A hackamore is a type of animal headgear which does not have a bit. Instead, it has a special type of noseband that works on pressure-points on the face, nose, and chin. Hackamores are most often seen in western riding and other styles of riding derived from Spanish traditions, and are occasionally seen in some English riding disciplines such as show jumping and in the stadium phase of eventing. Various hackamore designs are also popular for endurance riding. While usually used to start young horses, hackamores are often seen on mature horses with dental issues that would make the use of a bit painful, and on horses with mouth- or tongue-injuries that would be aggravated by a bit. Some riders also like to use them in the winter to avoid putting a frozen metal bit into a horse's mouth. In the Charro tradition of Mexico, the jáquima and bozal substituted for the serrated iron cavesson used in Spain for training horses.[1][2]

There are many styles, but the classic hackamore uses a design featuring a bosal noseband, and is sometimes itself called a "bosal" or a "bosal hackamore". It has a long rope-rein called a mecate and may also add a type of stabilizing throatlatch called a fiador, which is held to the hackamore by a browband. Other designs with heavy nosebands are also called hackamores, though some bitless designs with lighter-weight nosebands that work with tension rather than with weight are also called bitless bridles. A noseband with shanks and a curb chain to add leverage is called a mechanical hackamore, but is not considered a true hackamore. A simple leather noseband, or cavesson, is not a hackamore; a noseband is generally used in conjunction with a bit and bridle. In 1844, Domingo Revilla defined and described the jáquima and bozal used in Mexico as follows:[3]

Jáquima is a kind of leather or horsehair bozal, secured with a harness of the same material, and at the base of the bozal that remains next to the horse's chin, there is a strap to further secure it, and it is called a fiador. The bozalillo is just the bozal without harness or without a fiador. There are very curious jáquimas and bozalillos, and both are very necessary for the horse.

In his book Vocabulario de Mexicanismos (1899), Mexican historian and philologist Joaquín García Icazbalceta defined the bozal or bozalillo (known as a "bosalita" in the USA) as follows:[1]

Bozalillo: It is not a diminutive of Bozal, but a kind of fine jáquima made of twisted horsehair that is placed under the bridle of the horses; and from the part that surrounds the mouth hangs the falsarrienda [false reins]. It replaces the serrated cavesson, not used here.

Like a bit, a hackamore can be gentle or harsh, depending on the hands of the rider. The horse's face is very soft and sensitive, with many nerve endings. Misuse of a hackamore can cause pain and swelling on the nose and jaw, and improper fitting combined with rough use can cause damage to the cartilage on a horse's nose.

Origins

The word "hackamore" is derived from the Spanish word jáquima, meaning headstall or halter, specifically the rope halter used for tethering and leading animals, itself derived from Old Spanish xaquima.[4][5][6] Historically, in Spain jáquima was the bridle used for riding on donkeys and mules.[7] The Spanish had obtained the term from the Arabic šakīma (bit), from šakama (to bridle).[8] From the Americanized pronunciation of jáquima, the spelling "hackamore" entered the written English language by 1850,[9] not long after the Mexican–American War. In Spain and Hispanic America, jáquima is generally any type of halter used for tethering and leading animals, but in Mexico and certain parts of South America, Jáquima also refers to a special type of halter, specifically a bozal (noseband), used for training horses; such Jáquimas tend to be thicker and stronger than the regular ones for tethering.[10][11][12]

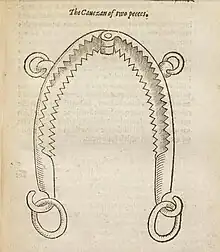

The first hackamore was probably a piece of rope placed around the nose or head of a horse not long after domestication, perhaps as early as 4,000 BC.[13] Early devices for controlling the horse may have been adapted from equipment used to control camels.[14] Over time, more sophisticated means of using nose pressure were developed. The Persians beginning with the reign of Darius, c. 500 BC, were one of the first cultures known to have used a thick-plaited noseband to help the horse look and move in the same direction.[14] This device, called a hakma, also added a third rein at the nose, and was an innovation that allowed a rider to achieve collection by helping the horse flex at the poll joint.[14] The third rein later moved from the top of the noseband to under the chin,[15] where it is still part of the modern mecate rein used on the bosal-style hackamore. The techniques of horse-training refined by the Persians later influenced the works on horsemanship written by the Greek military commander Xenophon.[16] This heavy noseband itself came to be known by many names, retaining the name hakma in Persio-Arabic tongues, but becoming the cavesson in French, the cavezzone[17] or capezzone[18] in Italy, the cabezon[19] or media caña[20] in Spain, and bozal or bosal in Mexico.[14] Another modern descendant is the modern longeing cavesson which includes a heavy noseband with a rein at the nose, but it is used for longeing, not for riding.

