| Part of a series on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

Genetic studies on Serbs show close affinity to other neighboring South Slavs.[1]

Y-DNA

Y-chromosomal haplogroups identified among the Serbs from Serbia and near countries are the following with respective percentages: I2a (36.6[2]-42%[3]), E1b1b (16.5[3]-18.2%[2]), R1a (14.9[2]-15%[3]), R1b (5[2]-6%[3]), I1 (1.5[3]-7.6%[2]), J2b (4.5[3]-4.9%[2]), J2a (4[4]-4.5%[3]), J1 (1[4]-4.5%[3]), G2a (1.5[3]-5.8%[4]), and several other uncommon haplogroups with lesser frequencies.[3][5][6][7]

I2a-P37.2 is the most prevailing haplogroup, accounting for one-third of Serbians. It is represented by four sub-clusters I-PH908 (25.08%), I2a1b3-L621 (7.59%), I2-CTS10228 (3.63%) and I2-M223 (0.33%).[2] A 2019 study of Serb samples from different parts of the Western Balkans showed that "approximately half of them originated from Herzegovina and Old Herzegovina" which population throughout history strongly influenced today's Serbian male genetics.[2] Older research considered that the high frequency of this subclade in the South Slavic-speaking populations to be the result of a "pre-Slavic" paleolithic settlement in the region, the research by O.M. Utevska (2017) confirmed that the haplogroup STR haplotypes have the highest diversity in Ukraine, with ancestral STR marker result "DYS448=20" comprising "Dnieper-Carpathian" cluster, while younger derived result "DYS448=19" comprising the "Balkan cluster" which is predominant among the South Slavs.[8] This "Balkan cluster" also has the highest variance in Ukraine, which indicates that the very high frequency in the Western Balkan is because of a founder effect.[8] Utevska calculated that the STR cluster divergence and its secondary expansion from the middle reaches of the Dnieper river or from Eastern Carpathians towards the Balkan peninsula happened approximately 2,860 ± 730 years ago, relating it to the times before Slavs, but much after the decline of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture.[8] More specifically, the "Balkan cluster" is represented by a single SNP, I-PH908, known as I2a1a2b1a1a1c in ISOGG phylogenetic tree (2019), and according to YFull YTree it formed and had TMRCA approximately 1,850-1,700 YBP (2nd-3rd century AD).[9] Although I-L621 it is dominant among the modern Slavic peoples on the territory of the former Balkan provinces of the Roman Empire, until now it was not found among the samples from the Roman period and is almost absent in contemporary population of Italy.[10] It was found in the skeletal remains with artifacts, indicating leaders, of Hungarian conquerors of the Carpathian Basin from the 9th century, part of Western Eurasian-Slavic component of the Hungarians.[10] According to Pamjav et al. (2019) and Fóthi et al. (2020), the distribution of ancestral subclades like of I-CTS10228 among contemporary carriers indicates a rapid expansion from Southeastern Poland, is mainly related to the Slavs and their medieval migration, and the "largest demographic explosion occurred in the Balkans".[10][11]

E1b1b-M215 is the second most prevailing haplogroup amongst Serbs, accounting for nearly one-fifth of Serbians. It is represented by four sub-clusters E-V13 (17.49%), E1b1b-V22 (0.33%), and E1b1b-M123 (0.33%).[2] In Southeast Europe, its frequency peaks at the southeastern edge of the region and its variance peaks in the region's southwest. Although its frequency is very high in Kosovar Albanians (46%) and Macedonian Romani (30%), this phenomenon is of a focal rather than a clinal nature, most likely being a consequence of genetic drift.[5] E-V13 is also high amongst Albanians in North Macedonia (34%) and Albanians in Albania (24%), as well as ethnic Macedonians, Romanians, and Greeks. It is found at low to moderate frequencies in most Slavic populations. However, amongst South Slavs, it is quite common. It is found in 27% of Montenegrins, 22% of Macedonians, and 18% of Bulgarians, all Slavic peoples. Moderate frequencies of E-V13 are also found in Italy and western Anatolia.[5][7] In most of Central Europe (Hungary, Austria, Switzerland, Ukraine, Slovakia), it is found at low to moderate frequencies of 7-10%, in both R1a (Slavic) and R1b (Germanic/Celtic) dominated populations. It likely originated in the Balkans, Greece, or the Carpathian Basin 9000 YBP or shortly before its arrival in Europe during the Neolithic. Its ancestral haplogroup, E1b1b1a-M78, is of northeast African origin.[7]

