The Constitution provides for freedom of religion; however the law cites the “exceptional importance” of Orthodox Christianity.[1]

In 2022, the country was scored 3 out of 4 for religious freedom.[2]

Overview

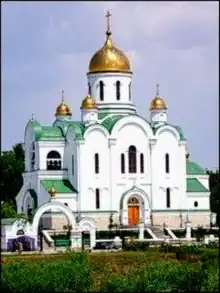

According to the Moldova's 2014 census, 90% of the population belonged to Orthodox Christian Churches; 81% to the Moldovan Orthodox Church and 9% to the Bessarabian Orthodox Church. Nearly 7% of the population had no religious affiliation. Other religious groups include Baptists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Pentecostals, Jews, Seventh-day Adventists, evangelical Christians, Catholics, Lutherans, Muslims, Baha’is, Molokans, Messianic Jews, Presbyterians, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Salvation Army, the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (Unification Church), Falun Gong, and the International Society of Krishna Consciousness.[1]

In the Transnistria region, the local authorities estimate that 80% of the population belonged to the Moldovan Orthodox Church in 2022.

There is no state religion in Moldova; however, in the early 2000s, the Metropolis of Chişinău and Moldova receives some favoured treatment from the Government. The Metropolitan of Chişinău and Moldova has a diplomatic passport. Other high-ranking Orthodox Church officials also reportedly have diplomatic passports issued by the Government.[3] For this reason, scholars claimed that an approach exclusively centred on the religious freedom juridical frame would appear inaccurate.[4]

The law does not require religious groups to register, and members of unregistered groups may worship freely; however religious groups must be registered if they wish to build houses of worship, own land for cemeteries or other property, publish or import religious literature, open bank accounts, employ staff or claim exemption to land taxes.[1] Only missionaries working with registered groups can apply for a temporary residence visa, otherwise they are eligible for a tourist visa.

In 1999, amendments to the Law on Religions legalizing proselytizing went into effect.[3] However, the law explicitly forbids "abusive proselytizing", which is defined as an attempt to influence an individual's religious faith through coercion; the authorities in Transnistria have banned proselytizing in private homes.[1]

In 2002, a new draft Law on Religions, which contained numerous contentious provisions, was circulated. The draft law originally contained numerous restrictive measures. The draft law was revised in 2004, and it appeared that many of the restrictive articles have been deleted.[3]

In February 2003, a new Law on Combating Extremism was passed by Parliament and took effect in March 2003. Critics of the law raised concerns that the law could be used to abuse opposition organizations, which could include religious organizations or individuals who may support or have political ties to certain parties. But in practice this law had never been used against any religious organizations.[3]

A new Criminal Code, adopted by Parliament in April 2002 and in effect since June 2003, includes an article which permits punishment for "preaching religious beliefs or fulfillment of religious rituals, which cause harm to the health of citizens, or other harm to their persons or rights, or instigate citizens not to participate in public life or of the fulfillment of their obligations as citizens." Drafters allegedly copied the passage almost word-for-word from the previous code, which was passed in 1961 when the country was part of the Soviet Union.[3]

Article 200 of the Administrative Offenses Code, which was adopted in 1985, prohibits any religious activities of registered or unregistered religions that violate current legislation. The article also allows for the expulsion of foreign citizens who engage in religious activities without the consent of authorities. In the early 2000s, the Spiritual Organization of Muslims has reported being fined under this provision of law for holding its religious services in a location registered to a charitable organization. The Government charged that their activities are not in line with the stated activities and purposes of the charitable organization.[3]

The law states that religion classes in state schools are optional. They are offered in primary schools and pupils may submit a written request to a school’s administration to join a religion class.[1]

In the early 2000s, there were two public schools and a kindergarten are open only to Jewish students, and a kindergarten in Chişinău had a special "Jewish group". These schools received the same funding as other state schools and were supplemented by financial support from the community. However, Jewish students are not restricted to these schools. There were no comparable schools for other religious faiths and no reports of such schools for other religious faiths. Agudath Israel operated a private boys' yeshiva and a girls' yeshiva, both licensed by the Ministry of Education. The total enrollment of both schools was fewer than 100 students. Total enrollment for all Jewish related schools, including those operated by Agudath Israel and public schools, was approximately 300.[3]

Restrictions on Religious Freedom

2001 Orthodox dispute

In the early 2000s, there was an ongoing succession dispute between the two autonomous Eastern Orthodox churches (Moldovan Orthodox Church belonging to the Russian Orthodox Church, and Metropolis of Bessarabia belonging to the Romanian Orthodox Church). from an ecclesiastical point of view, this is an administrative only issue (subject to canon laws), not a theological one, as the two belonged respectively to two autocephalous Churches (of Russia and of Romania), which are within the Eastern Orthodox communion.

