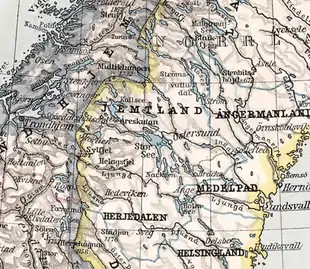

The history of Jämtland dates back thousands of years, starting with the arrival of humans. During the middle ages, Jämtland was an autonomous peasant republic, with its own law, currency and parliament. Jämtland was conquered by Norway in 1178 and stayed Norwegian for over 450 years, maintaining some autonomy until it was ceded to Sweden in 1645. The province has since been Swedish for roughly 350 years, though the population did not gain Swedish citizenship until 1699.

Historically Jämtland was a special territory between Norway and Sweden. During the unrest period in Jämtland's history (1563–1677) it shifted alignment between the two states no less than 13 times. As Jämtland is linked to lands both west and east, particularly to Trøndelag in Norway, it was of great importance for the Jamts to maintain good relationships in both directions.

Prehistory

The first humans came to Jämtland from the west across Kölen approximately 7 000-6 000 BC, after the last ice age. The climate was at the time much warmer than today and trees were growing at the top of today's mountains. The first humans were hunters and gatherers. Several thousand archaeological remains have been located in the province, predominately near old campsites, beaches and lakes. The oldest settlement found was located at Foskvattnet, not far way from the so-called Fosna culture, this settlement has been dated to 6 600 BC. The hunter-gatherers were nomads and constantly followed their prey's movement. In Jämtland the moose was the dominant prey, which is clearly shown on petroglyphs and rock paintings. Jämtland has over 20 000 documented ancient monuments, the oldest one being an 8 000 year old arrowhead found in Offerdal.

Rock paintings found in Jämtland often collocates with various trapping pits and well over 10 000 pits used for hunting have been located, which is much more than any other Scandinavian region. Trapping or hunting pits were placed in areas in close proximity of the hunted animal in question, usually in known places where the animals moved. Because of this there are several places where pits have been dug separately in lines stretching on for miles throughout the landscape. Even today there are several place names in Jämtland that display the significance these pits had to the tribes.

When the climate turned colder again the fauna also changed, the Norway Spruce came to the province 500 BC from the north, and later spread into Norway.

Trapping pit

Trapping pit A moose painted with red ochre near Fångsjön

A moose painted with red ochre near Fångsjön Fångsjön rock art site, dated to 2500-2000 B.C.E

Fångsjön rock art site, dated to 2500-2000 B.C.E Burned rocks in northern Jämtland

Burned rocks in northern Jämtland

A Jamtish Neolithic culture emerged during late Roman Iron Age in Storsjöbygden, though the hunter-gatherers had come in contact with this lifestyle long before they settled down themselves. Though since the hunts were rich and successful in Jämtland it took a long time before a change occurred.

The Neolithic Revolution happened quickly once initiated since the Trønders had been farmers for a long time and some of the Jamts had already begun herding. The Jamtish farmers grew first and foremost barley, though palynological study bear witness of e.g. hemp. At the end of the 4th century a fortress, Mjälleborgen, was established on Frösön in order to control the excessive iron production and trade that took place. The western influence from Trøndelag through Jämtland to Norrland was at the time extensive. At the same time Kurgans starts appearing in the Jämtland landscape, such as Högom in Medelpad. The term Hög was derived from the Old Norse word haugr meaning mound or barrow.

The expansion of settlement was somewhat halted in the 7th century and Mjälleborgen was abandoned in the 8th century. A migration among the people occurred at the same time and the people concentrated themselves around Storsjön with villages such as Frösön, Brunflo, Rödön, Hackås, Lockne and Näs being larger communities. Storsjöbygden became an oasis in the middle of the Scandinavian inland, surrounded by dense forest. Horses were the only reliable mean of communications and a necessity.

Medieval period

During the Viking Age the settlement in the province grew. This may be seen as a confirmation to the sagas written by Snorri Sturluson, where he narrates about the Vikings who fled from Harald Fairhair and Norway and took residence in Jämtland, just like many Norwegians at the same time fled and colonized Iceland. When a climate change (which later resulted in the Medieval Warm Period) took place Frösön acquired the position as regional centre. The warmer climate made the agriculture flourish, the stock-raising and the special inland Scandinavian herding or "livestock drifting", buföring, was developed further. This is especially true for the southern parts of Jämtland when the so-called "fell cow" was introduced. The hunt for moose and other wild animals increased during this period.

Among the worshiped gods in Norse mythology Jämtland was dominated by the older Vanir gods (Freyr, Njord, Ullr etc.). Though the Æsirs were also worshiped. As the population continued to grow the Jamts established an assembly, just like other Germanic tribes. Jamtamót came into existence shortly after the world's oldest parliament, the Icelandic Althing, was instituted in 930 CE. Jamtamót is unique in Scandinavia since it is the only one referred to as mót (a Gothic word) instead of þing, even though they have the same meaning.

Jämtland was Christianized in the middle of the 11th century when the Frösö Runestone was raised (the only one in the world that tells about the christening of a country), shortly after Olaf II of Norway died in the Battle of Stiklestad just west of Jämtland. After this process Jämtland turned into a Christian country and the first church, Västerhus chapel was built shortly after the rune stone was raised.