R1a1-M17 accounts for about one-seventh to one-sixth of Serbian Y-chromosomes. It is represented by four sub-clusters R1a (10.89%), R1a-M458 (2.31%), R1a-YP4278 (1.32%), and R1a-Y2613 (0.33%).[2] Its frequency peaks in Ukraine (54.0%).[5] It is the most predominant haplogroup in the general Slavic paternal gene pool. The variance of R1a1 in the Balkans might have been enhanced by infiltrations of Indo-European speaking peoples between 2000 and 1000 BC, and by the Slavic migrations to the region in the early Middle Ages.[5][6] A descendant lineage of R1a1-M17, R1a1a7-M458, has the highest frequency in Central and Southern Poland.[12]

R1b1b2-M269 is moderately represented among Serbian males (6–10%), 10% in Serbia (Balaresque et al. 2010),[13] with subclade M269* (xL23) 4.4% in Serbia, 5.1% in Macedonia, 7.9% in Kosovo. The highest frequency in the central Balkans (Myres et al. 2010).[14] It has its frequency peak in Western Europe (90% in Wales), but a high frequency is also found in Central Europe among the West Slavs (Poles, Czechs, Slovaks) and Hungarians as well as in the Caucasus among the Ossetians (43%).[5] It was introduced to Europe by farmers migrating from western Anatolia, probably about 7500 YBP. Serb bearers of this haplogroup are in the same cluster as Central and East European ones, as indicated by the frequency distributions of its sub-haplogroups with respect to total R-M269. The other two clusters comprise, respectively, West Europeans and a group of populations from Greece, Turkey, the Caucasus and the Circum-Uralic region.[14]

J2b-M102 and J2a1b1-M92 have low frequencies among the Serbs (6–9% combined). Various other lineages of haplogroup J2-M172 are found throughout the Balkans, all with low frequencies. Haplogroup J and all its descendants originated in the Middle East. It is proposed that the Balkan Mesolithic foragers, bearers of I-P37.2 and E-V13, adopted farming from the initial J2 agriculturalists who colonized the region about 7000 to 8000 YBP, transmitting the Neolithic cultural package.[7]

I1-M253 is also found in low frequencies (1.5-7.6%) and is represented by three sub-clusters I1-P109 (5.28%), I1 (1.32%), and I1-Z63 (0.99%).[2]

An analysis of molecular variance based on Y-chromosomal STRs showed that Slavs can be divided into two groups: one encompassing West Slavs, East Slavs, Slovenes, and western Croats, and the other – all remaining Southern Slavs. Croats from northern Croatia (Zagreb region) fell into the second group. This distinction could be explained by a genetic contribution of pre-Slavic Balkan populations to the genetic heritage of some South Slavs belonging to the group.[15] Principal component analysis of Y-chromosomal haplogroup frequencies among the three ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnian Serbs, Bosnian Croats, and Bosniaks), showed that Bosnian Serbs and Bosniaks are genetically closer to each other than either of them is to Bosnian Croats (mainly due to Bosnian Croats very high I2a frequency).[6] According to correspondence analysis, admixture analysis and Rst genetic distance, Serbian regional population samples cluster together and are closest to Montenegrins, Macedonians and Bulgarians, with Western Serbians being an intermediate between them and Croatian-Bosnian and Herzegovinian cluster.[16][17] According to 2022 study on 1200 samples from Serbia, Old Herzegovina, Kosovo and Metohija, "genetic distances between three groups of samples, evaluated by the Fst and Rst statistical values, and further visualized through multidimensional scaling plot, showed great genetic similarity between datasets from Old Herzegovina and present-day Serbia. Genetic difference in the haplogroup distribution and frequency between datasets from historical region of Old Herzegovina and from geographical region of Kosovo and Metohija was confirmed with highest Fst and Rst vaules".[18]

