Hebron Church | |

Main façade (northwestern elevation) of Hebron Church, 2015 | |

Hebron Church  Hebron Church  Hebron Church | |

| Location | 10851 Carpers Pike (West Virginia Route 259) Intermont, West Virginia, United States[1] |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°09′03″N 78°32′30″W / 39.15083°N 78.54167°W |

| Area | 3.879 acres (1.570 ha) |

| Built | 1849, 1905 |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 14001057[2] |

| Designated | December 16, 2014 |

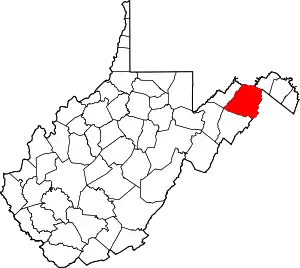

Hebron Church (also historically known as Great Capon Church, Hebron Lutheran Church, and Hebron Evangelical Lutheran Church) is a mid-19th-century Lutheran church in Intermont, Hampshire County, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. Hebron Church was founded in 1786 by German settlers in the Cacapon River Valley, making it the first Lutheran church west of the Shenandoah Valley. The congregation worshiped in a log church, which initially served both Lutheran and Reformed denominations. Its congregation was originally German-speaking; the church's documents and religious services were in German until 1821, when records and sermons transitioned to English.

The church's congregation built the present Greek Revival-style 1+1⁄2-story church building in 1849, when it was renamed Hebron on the Cacapon. The original log church was moved across the road and subsequently used as a sexton's house, Sunday school classroom, and public schoolhouse (attended by future West Virginia governor Herman G. Kump).

To celebrate the congregation's 175th anniversary in 1961, Hebron Church constructed a brick community and religious education building designed to be architecturally compatible with the 1849 brick church. As of October 2015, the church continues to be used by the West Virginia-Western Maryland Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Hebron Church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 16, 2014, for its architectural distinction as a local example of vernacular Greek Revival church architecture in the Potomac Highlands.

Geography and setting

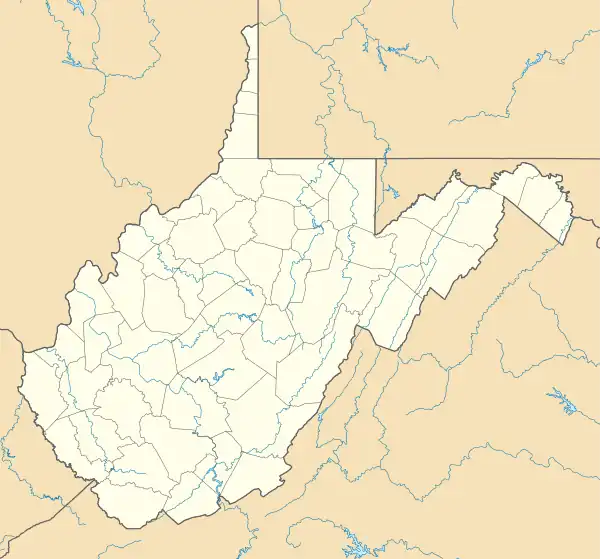

Hebron Church and its cemetery are located east of Carpers Pike (West Virginia Route 259) in the unincorporated community of Intermont, about 3.20 miles (5.15 km) southwest of Yellow Spring, and 5.63 miles (9.06 km) northeast of the town of Wardensville.[3] Capon Lake and the Capon Lake Whipple Truss Bridge are 0.64 miles (1.03 km) northeast of the church.[3][4] The church and its cemetery are on a 3.879-acre (1.570 ha) lot.[5]

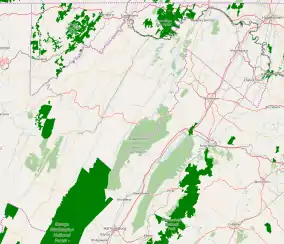

Hebron Church is on the plain of a predominantly rural agricultural and forested area of southeastern Hampshire County, in the Cacapon River Valley.[3][6] Baker Mountain, a forested, narrow anticlinal mountain ridge, rises west of the church, and the western rolling foothills of the anticlinal Great North Mountain rise east of the valley.[3] The Cacapon River, just southeast of the church, is hidden from the church and cemetery by mature foliage.[3][6] George Washington National Forest, encompassing the forested area east of the Cacapon River, is east of the church.[3]

