealed to those of Nairn who had first appealed to Edward I to redeem their character. The Royal Castles of Forres, Elgin and Nairn were assaulted as were residences of those who held offices of governance. The English Sheriff of Aberdeen, Sir Henry de Latham, was ordered on 11 June 1297 to deal with rebels in the north-east and an army was dispatched to Moray on July 1297. Passing through Nairn, the Sir Andrew Moray met the army of Sir Henry de Latham at Enzie twenty miles east of Nairn with no clear victor. Both sides retreated. By late summer Edward held no control over Nairn or its castle or any castle north of the River Forth other than Dundee.[34][5]: 110-112

Sir Andrew de Rathe of Nairn continued to act as envoy for Edward I during this time convincing Edward I to dispatch an army of 40,000 troops. Sir Andrew Moray and his army, some of whom were men from Nairn, joined William Wallace in his march south defeating the English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge and it is believed Moray was injured at Stirling Bridge and died of his injuries in November 1297.[35][36]

14th Century

Rise of Robert the Bruce

In 1303 Edward I brought nearly his full army largely unopposed with many counties burned and residents murdered along this route. By the 10th of September reaching Elgin east of Nairn moving then to Kinloss on the 13th and Lochindorb (Scottish Gaelic: Loch nan Doirb) 18 miles south of Nairn. During his stay in Lochindorb Castle Nairn was requisitioned supplies (26 cattle, 26 sheep and 40 pigs) to feed this extensive army. Nairn Castle once again came under possession of English troops at this time.

On October 4 Edward I left Moray returning south now with English troops in all major townships and castles.[5]: 112-114 Nairn Castle was raided in autumn of this same year by Sir Climes of Ross. Cavalry dashed down the High Street of Nairn at night from the direction of Redhill or as it is now known The Brae. After dismounting they set light to a neighbouring cottage with a stolen oil lantern, stormed the gates and slew the castles governor. [5]: 112-114

“The Knight Climes of Ross and the barons, who were with him, came into the Murray Lands with their good chivalry. The good Knight took the house of Nairn, and slew the Captain and Garrison. From thence they passed into Buchan." [37]

By February 1304 all the leading Scots, except for William Wallace, surrendered to Edward I. William Wallace is believed to have passed through Nairn on his way north in 1304 stopping at Nairn Castle before crossing the Moray firth at Ardersier 12 miles west of Nairn. Visible from Nairn is Wallack Slack where William Wallace defeated a large English force detailed in Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland.[38] It was shortly after this time that Sir William Wallace was forced into hiding and Alexander Wiseman appointed as the new Sheriff of Forres and Nairn in 1305.

Robert the Bruce, former Guardian of Scotland in 1305 was accused of treason by Edward I and returned to Scotland. On 25 March 1306 he was crowned Robert I, King of Scots witnessed by the bishops of Moray and as such the new ruler of Nairn. The office of sheriff and constable of the castle became hereditary in the family of Cawdor. The lands and town itself were granted by Robert I to his brother-in-law, Hugh, Earl of Ross, and are believed to have continued in the possession of that family till the forfeiture of John, Earl of Ross and Lord of the Isles, in 1475.[19]

Rule of King Robert I

The army of Edward I once again marched to Scotland in 1306, defeating Robert the Bruce on 19 June 1306 at the Battle of Methven and with great brutality imprisoned and murdered may of the Bruce family. During this time the specific governance of Nairn is unclear but believed to be under English rule as in February 1307 Robert the Bruce gathered forces securing many victories including in May burning Nairn Castle. Edward I had himself in July moved north to the Scottish borders to meet this threat where he died from dysentery. His brutal attacks earned him the epithet "Hammer of the Scots" in history. Robert the Bruce remained in Moray taking Duffus Castle 10 miles east of Nairn and Balvenie Castle 20 miles south.[39][40]

Shortly after the Death of Edward I, King Robert I met with a key moment in history just outside of Nairn. On October 8, 1308 William II, Earl of Ross, the leader of the army of Edward I in the North of Scotland during his war with King Robert I met with Robert to submit to his rule. While Robert was in exile during this was William had entered a church where his wife Isabella of Mar was sheltering and killed all her servants in front of her and their daughter Marjorie Bruce. Under his watch both Isabella and Marjorie were delivered to England to be held captive inclusive of the time the two met here outside Nairn. In attendance were David Stewart, Bishop of Moray and Walter Herok, Dean or Moray both of whom had also suffered under William and Edward. Robert accepted Williams surrender and the two fight together frequently throughout the continuation of the war and at the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn.[41][42]

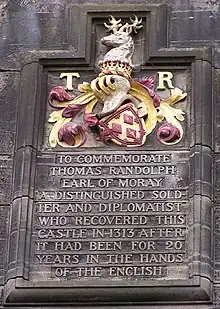

It was in 1310 in Nairn that King Robert I wrote the charter naming William, Thane of Cawdor, a charter still held in Cawdor Castle, and as such Sheriffdom of Nairn. William was the son of Donald Calder, the first Thane of Cawdor. The title of Earl of Moray was created in 1312 by King Robert I for his nephew Earl Thomas Randolph including the burghs of Nairn, Forres and Elgin. This caused confusion in control over Nairn as Hugh, Earl of Ross still retained overall control of the lands of the Earl of Moray including the office of Sheriff of Nairn and Constable of Nairn Castle. Permission was needed from Hugh, Earl of Ross for land sales. This control over Moray and Hugh's marriage to Robert's daughter made him a very influential figure if not the most influential next to the King.[43][5]: 156-158

"Additionally, he (King Robert I) wills and grants that the burghs and his burgesses of Elgin, Forres and Invernairn should have the same liberties as they held in the time of Alexander (III), king of Scotland, and in the time of King Robert himself."

— Gift of earldom of Moray with various liberties (1312)[44]

Scotland lead by Robert the Bruce was at war with England under Edward II and Edward III through to 1328 when Edward III signed the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton recognising Scotland as an independent kingdom, and Robert the Bruce as its king. Scotland, and Nairn continued to be under the rule of King Robert I until his death on 7 June 1329 succeeded by David II.