According to Sturlason's Sagas the Jamts sometimes paid taxes to Norwegian kings such as Håkon Adalsteinsfostre and Øystein Magnusson for protection. The Sagas also mentions that the Jamts at one occasion also paid taxes to a king in Svealand. Though the Sagas reliability on the matter has been defined as low.[2] In the oldest written source for Norway, Historia Norwegiæ, it's however clearly stated that Norway borders in the north-east to Jämtland.

During the civil war era in Norway Jämtland was defeated by king Sverre of Norway after losing the Battle at the ice of Storsjön. This was the last war fought by the Jamts under their own elected leaders. The consequences of this defeat was less autonomy. Though Jämtland never became a fully integrated part of Norway and had the same status in the Norwegian Empire as the Atlantic isles such as Shetland and Orkney, even though Jämtland was connected by land with the rest of Norway. This is clearly shown when Haakon V of Norway refers to Jämtland as his "eastern realm — öystræ rikinu".

Turbulent times

After Norway was forced into a personal union with Denmark (Denmark-Norway) in 1536 Jämtland came to be governed from Copenhagen. Sweden's separation from the Kalmar Union transferred Jämtland from a central Scandinavian region into a border region between two aggressive states. Just like Gotland Jämtland politically belonged to Denmark-Norway and religiously to Sweden. Jämtland had two kings for a while after the introduction of Protestantism (Catholicism survived in some places into the 17th century). This eventually led to conflict, first in 1563 during the Nordic Seven Years' War (after which Jämtland was put under the diocese of Nidaros), then in 1611 during the Kalmar War, when villages were raized and plundered, churches were destroyed, and the population was assaulted. After this incident the Jamts were severely punished by the Danish king, who confiscated much land from the Jamts for having sworn the Swedish king an oath of allegiance, incidentally before the misconducts started. These conflicts continued, Jämtland was occupied yet again in 1644 during the Hannibal War, though the Swedes were quickly driven out by Norwegians and locals. Sweden did, however, win that war in the south and received Jämtland as a part of the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645.

After this Denmark-Norway tried to regain the province, first in the Dano Swedish war of 1657 where the Norwegians were hailed as liberators. Then for a longer period in 1677 with the conquest of Jemtland. The Jamts conducted snapphane activities towards the Swedish army and during this time a Jamt from Lockne, the first known Jamtish poet, wrote a scurrilous song that was sung throughout the province during the war. The last segment of the song was the most derisive one (direct English translation to the right):

|

We have now lived for 30 years time |

The conquest failed and Jämtland was once again in Swedish hands, a Swedification process begun. The Diocese of Härnösand was instituted at the Swedish coast, schools were established (to direct the Jamts away from Trondheim) etc. though the population didn't receive Swedish citizenship until 1699, the Jamts were thus the last people from an acquired territory in Sweden to become Swedish.

The Jamtish people maintained some self-governance. The Jamtamót had been transformed into a Danish landsting in the early 16th century. Even though it was banned in the end of the very same century it continued to be held by the people, in secret. After the transition to Sweden some parts were transmitted into a Swedish landsjämnadsting.

Sweden's intentions in the province were first and foremost focused on defense, which led to an enormous burden for the Jamtish farmers to bear. The Jamts managed to enforce a treaty in 1688 which stated that Jamts were under no circumstances obligated to defend anything but their own province. This treaty was eventually broken by king Charles XII and Jamts participated in Carl Gustaf Armfeldt's 1718 Norwegian campaign during the Great Northern War. The campaign was unsuccessful and when Charles XII died in southern Norway Armfeldt marched back to Jämtland. On New Year's Eve 1718 a massive blizzard arose and over 3 000 Caroleans succumbed in Jämtland's mountains mostly due to poor clothing. The time that followed "the Age of Liberty" brought changes to the province's agriculture, with significances such as the potato and better granaries. The standard of living was greatly improved during this period.

Modern period

In order to end the free trade conducted by "faring-men" or "faring-farmers" (fælmännan or fælbönnran in dialect) Jämtland's first and only city, Östersund, was founded by Gustaf III 1786, though plans had existed since the province was seceded. It took almost one hundred years after this before the province began industrializing when the railroad Mittbanan-Meråkerbanen was established between Sundsvall, Östersund and Trondheim. This evolved the logging process and also led to more people migrating to Jämtland, not to mention all the tourists who came for the "fresh air". In the late 19th century the province was struck by popular movements. In Jämtland the "free minded" Good Templar movement (a part of the temperance movement) came to dominate completely, in fact, the movement drew its strongest support (in relation to the population) in Jämtland in the entire world, and it was also here, in Östersund, that the world's largest order house was built.

References

- Ekerwald, Carl-Göran [in Swedish] (2004). Jämtarnas historia intill 1319. Östersund: Jengel - Förlaget för Jemtlandica.

- Persson, Margareta; Per-Lennart Persson; Bo Oscarsson; Berta Magnusson; Nils Simonsson (1986). Dä glöm fell int Jamska. Offerdal: Margareta Persson.

- Rentzhog, Sten (editor) [in Swedish]; Steinar Imsen; Kerstin Modin; et al. (1995). Jämten 1996. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Rentzhog, Sten (editor); Carl-Göran Ekerwald; Ville Roempke; Frans Järnankar; et al. (1996). Jämten 1997. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Rentzhog, Sten (editor); Hans Westlund; Håkan Larsson; Merete Røskaft; et al. (1999). Jämten 2000. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Rumar, Lars (1998). Historia kring Kölen. Östersund: Jamtli/Jämtlands läns museum.