Hamlet of La Houllière | |

|---|---|

Hamlet | |

.jpg.webp) The hamlet of La Houillère in the early 21st century. | |

Hamlet of La Houllière  Hamlet of La Houllière | |

| Coordinates: 47°32′35″N 6°39′19″E / 47.54306°N 6.65528°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté |

| Department | Haute-Saône |

| City | Ronchamp and Champagney |

| Naighborhood | Arrondissement of Lure |

| District | Champagney canton |

| Elevation | 381 m (1,250 ft) |

| Urbanization stages | Since the end of the 18th century |

| Touristic sites | Ancient mines |

| City function | Residential and forest zone |

The hamlet of La Houillère is located in the French communes of Ronchamp and Champagney, in the heart of the mining region, in the Haute-Saône département of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region.

It was created after the discovery of the Ronchamp coal mines and became the center of mining operations from the second half of the 18th century to the first half of the 19th century. It was designed to be independent of neighboring villages. The hamlet quickly lost interest in the course of the 19th century, as mining operations moved further and further south of the coalfield. Despite this, certain company buildings such as the infirmary, stable and château de la Houillère continued to operate until the mines closed in 1958. At the beginning of the 21st century, few traces of the mining installations remain, but the hamlet is still inhabited. All eight workers' houses are listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage as the "cité ouvrière de la Houillère" (Houillère working-class housing estate).

Geography

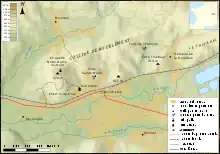

.jpg.webp)

Location

The hamlet is located in a small valley in the Chevanel woods,[p 1] between the communes of Ronchamp and Champagney, in Haute-Saône, eastern France,[a 1] 1.5 kilometers from the center of Ronchamp and 2.5 kilometers from the center of Champagney.[1]

The town is part of the Champagney canton and belongs to the Rahin and Chérimont community of communes.

Topography

The hamlet of La Houillère nestles in a small valley running northeast-southwest, bordered by small wooded hills belonging to the same mountain range as the hill of Bourlémont, and is part of the Ballons des Vosges Nature Park. The altitude at the center of the hamlet is 381 meters.[2]

Geology

The hamlet was built on the Haute-Saône plateau in the sub-Vosgian depression,[3] on the southern slopes of the Vosges mountains.[4]

It is part of the sub-Vosgian coalfield, which consists of two layers of coal (varying in thickness from a few centimeters to three meters) in a quadrilateral five kilometers long and two kilometers wide.[p 2] The coal deposit is overlain by red sandstone and various types of clay.[a 2]

Coal began to form 300 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period. The transformation of plant litter took place over a period of 20 million years to form coal. During this phase, organic sediments collected in a basin and were covered by alluvial deposits.[5]

Hydrography

Several mountain streams irrigate the surrounding area and flow into the Rahin to the south. Two ponds are located nearby: Fourchie pond, fed by mine water drained by the large drainage channel, and a small artificial pond created as a reservoir in case of fire. They can be seen along the historic outcrop circuit.[a 3][a 4]

The large drainage channel, which evacuates the mine water from the drainage, passes under the hamlet and feeds the Fourchie pond.[a 5]

Transportation and communications

The Paris-Mulhouse railway line passes south of the hamlet. The Ronchamp colliery station was built during the mining era. It was used to transport coal. Three roads cross the hamlet, two of them leading to Ronchamp from the west and south, the third to Champagney to the east.[6]

Toponymy

The Cassini map, drawn up in the 18th century, mentions "mines de Houilles". The name "Houillères", derived from coal mining, was given to the new hamlet subsequently built on this site.[p 3]

History

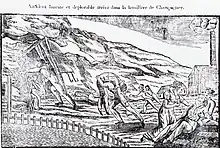

The Chevanel coalfields were officially discovered in the mid-18th century.[p 4] Two separate concessions were granted in 1757, then combined in 1768.[a 2] Numerous hillside tunnels and small, shallow shafts were then dug in the small valley where the future hamlet of La Houillère would be located.[p 1]

Around 1760, the first buildings were erected near the tunnels: a number of warehouses, the manager's lodgings, the houses of the farriers and the bakers, and a shingle-covered stone building shared by three families of workers.[p 5]

In 1810, the company started digging its first real shaft, the Saint-Louis shaft, which mined coal at a depth of over one hundred metres from 1823 to 1842. This shaft also experienced two blasts of firedamp, including the first in the mining basin on April 10, 1824, which killed twenty people and injured sixteen others.[a 6] Another shaft was dug further north, the Henri IV shaft, which produced very little coal and was mainly used for ventilation and drainage of the Saint-Louis shaft.[a 6] In 1819, the first steam engine used for mining in Ronchamp was installed at the Saint-Louis shaft.[a 6]