Rule of King David II

King David II of Scotland was King of Scots at age five after the death of his father King Robert I on 7 June 1329. Earl Thomas Randolph of Moray was named Guardian of Scotland placing considerable power within Nairn, Forres and Elgin. He was to be regent until the king was old enough to rule which was the command of King Robert I before his death. The Earl of Moray died just three years later on 20 July 1332, during his time as regent he was described in the below pen portrait.

He was of moderate stature

And well-formed in measure

With a broad face, pleasant and fair.

Courteous in bearing and debonair

And of fittingly confident bearing.

Loyalty he loved above all things,

Falshood, treason, and felony

He stood against always earnestly.

He exalted honour and liberality

And always strove for righteousness.

In company, he was caring

And therewith even loving

And good knights he loved always,

For if I speak the truth

He was full of good spirits

And made of all the virtues.— John Barbour, the Brus

The death of Earl Thomas Randolph proved to be a turning point in Scottish history as his successor Domhnall II, Earl of Mar elected on 2 August 1332 had no military talent and was very quickly killed by 11 August 1332 in an invasion by Edward Balliol, supported by Edward III of England starting the Second War of Scottish Independence. As such it is very unlikely this new Regent ever spent time as Regent in Nairn. Edward Balliol was crowned 24 of September 1332 but fled to England three months later, returning in 1333 with the full public support of Edward III of England. Thomas Randolph, 2nd Earl of Moray was killed in the initial assault succeeded by his brother John Randolph, 3rd Earl of Moray.

Sir Andrew Moray who fought with William Wallace, the only Scottish Noble who had never submitted to England travelled through Nairn raising an army to support the young King. Now Regent he spent significant time in the Nairn area and likely used the supportive Nairn as a base with which to attack nearby Lochindorb and Kildrummy Castle. Edward III of England and his army decimated Nairn. Burning all nearby towns and the city of Inverness as well as the fields and food stores of Nairn. Garrisons of English troops were left in fortified locations such as Nairn Castle as Edwards main army moved south but were overthrown by Sir Andrew Moray. Much of Scotland including Nairn was facing famine following the destruction left by the army of Edward. The prominence of herring fishing in Nairn was a decisive help in turning this famine.[5]: 144-146 [45]

.jpg.webp)

Many Scottish nobles and common people of Nairn were killed in the subsequent Battle of Halidon Hill in July 1333 where John Randolph, 3rd Earl of Moray commanded the first division of the Scots' Army and captured the commander of the English forces in Scotland. Sir William Rose, Baron of Kilravock local to Nairn was killed in the battle as was Hugh, Earl of Ross who still retained overall control of Nairn with his son William III, Earl of Ross succeeding him. The Earl of Moray survived the heavy defeat and continued to govern Nairn and was named co-regent.[46] Edward Balliol attempted multiple times to invade Scotland but was rebuffed despite King David II of Scotland being in exile and made his final attempt in 1335.[47][5]: 140-144

As the war continued John Randolph, 3rd Earl of Moray was captured in 1335 and governance of Nairn fell back to the crown. After being free in 1341 he immediately joined the army once more and by 1342 England was engaged in both this war and The Hundred Years' War and had lost all control in Scotland. The Earl of Moray started preparing for the February 1346 invasion of England. William III, Earl of Ross retained control over Nairn at this time and significantly assassinated one of his rivals Ranald of the Isles causing the King to chastise him and his leaving the field of battle with his army. Likewise the troops of Ranald of the Isles left. Leaving the Scottish army much weaker for the upcoming invasion. When John Randolph, 3rd Earl of Moray died on 17 October 1346 in the Battle of Neville's Cross without any children the crown once again took control of the Earldom. King David II of Scotland was also however captured in this battle. For several years control over Nairn was given to Agnes, Countess of Dunbar known as "Black Agnes" for her dark complexion however William III, Earl of Ross still retained all the overall ownership of his father. Confusing this ownership further the 2nd Thane of Cawdor died, to be replaced in 1350 by William Calder, 3rd Thane of Cawdor. Each of which having a facet of hierarchical control over Nairn. This was a period of truce as England fought the Hundred Years' War and Scotland's fractional structure left no organisation until 1355 when Scotland broke the truce and invaded England. The Treaty of Berwick was signed in 1357 ending the war.[5]: 155-159

King David II of Scotland was returned to Scotland in 1363. During his captivity William III, Earl of Ross had further lost the favour of the King and the Highlands under his control were in revolt. Peace was reached in 1368 but this had considerable toll on Nairn combined with the previous wars toll. In the following years the royal finances prosperous but the common man of Nairn was suffering from continued food shortages and high taxation. Control of Nairn remained with the crown under technicality but in practicality Agnes, Countess of Dunbar governed as Earl and the revolt ended the control of the Earl of Ross over Agnes and the Earl of Moray title. King David II of Scotland died in 22 February 1371. [5]: 154-155 [48]

The Wolf of Badenoch

On attending Inverness on 24 June 1371 King Robert II is noted to have removed the lands and power of William III, Earl of Ross who now had no control over his own lands of Ross and only retained his official place in Nairn until his death in 1372. It was in this same year William Calder, 3rd Thane of Cawdor who held the Sheriffship and Constabulary of Nairn started construction on the tower of Cawdor Castle.[16][15]

"When my Lord the King came to the town of Inverness, he found me without any land or Lordship, my whole Earldom of Ross seized and recognosced."

