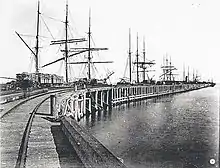

Fremantle Long Jetty was constructed in 1873 to replace the smaller South Jetty which had become too small for the large amounts of vessels entering the colony in Western Australia. The jetty lies in Bather's Bay which has been an occupation site since the Swan River Colony was established in 1829. It was a centre of trade and communications that served Fremantle and Perth until Fremantle Harbour was opened. An increased amount of shipping made it necessary to improve the harbouring facilities by the late 1860s. Long Jetty was built as a less expensive alternative to building a harbour at the mouth of the Swan River due to a lack of funds and technological shortcomings.[1]

In July 1984 the Maritime Archaeology Department of the Western Australian Museum was notified of plans to construct a marina for the 1987 America's Cup that would be close to the remains of the Long Jetty. This prompted an archaeological excavation to ascertain the importance of the site.

History

Construction on the Long Jetty in Fremantle was finished in 1873. This new jetty replaced the original South Jetty that was built in 1857.[2] The Long Jetty was originally known as the Ocean Jetty and the original section was built out of jarrah wood by Mason, Bird and Co., who owned the Canning Saw Mills.[3] The jetty extended south-west from Anglesea Point. From the 1870s to the 1920s the Long Jetty in Bathers Bay was an important maritime centre for the colony of Western Australia.[2] It served as the region's point of access for trade and communication until it was replaced by the opening of Fremantle Harbour in 1897.[2] The original jetty construction was 4.6 metres (15 ft) wide and extended to a length of 230 metres (750 ft).[2] At its original size vessels weighing up to 700 tons could be accommodated, but larger vessels were forced to anchor offshore and have their cargo ferried in on smaller boats.[2]

The main commodities exported from the colony were wool, wheat, and timber.[2] All of these materials were shipped in large vessels that could not be directly loaded from the jetty and required the use of smaller vessels for loading purposes.[2] In December 1887 the jetty was extended to a length of 728 metres (2,387 ft)[2] and the original south-westerly section was widened to 13 metres (42 ft).[3] This would allow six large vessels to be berthed at one time in water that was deeper than provided by the original structure.[2] This addition led to the Ocean Jetty becoming known as the Long Jetty.[2] In 1896 a final extension stretched the jetty an additional 139 metres (457 ft) out into the ocean. This extension was brought about due to the difficulty of lightering. With a total length of 1,004 metres (3,294 ft), it was possible to facilitate eight large ships at once; however, lightering was still required.[2]: 2

Evidence states that the original jetty was too shallow for most ocean-going vessels and lengthened multiple times, but never reached an adequate length. It was always necessary to use lighters to help with the removal of cargo from larger vessels. Of the 600,000 tons of materials that went through the Long Jetty in 1897, over one third of the materials required lightering with smaller vessels. In 1897 the jetty was a total of 1,004 metres (3,294 ft) in length and reached a total depth of only 7 metres (23 ft) at its furthest end.[2]: 2 [4] The two extensions were built by R. O. Law and Mathew Price. In 1887, when the contract was first given to R. O. Law, he was still a minor. R. O. Law was also given the task of demolishing Fremantle Long Jetty after it was considered a hazard to pedestrians.[3]

In the early 1890s, during the Australian gold rushes, Long Jetty reached a period of maximum use whereby ships where constantly coming and going.[2] Even at its full length, it was necessary to use lightering with smaller vessels to bring in many of the shipments.[2] The opening of Fremantle Harbour eliminated the need for lightering and helped to make Long Jetty obsolete as an importing and exporting structure.[2][5]

Disuse

The Fremantle Jetty fell into disuse in the late 1890s due to the creation of the new Fremantle Harbour. Other factors also played a role in the demise of the Fremantle Long Jetty including the weather, geographical issues, and problems with how the port operated. All of these factors and more made the jetty a failure. It is also apparent that the users of this jetty found it and the port of Fremantle to be unsatisfactory. In 1892 in a letter to the owners of the Saranac, Captain D. B. Shaw wrote: "Gentleman, I have been in a good many places in my time, but this is the worst damn hole I ever saw. The stevedores are half drunk all the time and don’t care what they do. The ship has to feed them and give them all the money and tobacco they want or they will make trouble. They are a dirty lot".[2][4]

One week later on 19 November 1892 he wrote again: "I was never so sick of a place in my life, and may the curse of Christ rest on Fremantle and every son of a bitch in it. God damn them all. I remain gentlemen, your obedient servant".[2][4]

In 1904, after a period of abandonment, the jetty was turned into a promenade.[2] In 1906 a hall was built at one end for entertainment purposes.[2] The new incarnation of the jetty was unpopular with the public and by 1910 it was closed off and fell into a state of disrepair.[2] In 1921 it was completely demolished except for its piles that remained in place but were cut down lower to the ocean floor.[2]

Municipal Baths

During the 1890s the Municipal Sea Baths became a popular destination as a public bathing site with several popping up around Perth and the foreshores of Fremantle.[2] The Municipal Sea Baths were located between Long Jetty and South jetty and were demolished in 1917.[2] The Municipal Sea Baths are now covered by a sea-wall associated with the Fishing Boat Harbour.[2]

Archaeological excavations

The jetty received renewed interest with antique bottle collectors in the late 1960s as the ocean floor surrounding the jetty was covered with soda and beer bottles. Bottle collectors had frequently visited the site since its use was discontinued, but it was noticed that storms would reveal new materials from under the sea bed.[6] The remains of the site were frequently visited by Scuba divers for recreation or bottle collecting. The site is pockmarked by holes dug by these collectors. These collectors had removed almost everything that is deemed attractive material leaving only broken pieces scattered across the site.[2]