The tradition of hackamore use in the United States came from the Spanish Californians, who were well respected for their horse-handling abilities.[21] From this tradition, the American cowboy adopted the hackamore and two schools of use developed: The "buckaroo" or "California" tradition, most closely resembling that of the original vaqueros, and the "Texas" tradition, which melded some Spanish technique with methods from the eastern states, creating a separate and unique style indigenous to the region.[22] Today, it is the best known of the assorted "bitless bridling" systems of controlling the horse.[23] English journalist and artist, William Redmond Ryan (1823 - 1855), described the Californio method for taming horses using a jáquima, which he calls “hackamore”, while living in California in the 1840s:[24]

The animals having been chased inside the fence, the ranchero selects the horse that pleases him most, and the lasso is thrown round his neck. He is then led or driven out of the correl, and, being thrown down, his legs are tied; a leathern blind is attached to the hackamore placed ready for that purpose on his forehead, and a strap fastened loosely round his body. The lasso is then tied to the hackamore immediately beneath the mouth, and he is thus completely secured. His legs are set free after this operation, but he is still held by the lasso. He now begins to kick and plunge furiously, but soon getting tired of this amusement, the person who holds the lasso draws it in gradually with a gentle strain until he can reach the animal's head,which he pats as soothingly as possible. He then draws the blind down over his eyes, and jumps on his back, slipping his knees between the strap and the horse's sides. This operation is generally performed by an Indian, who is accustomed to ride in this fashion without either saddle or blanket. The blind is now lifted, and the horse, unused to the burden that he bears, begins rearing and plunging again, and keeps it up sometimes for a whole hour. All this time the Indian is trying to guide him, but at first without success. At last the animal gets exhausted, and moves along with greater docility. The rider then takes him home, and, choosing a spot where there is sufficient grass, sinks a strong stake of wood in it, and, attaching the animal to it, leaves him alone for the remainder of that day. On the following, and, perhaps, for eight successive days, according to circumstances, he repeats the same operation; and then, if he considers him sufficiently broken in, puts on the saddle, his eyes being still kept covered. When the saddle is first put on, the trainer does not mount him, but allows him to kick and plunge about until he gets a little familiarized to it. He then rides the horse with a saddle for a few days, and puts on a bridle. He is still led, however, by the hackamore, the object of putting on the bridle being merely to accustom him to it. In this way some horses may be tamed in a month, whilst others will take two or three. Others, again, can never be broken in sufficiently for any ordinary rider to mount them without danger. Of the wild horses subjected to this process of training, at least one fourth are killed, and a still larger proportion seriously injured.

Although the method described by Redmond, using a type of jáquima before putting on the bridle, resembles the method used by the Charros in Central Mexico, it was done differently, in a haphazardly way, by the Californios who used violent methods to expedite the process, probably as a result of being something new to them. Frank Marryat, an English sailor and artist that lived in California, also described the method used by the Californios for training horses but mentions that the bit and bridle is put on and used from the beginning, never mentioning the use of a jáquima or “hackamore”:[25]

When the tame horses attached to a ranche begin to be "used up" with hard work, and the stud requires replenishing, the "vaccaros" start for the mountains, and return shortly driving before them a band of wild colts, which, with some difficulty, they force into the corral, where they are enclosed.