— Charters and Notes, Spalding Club, Aberdeen (1864)[49]

Control of Nairn was passed to John Dunbar, Earl of Moray, son of Agnes in 1374 on her death. The Sheriff of Nairn and Constable of Nairn Castle titles were passed to Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan better known as 'The Wolf of Badenoch' by marriage to William's daughter becoming jure uxoris Earl of Ross in 1382. Alexander ruled these territories with the help of his own private cateran forces, building up resentment among other land owners and this included Alexander Bur, Bishop of Moray.[50] Both the Alexander Bur, Bishop of Moray and Alexander de Kininmund Bishop of Aberdeen were in dispute with Alexander Stewart regarding the strain that his cateran followers were putting on church lands and tenants. Both were unable to appeal as expected due as the point of appeal would have been The Wolf of Badenoch himself. As such they had to appeal to the King directly.[51]

By 1384 the appeals of the Bishops, neighbouring nobility and the people including John Dunbar, Earl of Moray as the cateran of Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan had killed some of his men had reached the king. Sir David Lindsay set a claim to Strathnairn and Alexander's brother David Stewart claimed Urquhart was being held unlawfully. Despite this Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan retained his title and lands, even gaining more land from the Earl of Moray in Bona.

Alexander Stewart was named Justiciar North of the Forth in 1387. Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan had complete control of Nairn and most of the highlands until 1388 when Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany, the king's son, removed his titles. Alexander Bur, Bishop of Moray demanded Alexander Stewart return to his wife having left her for another woman. While he agreed he did not return and so the marriage was annulled losing his claim to his former wife's lands that had granted him control over Nairn. Alexander Leslie, Earl of Ross reclaimed his lands of Ross and John Dunbar, Earl of Moray his of Moray and Nairn.[52][53]

King Robert II died on 19 April 1390 with his son Robert III of Scotland taking the crown. It was in May and June 1390, shortly after his father's death that Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan, 'The Wolf of Badenoch' would seek revenge. John Dunbar, Earl of Moray and Sir David Lindsay had travelled south out of Moray to England to attend a tourney. Alexander Bur, Bishop of Moray was the source of The Wolf's revenge as culminating in the destruction of parts of Nairn and Forres in May, predominantly church lands, and then Elgin with its cathedral set on fire and burned down in June. Three sons of Alexander Stewart were imprisoned in Stirling Castle from 1396 to 1402, excommunicated The Wolf of Badenoch died in 1405.[54][55]

15th Century

James I of Scotland

Sheriffship and Constabulary of Nairn continued to be in the family line of Calder under Andrew Calder, 4th Thane of Cawdor whose lands now included Raite. Robert III of Scotland died on 4 April 1406 passing his crown to James I of Scotland. With support from Donald of Islay, Lord of the Isles, Mariota pressed her claim to the title of Countess of Ross sending emissaries to James I of Scotland seeking support and she received it from King Henry IV of England. It was in November 1406 that the title and Sherifdom of Nairn passed to Donald Calder, 5th Thane of Cawdor.[16][15]

Nairn was invaded in 1411 by Donald of Islay, Lord of the Isles who had that year forcibly claimed the lands of Ross with an army of 10,000 men and captured Inverness which had been partly burned in the process. As he claimed the title of Earl of Ross and the Sheriffdom of Nairn was within this title he called on the men of Nairn to join his army and they had no choice but to agree or face certain death. After bringing his army to Aberdeen he was forced to retreat back north. After being pursued by Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany the titles of Earl of Ross were in 1415 returned to Euphemia II, Countess of Ross who surrendered them to the Duke of Albany, who in turn passed these on to his son John Stewart, Earl of Buchan inclusive of the Shire and Castle of Nairn. In 1419 he was sent to France to fight in the Hundred Years' War where he died on 17 August 1424.[5]: 160-165 [56][57]

Despite the invasions it appears the coffers of the Cawdor estate as financed by Nairn were rich during this period. The estate was expanded to include Dunmaglass in Strathnairn, Moy near Forres and Urchany Beg within the Barony of Fothryves and parish of Cawdor by 1421. Though these lands were still under control of the Earl of Ross and the King ultimately.[16][15]

James I of Scotland returned to Scotland from English captivity in 1424 allied with Alexander of Islay who had claims to the title Earl of Ross and Sheriff of Nairn against Murdoch Stewart, Duke of Albany, Governor of Scotland. By 1425 King James I had travelled north to Inverness holding Parliament and summoning all Highland Chieftains. As they entered each chieftain was seized, captured and imprisoned including Alexander of Islay and his mother Mariota with fifty in total being taken. Alexander was allowed to go free but returned in 1429 with an army to burn Inverness and was defeated. From August 1429 the king delegated royal authority to Alexander Stewart, Earl of Mar for the keeping of the peace in the north and west.[58][5]: 163-166

James I died on 21 February 1437 passing his title on to James II of Scotland and likewise the title of Thane of Cawdor was passed in 1442 to William Calder, 6th Thane of Cawdor and with it the Offices of Sheriff and Constable of Nairn.

James II of Scotland

Under James II in 1435 Alexander of Islay took the title Earl of Ross largely unopposed and with it sheriffdom of Nairn. With William Fleming named as Burgess of Nairn, he likely took much of the daily running and governance of the town. By February 1439 Alexander was named Justiciar of Scotia the legal authority in Scotland. Based on his charters it is indicated that Alexander of Islay, Earl of Ross was chiefly based at the castles of Dingwall and Inverness, and rarely anywhere else until his death in 1449.[59][60]

William Douglas, 8th Earl of Douglas, Archibald Douglas, Earl of Moray, Alexander Lindsay, 4th Earl of Crawford and John of Islay, Earl of Ross had formed a pact 'against all men, including the king' which the King had become aware of. John taking the Royal Castles of taking the royal castles of Inverness, Urquhart and Ruthven. Archibald Douglas was killed fighting the king's supporters at the Battle of Arkinholm in 1445 and the title Earl of Moray was once again passed through treason to the crown. John of Islay, Earl of Ross was sent word via the sheriff-depute of Nairn in February 1452 that he had been summoned to answer for his treason by the King along with William Douglas, 8th Earl of Douglas. John did not obey the summons, William did but refused the King and with assistance the King killed William .[61][5]: 165-166