In 1825, a cantina, an inn and a large multi-storey residential building were built.[p 6] Twenty-five years later, new industrial buildings and housing were added,[p 6] including the Château de la Houillère, the school and the infirmary, followed by the Plateforme housing estate in 1854.[p 7] After the closure of the Saint-Louis shaft, its various buildings were demolished, except for one, which was converted into a casino, multi-purpose hall and bar-tabac. Further on, the former glassworks was transformed into an assembly hall with balconies and a theater stage.[a 1]

The hamlet quickly lost its industrial appeal in the 19th century, as mining operations moved to the center and then south of the coalfield. However, company buildings such as the infirmary, the stable and the Château de la Houillère remained in use until the end of mining.[a 1] In the 1950s, when the outcrops were once again mined, a number of construction sites were opened near the hamlet, including the Datout gallery and two pumping stations.[p 8]

After the mines closed in 1958, the casino and part of the infirmary were demolished, and the Château de la Houillère was abandoned.[a 1] In 2000, the large multi-storey building was destroyed by fire.[p 1][p 6] The stable opposite the Saint-Louis shaft, bought by a private owner, was also destroyed by fire. The ruins remained until their demolition on May 31, 2006.[7] At the beginning of the 21st century, no trace remained of the Saint-Louis and Henri IV mines,[a 7] but a number of buildings remained and were inhabited,[a 1] and two tunnels (Datout and Dubois) were redeveloped.[a 8] In September 2012, a decorative monument to the site's mining history was built on the site of the former Saint-Louis mine.[8]

Demographic evolution

In 1768, the hamlet had just ten inhabitants. But with the development of mining activity, the population grew rapidly over the course of the 19th century, reaching several dozen inhabitants around 1850.[p 5] The increase in population was proportional to that of the two communes to which the hamlet belonged. Despite deindustrialization, the hamlet did not disappear. Even after the mines closed, new inhabitants moved in.[a 1]

Description

Mines and industries

The hamlet of La Houillère was highly industrialized between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries, having been created from scratch in the middle of a forest to facilitate coal mining. Each hillside is pierced by several tunnels and small adits (most of which do not lead to the surface).[p 9] Alongside the roads, coal yards were built, along with warehouses and sorting buildings. Small factories were also set up in the hamlet, including an alum factory, a glassworks and a factory producing lampblack and bitumen.[p 10]

In the 1810s, the company's first two shafts were dug in the hamlet: the Saint-Louis coal mine and the Henri IV coal mine.[p 6] The Saint-Louis mine had several buildings to sort the coal and house the various machinery (winding engine and pumps powered by a steam engine, and the horse-drawn engine still in place), and was recognizable by its large flue-gas stack overlooking the hamlet. The Henri IV well, with its less imposing infrastructure, was mainly used for dewatering and aerating the Saint-Louis works, using pumps driven by oxen. The water was released into the large drainage channel that crossed the hamlet from east to west.[a 6]

To the south of the hamlet, the company-owned railway station was used to switch coal trains between the various shafts and the line from Paris-Est to Mulhouse-Ville.[a 9] Nearby were also the offices and workshops of the collieries, now the premises of MagLum, as well as the Saint-Charles shaft and its slag heaps.

Housing

The hamlet of La Houillère comprises dozens of different types of housing, built between 1760 and 1850 by the Ronchamp coal-mining company in a haphazard fashion to meet labor needs, with no urban planning.

There were dormitories for single miners or those working weekdays (at first, they slept on straw mats on the floor, with only one stove per floor), which were later converted into apartments for miners' families. There are also phalanstères with wooden staircases and walkways. The Plateforme mining estate, comprising eight houses, was built in 1854 opposite the Saint-Louis shaft, then converted into a casino.[p 11] It is listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage as the "cité ouvrière de la Houillère".[9]

There are also individual houses reserved for master miners and engineers, as well as a manor house known as the Château de la Houillère. Since the 1850s, the latter has been the managers' official residence; prior to this date, they lived in a more modest dwelling topped by a bell tower, where a small bell rang when work began and ended.[a 1][p 12][10]

Despite deindustrialization, new pavilions were built long after the mines closed in the 20th and 21st centuries.[a 1]

The northern part of the hamlet, where the dwellings were located in 1826.

The northern part of the hamlet, where the dwellings were located in 1826. The Plateform city.

The Plateform city..jpg.webp) Another view of the same mining town.

Another view of the same mining town. The château de la Houillère.

