The set of large ornate staircases in the first-class section of the Titanic, and RMS Olympic ; sometimes collectively referred to as the Grand Staircase, is one of the most recognizable features of the British transatlantic ocean liner which sank on her maiden voyage in 1912 after a collision with an iceberg. Reflecting and reinforcing the staircase's iconic status is its frequent, and prominent, portrayal in media.

Historical descriptions

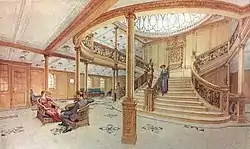

The "Main Staircase" is described as follows in the "Olympic" / & "Titanic" / Largest Steamers in the World (1911), White Star Line publicity brochure with coloured illustrations:

We leave the deck and pass through one of the doors which admit us to the interior of the vessel, and, as if by magic, we at once lose feeling that we are on board a ship, and seem instead to be entering the hall of some great house on shore. Dignified and simple oak panelling covers the walls, enriched in a few places by a bit of elaborate carved work, reminiscent of the days when Grinling Gibbons collaborated with his great contemporary, Wren.

In the middle of the hall rises a gracefully curving staircase, its balustrade supported by light scrollwork of iron with occasional touches of bronze, in the form of flowers and foliage. Above all a great dome of iron and glass throws a flood of light down the stairway, and on the landing beneath it a great carved panel gives its note of richness to the otherwise plain and massive construction of the wall. The panel contains a clock, on either side of which is a female figure, the whole symbolizing Honour and Glory crowning Time. Looking over the balustrade, we see the stairs descending to many floors below, and on turning aside we find we may be spared the labour of mounting or descending by entering one of the smoothly-gliding elevators which bear us quickly to any other of the numerous floors of the ship we may wish to visit.

The staircase is one of the principal features of the ship, and will be greatly admired as being, without doubt, the finest piece of workmanship of its kind afloat.[1]

In another promotional brochure by the White Star Line with black and white illustrations, The World's Largest & Finest Steamers / New Triple Screw / S.S."Olympic" and "Titanic" (1911), the following description is found:

A STRIKING INTRODUCTION to the wonders and beauty of these vessels is the Entrance Hall and Grand Staircase in the forward section where one begins to realize for the first time the magnificence of these surpassing steamers. The Grand Staircase, sixteen feet wide, extends over sixty feet and serves seven decks, five of which are also reached by the Three Electric Passenger Elevators. It is modeled closely after the style so prevalent during the reign of William and Mary, except that instead of the usual heavily-carved balustrade, a light wrought-iron grille has been employed, a fashion found in a few of the most exclusive great houses of that period. The Entrance Hall and Grand Staircase are surmounted by a glass dome of great splendor, a fitting crown as it were to these the largest and finest steamers in all the world.[2]

Location

Sited in the forward part of the ship, the Grand Staircase was the main connection between decks for first-class passengers and the point of entry to numerous public rooms. It descended in seven levels between the Boat Deck and E-Deck. Just forward of the staircase a passenger could turn the corner and find the three first-class elevators that connected alongside the staircase between A and E-Decks.

Boat Deck

The Boat Deck level of the stairwell functioned as an interior balcony overlooking the staircase and A-Deck below. From one end of the room to another the dimensions were 56 feet (17 m) wide by 33 feet (10 m) long.[3] There were two entry vestibules, 5 by 6 feet (1.5 m × 1.8 m), on either side of the Boat Deck that communicated with the outside. The gymnasium entrance was right next to the starboard Grand Staircase entrance. The officer's quarters and Marconi room were also accessible via two corridors that branched forward from either side of the staircase. This level was lined with arched windows that provided ample natural light to the stairwell during the day.

A-Deck

Off of the A-Deck level a long aft companionway ran along the starboard side, connecting passengers to the reading and writing room and the lounge at the far end, which was entered via revolving doors. Two entry vestibules, 5 by 6 feet (1.5 m × 1.8 m), connected passengers to the Promenade Deck and two corridors forward of the stairwell accessed the A-Deck first-class staterooms. A framed map of the North Atlantic route where Titanic's progress was updated every day at noon was most likely located on the port or starboard side of the room.[4]

B-Deck

Just off the B-Deck level staircase were the two "Millionaire's Suites", as well as two enclosed first-class entry foyers along each side. The bulk of B-Deck was occupied by first-class cabins, the finest and largest offered.