William, 6th Thane of Cawdor was given instruction to fortify Cawdor Castle in 1454. Having been appointed Joint Crown Chamberlain North of the Spey, William was described by the King as "dilectus familiaris scutifer" or 'beloved familiar squire'. Where once he was squire of James II, now he was given financial control over the lands and revenue of the Earldom of Moray. The Crawford estates in Strathnairn, the Petty and Ormond possessions. The sheriffdom of Elgin, Fores, Nairn and Inverness, and the maintenance and upkeep of all the King's castles in the area. By 1458 through is son's marriage the lands under control of the Thane of Cawdor covered large amounts of the North of Scotland and believed to be the most extensive of any lord.[5]: 176 [16]

James III of Scotland

James III of Scotland started his reign on 3 August 1460 at which time the Sheriffdom of Nairn was held by the William Calder, 6th Thane of Cawdor under control of the Earl of Ross. John of Islay, Earl of Ross was pardoned in July 1477 having most of his lands returned with the exception of the Earldom of Ross and the offices of Sheriff of Inverness and Nairn. This was the last point where the Earldom of Ross was overarching to the sheriffdom of Nairn. At this time William Calder, 7th Thane of Cawdor received a Crown charter drafted in Edinburgh, 29 May 1476, granting to him all his lands into one thanage of Cawdor. He also received permanent hereditary Sheriffdom and Keeper of the King's castle at Nairn.[5]: 166 [62]

Calder vs Campbell

In 1492 the Church and the Andrew Stewart, Bishop of Moray held large amount of land and power within Nairn. So much so that when the Baron of Kilravock raise a dispute over land boundaries a jury of arbiters was formed. They met in Nairn Parish church. Not accepting the ruling of this jury it took an order from King James IV of Scotland for the Bishop of Moray to desist. On the contrary to the lifestyle of high wealth of the Bishop and Dean of Moray, the clergy did not have a high standard of life.[5]: 135-140 [63]

King James VI came to Inverness with charges against William Calder, 7th Thane of Cawdor in 1492. He had taken the law into his own hands killing four men in Inverness for the theft of cattle. Pardoned of this crime be handed his title down to his son John Calder in 1493. William Calder is however once again accused in April 1494. Tried in the court of Aberdeen they were sentenced to be beheaded. When King James II attended Inverness in October William Calder was once again pardoned and his son John given the Royal Charter to continue his Thanage of Cawdor and his title as Sheriff of Nairn. John died shortly after in December 1494. [5]: 183-184 [16]

Despite substantial legal protest of William Calder, 7th Thane of Cawdor, his son's title was passed to Muriel Calder of Cawdor in 1502 while she was a child. This would have succeeded but William was in the midst of his own legal issues and thus prevented from taking the child himself. John Kilravock took the infant and her mother to Kilravock Castle to protect them from being murdered by her uncles and secure marriage to his Grandson. This plan was defeated by Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll who as Justice General in Scotland had John Kilravock charged with a crime and demanded 800 merks or the delivery of the infant Muriel as payment. He chose the latter of these options delivering Muriel to the Earl of Argyll. King James IV by Royal grant on 16 January 1495 named Archibald Campbell and Hugh Rose of Kilravock as Muriel's guardians and ward of her marriage.[16][15]

16th Century

Calder vs Campbell

The lands of Cawdor in Nairn during were taken by John Calder, Chantor of Ross, for his nephew the William Calder, Vicar of Evan as well as the Sheriffdom of Nairn and Nairn Castle. The Sheriffdom of Nairn was resigned by William Calder, Vicar of Evan to Hugh Calder in 1510 where he became Sheriff of Nairn and Constable of the King's Castle.[5]: 183-184

"...the crofts beside Belmakeithe, beyond the water of Nairn, forgayne the castle of the sammyn ; also, of six roods THE OLD CALDKRS. 1ST lying within the galois, two roods in the Millbank, and two- roods in the Skaytrawe, and also of 30d of annual of Cristane Flemyng's land, and of Criste Cummyng's bigging 2s of annual, and of Henry Dallas's land of Cantray 2s of annual"

The court of Nairn held at Nairn, 16th of August 1506

Archibald Campbell, 2nd earl of Argyll, ensured he was named King's Crowner within Nairn giving him equal power to that of the Sheriff of Nairn. This retained connection for Muriel allowing him to intervene if the taking of Cawdor lands continued past a point he would accept. Muriel returned to her father's estate on 3 Mar 1502 with her soon to be husband. She was married to Sir John Campbell, 3rd son of the 2d Earl of Argyll in 1510 and by 1513 King James IV was succeeded by James V of Scotland.[16]

King James V

Sir John Campbell took up residence in Nairn in late 1521 but moved south to kill MacLean of Duart who had tried to murder the Thane's sister and MacLean's wife. Sir John Campbell and Lady Muriel in December 1524 took permanent residence in Cawdor Castle. On the death of Muriel's uncles Sir John purchased their lands from the crown. By 1528 he had purchased the Sheriffdom of Nairn from Hugh Calder for a sum of 8 merks of land in Balmakeith adding to his existing land in the Househill, Millbank and King's Steps areas of Nairn. He added to this extensive lands in Moy, Geddes, Brackla, Daviot and Strathnairn and Raite. Attending Edinburgh a Royal Charter was produced shortly thereafter stating the lands owned by Lady Muriel, 9th Thane (Thaness) of Cawdor as a formal thanage and free barony.[16][5]: 188-189

King James V began his reign by tightening control over royal estates and increasing profits of justice, customs and feudal rights. He also placed heavy taxation on churches. Spending large amounts of his time on diplomatic trips to France, the Western Isles and England, he was rarely in Nairn but his impact was felt on the coffers of the church of Nairn headed by Andrew Forman, Bishop of Moray and Gavin Dunbar (archbishop of Glasgow), Dean of Moray. James Stewart was granted the title Earl of Moray inclusive of Nairn in 1531. King James V had committed to France and Catholicism, while England under Henry VIII was committed to Scottish Reformation in line with the English Reformation placing the two at war with the first battles taking place in August 1542 this did secure him the support of the Bishop of Moray and Dean of Moray but not the Earl. James V died at Falkland Palace on 14 December 1542 with the war ongoing.[64][5]: 220-225

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots, daughter of King James V reigned over Scotland from 1542 and had strong connections to Nairn. The soon to be Earl of Moray, James Stewart was the bastard half-brother of Mary, Queen of Scots. On ascending to the throne internal political struggle lead to civil war with much of the fighting in the south reaching as high north as Dundee in 1549. Mary of Guise, the queens mother had cultivated a policy of limited toleration of Protestants but firm support for France and Catholicism.[65] Mary married the Dauphin in 1558 furthering tensions. By 1559 James Stewart who would become the 1st Earl of Moray had become a strong proponent of Scottish Reformation, a leader of the Lords of the Congregation. Both of these factors lead to wide dissatisfaction in the churches of Nairn with the current state of rule. James was so influential that he represented the Lords at the Treaty of Berwick prompting England's invasion.[66][5]: 220-225

By the Act of 1561 Queen Mary conferred the property of the religious houses to the crown and detailed were the valuations of the lands in Moray.