The "vaccaros" now enter to select the likely colts, the mad herd fly round the corral, but the unerring lasso arrests the career of the selected victim, who is dragged, with his fore feet firmly planted in the ground, half-strangled, to the court yard, where a strong leather blind is at once placed over his eyes; at this he hangs his head, and remains quite still, his fore feet still planted in the ground ready to resist any forward movement. Then the "vaccaro", always keeping his eye on the horse's heels and mouth, places a folded blanket on his back, and on that the saddle, divested of all incumbrances, this he girths up with all his power; the bridle is on in an instant, so simple is its construction; how free from ornament is the bit, how plain and unpretending is that rusty iron prong, which, at the least pressure on the rein, will enter the roof of the horse’s mouth. Now the “vaccaro" is seated, and nothing remains but to remove the blind; this is done by an assisting "vaccaro", who gets bit on the shoulder for his trouble, and the work begins. Single jumps, buck jumps, stiff-legged jumps; double kicks; amalgamated jumps and kicks, aided by a twist of the back bone; plunges and rears; these constitute his first efforts to dislodge the "vaccaro," who meets each movement with a dig of his long iron spurs: then the horse stands still and tries to shake his burden off, finally he gives a few mad plunges in the air, and then falls down on his side.

It is now that the formation of the Californian saddle and the large wooden stirrups protect the rider: a small bar lashed crossways to the peak of the saddle prevents the horse from rolling over, and when he rises his tormentor rises with him unhurt; finding all efforts useless, he bounds into the plain, to return in a few hours sobbing, panting, but mastered. The blind is again put on, the saddle and bridle removed, several buckets of cold water are thrown over his reeking sides, and he is turned into the "corral", an astonished horse, to await the morrow, when his lesson will proceed, and receive less opposition from him! In three days he is considered broken, and is called a “manzo", or tame horse, but admirably as docility has been inculcated in this short period, he is not yet by any means the sort of horse that would suit those elderly gentlemen who advertise in the "Times” for a “quiet cob", nor indeed is he fit for anyone but a Californian "vaccaro".

In his book —A Tour of Duty in California (1849)— American navy and army officer, Joseph Warren Revere, also describes the method used by the Californios for taming horses, but just like Frank Marryat, he never mentions the use of a jáquima, hackamore or bosal, stating that the bridle is put on and used from the beginning:[26]

In the plains of the Tulares natural corrals exist, formed by glens in the sierra, which are surrounded by precipices, up which a goat could hardly climb. To these the people of the settlements proceed en masse, and surrounding a large caballada of wild horses, pursue them through the narrow inlet to the selected glen or dell, the entrance to which they speedily close with branches previously collected by their vaqueros, or the neighboring Indians, the latter being always on hand on such occasions —not to get horses to ride, but to eat. The rancheros then enter the natural corral on horseback, with the ready riata, and selecting such a horse as suits their fancy, he is speedily noosed, and despite his struggles and plunging, is led out, and delivered into the custody of the vaquero. Suddenly the wild and trembling animal is thrown rudely to the ground, and in a trice is bridled, and bitted with the formidable Spanish bit, capable of breaking the jaw of the most refractory beast. The Californian immoveable saddle is then lashed on his back, and he is forthwith mounted by a rider equipped with the rowels. A scene of contention for the mastery then ensues between the man and horse; but the former, aided by his powerful machinery, invariably comes off victor of the field. The horse submits like a sensible and generous foe, tacitly acknowledges the superiority of the man, and never requires a second lesson. Sometimes a corral is made on the plain itself, but this is rare, as it is "mucho trabajo." A more common way is to give chase to a caballada on the open plain, the pursuit being maintained by well-mounted cavaliers, until the colts and weaker horses of the herd give in, when they are successively lassoed as fast as overtaken. Mares are seldom ridden, and are so abundant in the wild state, that horses must always be plentiful in that glorious country.

The tame horses are colts taken from the manadas, on the ranchos of the proprietors. They are broken to the bit and saddle in the same rough manner as the wild horse, and after being once subjected, they may be ridden by almost anybody. Often, however, they are gradually broken while yet little colts, by the children of the ranchos.

The word "hackamore" has been defined many ways, both as a halter[27] and as a type of bitless bridle.[28] However, both terms are primarily descriptive. The traditional jaquima hackamore is made up of a headstall, bosal and mecate tied into looped reins and a lead rope.[23] It is neither precisely a halter nor simply a bridle without a bit. "Anyone who makes the statement that a hackamore is just another type of halter ... is simply admitting that he knows nothing about this fine piece of equipment."[29]

Types

Today, hackamores can be made of leather, rawhide, rope, cable or various plastics, sometimes in conjunction with metal parts. The main types are the classic bosal and the more modern sidepull, though other designs based on nose pressure loosely fall into this category. Other assorted designs of bitless headgear, often classed as "bitless bridles", are not true hackamores. These include the "cross-under" bitless bridle, which uses strap tension to control the horse, and the mechanical "hackamore", which has leverage shanks.

