| Hashish and Wine | |

|---|---|

| by Fuzuli | |

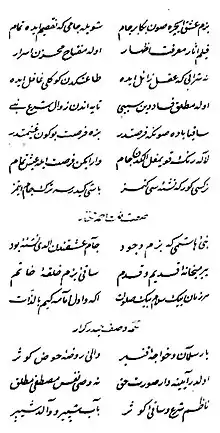

Manuscript from Austria (1830) Azerbaijan National Library | |

| Original title | (Azerbaijani: Bəngü-Badə) |

| Written | 1510-1524 |

| Language | Azerbaijani |

| Genre(s) | poem-munazara |

| Full text | |

"Hashish and Wine",[1][2][3][4] also known as "Opium and Wine",[5] "Bangu Bada" ("Bengu Bada"[2] or "Bang va bada"[3] Azerbaijani: Bəngü-Badə) or "Bang u Bada Munazarasi" ("The dispute of Hashish with the Wine")[6] - is an allegorical-satirical poem,[4] written by Fuzuli in the Azerbaijani language.[7][8] The poem is dedicated to Shah Ismail I.[9]

History of creation

.JPG.webp)

After the ruler of the Safavid state, Shah Ismail, took Baghdad and made a pilgrimage to Karbala and Najaf (the alleged birthplaces of Fuzuli) in 1508, the young poet Fuzuli recognized the power of Ismail in his first poem in Azeri Turkic "Hashish and Wine". Some researchers (such as the Italian Turkologist and Iranianist Alessio Bombachi) suggest that Fuzuli dedicated this creation to Shah Ismail, whom the poet praises in the preface to his poem.[10]

Some researchers believed that 1508 was the year of writing the poem. Nevertheless, the fact mentioned in the poem's dedication that, by the order of Shah Ismail, the Muhammad Shaybani, who was defeated in December 1510 in the battle of Merv, was killed, and his skull was decorated with gold inlays and served as a wine goblet, gives grounds to assert that "Bang-u-Bada" was written between 1510 and 1524 (the year of Shah Ismail's death).[11]

Content

The main characters of the poem are Bang (hashish) and Bada (goblet of wine), embodying the image of a proud and arrogant feudal lord who wants to gain dominion over the whole world - the main goals of Fuzuli's criticism. Both Bang and Bada wish to personally subjugate the whole world.[11]

The selfish Bang believes that all people should obey him alone.[11] He says:

It’s me who surpasses everyone in the world,

So, I deserve to be served by the people;

Is there a man who dares

Not bowing his head submissively before me?[12]

However, at a feast is revealed that Bang is just as proud as Bada. Bada even gets angry with his Cupbearer when hears from him praises addressed to Bang, suspecting him of secret obedience to Bang.[12] The dispute between the two narcissistic egoists ends in a war, as a result of which Bada wins. The result of the senseless war of these two sovereigns is the extermination of many people.[12]

Study and publication

The German researcher Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, who was the first to report about Fuzuli in the Western Europe, in the second volume of his work "Geschichte der Osmanischen Dichtkunst" lists the main works of Fuzuli, and dwells in detail only on his poem "Hashish and Wine", expounding and analyzing it. According to Hammer, the poem "Hashish and Wine" glorified Fuzuli, which the Azerbaijani researcher Hamid Arasli considers to be erroneous. After examining the poem, Hammer comes to the conclusion that "Fuzuli is one of the wine lovers (prohibited by the Koran) who prefers wine to hashish (which is also prohibited by the Koran)". According to Bertels, Hammer did not understand Fuzuli's language very well, concluding that Hammer's article could not have serious scientific significance.[1]

The Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences keeps 4 lists of the "Hashish and Wine" poem manuscripts.[5] In 1949, the Institute of Literature named after Nizami in Baku published the second volume of Fuzuli's "Works", which included the poem "Hashish and Wine". In 1958, the poem was published in the second volume of Fuzuli's "Works", in Russian, by the publishing house of the Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijan SSR, in Baku.[12]