- The Dean of Murray for Auldearn, Nairn, and lands, £130, equal to 650 bolls of grain 'at 4s per boll

- The Vicar of Nairn £6, equal to 200 bolls ;

- The sub-chantor for Rafford and Ardclach £263 Os 8d, equal to 1316 bolls

- The Vicar of Ardclach £10, equal to 40 bolls.

Mary travelled north to Inverness. From Edinburgh on the 11th of August, passing Aberdeen and through to Nairn in August in 1562. The first time the young queen had travelled so far north and she had rounds to make. Visiting various Nairn gentry and religious figures in Auldearn. The first bridge in Nairn had not yet been built and as such Queen Mary had to ford the River Nairn. John Rose the provost of the time meeting the queen on Nairn High Street, the only true street in Nairn at the time, likely with the magistrates and sheriff welcomed her where she would view Nairn Castle. The Castle at the time still retaining it's figure as a fortified building in prominent position. She moved on to Inverness later that day not stopping in Nairn overnight.[5][68]

Queen Mary was denied admittance to the Castle of Inverness by the word of George Gordon, 4th Earl of Huntly, an exceptionally powerful lord of the time and one who was out of favour with the queen. He believed she was to subdue this power and so denied her. Many of the local nobility of Nairn, Inverness and the surrounding area became aware and welcomed the queen. The castle was quickly surrendered and the captain inside hung. James Stewart was named the 1st Earl of Moray in Aberdeen later that year on her return journey south. The Earl of Huntley had made clear his intention to rebel. Mary joined with the Earl of Moray in the destruction of Lord Huntly and his heirs. Lord Huntly was Scotland's leading Catholic magnate and with him no longer in control, the reformation had lost a large blocking point in its progression.[68]

Queen Mary was married to Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, a leading Catholic, in July 1565. The Earl of Moray opposed the marriage and rebelled. He was marked as an outlaw and Scotland was once again facing Civil War with the people of Nairn called to arms but the rebellion was short lived and the Earl fled to England in October only to later be pardoned by the Queen. Lord Darnley wished more power, attempted to become co-sovereign, entered secret conspiracy with Protestant lords including Moray but was murdered by February 1567. Mary was abducted by the man believed to have murdered her husband in April and the two were married in a Protestant ceremony in May. This recent turmoil had caused unrest for both Protestants and Catholics.[69][68]

The Earl of Moray and Regent of Scotland

Mary was forced to abdicate in July 1567 to her one-year-old son James. James Stewart, the 1st Earl of Moray, was named Regent of Scotland once again placing significant control over the history of Scotland in the hands of a man of Nairn. Moray sold the Jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots to raise money for reformation and his own interests.[70][71]

With the Earl of Moray in regency, nothing stood in the way of continued reformation in Scotland. The Reformation of Scotland's churches left them struggling for clergy, it was written by John Knox below of the state of affairs in Scottish reformed churches of the time.[5]

"To the kirks where no ministers can be had presently, must be appointed the most apt men that distinctly can read the common prayers and the scriptures, to exercise both themselves and the kirk."

— John Knox, The First Book of Discipline (1972)

This was less an issue for the churches of Nairn as many of those converted from Catholicism. The first Protestant minister of Nairn being Mr John Young in 1568 with William Reoch coming in 1570 and Allan Mackintosh coming in 1581. The existing Dean of Moray, Alexander Dunbar retained control overall.

In May 1568 Queen Mary had escaped her imprisonment and rallied allies, as did Moray defeating her forces at the Battle of Langside and Mary was forced to flee to England. James Stewart embarked on multiple military operations to attack those who supported her in Scotland. He was assassinated in January 1570 being unable to remove the support for Queen Mary. He was the first head of state to be assassinated by firearm. Subsequent regents had no relation to Nairn but the title of Earl of Moray was passed to Elizabeth Stuart, 2nd Countess of Moray the daughter of James.[72]

James VI and I

While Sir John the Thane of Cawdor died in 1546, Lady Muriel survived until 1575 in this position of Thane and Sheriff of Nairn. She outlived her husband, son and King James V. Thanedom passed to her grandson, John Campbell. He had little interest in Cawdor and had become an absentee Thane, spending his time in Argyleshire. Cawdor Castle was deserted with decapitated walls and roofs. The trustees of the estate meant to take control of the lands themselves. John sold part of his estate to Simon Fraser, 6th Lord Lovat, in return to fund his heavy taxation and lifestyle on Islay, an island off the west coast of Scotland. [16][5]: 188-189

King James VI was named as an adult ruler and free from regency by 19 October 1579 at fifteen. At the time the control of Nairn was in the hands of the Thane of Cawdor Lady Muriel, with the Earldom of Moray superseding under Elizabeth Stuart, 2nd Countess of Moray.

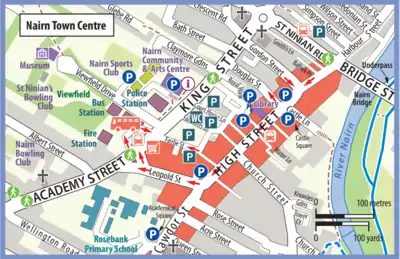

King James VI visited the Royal Burgh of Nairn in 1589 and is said to have later remarked that the High Street was so long that the people at either end spoke different languages, Scottish Gaelic and Scots. The landward farmers and the fishing families at the harbour end spoke Doric, and the highlanders spoke Gaelic.[73]

"sae lang that the inhabitants of the one end did not understand the language spoken at the other".