C-Deck

On C-Deck were the purser's and enquiry offices, just off the staircase on the starboard side. Passengers could store their valuables with the purser and submit Marconi messages sent via pneumatic tube to the Marconi room. They could also purchase small items like postcards, pay for tickets to the Turkish baths and squash court, reserve deck chairs, check out board games, and request their seating in the dining saloon, among other services. Long companionways branched off of the staircase forward and aft containing first-class staterooms, much like B-Deck above.

D-Deck

The D-Deck staircase opened directly onto the reception room and adjoining Dining Saloon. Behind the staircase were two arched entry vestibules and the companionways which communicated with first-class staterooms in the forward part of the ship.

E-Deck

On E-Deck the staircase narrowed and lost its grand sweeping curve, though it was designed in the same oak and wrought iron style. There were no public rooms on this deck, only first-class cabins. A modest single flight terminated on F-Deck, where the Turkish Baths and Swimming Pool could be reached.

Style and decor

The forward Grand Staircase was the pièce de resistance of the Titanic's first-class public rooms.[5] The two-storey-high A-Deck level featured a large wrought iron and glass dome overhead that allowed natural light to enter the stairwell during the day. The dome was fringed with a delicately molded plaster entablature and rested on the deck housing surrounding the stairwell. It was covered by a protective box to protect the dome from the elements and which also contained the lighting to illuminate the dome from behind in the evening. In the center of the dome hung a large crystal and gilt chandelier. The small beaded crystal chandelier fixtures identified on the wreck only hung in the forward parts of the A and Boat Deck levels, the rest contained cut-glass shades.

Each staircase was built of solid irish oak, with each banister containing elaborate wrought iron grilles with ormolu swags in the Louis XIV style. The staircases were 20 ft. wide and projected 17 ft. from the bulkhead. The surrounding entrance halls were appointed in the same polished oak paneling carved in the Neoclassical William & Mary style. The panels of the newel posts were carved with high relief garlands, each one of unique design, and topped by pineapple finials. Just behind the staircase were three elevator shafts that provided passengers access from their staterooms to the promenade deck. The floors were laid with cream-colored linoleum ("lino") tiles interspersed with black medallions. Armchairs and sofas upholstered in blue were provided just off the staircases and potted palms in raised holders dotted each level. On the Boat Deck level was an upright piano allowing the ship's orchestra to hold impromptu concerts in the stairwell.

.jpg.webp)

On the central landing of the A-Deck staircase was a clock flanked by two carved allegorical figures symbolizing "Honour and Glory crowning Time". A bronze cherub sculpture, holding an illuminated torch, graced the central newel post at the base of this staircase. There were likely smaller replica cherubs which graced either end of the B and C-Deck levels. On the D-Deck level, as the staircase opened onto the reception room, the central post held a huge gilt candelabra with electric lighting.

The B, C, D and E-Deck central landings all contained landscape and still-life oil paintings instead of the Honour and Glory crowning Time clock. These were probably painted by a Belfast artist on commission to Harland and Wolff.

Honour and Glory crowning Time clock

Honour and Glory crowning Time was the name given to the allegorical wall clock in the Neoclassical eclectic style located above the first central landing (from the top) of the Grand Staircase, just below the wrought iron and glass dome. It was one of a series of slave clocks in the ship.