Y-DNA Haplogroup frequencies

| geographical association of the haplogroup: | Eastern Europe & the Balkans | West European | Mediterranean & Near Eastern | East Asian & Siberian | South Asian | other/undetermined | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Samples | Source | I2 | R1a | E | I1 | R1b | J1 | J2a | J2b | G | T | L | N | Q | C | H | other/undetermined |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina; ethnic Serbs | 95 | Marjanović et al. (2005),[19] Battaglia et al. (2008),[20] Kovačević et al. (2014)[21][22] | 40.00 | 14.70 | 22.10 | 2.10 | 5.20 | 1.10 | 2.10 | 5.20 | 2.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Old Herzegovina ( Herzegovina and Northwestern Montenegro; ethnic Serbs) | 400 | Mihajlovic et. al (2022)[18] | 45.83 | 13.00 | 12.0 | 6.97 | 4.8 | 7.50 | 2.30 | 2.00 | 5.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Western Serbia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prijepolje, Ub; ethnic Serbs | 67 | Todorović et al. (2015)[23] | 40.30 | 13.43 | 4.48 | 23.88 | 2.99 | 0.00 | 1.49 | 2.99 | 2.99 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.46 |

| Western Serbia;[24] general population | 237 | Stevanović et al. (2007)[25][26] | 43.46 | 10.13 | 13.50 | 7.17 | 10.13 | 1.69 | 3.38 | 2.53 | 1.27 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 2.53 | 1.69 | 1.69 | 0.42 | 0.00 |

| Central and Eastern Serbia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Central Serbia;[27] general population | 179 | Mirabal et al. (2010)[28][29] | 37.43 | 13.96 | 17.31 | 7.26 | 4.46 | 0.55 | 3.35 | 1.67 | 2.23 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 3.35 | 1.67 | 0.00 | 2.23 | 0.00 |

| Aleksandrovac county; ethnic Serbs | 85 | Todorović et al. (2014)[30] | 35.29 | 21.17 | 15.29 | 4.70 | 1.17 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 4.70 | 10.58 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.17 |

| Central Serbia; general population | 71 | Zgonjanin et al. (2017)[31] | 33.80 | 16.90 | 16.90 | 11.27 | 5.63 | 2.82 | 4.23 | 2.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.41 | 2.82 | 0.00 | 1.41 | 0.00 |

| Belgrade; general population | 113 | Peričić et al. (2005),[32] Kushniarevich et al. (2015)[33][34] | 31.86 | 15.93 | 21.24 | 5.31 | 10.62 | 0.00 | 2.65 | 5.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 3.54 |

| Central Serbia;[27] general population | 103 | Regueiro et al. (2012)[35] | 30.10 | 20.40 | 18.50 | 7.80 | 7.70 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.90 | 5.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.90 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Southern and Southeastern Serbia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kosovo; ethnic Serbs | 400 | Mihajlovic et. al (2022)[18] | 35.31 | 12.70 | 23.2 | 4.19 | 8.70 | 11.50 | 2.20 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.00 | |||

| Southern Serbia; general population | 69 | Zgonjanin et al. (2017)[31] | 31.88 | 13.04 | 28.99 | 7.25 | 2.90 | 4.35 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.90 | 2.90 | 0.00 | 1.45 | 0.00 |

| Niš; general population | 38 | Scorrano et al. (2017)[3] | 28.95 | 18.42 | 13.16 | 2.63 | 10.53 | 7.89 | 5.26 | 7.89 | 2.63 | 2.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Vojvodina | ||||||||||||||||||

| Novi sad; general population | 185 | Veselinović et al. (2008)[36][26] | 32.43 | 15.14 | 15.68 | 6.49 | 10.27 | 1.08 | 3.78 | 7.57 | 1.62 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 1.62 | 0.54 | 2.70 | 0.00 |

| Vojvodina; general population | 69 | Zgonjanin et al. (2017)[31] | 30.43 | 18.84 | 21.74 | 4.35 | 5.80 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 4.35 | 4.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Multiple regions | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serbia; ethnic Serbs | 400 | Mihajlovic et. al (2022)[18] | 39.24 | 13.8 | 14.50 | 9.56 | 5.50 | 10.8 | 1.80 | 0.50 | 3.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.80 | ||||

| Serbia (North, Central, South); general population | 209 | Zgonjanin et al. (2017)[31] | 32.05 | 16.27 | 22.49 | 7.66 | 4.78 | 2.87 | 2.39 | 2.87 | 1.91 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.83 | 1.92 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.00 |