— James VI of Scotland [19]

The King attended the North Berwick witch trials, the first major witch trials in early modern Scotland under the Witchcraft Act 1563. James became concerned with the threat posed by witches. This support from the crown was a significant factor in the witch trials in early modern Scotland which killed many in Nairn.

On February 4, 1591, John Campbell, 10th Thane of Cawdor and Sheriff of Nairn was murdered by a neighbour. In this same year The Countess of Moray had died in childbirth passing on this title to James Stewart, 2nd Earl of Moray.

17th to 19th century

After rapid changes of hands control over the Thanedom of Cawdor and Sheriff of Nairn title came to Sir Colin "Tutor of Cawdor" Campbell who invested money into re-establishing the Castle to its former condition then to Sir Hugh Campbell, 15th Thane of Cawdor his son in 1642.[16]

Wars of the Roses of Belivat

Nairn at the start of the 17th century was a place of much conflict but not a conflict of armies, of clans. Prominent families of Nairn took sides in a conflict between the Roses of Belivat and the Sheriff of Nairn and The Lords Council. On May 27, 1596, two members of the Falconer family raised issues with members of the Rose family of Belivat for the harrying their tenants and violent theft of cattle and horses. The Roses did not attend when summoned by the council, the council taking no action the Roses in September attacked. Taking weaponry they attacked the tenants of Falconer. Breaking open the doors of their farms while they slept the stole their goods. The Rose of Belivat were named rebels by The Lords Council.

Hostilities continued as David Rose was ejected by the Sheriff of Nairn from his land following legal proceedings over ownership. Two hundred supporters of David Rose were raised in 1598 driving any new tenants from his former lands. Took all goods and burned any houses found there down. The Roses continued to use their numbers to confront any officers sent to them and to attack those families they deemed to have slighted them. Having not received the support they expected from the crown or legal system prominent families such as the Dunbars and the Falconers raised supporters of their own. The supporters of the Dunbars burned property connected with the roses and even assaulted and threatened the Baron of Kilravock, burning his house in Geddes for his lack of action.

"The Roses of Belivat were a bold, daring, and headstrong people, who put up with no injuries or affronts, but warmly resented any wrong, real or supposed."

— Lachlan Shaw (1775)[23], The History of the Province of Moray

During this time Nairn having a connection to the Roses throughout, most prominently through the Provost John Rose, was in danger of assault. Rose of Belivat had a home himself in Nairn in the Millbank area. Market-day in Nairn later this year nearly became a sight of a bloody and violent battle as both parties had attended. The Baron of Kilravock and Laird of Mackintosh settling both. Over years allies from both sides came from as far as Lochaber and Strathspey. David Rose was hung by an agent of the Nairn lords and Dunbar, Laird of Tarbet and Dunphail was murdered by the Roses. This murder brought the ongoing hostilities to the attention of the government and an Act of the Privy Council was put in place to subdue the rebellious Roses.

The Baron of Kilravock was instructed by The Lords Council to apprehend members of his own family of Rose. He denied on grounds they had become too large for his own ability to control. He was still held accountable and imprisoned for his inability to conduct his duties only being freed in 1603 by order of King James with instructions to return to his castle and enact the king's justice.

The roving band of Nairn nobility that was the Roses had taken residence in Strathdearn, modern day Tomatin near Inverness the lands of the Mackintosh's. It was not until 1611 that an Act was passed demanding he remove them from his lands. The Roses defined this and continued to raid into Nairn with focus placed on the Dunbars. The Sheriff of Nairn, a Dunbar, burned down the historic home of the Laird of Belivat and the Roses in Fleenas. Several members of Clan Rose were executed or imprisoned. Much of the leadership was handled in this way and the remaining members of Clan Rose made peace with Clan Dunbar over several years bringing a gentle and slow end to a bloody and violent period of Nairn history.[5]: 236-268 [74]

During 1660 through 1670 Cawdor Castle was owned by Sir Hugh Campbell and his descendants until 1726. It was then purchased by Duncan Campbell of Shawfield.[16]

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

From 1644 to 1645 James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose led the Royalists in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms on 9 May 1645, the battle of Auldearn was fought two miles south east of Nairn, between Royalists and Covenanters. This battle resulted in a victory for the royalists, the battlefield has been included in the Inventory of Historic Battlefields in Scotland and is protected by Historic Scotland under the Historic Environment (Amendment) Act 2011.[75] The Laird of Calder's house and lands in Nairn were burned, and his goods plundered by Montrose as was the nearby town of Elgin following the battle as he believed them to have supported the Covenant.[4]: 6

During the Jacobite rising of 1715 forced levies of arms, horses, or forage were made of the people of Nairn. While some gentry did join the Jacobite cause, on the whole the district stood firm in its adherence to the Hanoverian cause despite the close proximity to the raised Jacobite army in Braemar under John Erskine, Earl of Mar.[4]: 6

After passing through Elgin on Sunday the 13th of April 1746, Duke of Cumberland on the 14th approached Nairn, Lord John Drummond troops attempted to oppose the duke's entrance to the town but was quickly dissuaded by the appearance of the main body of the Hanoverian army. The duke's forces, which numbered about 7000 foot, 2000 horse and a train of artillery entered Nairn later that day. Part of the troops were lodged in the tolbooth and other buildings. The old Bufs bivouacked on the haugh on the east side of the river; but the main body had to march to Balblair, about a mile west of the town, where they formed a camp as the town could not support such a large retinue of troops. Duke of Cumberland stayed in Nairn the night before the battle of Culloden on the 15th of April 1746 in Laird of Kilravocks town-house, Tuesday the 15th being his birthday. Lord George Murray suggested a night attack on the encampment in Nairn which could have taken the place in history of the battle of Culloden.[4]: 6 [76]

After the battle of Auldearn, Montrose's men burned and destroyed Cawdor's house in the town. Following the abolition of hereditary jurisdictions in 1747, the office of sheriff and constable of the castle ceased to be hereditary titles in the family of Cawdor.[19]

170 years from the comments of King James VI of Scotland, in 1773 Samuel Johnson noted the continuation of the Gaelic language in Nairn as part of its culture.