Bosal

The bosal (/boʊˈsɑːl/, /boʊˈsæl/ or /ˈboʊsəl/; Spanish pronunciation: [boˈsal]) is the noseband element of the classic jaquima or true hackamore. The bosal is seen primarily in western-style riding. It is derived from the Spanish tradition of the vaquero.[21] It consists of a fairly stiff rawhide noseband with reins attached to a large knot or "button" (Sp. bosal) at the base from which the design derives its name. The reins are made from a specially tied length of rope called a mecate (/məˈkɑːteɪ/ in this usage; Spanish pronunciation: [meˈkate]), which is tied in a specific manner to both adjust the size of the bosal, and to make a looped rein with an extra length of rope that can be used as a lead rope. In the Texas tradition, where the bosal sets low on the horse's face, and on very inexperienced ("green") horses in both the California (vaquero) and Texas traditions, a specialized rope throatlatch called a fiador /ˈfiːədɔːr/ is added, running over the poll to the bosal, attached to the hackamore by a browband.[30] The fiador keeps a heavy bosal properly balanced on the horse's head without rubbing or putting excess pressure on the nose. However, it also limits the action of the bosal, and thus is removed once the horse is comfortable under saddle.[31] The terms mecate and fiador have at times been Americanized as "McCarty" or "McCarthy" and "Theodore", but such usage is considered incorrect by hackamore reinsmen of the American West.[29]

In the Mexican Charro tradition, the Charros would start a young horse, between four and five years old and typically wild, in a Jáquima and bozal. This method of training horses was originally known in Mexico as “the Mesquital Method” because it was developed by the Charros of the Mezquital Valley in Central Mexico.[32] The Charros would teach the horse everything, absolutely everything, with the bozal, only introducing the bit much later after the horse had learned everything. The Charros had five stages for the horse:[33][34][35]

“Caballo Bronco”: the wild horse that has never been ridden.

“Caballo quebrantado”: the semi-broken horse.

“Caballo de falsa rienda” or “Caballo de una rienda”: the “false-rein horse” or “one-rein horse”, or the horse being ridden only with the bozal.

“Caballo de dos riendas”: the “two-rein horse”, or the horse being ridden with both the bozal and the bit.

“Caballo de rienda limpia” or “rienda pelona” or “caballo hecho”: the “made horse”, the horse being ridden only with the bit, the final stage of its education.

In the Charro tradition, the transition from the bozal into the bit was only a formality, as the horse had already been taught everything with the bozal. The bit only serves as a status symbol, rather than an actual need.

The bosal acts on the horse's nose and jaw, and is most commonly used to start young horses under saddle in the Vaquero tradition of the "California style" cowboy. The bosal is a very sophisticated and versatile style of hackamore. Bosals come in varying diameters and weights, allowing a more skilled horse to "graduate" into ever lighter equipment. Once a young horse is solidly trained with a bosal, a bit can be added and the horse is gradually shifted from the hackamore to a bit. While designed to be gentle, Bosals are equipment intended for use by experienced trainers, as they can be confusing in the wrong hands.

The bosal acts as a signal device providing a pre-signal to the horse by the lifting of the heel knot off the chin when the rider picks up on a rein. This gives the horse time to be prepared for the impending cue. Hackamores are traditionally used one rein at a time, with fluctuating pressure. Pulling back on both reins with steady pressure teaches a horse to brace and resist, which is the opposite of the hackamore's intention. Hackamores are used in the classic Vaquero tradition to teach young horses softness, and to give readily to pressure while leaving the mouth untouched for the spade bit later on in training. Bosals come in varying diameters and weights, allowing a more skilled horse to "graduate" into ever lighter equipment. Once a young horse is solidly trained with a bosal, a spade bit is added and the horse is gradually shifted from the hackamore to a bit, to create a finished bridle horse. Some horses are never transitioned to a bitted bridle, and it is possible to use the hackamore for the life of the horse.

Sidepulls

The sidepull is a modern design inspired by the bosal, though it is not a true hackamore. It is a heavy noseband with rings that attach the reins on either side of the head, allowing very direct pressure to be applied from side to side. The noseband is made of leather, rawhide, or rope with a leather or synthetic strap under the jaw, held on by a leather or synthetic headstall. Sidepulls are primarily used to start young horses or on horses that cannot carry a bit.

