| Great dodecahedron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron |

| Stellation core | regular dodecahedron |

| Elements | F = 12, E = 30 V = 12 (χ = -6) |

| Faces by sides | 12{5} |

| Schläfli symbol | {5,5⁄2} |

| Face configuration | V(5⁄2)5 |

| Wythoff symbol | 5⁄2 | 2 5 |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry group | Ih, H3, [5,3], (*532) |

| References | U35, C44, W21 |

| Properties | Regular nonconvex |

(55)/2 (Vertex figure) |

Small stellated dodecahedron (dual polyhedron) |

.stl.png.webp)

In geometry, the great dodecahedron is a Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron, with Schläfli symbol {5,5/2} and Coxeter–Dynkin diagram of ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . It is one of four nonconvex regular polyhedra. It is composed of 12 pentagonal faces (six pairs of parallel pentagons), intersecting each other making a pentagrammic path, with five pentagons meeting at each vertex.

. It is one of four nonconvex regular polyhedra. It is composed of 12 pentagonal faces (six pairs of parallel pentagons), intersecting each other making a pentagrammic path, with five pentagons meeting at each vertex.

The discovery of the great dodecahedron is sometimes credited to Louis Poinsot in 1810, though there is a drawing of something very similar to a great dodecahedron in the 1568 book Perspectiva Corporum Regularium by Wenzel Jamnitzer.

The great dodecahedron can be constructed analogously to the pentagram, its two-dimensional analogue, via the extension of the (n – 1)-pentagonal polytope faces of the core n-polytope (pentagons for the great dodecahedron, and line segments for the pentagram) until the figure again closes.

Images

| Transparent model | Spherical tiling |

|---|---|

(With animation) |

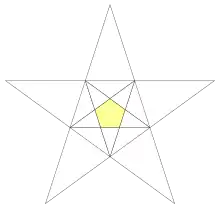

This polyhedron represents a spherical tiling with a density of 3. (One spherical pentagon face is shown above in yellow) |

| Net | Stellation |

× 20 × 20Net for surface geometry; twenty isosceles triangular pyramids, arranged like the faces of an icosahedron |

It can also be constructed as the second of three stellations of the dodecahedron, and referenced as Wenninger model [W21]. |

Related polyhedra

It shares the same edge arrangement as the convex regular icosahedron; the compound with both is the small complex icosidodecahedron.

If only the visible surface is considered, it has the same topology as a triakis icosahedron with concave pyramids rather than convex ones. The excavated dodecahedron can be seen as the same process applied to a regular dodecahedron, although this result is not regular.

A truncation process applied to the great dodecahedron produces a series of nonconvex uniform polyhedra. Truncating edges down to points produces the dodecadodecahedron as a rectified great dodecahedron. The process completes as a birectification, reducing the original faces down to points, and producing the small stellated dodecahedron.

| Stellations of the dodecahedron | ||||||

| Platonic solid | Kepler–Poinsot solids | |||||

| Dodecahedron | Small stellated dodecahedron | Great dodecahedron | Great stellated dodecahedron | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

| |||

| Name | Small stellated dodecahedron | Dodecadodecahedron | Truncated great dodecahedron |

Great dodecahedron |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagram |

||||

| Picture |  |

|

|

|

Usage

- This shape was the basis for the Rubik's Cube-like Alexander's Star puzzle.

- The great dodecahedron provides an easy mnemonic for the binary Golay code[1]

See also

References

- ↑

- Baez, John "Golay code," Visual Insight, December 1, 2015.