"At Nairn we may fix the verge of the Highlands; for here I first saw peat fires, and first heard the Erse language."

— Samuel Johnson, A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland (1775) [77]

19th Century

In 1820 a wharf and harbour were constructed at the mouth of the River Nairn by Thomas Telford[78] Where they remain having been built for a cost of £5500. In 1882 there- were 91 boats registered to the harbour, of which 52 were first—class, 37 second-class, and 2 third-class, and connected with them were 250 resident fisher men and boys. The majority of boats used for herring-fishing from ports farther down the firth. Common exports of this time are timber, corn, potatoes, eggs, smoked haddocks, and- freestone; and imports of foodstuffs, soft-goods, hardware, lime, manures, and coal.[19]

Mouth of the River Nairn

Mouth of the River Nairn Harbour entrance

Harbour entrance Inner Harbour facing sea

Inner Harbour facing sea Inner Harbour facing land

Inner Harbour facing land

Its believed the first Newspaper of the local area was produced in 1845 under the name Nairnshire Mirror, and General Advertiser. Printed from 1845 to 1846 and again 1848–1854. [79] The second came in 1853 known as the Nairnshire Telegraph locally and more formally The Nairnshire Telegraph and General Advertiser for the Northern Counties which continued to publish until 1939.[4]: 384 [80]

While the Great North of Scotland Railway had formed in 1845 connecting Aberdeen to Keith, it wasn't until 7 November 1855 that Nairn was connected to Inverness by rail but not connected to the existing line to Aberdeen stopping at Keith. In 1857 this line was extended to Forres and then connecting on to Aberdeen on 17 May 1861.[81][82]

It was not until the 1860s that Nairn became a respectable and popular holiday town. Dr John Grigor (a statue of whom is located at Viewfield) was gifted a house in this coastal town and spent his retirement there. He valued its warm climate and advised his wealthy clients to holiday there. Following the opening of the Nairn railway station in 1855, new houses and hotels were built in the elegant West End. The station is on the Aberdeen to Inverness Line. Originally this was the last stop on the line from London due to the inhospitable terrain on what is now the main Dava branch line to Inverness.

From 1880 some of the history of Nairn can be found through the founding of the Moray and Nairn Express newspaper, then renamed to The Northern Scot. While the more localised St Ninian Press was founded in 1892 by a local bookseller named John Fraser is no longer in circulation, The Norther Scot continues to be published weekly on a Friday.[4]: 384 [83]

20th Century

Nairn has an expanse of sand beaches that were used extensively in training exercises for the Normandy landings during World War II. The beaches around Nairn had landmines planted, during clearance operations in 1945 by 11th Company, Bomb Disposal, Royal Engineers. High pressure water jetting was used to displace shingle on top of mines to make clearance easier. Notably during this period two German spies who had been dropped by U-boat in the Moray Firth were arrested at Nairn railway station attempting to board a train to Inverness.

In July 1987 the Nairnshire Telegraph name was once again used as a local Newspaper publisher. Incorporated by Maureen Joan Bain and Colin Bain of Nairn where it was based on Leopold Street.[84]

References

- ↑ "NatureScot landscape character assessment". Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ↑ "MHG7192 - Axes and flint tools - Slagachorrie". Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ↑ "MHG7075 - Banchor". Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Charles Rampini LL.D (1898). The County Histories of Scotland, Moray and Nairn. William Blackwood and Sons. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 Bain, George (1893). History of Nairnshire. "Telegraph" Office. pp. 2–5.

- ↑ Ptolemy Atlas, Strasburg Edition.

- ↑ "Canmore Archaeology Notes". 1965. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ↑ Camden, William. Camden's Britannia vol iii. p. 430.

- ↑ R. W. Chambers and Walter W. Seton (1919). "Bellenden's Translation of the History of Hector Boece". The Scottish Historical Review. Edinburgh University Press. 17 (65): 5–15. JSTOR 25519192.

- ↑ John Grant, William Leslie (1798). A Survey of the Province of Moray Historical, Geographical, and Political. p. 65.

- ↑ O'Neill, Pamela (2007). Six degrees of whiteness: "Finbarr, Finnian, Finnian, Ninian, Candida Casa and Hwiterne (PDF). pp. 259–268.

- ↑ Mc Carthy, Daniel P.,'The Chronology of Saint Columba's Life’, in Moran, P. & Warntjes, I. (eds), Early Medieval Ireland and Europe: Chronology, Contacts, Scholarship - Festschrift for Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2015), pp. 3–32

- ↑ Duncan, A. A. M. (2002). Kingship of the Scots. Edinburgh University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780748616268.

- ↑ Broun, D (2004). "Duncan I [Donnchad ua Maíl Choluim]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8209. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anderson, William (1877). Scottish Nation. Fullarton.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 John Frederick Vaughan Campbell Cawdor (2d earl of Cawdor) (1742). The Book of the Thanes of Cawdor A Series of Papers Selected from the Charter Room at Cawdor. 1236-1742. pp. li.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dowden, John (1912). The Bishops of Scotland.

- ↑ A.O. Anderson, Scottish Annals, p. 167; Anderson uses the word "earldom", but Orderic used the word ducatum, duchy.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Groome, Francis Hindes, 1851-1902 (1895). Ordnance gazetteer of Scotland : a survey of Scottish topography, statistical, biographical and historical. London : W. Mackenzie. p. 91.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Geneanet Family tree of Malcolm MacHeth". Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ↑ The Celtic Review, Vol. 1, No. 3. 1905. pp. 246–260.