In 1984 plans for a new marina that would facilitate the 1987 America's Cup threatened to bury large sections of what remained of Long Jetty.[6] After many years of disuse, the jetty had been reduced to a row of piles that were barely visible above water except for one which remained exposed, 3 metres (9.8 ft) out of the water. The Western Australian Maritime Museum was only given a four-week notice to record the site before construction on the new marina would commence. This was because construction plans for the new marina involved covering a large portion of the old jetty.[4]

Archaeological investigations were headed by Michael McCarthy from the Department of Maritime Archaeology at the Western Australian Maritime Museum. The excavation was essentially a case of salvage archaeology; therefore, the museum instigated immediate assessment of the impact that a marina would have on the old jetty. The Aims for the excavation were described as 'mapping the remaining jetty structure to ascertain the spread of material and to gauge the extent to which it could later be covered or disturbed by the [marina] development.[2] Archaeological work included plotting the jetty piles with the use of triangulation and photography in order to create a map of the site.

McCarthy was allocated a budget of $2,000 to conduct the excavations on the Long Jetty.[2] Due to the low funding available to McCarthy, volunteers from the Maritime Archaeological Association of Western Australia (MAAWA), a volunteer organisation intent on furthering protection and education about maritime sites, were used due to their experience with swim-line searches and archival research. There were also other volunteers who came from a local high school who were on work experience. These MAAWA divers were responsible for conducting swim-line searches of the sea floor for any artefacts and high concentrations of artefacts were marked by buoys which would require further investigation from the Museum staff.[2] $1,315 of the $2,000 was spent on the excavation phase.[2]

Because of time constraints, McCarthy implemented the use of airlift and propeller wash excavation methods to shift sediment.[4] Seventy test excavation holes were created to excavate the site. Most of the artifacts found during the excavations were made of glass originating from Australia or Great Britain, but some of the glass materials were from the United States of America. All of the bottles recovered from the excavation were found to be from a date range of 1840 to 1920. Alcohol and soft drink bottles were the most common types of bottles discovered, but pickle, sauce, and medicine containers were also frequently excavated on the site.[4] The most common type of bottle found was a champagne style bottle which is similar to those used today.[6]

Artefacts

A large number of artifacts were recovered from the site during the excavations. Most of the artefacts were covered by a protective layer of sediment up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) deep.[2] Artefacts recovered included buttons, buckles, fasteners, rings, toys, pipes, munitions, shoes, fishing equipment, and other materials.[4] A sample of artefacts were catalogued and conserved for public display. Seeing as the site was so close to the Maritime Museum, recovered artefacts were placed in tubs of fresh water to start the desalination process, while fragile artefacts were wrapped in soft nylon mesh to protect them from damage during the short transit to the Museum.[2]

Exhibition

Soon after the excavation was completed, the Western Australian Maritime Museum opened an exhibition pertaining to the Long Jetty in an effort to educate the public about its history. The publicity that was generated through the excavations, public education, and press articles were sufficient enough to change the designs of the marina wall so that it would miss the jetty piles, thereby protecting the remains of the Long Jetty from destruction.[4] However, a small section of the jetty would still be affected.[2]

2000s

The jetty is a tangible link to the past and represents a valuable historic resource which can help to look at the economic and social evolution of the city of Fremantle. The site is also important due to its link with the immigration of people into Western Australia.[2] Joan Campbell created illustrated ceramic plaques detailing the work of the museum as well as the history of the Fremantle Long Jetty that were placed at the beach end of the structure. The area is now used for public recreation activities.[4] Remains of the Long Jetty are still visible with approximately 30 of the original piles protruding from the surface of the water.[2]

Legislation

In 1988 the sea bed surrounding the section of the jetty that was built before 1900 was designated a historic site. This was implemented as a requirement under the Maritime Archaeology Act of 1973. The Act required that all areas of the sea-bed underneath jetties in Western Australia be designated as maritime archaeological sites if the jetty was used before 1900. This meant that the Act encapsulated basically all of the area where the Long Jetty stood.[4]

References

- ↑ Garratt, Dena (1990). "The Long Jetty: A Case Study in Salvage Archaeology" (PDF). Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Maritime Museum, Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Garratt, Dena (1994). "The Long Jetty Excavation 14 July to 20 August 1984: A Report on the Long Jetty Excavation" (PDF). Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Maritime Museum, Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 Hitchcock, J. K.; Stevens, J. W. B. (1929). The History of Fremantle: The Front Gate of Australia, 1829 – 1929. Fremantle: Fremantle City Council. OCLC 32586494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 McCarthy, Michael (2002). "The archaeology of the Jetty: an examination of jetty excavations and 'port-related structure' studies in Western Australia since 1984". Journal of the Australasian Institute for Maritime Archaeology. 26: 7–18. ISSN 1447-0276.

- ↑ "Departed Glory: The Old Long Jetty, Fremantle". The West Australian. Vol. XLV, no. 8, 320. Western Australia. 16 February 1929. p. 6. Retrieved 3 July 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 3 McCarthy, M. (1987). "The Ocean Jetty: The Colonial Beer Garden?". Australian Archaeology. 24 (1): 32–35. doi:10.1080/03122417.1987.12093100.

![]() Media related to Fremantle Long Jetty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fremantle Long Jetty at Wikimedia Commons