_-_Auckland.png.webp)

The human history of the Auckland (Tāmaki Makaurau) metropolitan area stretches from early Māori settlers in the 14th century to the first European explorers in the late 18th century, over a short stretch as the official capital of (European-settled) New Zealand in the middle of the 19th century to its current position as the fastest-growing and commercially dominating metropolis of the country.

Māori occupation

Pre-European occupation

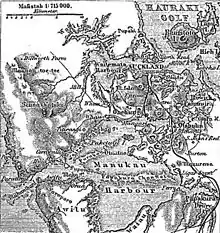

Māori people settled the Auckland isthmus around 1350, calling it Tāmaki or Tāmaki Makaurau, meaning "Tāmaki desired by many", in reference to the desirability of its natural resources and geography.[1] The narrow isthmus was a strategic location with its two harbours providing access to the sea on both the west and east coasts. It had fertile soils that facilitated horticulture and the two harbours provided plentiful kai moana (seafood). Māori constructed terraced pā (fortified villages) on the volcanic peaks. However, for most of the period Māori living in defended pā was a rare event, with most people living in undefended kāinga.[2]

Some of the earliest archaeological sites in Auckland are found on Motutapu Island, Ponui Island, Wattle Bay in the south of the Manukau Heads, and Matukutūruru (Wiri Mountain), however it is likely that early Māori settled widely in the area.[2] From early occupation until European contact, the economy of the region was centred around horticulture (mostly root vegetables such as kūmara (sweet potato)), fishing and shellfish gathering.[2] However, some areas such as Motutapu Island and the Ōtāhuhu/Mount Wellington area had specialised areas to produce toki (stone adze).[3][4][5]

The Ngāi Tai tribe, descended from the people of the Tainui canoe, settled in Maraetai. Other Tainui descendants were Te Kawerau ā Maki, who lived under forest cover in the Waitākere Ranges and controlled land as far north as the Kaipara, across to Mahurangi and down to Takapuna. The Ngāti Te Ata tribe was based south of the Manukau Harbour at Waiuku. Along the coast from Whangaparaoa to the Thames estuary was Ngāti Pāoa, a Hauraki tribe. The dominant power on the Tāmaki isthmus was Waiohua, a federation of tribes formed under Te Hua-o-Kaiwaka.[6]

From 1600 to 1750 the Tāmaki tribes terraced the volcanic cones, building pā. Across the isthmus they developed 2,000 hectares of kūmara (sweet potato) gardens. At the peak of prosperity in 1750, the population numbered tens of thousands. It was pre-European New Zealand's most wealthy and populous area. However, from the early 18th century the Ngāti Pāoa people edged their way into the Hauraki Gulf and as far north as Mahurangi. Between 1740 and 1750 Ngāti Whātua-o-Kaipara moved south, invading the isthmus and killing Kiwi Tāmaki, paramount chief of Waiohua. They then took his last pā at Māngere. Ngāti Whātua secured their dominance of the isthmus by intermarrying with descendants of the Waiohua. There followed a period of cautious peace in which Ngāti Pāoa's conflict with Ngāpuhi tribes in the north made the Tāmaki tribes vulnerable to attack.[6]

Arrival of Europeans

Ngāti Whātua and Tainui tribes were the main groups living in the area when Europeans arrived in New Zealand. European settlement to the north enabled traditional rivals Ngāpuhi and allied northern iwi to acquire muskets by trade. Initially no military advantage accrued; despite lacking muskets, Ngāti Whātua defeated a Ngāpuhi force, who had a few muskets, in the battle of Moremonui north of the Kaipara Harbour (in 1807 or 1808), killing at least 150.[7]

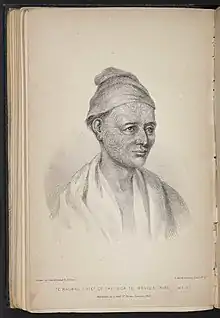

Apihai Te Kawau, leader of the Ngāti Whātua hapu (sub-tribe) Te Taoū, was a good friend of Samuel Marsden. Over a ten-month period in 1821–1822 he played a principal part in the 1,000-mile (1,600 km) Amiowhenua expedition. This series of battles raged through much of the central and southern North Island.[8]

As the Musket Wars drew to a close, pressure for British intervention to quell lawlessness, in large part driven by missionary pressure to protect Māori, led to the annexation of New Zealand and the despatch of Lt Governor Hobson to create the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. (James Cook had claimed New Zealand for Britain under the discovery doctrine, and it was considered by pākehā to be part of New South Wales until 1840.[9])