| Serbia (Niš, Brestovac, Studenica, Šumadija); general population | 67 | Scorrano et al. (2017)[3] | 41.79 | 14.93 | 16.42 | 1.49 | 5.97 | 4.48 | 4.48 | 4.48 | 1.49 | 4.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Serbia, Montenegro, B&H, Croatia; ethnic Serbs | 303 | Kačar et al. (2019)[2] | 36.63 | 14.85 | 18.15 | 7.59 | 4.95 | 2.64 | 3.30 | 4.95 | 1.98 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 3.96 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Prijepolje, Belgrade, Ub; general population | 96 | Todorović et al. (2015)[23] | 33.33 | 12.50 | 7.29 | 19.79 | 10.41 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 3.12 | 2.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.08 | 0.00 | 2.08 | 1.04 | 5.20 |

The dominant recent origin of the population of wider Central Serbia: pink, green and gray-blue – areas settled from the Dinaric Alps (mostly Old Herzegovina), Kosovo, and Romania, respectively. Dark red, yellow and dark blue: natives of Šopluk and Torlak, the South Morava Valley, and Eastern Serbia, respectively, and settlers from these areas (mostly in Central Serbia). Light red-oases of natives of Western and Central Serbia. Black dots – returnees from Vojvodina.

The dominant recent origin of the population of wider Central Serbia: pink, green and gray-blue – areas settled from the Dinaric Alps (mostly Old Herzegovina), Kosovo, and Romania, respectively. Dark red, yellow and dark blue: natives of Šopluk and Torlak, the South Morava Valley, and Eastern Serbia, respectively, and settlers from these areas (mostly in Central Serbia). Light red-oases of natives of Western and Central Serbia. Black dots – returnees from Vojvodina. Geographical regions of Serbia-detailed

Geographical regions of Serbia-detailed

mtDNA

According to Davidovic et al. (2014) study of Mitochondrial DNA in 139 samples in Serbia are present "mtDNA lineages predominantly found within the Slavic gene pool (U4a2a*, U4a2a1, U4a2c, U4a2g, HV10), supporting a common Slavic origin, but also lineages that may have originated within the southern Europe (H5*, H5e1, H5a1v) and the Balkan Peninsula in particular (H6a2b and L2a1k)".[37] According to 2017 study on haplogroup U diversity "putative Balkan-specific lineages (e.g. U1a1c2, U4c1b1, U5b3j, K1a4l and K1a13a1) and lineages shared among Serbians (South Slavs) and West and East Slavs were detected (e.g. U2e1b1, U2e2a1d, U4a2a, U4a2c, U4a2g1, U4d2b and U5b1a1). The exceptional diversity of maternal lineages found in Serbians may be associated with the genetic impact of both autochthonous pre-Slavic Balkan populations whose mtDNA gene pool was affected by migrations of various populations over time (e.g. Bronze Age pastoralists) and Slavic and Germanic newcomers in the early Middle Ages".[38] The 2020 study of 226 samples mitochondrial genome data of Serbian population "supported more pronounced genetic differentiation among Serbians and two Slavic populations (Russians and Poles) as well as expansion of the Serbian population after the Last Glacial Maximum and during the Migration period (fourth to ninth century A.D.)".[39]

Autosomal DNA

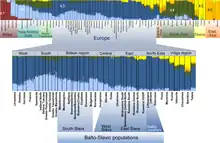

According to 2013 autosomal IBD survey "of recent genealogical ancestry over the past 3,000 years at a continental scale", the speakers of Serbo-Croatian language share a very high number of common ancestors dated to the migration period approximately 1,500 years ago with Poland and Romania-Bulgaria cluster among others in Eastern Europe. It is concluded to be caused by the Hunnic and Slavic expansion, which was a "relatively small population that expanded over a large geographic area", particularly "the expansion of the Slavic populations into regions of low population density beginning in the sixth century" and that it is "highly coincident with the modern distribution of Slavic languages".[40] The 2015 IBD analysis found that the South Slavs have lower proximity to Greeks than with East Slavs and West Slavs, and "even patterns of IBD sharing among East-West Slavs–'inter-Slavic' populations (Hungarians, Romanians and Gagauz)–and South Slavs, i.e. across an area of assumed historic movements of people including Slavs". The slight peak of shared IBD segments between South and East-West Slavs suggests a shared "Slavonic-time ancestry".[41] The 2014 IBD analysis comparison of Western Balkan and Middle Eastern populations found negligible gene flow between 16th and 19th century during the Islamization of the Balkans.[42]