Like the Olympic, Titanic was equipped with a large number of clocks supplied by the Magneta Company of Zurich (Switzerland), that were distributed throughout the transatlantic in passenger and crew spaces. These clocks, 48 in total, were controlled by two master clocks that were located in the chart room just behind the wheelhouse. Each master clock was capable of controlling 25 slave units in such a way that whenever the master clock advanced by one minute of time, the slave units that were connected to it would also advance by one minute of time, all in one synchronous operation.[6]

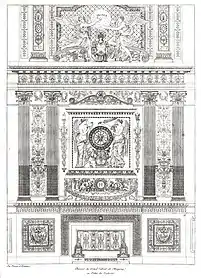

The ornamented oak panel comprised a half-point arch supported by two pilasters in composite order, each capital decorated with a winged putti's head in its centre. As a curiosity, the four volutes, two for each capital, were carved reversed. In the central panel, the round case of the clock itself rested upon an estipite adorned with laurel festoons, this was flanked by two winged female figures in mid-relief dressed with a chiton. From the onlooker's point of view, the figure at left represented Honour whereas the one at right depicted Glory. As accompanying attributes, Honour held a tablet in her left hand while the other was writing using a stylus, her left foot rested on top of a terrestrial globe. The personification of Glory had a palm branch in her right hand and next to her right foot was seen a laurel wreath in a vertical position leant against the aforesaid estipite. Surrounding the figural central panel there were different decorative motifs such as swags of fruits and flowers, egg-and-dart, scrolls, acanthus, rosettes, a pair of seated griffins, etc.

The main source of inspiration for Olympic's only architectural clock was a monumental chimney designed by Percier and Fontaine for Napoleon Bonaparte, which included a decorative timepiece. The relief clock in the Empire style was sculpted in white marble by Auguste-Marie Taunay, it represented History writing under the dictation of Victory. In 1810 the ensemble was installed in the Grand Office of Louis XIV in the now missing Tuileries Palace.[7] This palace was intentionally burned down in 1871 and ultimately demolished in 1883. Old photos of the timepiece exist and was partially depicted in the 1865 painting "Louis Visconti presenting the new plans for the Louvre to Napoleon III" by Jean-Baptiste-Ange Tissier. It was probably from the detailed drawing of the monumental chimney, first published in 1812 in the book by Percier and Fontaine Recueil de décorations intérieures,[8] that inspiration was drawn.

Among the several differences between Percier and Fontaine's original design and Olympic reinterpretation is that in the latter the two female figures were completely dressed, as opposed to the French ones, whose bodies' upper halves are shown almost entirely nude. The laurel wreath appeared on the floor in the Titanic's clock, whereas in the Napoleon's one the goddess Victory was holding it in her left hand. Likewise, many Greco-Roman military, warfare and victory symbology used in the original version to glorify Napoleon as the new "Roman" emperor, was not depicted in the British twin clocks.

According to the book, Titanic Voices: Memories from the Fateful Voyage:

Charles Wilson, who carved the central portion of the "Honour and Glory Crowning Time", remembered that when the Titanic finally set sail from Belfast there had not been time to set a clock into the ornate carved panel over her First-Class Staircase, and a mirror had to be substituted until the clock arrived.[9]

The ocean liner arrived from Belfast in Southampton at midnight, 3 April 1912. Therefore, the timepiece must have been installed sometime during the week before her maiden voyage on 10 April 1912.

The clock became popular due to its prominent portrayal in the 1997 blockbuster Titanic. After that, replicas can be seen in museums devoted to the ill-fated vessel, temporary exhibitions or marketed in different sizes and materials.

Aft grand staircase

There was a second grand staircase located further aft in the ship, between the third and fourth funnels. Although it was in the same style with a dome at the center, it was of much smaller proportions and only installed between A, B, and C Decks. A simple clock graced the main landing in contrast to the ornate Honour and Glory Crowning Time clock in the forward Staircase. One could access the Smoking Room from the A-Deck landing, as well as the lounge forward of the landing via a companionway.

A reception area for patrons of the À La Carte Restaurant and Café Parisien decorated in white-painted Georgian paneling occupied the whole of the B-Deck foyer off the aft staircase. There were comfortable carpeted seating areas with rattan-woven chairs, sofas, and tables.

Condition in the wreck

When Robert Ballard discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985, he found only a gaping well in the place that the staircase had once occupied. The deck house that once formed the Boat Deck level of the stairway is collapsed and the huge void left by where the dome had once been sited offers a convenient entry for remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs). A pile of wreckage and twisted metal framework lies at the bottom of D-Deck, obscuring access to the lower decks.