The National Register of Historic Places listing for Hebron Church includes the brick church and cemetery. They are accessible from WV 259 by a semicircular asphalt driveway, separated from the church and cemetery by a wrought iron fence and lined with large, old-growth maple trees along the property's northwestern perimeter. A paved brick walkway leads from the gate to the northwestern façade and two main entrances of the church. The church is surrounded on its northeastern, southeastern, and southwestern sides by a cemetery which is still in use. The cemetery contains over 600 gravestones, several yuccas, a hemlock tree, and a boxwood. A modern brick community building, within the historic boundary south of the church and cemetery, is used for church activities.[6]

History

Background

The land upon which Hebron Church and its cemetery are located was originally part of the Northern Neck Proprietary, a land grant that the exiled Charles II awarded to seven of his supporters in 1649 during the English Interregnum.[7][8][9] Following the Restoration in 1660, Charles II finally ascended to the English throne.[10] Charles II renewed the Northern Neck Proprietary grant in 1662, revised it in 1669, and again renewed the original grant favoring original grantee Thomas Colepeper, 2nd Baron Colepeper and Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington in 1672.[11] In 1681, Bennet sold his share to Lord Colepeper, and Lord Colepeper received a new charter for the entire land grant from James II in 1688.[7][12][13] Following the deaths of Lord Colepeper, his wife Margaret, and his daughter Katherine, the Northern Neck Proprietary passed to Katherine's son Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron in 1719.[7][14][15]

Under Lord Fairfax's ownership, the Cacapon River Valley was predominantly inhabited by English-speaking settlers as early as the late 1730s; most came from Pennsylvania and New Jersey.[16][17] As settlement progressed during the second half of the 18th century, the fertile land of Hampshire County (including the Cacapon River Valley) also attracted German settlers from Pennsylvania and elsewhere in Virginia before and after the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783).[17][18]

Establishment

As the population of German settlers in the region began to increase, the desire for Lutheran religious services and education also grew. Ministers, including Henry Muhlenberg disciple Christian Streit, began to establish congregations in the largest communities of western Virginia.[18] Muhlenberg was a German pastor, requested by colonists in Pennsylvania, who served as a missionary there from 1742 until his death in 1787;[19] he is considered the patriarch of the Lutheran Church in the United States.[18] Johannes Schwarback and Muhlenberg's son, Peter, reportedly visited the Cacapon River Valley between 1763 and 1776 (before Hebron Church's founding).[20] Streit, charged with ministering to a Lutheran congregation in Winchester, settled there on July 19, 1785.[18][21][22]

Hebron Church, originally known as the Great Capon Church, was established by early German settlers in 1786 as a united German congregation of the Reformed and Lutheran denominations.[23][24][25] The congregation was also known as the German Churches, since it served both denominations. In its earliest days, the church was served by pastors connected with congregations in the Shenandoah Valley.[26] Streit incorporated the church into his circuit shortly after its founding, regularly traveling to the Cacapon River Valley for baptisms and weddings, but his ministry did not extend west of Cooper Mountain.[17][24] According to the oldest extant church record, six people were confirmed in the Lutheran Synod and nine confirmed in the German Reformed Church in November 1786. On September 23, 1787, seven more people were confirmed in the Lutheran Synod; the church's enrollment then began to increase.[23]

Early religious services were held in the log church[23][26] on land deeded to Reformed trustee Jacob Huber and Lutheran trustee John Nicholas Schweitzer, both of whom were church elders in 1786.[24][25] The deed conveying the land to the trustees specified that it was to be used for a German church and burial yard.[24] The united congregation became Hebron Church, the first Lutheran church west of the Shenandoah Valley.[24]

While the Reformed and Lutheran congregations used the log church, they were ministered by two pastors. Abraham Gottlieb Deschler ministered to the Lutherans, and Jacob Rebas (or Repass) ministered to the Reformed congregation until the latter dissolved around 1813.[24] Although the church served both denominations, it was later served by one minister (Reformed or Lutheran).[26] Originally a German-speaking congregation, its documents and religious services were in German until 1821 (an early transition to English for a German denomination in the United States).[17][24][25] By that time, under the pastorship of Abraham Reck (1812–21), the congregation was known as Capon Church.[26]