According to a 2014 autosomal analysis of Western Balkan, the Serbian population shows genetic uniformity with other South Slavic populations, but the "Serbians and Montenegrins have an intermediate position on PCA plot and on Fst–based network among other Western Balkan populations".[42] In the 2015 analysis, Serbians were again in the middle of a Western South Slavic cluster (Croatians, Bosnians and Slovenians) and Eastern South Slavic cluster (Macedonians and Bulgarians). The western cluster has an inclination toward Hungarians, Czechs, and Slovaks, while the eastern cluster toward Romanians and some extent Greeks.[41] The studies also found very high correlation between genetic, geographic and linguistic distances of Balto-Slavic populations.[42][41] According to a 2020 autosomal marker analysis, Serbians are closest to Bosnians while the ethnically close Montenegrins are in-between them and Kosovo Albanians.[43]

According to 2023 archaeogenetic study autosomal qpAdm modelling, the modern-day Serbs from the Western Balkans are 58.4% of Central-Eastern European early medieval (mostly Slavic), 39.2% of Croatia-Serbia local Roman and 2.3% Imperial Era West Anatolian ancestry.[44]

A genetic study of Sorbs showed that they share greatest affinity with Poles, while the results of comparison to the Serbs and Montenegrins because of historical hypotheses of common origin showed that "the Sorbs were most different to Serbia and Montenegro, likely reflecting the considerable geographical distance between the two populations."[45]

Physical anthropology

According to Serbian physical anthropologist Živko Mikić, the medieval population of Serbia developed a phenotype that represented a mixture of Slavic and indigenous Balkan Dinaric traits. Mikić argues that the Dinaric traits, such as brachycephaly and a bigger average height, have been since then becoming predominant over the Slavic traits among Serbs.[46]

Gallery

Admixture analysis of autosomal SNPs in a global context on the resolution level of 7 assumed ancestral populations per Kovačević et al. (2014)

Admixture analysis of autosomal SNPs in a global context on the resolution level of 7 assumed ancestral populations per Kovačević et al. (2014) Principal component (PC) analysis of the variation of autosomal SNPs in Western Balkan populations in Eurasian context per Kovačević et al. (2014)

Principal component (PC) analysis of the variation of autosomal SNPs in Western Balkan populations in Eurasian context per Kovačević et al. (2014) Admixture analysis on the resolution level of 6 assumed ancestral populations per Kushniarevich et al. (2015)

Admixture analysis on the resolution level of 6 assumed ancestral populations per Kushniarevich et al. (2015) PC1vsPC2 plot based on whole genome SNP data per Kushniarevich et al. (2015)

PC1vsPC2 plot based on whole genome SNP data per Kushniarevich et al. (2015)

See also

References

- ↑ Novembre J, Johnson T, Bryc K, Kutalik Z, Boyko AR, Auton A, et al. (November 2008). "Genes mirror geography within Europe". Nature. 456 (7218): 98–101. Bibcode:2008Natur.456...98N. doi:10.1038/nature07331. PMC 2735096. PMID 18758442.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Kačar et al. 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scorrano et al. 2017.

- 1 2 3 Regueiro et al. 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Peričić et al. 2005

- 1 2 3 Marjanović et al. 2005

- 1 2 3 4 Battaglia et al. 2008

- 1 2 3 O.M. Utevska (2017). Генофонд українців за різними системами генетичних маркерів: походження і місце на європейському генетичному просторі [The gene pool of Ukrainians revealed by different systems of genetic markers: the origin and statement in Europe] (PhD) (in Ukrainian). National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. pp. 219–226, 302.

- ↑ "I-PH908 YTree v8.06.01". YFull.com. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 Fóthi E, Gonzalez A, Fehér T, Gugora A, Fóthi Á, Biró O, Keyser C (2020). "Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes". Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 12 (1). doi:10.1007/s12520-019-00996-0.