Thus, in 2001, the Government declared the Moldovan Orthodox Church the successor of the pre-World War II Romanian Orthodox Church for purposes of all property ownership. The Metropolis of Bessarabia was reactivated in 1992 (after Moldova declared independence in 1991) when a number of priests broke away from the Moldovan Orthodox Church, and was only officially recognized in 2002, after years of being denied recognition.[3] The dispute was brought in front of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) which ruled in 2004 in favor of the Metropolis of Bessarabia as the "spiritual, canonical, historical successor of the Metropolitan See of Bessarabia which functioned till 1944, including".[5] In February 2004, the Supreme Court repealed the Government's 2001 decision. In April 2004, in response to an appeal submitted by the Government, the Supreme Court rescinded its February ruling, making the Moldovan Orthodox Church once again the legal successor to the pre-World War II Romanian Orthodox Church. The Metropolis of Bessarabia, which regards itself as the legal and canonical successor to the pre-World War II Romanian Orthodox Church, being endorsed by the ECHR, does not accept this decision. The registration issue has political as well as religious overtones, since it raises the question of whether the Orthodox Church should be oriented toward the Moscow Patriarchate or the Bucharest Patriarchate.[3]

In May 2002, after a long series of registration denials and legal appeals, the Supreme Court of Justice ruled that the Government must register the Church of the True Orthodox-Moldova, a branch of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, which is based in the United States. The State Service on Religious Issues failed to implement the decision in the stipulated 30 days and subsequently asked the Court for a 2-week extension to register the church. But after 3 weeks, instead of registering the church, the Service filed an extraordinary appeal with the Court of Appeals. The Court reviewed the appeal and declared that the Service was not allowed to file the appeal, since the case was made against the Government, not the Service. Within a couple of weeks another appeal from the Prime Minister was filed. In early 2004, the appeal was sent to the Supreme Court and was under examination at the end of the period covered by this report. The Church had submitted applications for registration in 1997, 1998, and 2000; the Government rejected these applications on various grounds.[3]

Judaism

In 2021, a new law was created making Holocaust denial and insulting the memory of the Holocaust criminal offenses.[1] Later that year, the government rejected an application for registration of a synagogue in Orhei; however, by the end of the year, the government had approved the construction of a Holocaust memorial.

Muslims

In 2022, Islamic League leaders said that societal acceptance of Muslims had improved.[1]

Pagan

The Kishinev community a "Patrimonial Ring" ("Родовое Кольцо") unites adherents of Slavic vernacular religion.

Others

Several religious minorities have reported difficulties in planning permission for building houses of worship.[1]

Situation in Transnistria

In the early 2000s, the Transnistrian authorities have developed a new textbook that was to be used at all school levels, which reportedly contained negative and defamatory information regarding the Jehovah's Witnesses.[3]

In 2021, Jehovah’s Witnesses were unable to reregister as a religious organization and reported two active law cases regarding forced alternative civilian service in defense-related institutions, which was contrary to their beliefs.

The Muslim community remained unable to secure a site for a mosque in Transnistria after receiving a permit for one in 2019.

Abuses of Religious Freedom

The Spiritual Organization of Muslims has reported regular harassment by the police. Members say the police often show up at their Friday prayers, which are held at a local Islamic organization's offices, checking participants' documents and taking pictures. On March 5, the police raided their meeting place after Friday prayers, detaining several members and subsequently deporting three Syrian citizens for not having proper legal residence documents. The authorities claimed the religious services were illegal because the organization is not registered, and the place they were meeting was registered to a charity and was not being used for its stated purpose.[3]

In several cases, members of Jehovah's Witnesses reported being detained and fined for preaching their religion. In the village of Cruzesti, the mayor and residents of the village physically blocked members of Jehovah's Witnesses from the public cemetery for not respecting the customs of the Orthodox religion.[3]

The Jehovah's Witnesses in Transnistria have reported several incidents of administrative fines and unjust arrests of their members. In all reported cases, the charges have been dropped in appeals at the level of the Supreme Court.[3]

Societal Attitudes

In 2021, leaders of minority religious groups reported a general improvement in the authorities’ attitude towards them, improved societal acceptance and an easing of the preferential treatment state institutions traditionally provided to the Moldovan Orthodox Church.[1]

In 2004, more than 70 tombstones were desecrated in the Jewish cemetery in Tiraspol. Swastikas and other Nazi symbols were painted on monuments, and many tombstones were damaged beyond repair. On May 4, unknown persons attempted to set the Tiraspol synagogue on fire by throwing a Molotov cocktail onto the premises near a local gas supply. The attack failed when passers-by extinguished the fire. Transnistrian authorities believe the attacks were propagated by the same people and claim they are investigating the incidents.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 US State Dept 2021 report

- ↑ Freedom House website, retrieved 2023-08-08

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

This article incorporates public domain material from Moldova: International Religious Freedom Report 2004. United States Department of State. See also: Religie și Societate în Republica Moldova. Studiu de caz: Congresul Mondial al Familiilor (www.platzforma.com).

This article incorporates public domain material from Moldova: International Religious Freedom Report 2004. United States Department of State. See also: Religie și Societate în Republica Moldova. Studiu de caz: Congresul Mondial al Familiilor (www.platzforma.com). - ↑ A Context-Grounded Approach to Religious Freedom: The Case of Orthodoxy in the Moldovan Republic - D. Carnevale https://www.mdpi.com/458996

- ↑ cf. press release: A legitimate act for defending the Romanian identity - Explanations concerning the juridical recognition of the Metropolitan See of Bessarabia and of the suffragan eparchies Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, Romanian Patriarchy, 21 February 2008. — "Archived copy" (PDF) (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) — "Stiri" (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 2008-02-26. Retrieved 2008-04-21. — "Archived copy" (PDF) (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-04-21.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)