The château de la Houillère..JPG.webp) The directors' former home.

The directors' former home.

Facilities

In addition to housing and industrial facilities, the hamlet included a number of outbuildings to serve the residents. For catering purposes, a cantina and inn were built in 1825.[p 6] Around 1850, a school was built.[p 7] The company also built warehouses and an infirmary-hospital reserved for employees,[p 6] housed in a tall building with care and rest rooms, as well as accommodation for the nurse who had to provide food and guard duty. By 1919, a doctor, a nurse and midwives were serving the population of the coalfield.[11] To meet hygiene needs, clean water was pumped from a stream to a hilltop reservoir, which in turn supplied the hamlet's fire hydrants.[a 10] Some disused industrial buildings were converted into assembly halls, a bar-tabac, a theater and a casino.[a 1] At the beginning of the 21st century, the only existing service in the hamlet was a public nursery school.[12]

.JPG.webp) The old mine infirmary.

The old mine infirmary..JPG.webp) Remains of the water reservoir that supplied the hamlet.

Remains of the water reservoir that supplied the hamlet..JPG.webp) One of the fire hydrants.

One of the fire hydrants.

Personalities linked to the hamlet

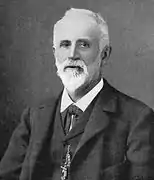

- Auguste Lalance (1830-1920), industrialist and politician born in the hamlet, son of a coal mining engineer.[a 1][a 11]

- Léon Poussigue (1859-1941), director of the Ronchamp mines (1891-1919) and resident at Château de la Houillère, creator of the Arthur-de-Buyer coal mine.

Auguste Lalance.

Auguste Lalance. Léon Poussigue.

Léon Poussigue.

See also

References

Les Houillères de Ronchamp of Jean-Jacques Parietti

- 1 2 3 Parietti 2001, p. 11.

- ↑ Parietti 2001, p. 80.

- ↑ Parietti 2010, p. 14.

- ↑ Parietti 2001, p. 7.

- 1 2 Parietti 2010, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Parietti 2010, p. 99.

- 1 2 Parietti 2010, p. 102.

- ↑ Parietti 2001, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Parietti 2001, pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Parietti 2001, p. 9.

- ↑ Parietti 2010, pp. 100–102.

- ↑ Parietti 2010, pp. 102–104.

Association of Friends of the Mine Museum

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Description and photographs of the hamlet of La Houillère" (in French)..

- 1 2 "The Ronchamp coalfield and concessions" (in French)..

- ↑ "The outcrop mining circuit" (in French)..

- ↑ Historical tour of the Etançon outcrops from the Ronchamp coal mines.(in French)

- ↑ "The large drainage channel" (in French)..

- 1 2 3 4 "History of the Saint-Louis shaft" (in French)..

- ↑ "Vestiges des puits de mine" (in French)..

- ↑ "Tous les travaux des amis du musée de la mine" (in French)..

- ↑ "Le réseau ferré installé entre les puits" (in French)..

- ↑ "Vestige du réservoir d'eau" (in French)..

- ↑ "Auguste Lalance" (in French).

Other sources

- ↑ Measurements carried out on Google Earth.

- ↑ "La carte du parc". le site du parc naturel régional des ballons des Vosges (in French). Retrieved December 21, 2013..

- ↑ "La dépression sous-vosgienne". caue franche (in French)..

- ↑ "Carte du massif des Vosges" (pdf) (in French). Retrieved October 10, 2015..

- ↑ PNRBV, p. 5.

- ↑ "Plan". Carte Michelin (in French)..

- ↑ "Les écuries des Houillères de Ronchamp". Alain Jacquot-Boileau's blog (in French). October 31, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2013..

- ↑ "Le bassin houiller refait surface". the website of the daily newspaper L'Est républicain (in French). September 8, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2013..

- ↑ Base Mérimée: Cité ouvrière de la Houillère, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French).

- ↑ PNRBV, p. 21.

- ↑ PNRBV, p. 19.

- ↑ "École maternelle publique Hameau de la Houillère". le site du ministère de l'Éducation nationale (in French). Retrieved 21 December 2013..

Bibliography

Documents used to write this article.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2001). Les Houillères de Ronchamp vol. I: La mine (in French). Vesoul: Éditions Comtoises. ISBN 2-914425-08-2.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2010). Les Houillères de Ronchamp vol. II: Les mineurs (in French). Noidans-lès-Vesoul: fc culture & patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-36230-001-1.

- PNRBV. Le charbon de Ronchamp (in French). Déchiffrer le patrimoine, Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges. ISBN 978-2-910328-31-3.