While severity can be increased by using harder or thinner rope, a sidepull lacks the sophistication of the bosal. The primary advantage of a sidepull over the bosal is that it gives stronger direct lateral commands and is a bit easier for an unsophisticated rider to use. Once a horse understands basic commands, however, the trainer needs to shift to either a bosal or to a snaffle bit to further refine the horse's training. If made of soft materials, a sidepull may also be useful for beginners so that they do not injure their horse's mouth as they learn the rein aids.

English riders sometimes use a jumping cavesson, or jumping hackamore, which is a type of hackamore that consists of a heavy leather nosepiece (usually with a cable or rope inside) with rings on the sides for reins, similar to a sidepull, but more closely fitting and able to transmit more subtle commands. A jumping cavesson is put on a standard English-style headstall and often is indistinguishable at a distance from a standard bridle. It is often used on horses who cannot tolerate a bit or on those who have mouth or tongue injuries.

Mechanical hackamore

A mechanical hackamore, sometimes called a hackamore bit, English hackamore, or a brockamore, falls into the hackamore category only because it is a device that works on the nose and not in the mouth. The mechanical hackamore uses pressure on the chin and the nose to guide the horse. A mechanical hackamore uses shanks and leverage, thus it is not a true hackamore.[36] Because of its long, metal shanks and a curb chain that runs under the jaw, it works similarly to a curb bit. The ability to apply leverage creates a high risk of abusive use in the hands of a rough rider.[36] Mechanical hackamores lack the sophistication of bits or a bosal, cannot turn a horse easily, and primarily are used for their considerable stopping power.[37] While the bosal hackamore is legal in many types of western competition at horse shows, the mechanical hackamore is not allowed;[38] its use is primarily confined to pleasure riding, trail riding, and types of competition such as rodeos, where bitting rules are fairly lenient.

Proper use

The proper use of a hackamore can vary depending on the rider's intentions. Riding a horse with a hackamore for pleasure and riding a horse with a hackamore for work will require totally different understandings of how the tack works. When riding with a hackamore for working purposes it is important to make sure both the horse's neck and chin are being engaged with the reins. The way the rider holds his or her hands is also very important when working with a hackamore. The way the hands are held will affect how the reins are pulled which will affect how and where the pressure is being put on the horse. When pulling on the reins to guide the horse one should pull the reins towards his or her hips to get the proper movement from the horse.[39]

Other equipment

Like the mechanical hackamore, various modern headstall designs known as "bitless bridles" or "cross-under bitless bridles" are also not a true hackamore, even though they lack a bit. These devices use various assortments of straps around the nose and poll to apply pressure by tightening the headstall in particular areas. They are not as subtle as a bosal, but serve many of the same purposes as a sidepull and are generally milder than most mechanical hackamores.

Some people also ride horses with a halter. A closely fitted rope halter with knots on the nose, a bosal-like button at the jaw and two reins attached may act in a manner similar to a sidepull or mild bosal. In contrast, use of an ordinary stable halter as headgear to control a horse is, as a rule, a dangerous practice because the stable halter has no way of increasing leverage to exert control by the rider if a horse panics.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 García Icazbalceta, Joaquín (1899). Vocabulario de Mexicanismos. Mexico: La Europea. p. 58. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ↑ Rincón Gallardo, Carlos (1938). El Libro del Charro Mexicano. Mexico: Imprenta Regis. pp. 5, 113. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ↑ Revilla, Domingo (1844). El Museo Mexicano. Mexico: Ignacio Cumplido. p. 553. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ↑ Diccionario de la Lengua Castellana. Madrid: Imprenta de Francisco del Hierro. 1739. p. 535. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ "Jáquima". Real Academia Española. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, [hackmore] OED online edition, accessed Feb. 20, 2008

- ↑ Ellies Du Pin, Louis; Veyrac, Jean de; Morgan, Joseph (1724). The History of the Revolutions in Spain. London: W. Mears. p. xiii. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ "hackamore." The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 24 Feb. 2008. Dictionary.com <http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/hackamore>.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, [hackamore] OED online edition, accessed Feb. 20, 2008