Construction

The congregation of Great Capon Church built the present 1+1⁄2-story Lutheran church building in 1849, when it was briefly renamed Hebron on the Cacapon after the Scriptural Hebron (the city associated with Judah, Abraham, and Isaac).[23][24][27] The church was later known simply as Hebron Church.[24][27]

The brick church was constructed east of the original log structure, which was located to the west of the present community building. The 1849 church was originally topped by a wooden shake roof, and its windows had double-hung wooden sashes. Its pews were built by Alfred Brill, Jacob Himmelwright and Frederick Secrist with lumber milled by Brill.[24] The church was constructed under the ministry of H. J. Richardson (1848–53).[26]

The log church was moved from its original location in the south corner of the cemetery to a hill across the road from the brick church.[23] It was used as a sexton's house for the church, and was a Sunday school classroom for about 30 years.[23][24][26] In addition to religious instruction, the log building was a public schoolhouse.[23][24] Future West Virginia governor Herman G. Kump and his brother, the judge Garnett Kerr Kump, received part of their primary education in the schoolhouse.[23] By 1885, a Mr. Miller was teaching business principles at the school.[24] The log building succumbed to the elements, and no longer exists.[23]

Later history

Peter Miller ministered to the congregation at Hebron Church four times, for a total of 25 years, between 1858 and 1918.[28] Licensed in 1858 and ordained in 1860, Miller engaged in missionary work for rural congregants in the Capon and North River Parish of Hampshire and Hardy counties for 60 years.[28][29] He established many of the area's Lutheran churches and, according to the North Carolina Synod of the Lutheran Church in America, was "an outstanding figure in this large, mountainous, thinly populated territory, who for sixty years almost continuously was recognized as everybody's pastor".[28][29] By 1867, the church membership was 106, its largest congregation to date.[26]

On October 13, 1879, a post office was established near Hebron Church to serve the adjacent community (then known as Mutton Run).[30] In December 1884, the church roof caught fire from an adjacent flue, burning a hole through the sanctuary's ceiling which was soon repaired.[31] On August 11–15, 1886, Hebron Church celebrated its centennial.[26][32] During the celebration, Miller read a complete history of the German churches in the region.[28] The centennial was reportedly the first of any Lutheran congregation in the southern United States.[20]

The wrought-iron fence along the church driveway was installed in April 1895, replacing a picket fence.[6] In 1905, the church's wood roof was replaced with a metal one, the present stained-glass windows were installed, its interior and woodwork were painted, and new lamps were installed for better illumination.[31] The stained-glass windows were supplied by Madison Alling of Newark, New Jersey in memory of his father, who summered at nearby Capon Springs Resort.[31] Alling also provided four hanging lamps and calcimine for the interior walls and paint for the interior woodwork.[31] Anton Reymann of Wheeling, West Virginia funded the metal roof and the sanctuary's painting and decoration.[31]

On June 11, 1915, the post office changed its name to Intermont (after the Intermountain Construction Company), operating until its closure on January 29, 1972.[30] The unincorporated community around Hebron Church continues to be known as Intermont, after the former post office.[30] By 1921, the Winchester and Western Railroad had been constructed to the east of Hebron Church by the Intermountain Construction Company to connect Wardensville with Winchester and develop the area's timber, mining, and fruit industries.[30][33][34]

In 1932, the church's piano was donated by George E. Brill of Baltimore.[31] Hebron Church celebrated its 150th anniversary in 1936, during the pastorate of Lawrence P. Williamson (1930–37).[20] On October 29, 1961, in celebration of the church's 175th anniversary, the congregation dedicated a new brick community and religious-education building designed to be architecturally compatible with the 1849 brick church.[23][25][35] The new building, which hosted community gatherings, events and Sunday school,[31] was built just south of the brick church at the edge of the cemetery (where the old log church was originally located).[23] Walter A. Sigman (1960–65) was pastor when the community building was dedicated.[20]

Preservation

In 2008, a survey of historic properties in the county was undertaken by the State Historic Preservation Office of the West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Following this survey, the Hampshire County Historic Landmarks Commission and the Hampshire County Commission began an initiative to place these identified structures and districts on the National Register of Historic Places.[36] Preparation of the necessary documentation for Hebron Church, French's Mill, Yellow Spring Mill, and the Nathaniel and Isaac Kuykendall House began in April 2013, when Governor Earl Ray Tomblin awarded $10,500 to the Hampshire County Commission.[37] The cost of the commission's documentation of the history and significance of the four properties was $15,000, of which the county paid $4,500.[37]