- ↑ "Canmore National Record of the Historic Environment". Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- 1 2 Shaw, Lachlan (1775). The History of the Province of Moray.

- ↑ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "William". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 665.

- ↑ Watt, D. E. R.; Murray, A. L., eds. (2003), Fasti Ecclesiae Scotinanae Medii Aevi ad annum 1638, The Scottish Record Society, New Series, Volume 25 (Revised ed.), Edinburgh: The Scottish Record Society, ISBN 0-902054-19-8, ISSN 0143-9448

- ↑ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Alexander II.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 563.

- ↑ Oram, Richard (2002). The Canmores: Kings & Queens of the Scots, 1040-1290. Tempus. ISBN 0752423258.

- ↑ "Receipt by William de Braytoft, knight, castellan of Inverness and Dingwall". National Records of Scotland. 1292. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ↑ "Receipt by William de Braytoft, knight, castellan of Inverness and Dingwall". National Records of Scotland. 1292. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ↑ Bain, J (ed) 1888 Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland, Vol IV. Edinburgh.

- ↑ Prestwich, M. (1997). Edward I. The English Monarchs Series. Yale University Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-300-07209-9. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ↑ Barrow, G. W. S. (1965). Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. London, UK: Eyre and Spottiswoode. pp. 86–8. OCLC 655056131.

- ↑ Barrow, G. W. S. (1965). Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. London, UK: Eyre and Spottiswoode. OCLC 655056131.

- ↑ Barron, E. M (1934). The Scottish War of Independence.

- ↑ Traquair, Peter (2000). Freedom's Sword.

- ↑ Barron, E. M (1934). The Scottish War of Independence.

- ↑ "Tain Museum". 12 January 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ↑ Miller, Hugh (1831). Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Agnes Mure (1934). Robert Bruce, King of Scots.

- ↑ Prestwich, M (1997). The English Monarchs Series. Yale University Press. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07209-9.

- ↑ Crome, Sarah (1999). Scotland's First War of Independence. p. 101.

- ↑ John of Fordun, John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, 311-2

- ↑ Grant, Alexander (2001). Independence and Nationhood — Scotland 1306–1469. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0748602739.

- ↑ "Gift of earldom of Moray with various liberties". Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ↑ Barrell, A. D. M. (2000), Medieval Scotland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-58602-X

- ↑ Anderson, William (1867). The Scottish Nation. pp. 200–1.

- ↑ Armstrong, Pete (2000). The Battle of Dupplin Moor 1332. Lynda Armstong. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Barrell, A. D. M. (2000), Medieval Scotland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-58602-X

- ↑ Spalding Club, Aberdeen (1864). "Publications, Issue 34". p. 71. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ↑ Grant, Alexander (1993). The Wolf of Badenoch. Scottish Society for Northern Studies. ISBN 0-9505994-7-6.

- ↑ Boardman, Stephen (1996). The Early Stewart Kings: Robert II and Robert III, 1371–1406. Birlinn, Limited. ISBN 1-904607-68-3.

- ↑ S. I. Boardman (2004). "Stewart, Robert, first duke of Albany (c.1340–1420)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26502. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Barrow, G W S (1981). The Sources for the History of the Highlands in the Middle Ages. Inverness.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Boardman, Stephen (1996). The Early Stewart Kings: Robert II and Robert III, 1371–1406. Birlinn, Limited. ISBN 1-904607-68-3.

- ↑ Cramond, William (1903). The Records of Elgin, Aberdeen.

- ↑ Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Oram, Richard (2005). The Lordship of the Isles, 1336–1545. pp. 123–39.

- ↑ Brown, Michael (1994), James I, East Linton, Scotland: Tuckwell Press, p. 104, ISBN 978-1-86232-105-2

- ↑ Brown, Michael. James I. pp. 159–60.

- ↑ Oram, Richard. The Lordship of the Isles. p. 134.

- ↑ Macdonald, Angus (1896). The clan Donald. Inverness, The Northern Counties Publishing Company. p. 203.

- ↑ Mahoney, Mike. Scottish Monarchs – Kings and Queens of Scotland – James II.

- ↑ Barrell, A. D. M. (2000), Medieval Scotland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-58602-X

- ↑ Mason, R (2005). Renaissance and Reformation: the sixteenth century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-162243-5.

- ↑ Wormald, J (1991). Court, Kirk and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625. ISBN 0-7486-0276-3.

- ↑ Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 1. 1898. p. 216.

- ↑ Act of 1561, Mary, Queen of Scots

- 1 2 3 Wormald, Jenny (1988). Mary, Queen of Scots. London, England: George Philip. ISBN 978-0-540-01131-5.

- ↑ Weir, Alison (2008) [2003]. Mary, Queen of Scots and the Murder of Lord Darnley. London, England: Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-952707-7.

- ↑ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Murray, James Stuart, Earl of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Guy, John (2004). "My Heart is my Own": The Life of Mary Queen of Scots. London, England: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-84115-753-5.

- ↑ James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray on Undiscovered Scotland, retrieved on 23 January 2020

- ↑ Thomson, David (1998). Nairn in Darkness and Light. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-959990-6.

- ↑ Way, George of Plean; Squire, Romilly of Rubislaw (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. Glasgow: HarperCollins (for the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). pp. 306–307. ISBN 0-00-470547-5.

- ↑ "Inventory Battlefields". Historic Scotland. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011.

- ↑ "Nairn and the Night Attack". Culloden Battlefield and the National Trust of Scotland. April 27, 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ↑ Johnson, Samuel (1775). A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland. Project Gutenberg. p. 11.

- ↑ "Canmore National Record of Historic Environment". Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ↑ "British Newspaper Archive Nairnshire Mirror". Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ↑ "British Newspaper Archive Nairnshire Telegraph". Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ↑ John Thomas, David Turnock (1989). The North of Scotland. St. John Thomas. pp. 225–226. ISBN 9780946537037.

- ↑ Vallance, H.A. (1971). The Highland Railway. p. 18.

- ↑ "Northern Scot Website". Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ↑ "Companies House THE NAIRNSHIRE TELEGRAPH LIMITED". Retrieved 7 May 2022.