Literary analysis

The poem is written in an allegorical form,[13] and, as noted by the literary critic Hamid Arasli, reproduces the war between the Safavids and the Ottoman Empire. In his poem, as Arasli notes, Fuzuli shows how meaningless this war was being caused by the desire for sovereignty of the two powerful sovereigns at that time. Also, the poet criticizes the pride and arrogance of the individual feudal lords.[11]

According to the Azerbaijani philologist Ziyaddin Goyushov, in the poem "Hashish and Wine", Fuzuli showed his negative attitude with regards to the ascetic sermons, opposing the earth joy to the "sweets of the afterlife." Fuzuli contrasted wine with kovsar, and earthly beauties - with houris. Fuzuli noted that one should not miss what is ("nagda") and think about what is not present ("nisie").[13] Goyushov writes that Fuzuli in his work skilfully exposes the moral shortcomings of his contemporaries-feudal lords, stigmatizes the Sultan, saying:[4]

You are slothful and stupid, a brainless bonehead,

What can be done in a moment, you can’t do in a year...

The source of troubles, vices, enmity, indeed you are

In the entire world, nobody's more terrible and uglier than you...

The Uzbek researcher Ergash Rustamov notes that Fuzuli's poem "Hashish and Wine" is a typical example of the genre "Munazar"[14] (the word "Munazar" in Arabic means dispute, competition),[15] which was very popular in the Eastern literature in the Middle Ages. According to Rustamov, Fuzuli wrote this work under the influence of the 15th century Uzbek poet Yusuf Amiri, who wrote a similar essay called "The Dispute Between Beng and the Wine".

According to the Azerbaijani researcher Gasim Jahani, while writing the poem "Bangu Bada", the main source to which Fuzuli appealed was Nizami Ganjavi's poem "Seven beauties". Nevertheless, in terms of the plot, the poem "Bangu-Bada" differs from the poems of Nizami Ganjavi.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 Arasly 1958, p. 13.

- 1 2 История Азербайджана. Vol. I. Baku: Издательство Академии наук Азербайджанской ССР. 1958. p. 252.

- 1 2 Jannat Naghiyeva (1990). Навои и азербайджанская литература XV-XIX вв. Tashkent: Издательство Фан Узбекской ССР. p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Goyushov 1968, p. 134.

- 1 2 Lyudmila Dmitrieva (1982). Исторические и поэтические тюркоязычные рукописи и их творцы (по материалам собрания Института востоковедения Академии наук СССР). Vol. V. Baku: Советская тюркология. p. 73.

- ↑ Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu (2006). История Османского государства, общества и цивилизации / History of the Ottoman state, society and civilization. Vol. II. Moscow: Восточная литература. p. 40.

- ↑ "FOŻŪLĪ, MOḤAMMAD". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ↑ Peter Rollberg (1987). The modern encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet literature (including Non-Russian and Emigre literatures). Vol. VIII. Academic International Press. p. 77.

- ↑ Elias John Wilkinson Gibb (1900–1909). A history of Ottoman poetry. Vol. III. London. p. 88.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Arasly 1958, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 Arasly 1958, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Arasly 1958, p. 133.

- 1 2 Goyushov 1968, p. 131.

- ↑ T.Hüseynova (1983). Историческое развитие жанровой формы муназара. Vol. IV. Baku: Известия Академия наук Азербайджанской ССР. Серия литературы, языка и искусства. p. 32.

- ↑ A.Ashurov (1983). Поэма Гаиби "Сказание о тридцати двух зернах" / Gaibi's poem "The Tale of the Thirty-two Seeds". Vol. III. Baku: Известия Академия наук Туркменской ССР. Серия общественных наук. p. 258.

- ↑ Gasim Jahani (1979). Азәрбајҹан әдәбијјатында Низами ән'әнәләри / Traditions of Nizami in Azerbaijani literature. Baku: Elm. p. 74.

Literature

- Arasly, Hamid (1958). Великий азербайджанский поэт Физули [The great Azerbaijani poet Fuzuli]. Baku: Азербайджанское издательство детской и юношеской литературы.

- Goyushov, Ziyaddin (1968). Этическая мысль в Азербайджане: исторические очерки [Ethical thought in Azerbaijan: historical essays]. Baku: Ganjlik.