All four properties were accepted for the NRHP on December 16, 2014,[2][38] with Hebron Church a unique local example of Greek Revival church architecture in the Potomac Highlands.[18] Because the church's original architectural design, workmanship, and building materials are extant, architectural historian Sandra Scaffidi assessed the church as providing "insight into the construction techniques of a mid-19th-century ecclesiastical building".[18] Hebron Church is one of six extant, rural pre-Civil War church buildings in Hampshire County; the other five are Bloomery Presbyterian Church (1825), Mount Bethel Church (1837), Old Pine Church (1838), Capon Chapel (c. 1852), and North River Mills United Methodist Church (1860).[39]

As of October 2015, the church's congregation is part of the Potomac Conference in the West Virginia-Western Maryland Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Ministered by David A. Twedt, Hebron Church has 22 baptized members, 19 confirmed members and an average attendance of six.[40][41]

Pastors

Since the church's founding in 1786, the following pastors have ministered to the congregation at Hebron Church:[42]

- Abraham Gottleib Deschler (1786)

- Jacob Rebas (or Repass) (1786) †[24]

- John Lotroizer (1793) †

- Carl A. Keirst (1797)

- William Forster (1799–1805)

- M. Willey (1802) †

- Paul Henkel (1808–09)

- Christian Streit (1809–11)

- M. Franke (1811)

- G. W. Schneider (1812)

- Abraham Reck (1812–21)[26]

- W. G. Keil (1822–27)

- L. Eichelberger (1829–38)

- I. Baker (1839)

- W. Shepperson (1841–42)

- J. T. Tabler (1843)

- J. Richard (1845–46)

- H. J. Richardson (1848–53)[26]

- William Rusmissel (1853–57)

- Peter Miller (1858–71)

- Webster Eichelberger (1871–77)

- L. M. Sibole (1878–83)

- Peter Miller (1884–90)

- P. J. Wade (1890–95)

- D. W. Michael (1895–98)

- W. H. Riser (1898–99)

- Peter Miller (1898–1900)

- J. K. Efred (1899–1901)

- C. M. Fox (1902–05)

- M. L. Camp (1905)

- P. J. Wade (1905–08)

- A. M. Smith (1908–09)

- C. W. Hepner (1910)

- H. E. H. Sloop (1911–15)

- Peter Miller (1915–18)

- P. L. Miller (1918–19)

- D. W. Files (1919–23)

- George W. Stroudemeyer (1927–30)

- Lawrence P. Williamson (1930–37)

- Martin Luther Zirkle (1938–42)

- Herbert P. Stelling (1943–44 and 1947–48)

- Charles A. Stroh (1949)

- Gordon K. Zirkle (1950–59)

- Walter A. Sigman (1960–65)

- Martin T. Young (1967–69)

- Elmer Ganskopp (1970–76)

- David A. Twedt (current as of October 2015)[40]

- † Reformed pastors; the remaining pastors were Lutheran.[42]

Architecture

According to Sandra Scaffidi, Hebron Church's architecture exemplifies a "local interpretation" of the Greek Revival architectural style, which was popular at the time of its construction. With its simple wooden doors, returning eaves and symmetrical front-gable design, Hebron Church is representative of a vernacular interpretation of Greek Revival architecture. Only one other church building in eastern Hampshire County, Timber Ridge Christian Church in High View, was built of brick.[35] The overall plan of Hebron Church exemplifies traditional Lutheranism, with the sanctuary's one-room floor plan enabling the congregation to be near its minister and easily participate in worship.[39] Scaffidi wrote, "The Greek Revival front-gable form of the Hebron Church reflects the early settlers' desire to worship in a modest, uncluttered fashion."[43]