On 20 March 1840 in the Manukau Harbour area where Ngāti Whātua farmed, now paramount chief Apihai Te Kawau signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the te reo Māori translation of the Treaty of Waitangi).[10] Ngāti Whātua sought British protection from Ngāpuhi as well as a reciprocal relationship with the Crown and the Church. Soon after signing Te Tiriti, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, the primary hapū and landowner in Tāmaki Makaurau, made a tuku (strategic gift) of 3,500 acres (1,400 hectares) of land on the Waitematā Harbour to Hobson, the new Governor of New Zealand, for the new capital.[11][12][13][14][15]

As the Māori population declined for nearly a century, so did the quantity of land held by Ngāti Whātua. Within 20 years, 40% of their lands were lost, some through government land confiscation. At close to the lowest level of population, Ngāti Whātua land holding was reduced to a few acres at Ōrākei, land which Te Kawau had declared "a last stand". By the end of the 1840s, Māori were a minority in the Auckland area. Despite scares during the New Zealand wars, Māori re-emerged as a cultural and political force only after the Bastion Point occupation and Māori cultural revival of the late 20th century.[16][17]

Birth of the city

_p225_AUCKLAND%252C_NEW_ZEALAND.jpg.webp)

Capital of New Zealand

After the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in February 1840 the new Governor of New Zealand, William Hobson, had the task of choosing a capital for the colony. At the time, the main European settlements were in the Bay of Islands and on the Otago Harbour in the South Island. However, the Bay of Islands' geographical position made it very remote, inaccessible and off-centre from the rest of the New Zealand archipelago and Hobson knew little about the South Island and its populations. Auckland was officially declared New Zealand's capital in 1841,[18] and the transfer of the administration from Russell in the Bay of Islands was completed in 1842.

Even in 1840 Port Nicholson (now Wellington Harbour) seemed the obvious choice for an administrative capital. Centrally situated at the south of the North Island, close to the South Island and growing fast, it had a lot to commend it. But the New Zealand Company and the Wakefield brothers had founded and continued to dominate Port Nicholson.

On the initial recommendation of the missionary Henry Williams, supported by the Surveyor General, Felton Mathew, and the offer of land from Ngāti Whātua, Hobson selected the south side of Waitematā Harbour as his future capital, while setting up a temporary capital at Okiato (also known now as Old Russell) in the Bay of Islands. The Chief Magistrate, Captain William Cornwallis Symonds, soon purchased the further land from Ngāti Whātua.

Ngāti Whātua would certainly have expected from British colonialism increased security and trading benefits. This would include greater access via the quickly developed port facilities for the lucrative trade in produce grown in Tainui's fertile Waikato and Hauraki Plains for the Australian prison colonies and Sydney market.

Hobson's barque, the Anna Watson, arrived in Auckland Harbour on 15 September 1840. By coincidence, three days before the Platina had arrived looking for Hobson. This ship carried 130 colonists and a prefabricated Governor's residence, which was similar to the house built to house Napoleon Bonaparte on St Helena during his exile.

A foundation ceremony took place on 18 September 1840, at Point Britomart (Rerenga Ora Iti).[19] Hobson named the new settlement in honour of George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland, a patron and his friend. The New Zealand Government Gazette announced royal approval of the name on 26 November 1842.

From the outset, a steady flow of new arrivals from within New Zealand and from overseas came to the new capital. The first European settlers in Auckland, William Brown and Logan Campbell, had arrived a month earlier on a hunch about Hobson's intentions and bought Browns Island. Soon after Hobson founded Auckland, they built the city's first house, Acacia Cottage, which can still be seen on the side of One Tree Hill, in the park that Campbell donated to the city in his old age.

Initially, settlers from New South Wales predominated. Amongst the first settlers were some Catholics and in 1841 they established a school for boys, which was Auckland's first school of any sort.[20][21][22]

The city's first church, St Paul's and the Fort Britomart army barracks, were built on Point Britomart in 1841. When St Paul's was founded by Governor Hobson on 28 July 1841, hundreds attended the ceremony including Ngāti Whātua chiefs Āpihai Te Kawau, Te Keene and a young Pāora Tūhaere, accompanied by over one hundred Māori warriors. The Bishop of New Zealand, Bishop George Selwyn opened St Paul's in 1843, serving both Māori and European congregations, with two services conducted in te reo Māori and two in English, every Sunday. Known as the 'Mother Church' of Auckland, St Paul's served as the Anglican Cathedral for over 40 years. The original Emily Place St Paul's was demolished in 1885, when Point Britomart was quarried away for waterfront reclamations, and the third and current St Paul's building on Symonds Street was built to replace it.[23][24][25]

The first immigrant ships sailing directly from Britain started to arrive as early as 1842. From early times the eastern side of the settlement remained reserved for government officials while mechanics and artisans, the so-called "unofficial" settlers, congregated on the western side, in areas like Freemans Bay. This social division still persists somewhat in modern Auckland, with the eastern suburbs generally being more upscale.