- ↑ Pamjav HM, Fehér T, Németh E, Csáji LK (2019). Genetika és őstörténet (in Hungarian). Napkút Kiadó. p. 58. ISBN 978-963-263-855-3.

The earliest common ancestor of the I2-CTS10228 (commonly known as the "Dinaric-Carpathian") subgroup dates back to 2,200 years ago, so it is not it is that the Mesolithic population in Eastern Europe has survived to such an extent, but that a small family of Mesolithic groups has successfully integrated into the European Iron Age in a society that was soon beginning to expand strongly. the spread of peoples, rather than families, and the spread of clans, and it is impossible to relate this to the current ethnic identity. Western Europe, on the other hand, is completely absent, with the exception of the East German-speaking areas of Slavic in the early Middle Ages.

- ↑ Underhill PA, Myres NM, Rootsi S, Metspalu M, Zhivotovsky LA, King RJ, et al. (April 2010). "Separating the post-Glacial coancestry of European and Asian Y chromosomes within haplogroup R1a". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (4): 479–484. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.194. PMC 2987245. PMID 19888303.

- ↑ Balaresque P, Bowden GR, Adams SM, Leung HY, King TE, Rosser ZH, et al. (January 2010). Penny D (ed.). "A predominantly neolithic origin for European paternal lineages". PLOS Biology. 8 (1): e1000285. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285. PMC 2799514. PMID 20087410.

- 1 2 Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, et al. (January 2011). "A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. PMC 3039512. PMID 20736979.

- ↑ Rębała K, Mikulich AI, Tsybovsky IS, Siváková D, Džupinková Z, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Szczerkowska Z (2007). "Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (5): 406–414. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0125-6. PMID 17364156.

- ↑ Mirabal et al. 2010, pp. 384–385.

- ↑ Scorrano et al. 2017, pp. 279–385.

- 1 2 3 4 Mihajlovic, Milica; Tanasic, Vanja; Markovic, Milica Keckarevic; Kecmanovic, Miljana; Keckarevic, Dusan (2022-11-01). "Distribution of Y-chromosome haplogroups in Serbian population groups originating from historically and geographically significant distinct parts of the Balkan Peninsula". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 61: 102767. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2022.102767. ISSN 1872-4973. PMID 36037736. S2CID 251658864.

- ↑ Marjanović et al. 2005.

- ↑ Battaglia et al. 2008.

- ↑ Kovacevic L, Tambets K, Ilumäe AM, Kushniarevich A, Yunusbayev B, Solnik A, et al. (2014-08-22). Paschou P (ed.). "Standing at the gateway to Europe--the genetic structure of Western balkan populations based on autosomal and haploid markers". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105090. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j5090K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105090. PMC 4141785. PMID 25148043.

- ↑ first published in Marjanović et al., the same samples retested in Battaglia et al., retested again and 14 additional samples added in Kovačević et al.

- 1 2 "Етнологија и генетика - Прелиминарна мултидисциплинарна истраживања порекла Срба и становништва Србије". СРПСКИ НАУЧНИ ЦЕНТАР. 2020-05-10. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ↑ used in Scorrano et al. as reference for Western Serbia

- ↑ Stevanović M, Dobricić V, Keckarević D, Perović A, Savić-Pavićević D, Keckarević-Marković M, et al. (September 2007). "Human Y-specific STR haplotypes in population of Serbia and Montenegro". Forensic Science International. 171 (2–3): 216–221. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.05.038. PMID 16806776.

- 1 2 predicted from STR haplotypes using Nevgen Genealogy Tools v1.2, desktop version

- 1 2 used in Scorrano et al. as reference for Central Serbia

- ↑ Mirabal et al. 2010.

- ↑ Šehović et al. 2018.

- ↑ Todorović et al. 2014a, p. 251.

- 1 2 3 4 Zgonjanin et al. 2017.

- ↑ Peričić et al. 2005.

- ↑ Kushniarevich A, Utevska O, Chuhryaeva M, Agdzhoyan A, Dibirova K, Uktveryte I, et al. (2015-09-02). Calafell F (ed.). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- ↑ first published in Peričić et al., retested in Kushniarevich et al.