Exterior

The 1849 church is a small, 1+1⁄2-story, front-gable building.[6][44] The main façade (northwestern elevation) has two main entrances, enclosed by white-painted wood, recessed panel doors, and capped by white-painted stone lintels with two stone corner blocks. The church's exterior is brickwork, laid in Flemish bond on the main façade and a five-course American bond on the northeastern, southeastern and southwestern elevations.[6] Two blue-gray stained glass windows (installed in 1905) are symmetrically placed above the main entrances, each capped by stone lintels with two stone corner blocks. The main façade is crowned by a white painted entablature molding with two cornice returns, exemplifying Greek Revival architectural design. In the top of the gable, a square date stone engraved "1849" is embedded in the brickwork above a gooseneck light fixture.[45] Although the church is now topped by a metal standing-seam roof, it was originally sheathed by wooden shakes.[6]

On the church's northeastern elevation there are three large, symmetrical stained-glass windows, each with a fixed upper sash and a lower hopper sash. Like the main façade's doorways and windows, the sills, lintels and lintel corner blocks of the stained-glass windows are white-painted stone. Below the windows is an exposed coursed-stone foundation with five tie-rod masonry anchor plates. A small brick chimney is present on this elevation. The church's southwestern elevation also has a coursed-stone foundation, with five tie-rod anchor plates, banked into the ground below three symmetrical stained-glass windows with fixed upper sashes and lower hopper sashes and encased with white-painted stone sills, lintels and lintel corner blocks. On this elevation are a small brick chimney in the roof slope and metal snowbirds along the roof line. Downspouts are located at the southern corners of the northeastern and southwestern elevations. The church's southeastern (rear) elevation has an exposed coursed-stone foundation 4 feet (1.2 m) high, due to its location on sloping ground. At the center of this elevation is a protruding, gabled brick extension for the interior altar, with symmetrical stained-glass windows on both sides. The gabled protrusion is capped by aluminum flashing.[45] An 1895 wrought-iron fence encloses the property's northwestern perimeter, and a paved brick walkway provides pedestrian access from the driveway to the two main entrances.[6]

Interior

The church interior has an open floor plan, with a sanctuary measuring 28 feet (8.5 m) wide and 43 feet (13 m) long. The floor plan is an open nave, with two aisles partitioning three sections of rectangular wooden pews. Although the pews had been painted white, they have been restored to their original wood finish. The sanctuary's interior walls are plaster, and the floors are sheathed in wide wooden planks. The nave is topped by a ceiling fabricated on tongue and groove wooden planks painted white. Three large stained-glass windows, framed by wooden molding and recessed approximately 6 inches (15 cm), are symmetrically located on the northeastern and southwestern walls. The lower portion of each window contains a memorial dedication, which opens into its lower hopper sash. On the northwestern side of the interior are the two main entry doors, which access an unadorned narthex. Two tapered-square pilasters support an upper gallery loft, possibly used by slaves during religious services. The gallery is fronted by a solid balustrade, accented with dentil molding and recessed wooden panels.[45]

At the southeastern end of the sanctuary, the altar is atop a decagonal platform about 8 feet (2.4 m) above the floor and accessible by a pair of four-step staircases. On the elevated platform is also a table holding a Bible. A recessed rectangular apse, flanked by a pair of fluted, engaged columns, is behind the altar. A painting of Jesus hangs in the center of the apse, with an American flag to its immediate north. An organ and a piano are north of the altar, with a baptismal font south of it. The altar platform and aisles are carpeted red. The sanctuary's northern and southern elevations exposed brick chimneys connected to gas heating units, which were installed around 1970. A brass chandelier with clear glass hurricane globes is suspended in the center of the sanctuary; on the northern and southern elevations, two brass electric lanterns are adjacent to the stained-glass windows.[31]

The upper gallery on the northwestern side of the church is accessed by a twelve-step wooden spiral staircase, and has an unfinished wooden floor. Four wooden pews have white-painted sides and unfinished seats and rails. The gallery's ceiling height is about 6 feet (1.8 m) at its tallest and about 5 feet (1.5 m) at its shortest, due to the sloping wooden floor. Two stained-glass windows, which cannot be opened, are along the northwest wall. A small closet, accessible through a wooden door with two parallel vertical panels and original latch hardware, is at the base of the staircase. The church's original plasterwork and a 10-inch (25 cm) vertically cut wooden board, suggesting half-timbering, are visible in the closet.[31]