From the late 1840s, settlers attending Anglican chapels built in the then-rural communities of Tāmaki, Epsom and Remuera were ministered to by the staff and students of St John's Theological College which was established in 1843. Auckland's first Catholic church opened in 1843, later to become St Patrick's Cathedral.[23][26]

Sir George Grey was determined that the capital would not be attacked, as the first capital Russell had been, and so the Royal New Zealand Fencible Corps was formed. Between 1847 and 1852 large numbers of retired British soldiers, called fencibles, and their families came to Auckland to create a ring of outlying villages to protect the capital. Each soldier had to be under 48 and of good character. The fencibles made new villages at Howick, Panmure, Otahuhu and Onehunga. They exercised for 12 days per year and mustered for a church parade, fully equipped in military attire, each Sunday. Anglican clergy were appointed to serve in Onehunga (1847), Howick (1850), and Otahuhu-Panmure (1852). 681 fencibles arrived in 10 ships over 5 years. In addition in 1849 Grey sold land in Māngere to the leading Māori chief Te Wherowhero and 149 members of the Ngāti Mahuta tribe from Tamahere in the Waikato. They were employed on the same basis as the British fencibles. They had British officers but supplied their own arms. In April 1851 a large group of 350–450 Ngāti Pāoa from Thames arrived to attack Auckland in some 20 waka. By the time they landed at Mechanics Bay in Auckland, a British regiment had been called out to defend the city. The Onehunga fencibles were marched to the city as reinforcements and all the other fencible forces were alerted and stood to arms at their villages. HMS Fly went to Mechanics Bay and trained its guns on the Ngāti Pāoa. The reason for the attack was the arrest of a Ngāti Pāoa chief for stealing a shift at a Shortland Street shop. After negotiation, Ngāti Pāoa were given some tobacco and they left. Later they gave Grey a greenstone mere to signal their acceptance of his authority.[27][23]

St Stephen's Anglican School (initially educating Māori girls, then later boys) opened in Kohimarama in 1847 then moved to Parnell in 1850. St Barnabas' chapel was built for Anglican Māori traders, and was sited in Augustus Terrace, Parnell in 1849.[26][28]

St Matthew's was built in 1853 to serve the suburbs of Freemans Bay and Ponsonby; followed by the original St Mary's in Parnell in 1860; then the original St Sepulchre's in 1865, originally a chapel in the Symonds Street Cemetery serving the hospital, prison and later the opulent suburb of Grafton.[26][29]

Auckland was the seat of the New Ulster province from 1846 until its replacement following the passing of the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. The new province, known as Auckland Province, was elected by settlers from 1853 and continued until the abolition of provinces in 1876. The last Lieutenant-Governor of New Ulster, Robert Wynyard, became the first superintendent of Auckland Province following the 1853 New Zealand provincial elections.

Loss of capital status

Eventually in 1865, Port Nicholson, now known as Wellington, became the capital. The advantages of a central position became even more obvious as the South Island grew in prosperity with the discovery of gold in Otago, and with the development of sheep farming and refrigeration, especially refrigerated ships that allowed chilled meat to be safely shipped to Britain. Parliament met for the first time in Wellington in 1862. In 1868 Government House in Wellington became the primary residence of the Governor, although moves to dispense with one in Auckland have never succeeded, in fact for a while the Government maintained a third residence in Christchurch. The return of the Vice-regal household to Auckland was regarded as the start of the Social Season in Auckland and until the turn of the 20th century was marked by a parade from the dockside up Queen Street to Government House.

Aucklanders reacted to the loss of the status of capital by a campaign of redevelopment and rebuilding; including the replacement third Government House, built in 1856 in an attempt to retain the status. The house was in use until 1962, when the fourth Government House was established in Mount Eden.[30] Money was flowing into the city from the goldfields in the Coromandel and resulted in the construction of several public buildings and facilities. Throughout the latter part of the 19th century, Auckland continued to have a major part to play in the cultural landscape of the country. This was largely due to it continuing to be a major port and in particular, the location of the Devonport Naval Base; both the 1902 Royal Tour and especially the 1908 visit by the American Fleet underscored this status. Prior to the opening of the Panama Canal the sea route from Britain was via South Africa and Australia, the opening of the Canal in 1914 altered this and Auckland's port became one of the most important features of the New Zealand economy.