Because each staircase was constructed individually and entirely from wood, it is assumed that the staircase either broke apart and floated out of the stairwell during the sinking or disintegrated in the 73 years before the Titanic's rediscovery. Another option is that whatever remained of the staircase was destroyed by the force of the bow hitting the sea floor and the huge hydraulic blast which resulted. Survivors described a large wave that swept the Boat Deck as the Titanic took her final plunge – this, or the wave produced by the collapse of the forward funnel, is often blamed for smashing through the dome and destroying the Grand Staircase. The surrounding foyers, with their oak pillars, plaster ceilings with oak beams, and chandelier ceiling fixtures all survive in recognizable condition.[10]

During filming of sinking scenes for the 1997 film Titanic, the staircase set was wrenched from its steel-reinforced foundation by the force of the flooding. Director James Cameron commented:

Our staircase broke free and floated to the surface. It's likely that this is exactly what happened during the actual sinking, which would explain why there isn't much of the staircase left in the wreck … The matching physiques serve as a form of 'proof of concept' in terms of our accuracy …[11]

The aft grand staircase was most likely torn apart as the Titanic broke up, being at or just aft of the point of rupture. Much of the wood and other debris found floating after the sinking is thought to have come from one of the aft staircases.

Artifacts from the Titanic and Olympic's staircases

There are no known photographs of the Titanic's staircase, but many survive of the Olympic's, which is presumed to have been similar. In 1990 a huge trove of woodwork from the Olympic was found in a barn in the North of England, much of it belonging to the Grand Staircase.[12] These pieces retained the avocado green color they had been painted in the 1932 refit, and included large amounts of wall paneling, carved newel posts, window frames, cornice-work, and doors. Portions of the oak banisters from the aft grand staircase grace the staircase of the White Swan Hotel in Alnwick, England.[13] The chandeliers which once hung from the ceilings of the staircase occasionally come up for auction – sixteen were auctioned from the Haltwhistle Paint Factory in 2004. This auction also included the Olympic's four landscape oil paintings from the B, C, D and E-Deck landings, along with the communicating doors from the two Boat-Deck entry vestibules.[14]

The carved clock of the Olympic, believed to be identical to the one on Titanic, is displayed at the SeaCity Museum in Southampton.[15][16] This clock was used as the model for the one in Cameron's film.

Wreckage from the Titanic's aft and forward Grand Staircases, recovered in the weeks after the sinking, can be seen at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. This includes an elaborately carved section of newel post from the aft staircase and pieces of oak handrail. There are also re-purposed items made from woodwork recovered from the Titanic, including a rolling pin and cribbage board, which very likely came from the Grand Staircase.[17] A bronze cherub and the base of the forward A-Deck cherub have been recovered from the debris floor over the years. Fragments of the wrought-iron dome from the aft grand staircase have also been identified in the debris field.[18] Ken Marschall attested to spotting at least 9 pieces of the wrought iron and gilt balustrades from the staircases in the debris field from the 1986 Woods Hole expedition, though no photographs have ever been taken.[19]

In popular culture

Of the many films which have been made about the sinking of Titanic, almost all have depicted the Grand Staircase in one form or another. The staircase has come to symbolize the overall opulence and grandeur of the Titanic.

- In the 1943 film, the Grand Staircase landing is shown as a metaphor for the avarice of the British and American upper classes.

- Jean Negulesco's 1953 film has a number of scenes set on the Grand Staircase, though it bears only a superficial resemblance to the real one.

- Roy Ward Baker's 1958 film A Night to Remember also features scenes on the Grand Staircase, with recreations of the A and D Deck levels. The sets were based on archival photographs of the Olympic, lending them a general appearance of authenticity.

- In the 1979 docudrama S.O.S. Titanic actress Renee Harris, wife of producer Henry B. Harris, is shown stumbling on the steps and breaking her arm. This event took place in real life on the Titanic. However the staircase used was one from a mansion in London's Belgrave Square; it bore no relation to the appearance of the one on Titanic.[20]

- Raise the Titanic (1980) features a version of the A-Deck Grand Staircase after the wreck is raised by the salvagers. Because it was filmed before the discovery of the actual wreck, it wrongly depicts the Grand Staircase as fully intact, to the point that the glass dome and bronze cherub are still in place. It also wrongly places the staircase at the end of a grand pillared gallery (there was no such feature on Titanic).