Community building

The church's community building, a non-contributing structure within the historic boundary, is southwest of the church. The building is a venue for Sunday school classes and community gatherings. The front-gable building, completed in 1961, is sheathed in brickwork. Similar to the church, the building is built into a gently sloping bank with its one-story elevation at grade facing west toward WV 259.[31] Its two-story eastern elevation is at the foot of the hillside.[46]

The building's western façade has a central entryway with double doors, topped by a six-light transom and flanked by engaged pilasters. Its gable, sheathed in aluminum siding, incorporates a gabled pediment and the building's perimeter is surrounded by a wide, flat frieze. The building's southern elevation has wooden windows with 12-over-12 double-hung sashes on brick window sills. Its basement level has one entrance, flanked by wooden double-hung sash windows and four casement windows. The northeastern elevation has three stained-glass windows on the main level, with three wooden eight-over-eight double-hung sash windows; a single wooden six-over-six double-hung sash window is in the gable. The building is roofed with asphalt shingles, and a brick chimney is along the slope of the northern elevation's roof line. Its northeastern elevation has five wooden 16-over-16 double-hung sash windows on the main level and four on the lower level, in addition to two wooden four-over-four sash windows.[46]

Graveyard

Hebron Church is surrounded on three sides by a graveyard, consisting of about 700 granite, marble, slate and wooden headstones laid in semi-regular rows running northeast to southeast.[6][46] The graveyard also abuts the northeastern elevation of the community building. Its interments date from about 1806 to the present; early headstones have deteriorated beyond recognition, and may be older than 1806. Slaves and other people of color are interred in a small area of the graveyard's southeastern section, with simpler markers than the cemetery's other headstones. Although its headstones are generally rectangular granite stones and large obelisks, the graveyard's earliest headstones were simple wooden boards. Several gravestones are ornately carved, including one modeled on a tree stump. The graveyard is active, with the most recent burials at the property's northern end.[46] Dr. William Blum Sr., an electrochemist at the National Bureau of Standards who invented a chrome plating technique used in banknote printing, is interred at the cemetery.[47][48][49]

See also

References

- ↑ Scaffidi 2014, p. 1 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 "Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 12/15/14 through 12/19/14". National Park Service. December 24, 2014. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yellow Spring Quadrangle–West Virginia (Topographic map). 1 : 24,000. 7.5 Minute Series. United States Geological Survey. 1970. OCLC 36574404.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Capon Lake

- ↑ Scaffidi 2014, p. 4 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Scaffidi 2014, p. 5 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 Munske & Kerns 2004, p. 9.

- ↑ Coleman 1951, p. 246.

- ↑ Rose 1976, p. 25.

- ↑ William and Mary Quarterly 1898, p. 222.

- ↑ William and Mary Quarterly 1898, pp. 222–23.

- ↑ Brannon 1976, p. 286.

- ↑ William and Mary Quarterly 1898, p. 224.

- ↑ William and Mary Quarterly 1898, pp. 224–26.

- ↑ Rice 2015, p. 23.

- ↑ Munske & Kerns 2004, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Munske & Kerns 2004, p. 101.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scaffidi 2014, p. 9 of the PDF file.

- ↑ von Auenmueller 2012, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 3 4 Brannon 1976, p. 478.

- ↑ Munske & Kerns 2004, p. 102.

- ↑ Cartmell 2009, p. 192.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Brannon 1976, p. 477.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Scaffidi 2014, p. 10 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 4 Eisenberg 1967, p. 463.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Maxwell & Swisher 1897, p. 375.

- 1 2 Eisenberg 1967, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 Brannon 1976, p. 479.

- 1 2 Lutheran Church in America, North Carolina Synod 1966, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 4 McMaster 2010, p. 39 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Scaffidi 2014, p. 7 of the PDF file.

- ↑ Brannon 1976, pp. 477–78.

- ↑ "Into Virginia Territory, New Railway From Winchester That Will Develop Timber, Mining, and Fruit-Growing Lands". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. September 2, 1917. p. 12. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Chronicling America.

- ↑ "Expect Motor Trucks to Revolutionize Traffic: Look for Gasoline-Propelled Devices to Prove Their Efficiency on Short-Line Railroads". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. March 20, 1921. p. 3. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015 – via Chronicling America.

- 1 2 Scaffidi 2014, p. 11 of the PDF file.