- ↑ Todorović et al. 2014a, p. 259, citing Regueiro et al. 2012

- ↑ Veselinovic IS, Zgonjanin DM, Maletin MP, Stojkovic O, Djurendic-Brenesel M, Vukovic RM, Tasic MM (April 2008). "Allele frequencies and population data for 17 Y-chromosome STR loci in a Serbian population sample from Vojvodina province". Forensic Science International. 176 (2–3): e23–e28. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.04.003. PMID 17482396.

- ↑ Davidovic et al. 2015.

- ↑ Davidovic et al. 2017.

- ↑ Davidovic et al. 2020.

- ↑ Ralph P, Coop G (2013). "The geography of recent genetic ancestry across Europe". PLOS Biology. 11 (5): e1001555. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555. PMC 3646727. PMID 23667324.

- 1 2 3 Kushniarevich A, Utevska O, Chuhryaeva M, Agdzhoyan A, Dibirova K, Uktveryte I, et al. (2015). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- 1 2 3 Kovacevic L, Tambets K, Ilumäe AM, Kushniarevich A, Yunusbayev B, Solnik A, et al. (2014). "Standing at the gateway to Europe--the genetic structure of Western balkan populations based on autosomal and haploid markers". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105090. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j5090K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105090. PMC 4141785. PMID 25148043.

- ↑ Takic Miladinov, D; Vasiljevic, P; Sorgic, D; et al. (2020). "Allele frequencies and forensic parameters of 22 autosomal STR loci in a population of 983 individuals from Serbia and comparison with 24 other populations". Annals of Human Biology. 47 (7–8): 632–641. doi:10.1080/03014460.2020.1846784. PMID 33148044.

- ↑ Olalde, Iñigo; Carrión, Pablo (December 7, 2023). "A genetic history of the Balkans from Roman frontier to Slavic migrations". Cell. 186 (25): P5472-5485.E9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.10.018. PMC 10752003. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ↑ Veeramah KR, Tönjes A, Kovacs P, Gross A, Wegmann D, Geary P, et al. (September 2011). "Genetic variation in the Sorbs of eastern Germany in the context of broader European genetic diversity". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (9): 995–1001. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.65. PMC 3179365. PMID 21559053.

- ↑ Mikić Z (1994). "Beitrag zur Anthropologie der Slawen auf dem mittleren und westlichen Balkan". Balcanica". (Belgrade: The Institute for Balkan Studies of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts). 25: 99–109.

Sources

- Battaglia V, Fornarino S, Al-Zahery N, Olivieri A, Pala M, Myres NM, et al. (June 2009). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in Southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–830. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

- Bosch E, Calafell F, González-Neira A, Flaiz C, Mateu E, Scheil HG, et al. (July 2006). "Paternal and maternal lineages in the Balkans show a homogeneous landscape over linguistic barriers, except for the isolated Aromuns". Annals of Human Genetics. 70 (Pt 4): 459–487. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2005.00251.x. PMID 16759179. S2CID 23156886.

- Cvjetan S, Tolk HV, Lauc LB, Colak I, Dordević D, Efremovska L, et al. (June 2004). "Frequencies of mtDNA haplogroups in southeastern Europe--Croatians, Bosnians and Herzegovinians, Serbians, Macedonians and Macedonian Romani". Collegium Antropologicum. 28 (1): 193–198. PMID 15636075.

- Davidovic S, Malyarchuk B, Aleksic JM, Derenko M, Topalovic V, Litvinov A, et al. (March 2015). "Mitochondrial DNA perspective of Serbian genetic diversity". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 156 (3): 449–465. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22670. PMID 25418795.

- Davidovic S, Malyarchuk B, Aleksic J, Derenko M, Topalovic V, Litvinov A, et al. (August 2017). "Mitochondrial super-haplogroup U diversity in Serbians". Annals of Human Biology. 44 (5): 408–418. doi:10.1080/03014460.2017.1287954. PMID 28140657. S2CID 4631989.

- Davidovic S, Malyarchuk B, Grzybowski T, Aleksic JM, Derenko M, Litvinov A, et al. (September 2020). "Complete mitogenome data for the Serbian population: the contribution to high-quality forensic databases". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 134 (5): 1581–1590. doi:10.1007/s00414-020-02324-x. PMID 32504149. S2CID 219330450.