- The 1996 CBS miniseries Titanic features a recreation of the Grand Staircase, though it wrongly locates the A-Deck level, with its distinctive clock and cherub light fixture, opening directly onto the D-Deck dining saloon. It also eliminates the glass dome and the entire reception room.

- The staircase was a major focal point in James Cameron's 1997 film as well. The forward Grand Staircase, decks A through D, were accurately built to the correct proportions, although the model that was used was 30% larger than the actual staircase. It was reinforced with a steel frame, as opposed to Titanic's made entirely in oak. The main body of the original grand staircase possessed twelve steps including the step landing below the clock. The film's replica had thirteen steps. Artisans from Mexico and Britain were hired to produce the opulent oak carvings and plaster-work, although some of the newel panels were plaster casts painted to look like wood, to save money and work. The 'Honour and Glory' clock was a major focal-point in the film - it was carved by master-sculptor Dave Coldham after the actual one from Olympic.[21]

- The staircases are also depicted in the video game Titanic: Adventure Out of Time. The fore grand staircase is depicted correctly for the most part, aside from some inaccuracies in the D and E deck landings, but in the aft grand staircase there is no clock present on the A-Deck landing. The oil paintings are also not shown.

- There are also several Titanic museums that have detailed replicas of the grand staircase. The ones featured at the Titanic museums in Branson, Missouri and Pigeon Forge, Tennessee were built using the ship's original deck plans but each differs from the original by featuring brass hand rails below the original handrails (for guest safety). The one at Titanic Belfast was again forced to make some rather big changes to accommodate current regulations.[22]

- The stationary full-scale Titanic replica that was (2017–2021) under construction in Sichuan was expected to include a recreation of the Grand Staircase.

See also

References

- ↑ The Titanic Pocket Book: A Passenger's Guide. John Blake, 2011

- ↑ GG Archives. Titanic Images - White Star Line Brochure Olympic & Titanic (1911)

- ↑ Beveridge 2009, p. 202

- ↑ Beveridge 2009, p. 236

- ↑ Titanic deckplans from the Encyclopedia Titanica. Accessed 22 April 2007.

- ↑ Titanic's Master of Time by Samuel Halpern

- ↑ Palais des Tuileries, Salon de Louis XIV photo

- ↑ Recueil de décorations intérieures by Percier and Fontaine (1812)

- ↑ What Does It Mean? by Alan St. George

- ↑ Lynch, Don & Marschall, Ken, Ghosts of the Abyss. 2001; 66-9.

- ↑ Cameron & Marsh 1997, p. 141

- ↑ Il Fantasma dell'Opera. "Titanic & Olympic: all the pictures you can find on the Web. Part 4/6". Archived from the original on 13 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Olympic's Fittings at White Swan Hotel, Alnwick, England Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 15 February 2008.

- ↑ "North Atlantic Run - RMS Olympic Haltwhistle Auction". www.northatlanticrun.com.

- ↑ http://www.rmsolympic.org/grand.html

- ↑ "Olympic - White Star Moments". Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ "Titanic in Nova Scotia ~ Museum Artifacts". novascotia.ca.

- ↑ "Web Hosting, Reseller Hosting & Domain Names from Heart Internet". titanic-titanic.com.

- ↑ Marschall 2001, p. 3

- ↑ "S.O.S. Titanic Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ↑ Ed W. Marsh (1997). James Cameron's Titanic. p. 34.

- ↑ "Gates and Railings by BMC Engineering Northern Ireland". BMC Engineering.

Bibliography

- Beveridge, Bruce (2009). The Ship Magnificent, Volume Two: Interior Design & Fitting. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4626-4.

- Cameron, James; Marsh, Ed (1997). James Cameron's Titanic. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-649060-3.

- Lynch, Don; Marschall, Ken (2003). Ghosts of the Abyss. Madison Press Books. ISBN 0-306-81223-1.

- Marschall, Ken (2001). James Cameron's Titanic Expedition: What We Saw on and Inside the Wreck. marconigraph.com.