Growth of the city

Auckland formed a base for Governor George Grey's operations against the Māori King Movement in the early 1860s. Grey's modus operandi involved opening up the Waikato and King Country by building roads, most notably Great South Road (a large part of which now forms State Highway 1). This enabled rapid movement, not only of soldiers, but also civilian settlers. It also enabled the extension of Pākehā influence and law to the South Auckland region. Auckland grew fairly rapidly, from 1,500 in 1841 to 12,423 by 1864, with most growth occurring near the port area in Commercial Bay, as well as some small developments towards Onehunga (another port), and at a few favoured spots beside the harbour. During the mid 19th century, European settlement of New Zealand was predominantly in the South Island. Auckland however gradually became the commercial capital. Market gardens were planted on the outskirts, while kauri tree logging and gum digging, mainly by Thomas Henderson, opened up the Waitākere Ranges.

Throughout the 19th century Auckland's intense urban growth concentrated around the port in a very similar manner to most other mercantile cities. At this time Auckland experienced many of the pollution and overcrowding problems that plagued other 19th century cities, although as primarily a port rather than a manufacturing centre it avoided large-scale industrialisation, and by 1900, Auckland was the largest New Zealand city. The overcrowding of the inner city had by then created a strong demand for the city to expand, which was made possible when trams appeared in New Zealand around this time, supported by ferry services, mostly to what would become North Shore City.

A Russian scare at the end of the 19th century had caused coastal guns to be bought and fortifications built, notably at North Head and on Waiheke Island, where they can still be seen.

Twentieth century

New transport and urban sprawl

While trams and railway lines shaped Auckland's rapid extension in the early first half of the 20th century, they were soon overtaken by motor vehicles, with Auckland boasting one of the highest car-ownership rates of the world even before World War II. Their growing popularity meant that urban development was freed from narrow corridors, and could occur anywhere new roads were built, leading to a rapid decentralisation, with urban growth spreading all over the isthmus. In 1959 the new Auckland Harbour Bridge linked North Shore with the city, further extending its reach.

In World War II the city was overflown by a Japanese seaplane, chased ineffectually by a Royal New Zealand Air Force De Havilland Tiger Moth. Again, coastal fortifications were built or extended, with a large military base on Rangitoto Island storing mines supposed to block the inner Hauraki Gulf in the event of an impending Japanese invasion, which never eventuated.

Following the initiative of Michael Joseph Savage's New Zealand Labour Party large numbers of state houses were constructed through the late 1930s, '40s and '50s, usually on quarter-acre (1,000 m²) sections — a tradition that survives despite frequent subdivision. To this day, a large percentage of the houses in Auckland only have one full story. Due to these factors, Auckland is a largely suburban city.

1985 Rainbow Warrior bombing

The Greenpeace flagship craft, the Rainbow Warrior, was docked in the Port of Auckland in July 1985 awaiting departure to lead a flotilla of yachts protesting against French nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago of French Polynesia. Just before midnight NZST on 10 July 1985, two explosive devices attached to the hull by operatives of the French intelligence service (DGSE) were detonated, creating a gaping hole in the side of the vessel. The ship began to sink rapidly, the crew were evacuated but one crew member, Fernando Pereira, drowned on the sinking ship. Two of the French agents were subsequently arrested by the New Zealand Police and pled guilty to manslaughter.

Problems in infrastructure

In 1993, the Police Eagle helicopter and a traffic-spotting plane collided in mid-air, falling to the packed motorway below during Friday night rush hour. Four people died and traffic became grid-locked over much of the inner city.[31]

All four electrical power cables supplying the Central Business District failed on 20 February 1998, causing the 1998 Auckland power crisis. It took five weeks before an emergency overhead cable was completed to restore the power supply to the Central Business District. For much of that time, about 60,000 of the 74,000 people who worked in the area worked from home or from relocated offices in the suburbs. Many of the 6,000 apartment dwellers in the area had to find alternative accommodation. Mercury Energy, operators of the cable that failed, had to spend many millions of dollars on the temporary cable, and compensation for local businesses.

The 2006 Auckland Blackout showcased the fact that Auckland's power-supply infrastructure is still very vulnerable to disruption. A faulty powerline shackle caused a short-circuit at the Otahuhu substation, with the blackout affecting wide parts of the conurbation, including the CBD, but sparing most of Waitakere City and North Shore City. While the blackout lasted only about half a day, it reignited political pressure aiming to improve the national electricity grid.