- Kačar T, Stamenković G, Blagojević J, Krtinić J, Mijović D, Marjanović D (February 2019). "Y chromosome genetic data defined by 23 short tandem repeats in a Serbian population on the Balkan Peninsula". Annals of Human Biology. 46 (1): 77–83. doi:10.1080/03014460.2019.1584242. PMID 30829546. S2CID 73515853.

- Kovacevic L, Tambets K, Ilumäe AM, Kushniarevich A, Yunusbayev B, Solnik A, et al. (2014). "Standing at the gateway to Europe--the genetic structure of Western balkan populations based on autosomal and haploid markers". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105090. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j5090K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105090. PMC 4141785. PMID 25148043.

- Marjanovic D, Fornarino S, Montagna S, Primorac D, Hadziselimovic R, Vidovic S, et al. (November 2005). "The peopling of modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome haplogroups in the three main ethnic groups". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (Pt 6): 757–763. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00190.x. PMID 16266413. S2CID 36632274.

- Mirabal S, Varljen T, Gayden T, Regueiro M, Vujovic S, Popovic D, et al. (July 2010). "Human Y-chromosome short tandem repeats: a tale of acculturation and migrations as mechanisms for the diffusion of agriculture in the Balkan Peninsula". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (3): 380–390. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21235. PMID 20091845.

- Pericić M, Lauc LB, Klarić IM, Rootsi S, Janićijevic B, Rudan I, et al. (October 2005). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (10): 1964–1975. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

- Regueiro M, Rivera L, Damnjanovic T, Lukovic L, Milasin J, Herrera RJ (April 2012). "High levels of Paleolithic Y-chromosome lineages characterize Serbia". Gene. 498 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.030. PMID 22310393.

- Scorrano G (2017). "The Genetic Landscape of Serbian Populations through Mitochondrial DNA Sequencing and Non-Recombining Region of the Y Chromosome Microsatellites". Collegium Antropologicum. 41 (3): 275–296.

- Šehović E (2018). "A glance of genetic relations in the Balkan populations utilizing network analysis based on in silico assigned Y-DNA haplogroups". Anthropological Review. 81 (3): 252–268. doi:10.2478/anre-2018-0021. S2CID 81826503.

- Todorović I, Vučetić-Dragović A, Marić A (2014). "Непосредни резултати нових мултидисциплинарних етногенетских истраживања Срба и становништва Србије (на примеру Александровачке жупе)". Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta SANU. 62 (1): 245–258. doi:10.2298/GEI1401245T.

- Todorović I (2013). "Нове могућности етногенетских проучавања становништва Србије". Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta SANU. 61 (1): 149–159. doi:10.2298/GEI1301149T. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_8228.

- Todorović I, Vučetić-Dragović A, Marić A (2014). "Компаративни аналитички осврт на најновија генетска истраживања порекла Срба и становништва Србије – етнолошка перспектива" (PDF). Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta SANU. 62 (2): 99–111. doi:10.2298/GEI1402099T.

- Veselinovic IS, Zgonjanin DM, Maletin MP, Stojkovic O, Djurendic-Brenesel M, Vukovic RM, Tasic MM (April 2008). "Allele frequencies and population data for 17 Y-chromosome STR loci in a Serbian population sample from Vojvodina province". Forensic Science International. 176 (2–3): e23–e28. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.04.003. PMID 17482396.

- Zgonjanin D, Alghafri R, Antov M, Stojiljković G, Petković S, Vuković R, Drašković D (November 2017). "Genetic characterization of 27 Y-STR loci with the Yfiler® Plus kit in the population of Serbia". Forensic Science International. Genetics. 31: e48–e49. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2017.07.013. PMID 28789900.

Further reading

- Kushniarevich A, Utevska O, Chuhryaeva M, Agdzhoyan A, Dibirova K, Uktveryte I, et al. (September 2, 2015). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- Kovacevic L, Tambets K, Ilumäe AM, Kushniarevich A, Yunusbayev B, Solnik A, et al. (2014-08-22). "Standing at the gateway to Europe--the genetic structure of Western balkan populations based on autosomal and haploid markers". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105090. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j5090K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105090. PMC 4141785. PMID 25148043.

- "The Genomic History Of Southeastern Europe". bioRxiv 10.1101/135616.

External links

- Serbian DNA Project

- Poreklo - Society of genetic genealogy