Frank Curzon (17 September 1868 – 2 July 1927) was an English actor who became an important theatre manager, leasing the Royal Strand Theatre, Avenue Theatre, Criterion Theatre, Comedy Theatre, Prince of Wales Theatre and Wyndham's Theatre, among others.

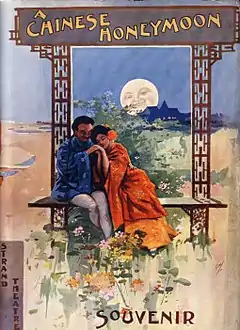

Curzon produced some of the most successful Edwardian musical comedies, including A Chinese Honeymoon (1903) and Miss Hook of Holland (1907; one of several successes starring his wife, Isabel Jay), and he later produced several plays starring Ivor Novello. Curzon was involved in a number of legal disputes, the most celebrated of which involved an audience member who refused to remove her hat. When Curzon prevented her from returning to her seat, she charged him with assault. Curzon won.

Later in life, Curzon became a very successful racehorse breeder, and in 1927 his horse Call Boy won The Derby.

Biography

Curzon was born in Wavertree, Liverpool, England, the son of W. Clarke Deeley of Curzon Park, Chester, and his wife Elizabeth, née Mallaby.[1] His real name, under which he appeared in several legal cases, was Francis Arthur Deeley.[2] His brother was Sir Harry Mallaby-Deeley.[3] He took the name Curzon by deed poll in 1896. His first wife was the Irish-born actress Caroline Julia Cronyn (1867–1955), whom he married in 1893 in Dublin, Ireland, and who divorced him in 1909. They had one child, Suzanne, born in 1906.[4] His second wife was the actress and singer Isabel Jay, one of his stars, whom he married on 28 July 1910.

Theatre career

After working briefly in his father's oil company, Curzon went on the stage, touring with Frank Benson's company.[1] He made his London debut at the age of 24 in a play called Queer Street, at Terry's Theatre. In 1899, he and Charles Hawtrey leased the Avenue Theatre, where they had a series of successes.[1] After this, Curzon concentrated on his managerial career, though he made a brief return to acting in 1923 in The Inevitable, a play written by and starring his wife, Isabel Jay.[1]

Curzon was a founder member of the Society of West End Theatre Managers, along with Helen Carte, George Edwardes, Arthur Bourchier and sixteen others.[5] At one point in his theatre career he had nine London theatres under his management.[6] Some of his biggest successes as a producer and theatre manager included Monsieur Beaucaire (1902), A Chinese Honeymoon (1903), Sergeant Brue (1904), The White Chrysanthemum (1905), The Girl Behind the Counter (1906), See-See (1906), Mr. Hopkinson (1906), Miss Hook of Holland (1907), King of Cadonia (1908), My Mimosa Maid (1908), Dear Little Denmark (1909), and The Balkan Princess (1910; co-written by Curzon). A rare failure was The Three Kisses (1907). Many of Curzon's shows were filled with spectacle, using exotic sets, elaborate costumes and beautiful chorus girls. He also produced a number of plays starring Ivor Novello, including Enter Kiki (1923), The Firebrand (1926) and Downhill (1926).

One of Curzon's few miscues was to turn down the opportunity to produce The Maid of the Mountains (1916), which became a huge success.[7]

Court cases

Curzon was involved in several legal cases. In 1894 his financial failure was the subject of a successful court action against him.[2] In 1901 he and Charles Hawtrey were jointly sued for slander by a disgruntled actor; they won the case. In 1910 Curzon appeared in court in two separate cases, a dispute with the lessor of his theatre over tax liabilities[8] and in another slander case, this time as plaintiff, against an acquaintance who falsely alleged that Curzon left his first wife penniless after their divorce in 1909. Curzon, who in fact allowed his ex-wife £25 a week (equivalent to about £2,000 in 2007 values),[9] won the case but was awarded only nominal damages.[10]

Also in 1910 was the most famous legal case in which Curzon was involved. The press called it "The Matinée Hat Incident." He was charged with assault by a woman named Blanche Eardley. She had refused to remove her hat despite vociferous protests from a male spectator, and Curzon had physically prevented her from re-entering the auditorium after the interval.[11] According to Mrs Eardley, her refusal was on a point of feminist principle. The magistrate ruled in favour of Curzon and dismissed the case amid applause from the gallery. As the actress Eva Moore noted, "everyone heard of the fight to the death between Frank Curzon and the matinée hat."[12]

Racing

Later in life, Curzon bred racehorses, with successes at courses including Aintree, Warwick and Epsom.[13][14][15] He commanded high prices for his best horses, selling one in 1917 for 1,500 guineas.[16] The pinnacle of his racing career was in 1927, when his horse Call Boy won the Derby. Curzon made his last public appearance at Epsom, against medical advice, to see Call Boy win. He was personally congratulated by George V.[1] By the time of his death, he was as noted for his racing activities as for his theatrical career.[1]

After a long illness, Curzon died, aged 59, at his country home in Newmarket, Suffolk, England, near the famous Newmarket Racecourse. He was buried at Newmarket.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Times Obituary, 4 July 1927, p. 16

- 1 2 "Theatrical Failure". The Times. London. 9 May 1894. p. 4. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ The Times obituary of Sir Harry, 6 February 1937, p. 14

- ↑ "Probate, Divorce, and Admiralty Division". The Times. London. 23 April 1909. p. 3. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Society of West-End Theatre Managers". The Times. London. 24 April 1908. p. 17. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Death of Mr. Frank Curzon". The Observer. London. 3 July 1927. p. 19. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Frederick Lonsdale biography at the British Musical Theatre pages of The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

- ↑ "High Court of Justice". The Times. London. 26 April 1910. p. 4. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Measuring Worth historical currency equivalence calculator

- ↑ "A Slander Action Settled". The Times. London. 27 May 1910. p. 3. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Police Courts". The Times. London. 16 April 1910. p. 11. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Barstow, Susan Torrey. "Hedda Is All of Us: Late-Victorian Women at the Matinée", Victorian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 3 (Spring, 2001), pp. 387–411, Indiana University Press.

- ↑ "Prospects at Kempton Park". The Times. London. 5 April 1915. p. 10. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Racing at Warwick". The Times. London. 8 April 1915. p. 12. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The City and Suburban To-Day". The Times. London. 21 April 1915. p. 13. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Bloodstock Sales". The Times. London. 5 December 1917. p. 5. Retrieved 8 November 2023 – via Newspapers.com.