- ↑ Atl., Dr. (1922). Las artes populares en México. Mexico: Cvltvra. p. 251. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ Rincón Gallardo, Carlos (1939). El Libro del Charro Mexicano. Mexico: Regis. p. 73. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ Taylor, Louis (1965). Out of the West. New York: A. S. Barnes. pp. 19, 20. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ↑ R.M. Miller, p. 222

- 1 2 3 4 Bennett, pages 54-55

- ↑ Bennett, page 60

- ↑ Bennett, page 57

- ↑ Locatelli, Antonio (1825). Il perfetto cavaliere. Milan: Sonzogno. p. 279. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ↑ "LA MONTA MAREMMANA". Associazione Butteri D'Alta Maremma. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ↑ Cubillo y Zarzuelo, Pedro (1862). Tratado de hipología para el uso de los caballeros cadetes del arma de cabellería. Madrid: Manuel Minuesa. p. 325. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ↑ Sampedro y Guzmán, Fernando (1851). Higiene veterinaria militar. Madrid: Imprenta de Tomás Fortanet. p. 228. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- 1 2 Connell, page 4

- ↑ R.W. Miller, p. 103

- 1 2 R.M. Miler, p. 225

- ↑ Redmond Ryan, William (1850). Personal Adventures in Upper and Lower California, in 1848-9 Volume 1. London: W. Shoberl. pp. 100, 101, 102. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ↑ Marryat, Frank (1855). Mountains and Molehills: or, Recollections of a burnt journal. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 74, 75, 76. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ↑ Warren Revere, Joseph (1849). A Tour of Duty in California. New York: C.S. Francis & Company. p. 106. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ↑ see, e.g. Rollins, page 151: "The antithesis of the severe bit was the 'hackamore' (from Spanish 'jáquima,' a halter)."

- ↑ see, e.g. Brown, Mark Herbert and William Reid Felton. Before Barbed Wire, 1956, p. 219: "A hackamore is the bitless bridle, so to speak, which is put on a wild horse as his first introduction to the bridle"

- 1 2 Williamson, pp. 13–14

- ↑ A bosal hackamore with a fiador

- ↑ Jaheil, Jessica. "Bosal, snaffle, spade - why?" Horse Sense, web page accessed July 11, 2011

- ↑ Revilla, Domingo (1844). El Museo Mexicano o Miscelánea de Amenidades Curiosas e Instructivas, Volume 3. Mexico: Ignacio Cumplido. p. 558. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Laurent, Paul (1867). La guerre du Mexique de 1862 à 1866. Paris: Amyot. p. 288. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ↑ Sánchez Navarro, Juan (1974). "Arte de Amansar y Arrendar Un Potro". Artes de México (174): 13–22. JSTOR 24317566. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ↑ Sánchez Navarro, Juan; Icaza, Ernesto (1984). La Doma Mexicana el Arte de Arrendar un Caballo Criollo. Mexico: J. Sánchez Navarro. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- 1 2 R.M. Miller, p. 227

- ↑ Ambrosiano, Nancy. "All About Bitless Bridles" Equus, March, 1999. Archived 2008-01-19 at the Wayback Machine Web page accessed February 25, 2008

- ↑ USEF rulebook

- ↑ name="Corey"

References

- Bennett, Deb (1998) Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship. Amigo Publications Inc; 1st edition. ISBN 0-9658533-0-6

- Connell, Ed (1952) Hackamore Reinsman. The Longhorn Press, Cisco, Texas. Fifth Printing, August, 1958.

- Corey Cushing, W. (2018, February 21). Riding With a Hackamore or Bosal. Retrieved September 14, 2020, from https://horseandrider.com/how-to/riding-with-a-hackamore

- Miller, Robert M. and Rick Lamb. (2005) Revolution in Horsemanship Lyons Press ISBN 1-59228-387-X

- Miller, Robert W. (1974) Horse Behavior and Training. Big Sky Books, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT

- Rollins, Philip A. (1922) The Cowboy: His Character, Equipment and His Part in the Development of the West, C. Scribner's sons, 353 pages.

- Second opinion doctor. (n.d.). Retrieved September 14, 2020, from http://www.second-opinion-doc.com/horse-bridles-benefits-of-using-a-hackamore.html

- Williamson, Charles O. (1973) Breaking and Training the Stock Horse. Caxton Printers, Ltd., 6th edition (1st Ed., 1950). ISBN 0-9600144-1-1