George Rolleston | |

|---|---|

George Rolleston. | |

| Born | 30 July 1829 Maltby Hall, England |

| Died | 16 July 1881 (aged 51) |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Linacre Professor of Anatomy and Physiology University of Oxford |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Zoology |

George Rolleston MA MD FRCP FRS (30 July 1829 – 16 June 1881) was an English physician and zoologist. He was the first Linacre Professor of Anatomy and Physiology to be appointed at the University of Oxford, a post he held from 1860 until his death in 1881. Rolleston, a friend and protégé of Thomas Henry Huxley, was an evolutionary biologist.[1]

Life

Rolleston was born at Maltby Hall, near Rotherham, Yorkshire, England.[1] His parents were Rev. George Rolleston (rector and squire of Maltby) and Anne Nettleship; his brother, William Rolleston, became a prominent politician in New Zealand.[2]

Rolleston was educated at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Gainsborough;[3] Sheffield Collegiate School; Pembroke College, Oxford and St Bartholomew's Hospital, London. He qualified with the degrees of BA (1850, 1st Class), MA and MD. The same year he entered Pembroke College, Oxford, and took a First Class in Classics. After qualifying as a physician, Rolleston became a Fellow of Pembroke College in 1851, holding posts at the British Civil Hospital, Smyrna (during Crimean War), and Assistant Physician, Children's Hospital, London (1857). Gradually he became more interested in zoology, and spent the rest of his career as a zoologist, and on the human sciences. His research included comparative anatomy, physiology, zoology, archaeology and anthropology. In 1860, he was elected to the newly founded Linacre Professorship of Anatomy and Physiology, which he held to the time of his death. He became FRCP in 1859, was elected Fellow of the Royal Society on 5 June 1862, and Fellow of Merton College, Oxford, in 1872. He was a member of the Council of the Oxford University, its representative in the General Medical Council, and also an active member of the Oxford Local Board.[1]

In 1861, Rolleston married Grace, daughter of John Davy FRS and niece of Sir Humphry Davy; they had seven children.[1] Having suffered from kidney disease for over a year, he died of uremic convulsions in Oxford in 1881 and is buried with his wife, who died in 1914, in Holywell Cemetery there. He had gone to Italy and France to seek treatment but returned to England a week prior to his death after his condition did not improve and finding out that Grace was seriously ill.[4] In Who Do You Think You Are?, his great-grandson Frank Gardner, while researching on why his grandfather John Rolleston (George's son) was so reticent about his childhood, discovered that Grace suffered from a mental breakdown after her husband's death and was committed to Warneford and Chiswick asylums and that a thirteen-year-old John had witnessed one of his mother's breakdowns.

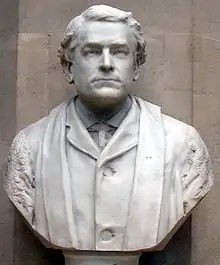

Rolleston's anthropological archive is now in the Ashmolean Museum, along with the archaeological material resulting from his excavations. A bust of him sits in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

One of his sons was Sir Humphry Rolleston, an eminent physician himself. His great grandson is the BBC journalist Frank Gardner.[5]

Career

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

As a zoologist, Rolleston was a protégé of Thomas Henry Huxley, and took part in both of the critical sessions at the 1860 British Association meeting in Oxford.[6] Rolleston was one of the organisers for the meeting: he arranged for Huxley to stay at Christ Church during the meeting, and to have a crocodile skull in Huxley's room for study. Huxley was instrumental in Rolleston's appointment to the Linacre chair that very year, backing him against Owen's candidate. Rolleston wrote him a 'you'll never regret this' letter.[7]

As an expert on the brain, Rolleston was present on the Thursday, when Huxley denied Owen's claim that the human brain had parts that apes did not, and again on the Saturday for the debate on Darwin, where his opponent was Bishop Samuel Wilberforce. Rolleston was an Anglican, but a liberal in his religious beliefs, as was Huxley's other supporter in the brain debate, William Henry Flower. Huxley organised his FRS, as he did for Flower; and the two men acted as liaison between the X-Club and the Royal Society.[8] Rolleston remarked later that whenever he lectured on evolution, he was asked 'Was I an atheist or a Unitarian?' and some of Huxley's attacks on the Old Testament did cause him anguish.[9][10]

Rolleston was so identified with Huxley at this time that he appeared as one of 'Tom Huxley's low set' in the ironical skit Report of a sad case recently tried before the Lord Mayor, Owen versus Huxley (publ. George Pycraft 1863) as 'Charlie Darwin the pigeon-fancier and Rollstone' cheer on their barrow-boy. This vivid broadsheet was certainly well informed: it mentions Owen's disgraceful maltreatment of Gideon Mantell. He was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1869.[11]

See also

Publications

- 1870. Forms of animal life: a manual of comparative anatomy. Oxford.

- 1888. Scientific papers and addresses. 2 vols, Oxford.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 "Obituary Notices of Fellows Deceased". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 33 (216–219): i–xxvii. 1881. doi:10.1098/rspl.1881.0061. S2CID 186211012.

- ↑ "The Hon. William Rolleston". The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : Canterbury Provincial District. Christchurch: The Cyclopedia Company Limited. 1903. p. 38.

- ↑ now Queen Elizabeth's High School, Gainsborough

- ↑ "BMJ Obituary — George Rolleston, M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.S. Physician to the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford". British Medical Journal. Transcribed by Pitt Rivers Museum. 25 June 1881. pp. 1028–9.

- ↑ "Frank Gardner". Who Do You Think You Are?. Season 12. Episode 7. 24 September 2015. BBC. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Desmond, pp. 274–6, 280–1

- ↑ Rolleston to Huxley, Huxley Papers (Imperial College), HP 25.142, 148, 150.

- ↑ Desmond, pp. 306, 329

- ↑ Rolleston to Huxley 1 Jan 1865 HP 25.167

- ↑ Desmond, pp. 331–2

- ↑ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

References

- Desmond, Adrian 1994. Huxley: vol 1 The Devil's Disciple, London: Michael Joseph ISBN 0-7181-3641-1

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Bulloch's Roll; DSB

External links

Works by or about George Rolleston at Wikisource

Works by or about George Rolleston at Wikisource