- ↑ Pisciotta, Marla (May 11, 2011). "Preserving Our History". Hampshire Review. Romney, West Virginia. p. 1B.

- 1 2 Pisciotta, Marla (December 5, 2014). "Seven W.Va. locations nominated for National Register of Historic Places". Cumberland Times-News. Cumberland, Maryland. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ↑ Review Staff (December 31, 2014). "4 sites make historic register". Hampshire Review. Romney, West Virginia. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- 1 2 Scaffidi 2014, p. 12 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 "Hebron Lutheran Church". Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "West Virginia-Western Maryland Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America – Twenty-Seventh Annual Assembly" (PDF). West Virginia-Western Maryland Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 2014. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- 1 2 Brannon 1976, pp. 478–79.

- ↑ Scaffidi 2014, p. 13 of the PDF file.

- ↑ Scaffidi 2014, p. 2 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 Scaffidi 2014, p. 6 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 4 Scaffidi 2014, p. 8 of the PDF file.

- ↑ "Dr. William Blum Sr". Winchester Evening Star. Winchester, Virginia. December 8, 1972. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Service for Dr. Wm. Blum, Electrochemist". Winchester Evening Star. Winchester, Virginia. December 12, 1972. p. 2. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hebron Lutheran Cemetery 1786, Intermont, WV". HistoricHampshire.org. HistoricHampshire.org, Charles C. Hall. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

Bibliography

- Brannon, Selden W., ed. (1976). Historic Hampshire: A Symposium of Hampshire County and Its People, Past and Present. Parsons, West Virginia: McClain Printing Company. ISBN 978-0-87012-236-1. OCLC 3121468.

- Cartmell, T. K. (2009). Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants: A History of Frederick County, Virginia from Its Formation in 1738 to 1908. Bowie, Maryland: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-1-55613-243-8. OCLC 20963384. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Coleman, Roy V. (1951). Liberty and Property. New York City: Scribner. OCLC 1020487 – via Internet Archive.

- Eisenberg, William Edward (1967). The Lutheran Church in Virginia, 1717–1962: Including an Account of the Lutheran Church in East Tennessee. Roanoke, Virginia: Trustees of the Virginia Synod, Lutheran Church in America. OCLC 4790884. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2015 – via Google Books.

- Lutheran Church in America, North Carolina Synod (1966). Life Sketches of Lutheran Ministers: North Carolina and Tennessee Synods, 1773–1965. Columbia, South Carolina: Lutheran Church in America, North Carolina Synod. OCLC 3634112 – via Internet Archive.

- Maxwell, Hu; Swisher, Howard Llewellyn (1897). History of Hampshire County, West Virginia From Its Earliest Settlement to the Present. Morgantown, West Virginia: A. Brown Boughner, Printer. OCLC 680931891. OL 23304577M.

- McMaster, Len (2010). Hampshire County West Virginia Post Offices, Part 2 (PDF). LaPosta: A Journal of American Postal History. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- Munske, Roberta R.; Kerns, Wilmer L., eds. (2004). Hampshire County, West Virginia, 1754–2004. Romney, West Virginia: The Hampshire County 250th Anniversary Committee. ISBN 978-0-9715738-2-6. OCLC 55983178.

- Rice, Otis K. (2015). The Allegheny Frontier: West Virginia Beginnings, 1730–1830. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-6438-0. OCLC 900345296. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Rose, Cornelia Bruère (1976). Arlington County, Virginia: A History. Arlington County, Virginia: Arlington Historical Society. OCLC 2401541. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016 – via Google Books.

- Scaffidi, Sandra (July 28, 2014). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Hebron Church (PDF). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- von Auenmueller, Hardy (2012). "Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (1711–1787)" (PDF). German Society of Pennsylvania website. German Society of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- William and Mary Quarterly (April 1898). "The Northern Neck of Virginia". William and Mary Quarterly. 6 (4): 222–26. doi:10.2307/1915885. ISSN 0043-5597. JSTOR 1915885. OCLC 1607858.

External links

- Hebron Church Cemetery: Inventory of Interments

Media related to Old Hebron Lutheran Church (Intermont, West Virginia) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Old Hebron Lutheran Church (Intermont, West Virginia) at Wikimedia Commons- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hebron Church

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hebron Lutheran Church Cemetery

- Hebron Church at Find a Grave