See also

References

- ↑ "About Auckland". The Auckland Plan 2050. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 Davidson, Janet M. (1978). "Auckland Prehistory: A Review". Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum. 15: 1–14. ISSN 0067-0464.

- ↑ Foster, Russell; Sewell, Brenda (1989). "THE EXCAVATION OF SITES R11/887, R11/888 AND R11/899, TAMAKI, AUCKLAND". Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum. 26: 1–24. ISSN 0067-0464.

- ↑ Furey, Louise (1986). "THE EXCAVATION OF WESTFIELD (R11/898), SOUTH AUCKLAND". Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum. 23: 1–24. ISSN 0067-0464.

- ↑ Davidson, Janet; Leach, Foss (2017). "Archaeological excavations at Pig Bay (N38/21, R10/22), Motutapu Island, Auckland, New Zealand, in 1958 and 1959". Records of the Auckland Museum. 52: 9–38. doi:10.32912/ram.2017.52.2.

- 1 2 McClure, Margaret (5 August 2016). "Auckland region - Māori history". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ↑ Smith, S. Percy (1910). "Moremo-nui, 1807". Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century. Whitcombe and Tombs Limited (republished in New Zealand Electronic Text Collection). p. 47. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ↑ Pihema, Ani; Kerei, Ruby; Oliver, Steven. "Apihai Te Kawau". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ↑ See History of New Zealand.

- ↑ "Āpihai Te Kawau". New Zealand History. NZ Government. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ↑ "Apihai Te Kawau". Ngāti Whātua-o-Ōrākei. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ↑ "Cultural Values Assessment in Support of the Notices of Requirement for the Proposed City Rail Link Project" (PDF). Auckland Transport. pp. 14–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ↑ "Tāmaki Herenga Waka: Stories of Auckland". Flickr. Auckland Museum. 18 April 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ↑ Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Trust (2 June 2021). "Statement of evidence of Ngarimu Alan Huiroa Blair on behalf of the plaintiff" (PDF). ngatiwhatuaorakei.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ "Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Deed of Settlement" (PDF). govt.nz. 5 November 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ Ngati Whatua Archived 6 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine (from Te Ara: The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 1966)

- ↑ Ngāti Whātua history Archived 6 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine (from the Auckland City Council website)

- ↑ Stone, Russell (2001). From Tamaki-Makau-Rau to Auckland. University of Auckland Press. ISBN 1-86940-259-6.

- ↑ "New memorial marks founding of Auckland". RNZ. 4 May 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ A. G Butchers, Young New Zealand, Coulls Somerville Wilkie Ltd, Dunedin, 1929, pp. 124 – 126.

- ↑ Auckland's First Catholic School – And its Latest", Zealandia, Thursday, 26 January 1939, p. 5

- ↑ E.R. Simmons, In Cruce Salus, A History of the Diocese of Auckland 1848 – 1980, Catholic Publication Centre, Auckland 1982, pp. 53 and 54.

- 1 2 3 "Auckland region – The founding of Auckland: 1840–1869". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ↑ "St Paul's Church (Anglican)". New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ↑ Hawkins, Simeon. "King, Bishop, Knight, Pioneer: the Social and Architectural Significance of Old St Paul's Church, Emily Place, Auckland. 1841-1885" (PDF). The University of Auckland. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 "History of the Diocese of Auckland". Anglican Diocese of Auckland. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ The Royal New Zealand Fencibles 1847–1852.R. Alexander. G Gibson. A. LaRoche. Deed. Waiuku .1997.pp717,108,64,71,80,110

- ↑ "History of St Barnabas". St Barnabas Anglican Church. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ "Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Hall". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ↑ "Other Government Houses". Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Our History – Responses". Auckland Operational Support.

Further reading

- "Auckland City", Brett's New Zealand and South Pacific Pilot, Auckland, N.Z: Printed by H. Brett, 1880, OL 7152786M

- "Auckland", New Zealand Handbook (14th ed.), London: E. Stanford, 1879

- "Auckland", Pictorial New Zealand, London: Cassell and Co., 1895, OCLC 8587586, OL 7088023M

- "Auckland", New Zealand as a Tourist and Health Resort, Auckland: T. Cook & Son, 1902, OCLC 18158487, OL 7093583M

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 894.

- C. N. Baeyertz (1912), "Auckland", Guide to New Zealand, Wellington: New Zealand Times Co., OCLC 5747830, OL 251804M

- John Barr (1922), The city of Auckland, New Zealand, 1840–1920, Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs, OL 24364862M

External links

- History and Heritage – Heart of the City

![]() Media related to History of Auckland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Auckland at Wikimedia Commons